1. Context

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are complications that may affect the incision site or deep tissues, occurring up to 30 days post-surgery or up to a year later in patients with implants (1). The SSIs rank as the second most common nosocomial infection, accounting for 15 - 30% of all such infections (2, 3). Among surgical patients, SSIs are the most prevalent, comprising approximately 38% of all surgical infections. These infections are either confined to superficial and deep tissues or occur in involved organs or spaces, in two-thirds and one-third of cases, respectively (3-5).

The causal pathogens in most SSIs are derived from the patient's natural flora, with Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, enterococci, and Escherichia coli being the most common microorganisms (1). Beyond increased morbidity and occasional mortality, SSIs lead to hospital readmissions, increased medical costs, and sometimes necessitate repeat surgeries (6). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are 500,000 cases of SSIs annually in the United States, with an average hospital stay of 7.5 days and an annual cost of approximately 130 - 145$ million (6). An estimated 188,000 - 398,000 cases of SSIs are reported annually in the United States (7).

The prevalence of SSIs is higher in orthopedic surgeries compared to other surgical procedures (8). Approximately 28% of nosocomial infections in orthopedic departments are due to SSIs (9), which can extend hospital stays to 28 days and increase treatment costs by more than 188%. Patients with orthopedic SSIs experience greater physical limitations and a reduced quality of life (10). While success after orthopedic surgery depends on several factors, complications such as periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) remain a major concern. The PJI significantly contributes to inefficiency and the need for implant reuse (11). In the USA, hospitals were projected to spend over $1.62 billion on re-surgeries for orthopedic prosthesis infections in 2021 (12). Infections are the third most frequent reason for knee surgery (11).

The SSIs account for 13 - 88% of simple tibia fractures, 2 - 17% of femoral fractures, 2 - 10% of patellar fractures, and 3 - 45% of varied proximal tibia fractures following orthopedic procedures (13). In Europe, the prevalence of SSIs in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) surgeries ranges from 0.5% in France to 2.2% in the Netherlands (14-18), and in the United States, it is reported at 0.9 - 2.3% (18). Given the increasing prevalence of total joint arthroplasty surgeries and the status of SSIs as the most common infection in surgical patients, maintaining hygiene and sterility during and after surgery to mitigate the risk of SSIs should be a priority for surgical teams.

Preventing and controlling SSIs in TKA surgeries is essential as it reduces mortality, rehospitalization, shortens recovery periods, and decreases costs for both patients and the healthcare system. To effectively prevent such complications, accurate information about these infections is crucial.

2. Objectives

This review and meta-analysis aim to assess the prevalence of SSIs in TKA surgeries among surgical patients.

3. Evidence Acquisition

3.1. Study Aim and Quality Assessment

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of SSIs in TKA surgeries among surgical patients through a systematic review and meta-analysis, adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.

3.2. Search Strategy

The researchers of the present study explored three international databases—PubMed, Scopus, and Embase—in November 2024. The keywords selected for the database searches included: ["Surgical Wound," "Surgical site," "Postoperative wound," "SSIs"] AND ["Infect*," "Infestation"] AND ["Knee surgery," "Knee replacement," "Knee arthroplasty"] AND ["prevalence," "frequency," "incidence," "epidemiology"]. The collected data were entered into EndNote X8 software, and duplicate articles were automatically removed. Subsequently, the articles were independently evaluated by two researchers.

3.3. Study Selection

To screen the eligibility of the articles, a primary screening was conducted based on the title and abstract by two independent researchers. A secondary screening was then performed on the remaining articles from the first step by reading the full text. Conflicts at each of these steps were resolved by a third researcher. All human studies that assessed SSIs in TKA surgeries were included in the study, while animal studies and unrelated articles were excluded.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Cochran's test (with a significance level of less than 0.1) and the I2 statistic (with a significance level greater than 50%) were performed to assess heterogeneity between the studies. In addition to Cochran's test and the I2 statistic, subgroup analysis and meta-regression were also employed to examine study heterogeneity. In cases of heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used with the inverse-variance method, whereas a fixed-effects model was applied in the absence of heterogeneity. Given the significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 99.3%, P < 0.001), the random-effects model was utilized. All analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software, version 12.

4. Results

4.1. Description of Searching for Articles

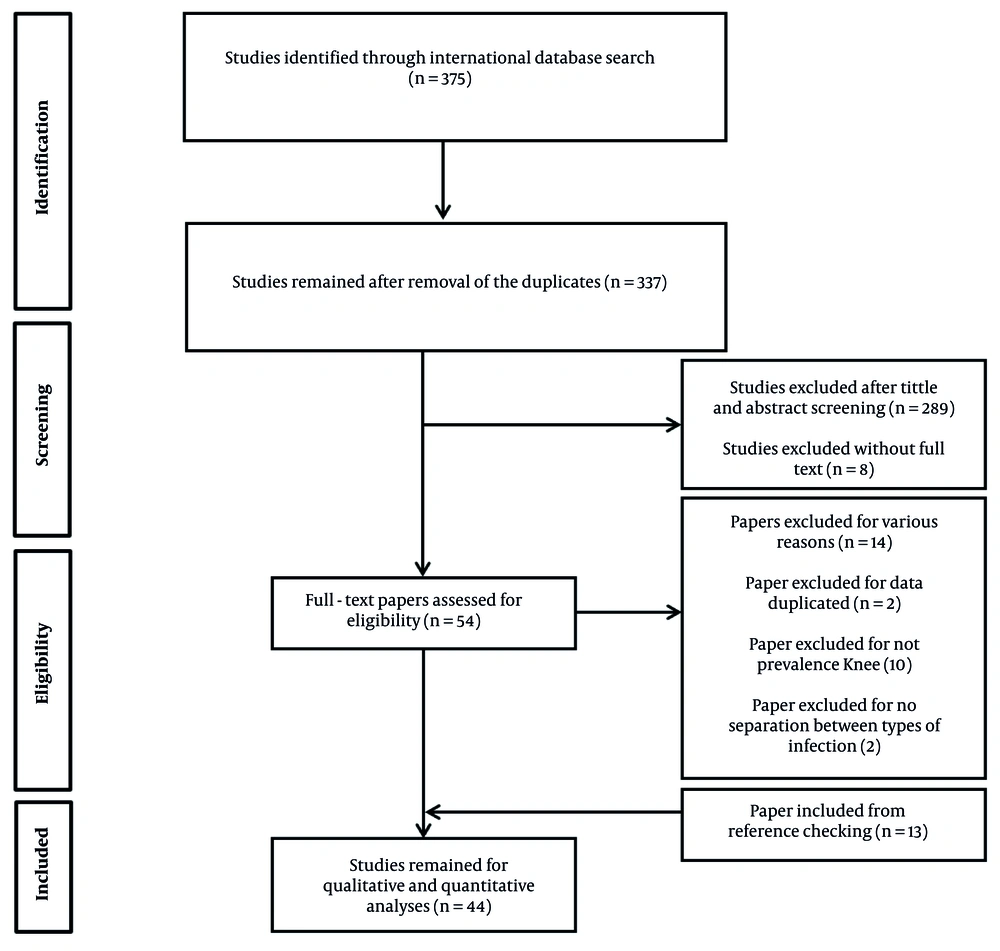

A total of 375 articles were identified after searching all specified databases. Fifty-four papers proceeded to the next step, where the full text of the articles was assessed. After eliminating duplicate and irrelevant studies during the title and abstract screening stage, 31 articles were included in the final analysis. Additionally, by reviewing the references of the selected articles, 13 studies were added, resulting in a total of 44 studies being reviewed (Figure 1).

4.2. Description of the Included Studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the evaluated studies. Among the selected studies, fifteen were conducted in the United States (19-33), five in Canada (34-38), three in Spain (39-41), and two each in Brazil (42, 43), Finland (44, 45), Germany (15, 46), Korea (47, 48), and Poland (49, 50). Additionally, one study was conducted in each of the following countries: Australia (51), the United Kingdom (52), France (2, 53), India (54), the Netherlands (55), Israel (56), Italy (57), Japan (58), Scotland (59), and Taiwan (60). In one study, the country of origin was not specified (37). The highest prevalence of SSIs was reported in Brazil, at approximately 25%, while the lowest prevalence was observed in the United States, at 0.22%.

| First Authors (Year) | Country | Sample Size | Gender | Mean Age | Tools | Prevalence (%) | Quality | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson (2008) | USA | 9658 | - | - | Electronic data | 0.76 | Good | (19) |

| Mannien (2008) | Netherland | 15176 | Both | 72 | Questionnaire | 1.2 | Good | (20) |

| Miletic (2014) | USA | 76289 | Both | 64.3 | Observation | 0.87 | Good | (21) |

| Miner (2007) | USA | 8,288 | - | - | Observation | 0.34 | Satisfactory | (22) |

| Von Dolinger (2010) | Brazil | 12 | - | - | Observation | 25 | Good | (23) |

| Perdiz (2016) | Brazil | 102 | - | - | Observation | 12.74 | Good | (24) |

| Reilly (2006) | Scotland | 1298 | Both | - | Observation | 1.46 | Good | (25) |

| Rennert-May (2016) | Canada | 160 | Both | 66.7 | Electronic review | 1.26 | Good | (26) |

| Rennert-May (2018) | Canada | 10736 | - | - | Observation | 1.05 | Good | (27) |

| Singh (2015) | India | 3280 | - | - | Check list | 1.7 | Good | (28) |

| Song (2011) | Korea | 1323 | male | - | Check list | 1.06 | Good | (29) |

| Song (2012) | Korea | 3426 | Both | 66 | Check list | 2.82 | Good | (30) |

| Rusk (2016) | Canada | 7135 | - | - | Check list | 1.1 | Good | (31) |

| Calderwood (2012) | USA | 724 | Both | 65 | Observation | 1 | Good | (32) |

| Curtis (2004) | Australia | 122 | - | - | Observation | 1.68 | Good | (33) |

| Arduino (2015) | USA | 8446 | - | 60 | Electronic data | 0.52 | Good | (34) |

| Baier (2019) | Germany | 2439 | Both | 69 | Electronic data | 3.4 | Good | (35) |

| Castella (2011) | Italy | 645 | Both | 70.8 | Electronic data | 1.86 | Good | (36) |

| Debarge (2007) | 923 | Both | 71 | Electronic data | 2.1 | Good | (37) | |

| Dicks (2015) | USA | 42187 | - | 67 | Electronic data | 1.03 | Good | (38) |

| Dyck (2019) | Canada | 7737 | - | 67 | - | 1.38 | Good | (39) |

| Grammatico-Guillon (2015) | France | 11045 | - | 72 | Electronic data | 2 | Good | (40) |

| Guirro (2015) | Spain | 3000 | Both | 70 | Electronic data | 1.5 | Good | (41) |

| Huenger (2005) | Germany | 248 | Both | 68.1 | Electronic data | 0.4 | Good | (15) |

| Houtari (2006) | Finland | 3706 | - | 71 | Electronic data | 2.3 | Good | (42) |

| Inacio (2011) | USA | 27539 | - | - | Electronic data | 1.06 | Satisfactory | (43) |

| Jean (2012) | Spain | 2088 | Both | 71 | Electronic data | 2.1 | Good | (44) |

| Jenks (2014) | England | 970 | - | - | Electronic data | 3.2 | Good | (45) |

| Kadota (2016) | Japan | 196 | - | 64 | Electronic data | 2.04 | Good | (46) |

| Kołpa (2020) | Poland | 847 | - | - | - | 1.53 | Good | (47) |

| Lewallen (2014) | USA | 11072 | Both | 67.5 | Electronic data | 1.94 | Good | (48) |

| Lopez-Contreras (2012) | Spain | 16781 | - | 68 | - | 3.3 | Good | (49) |

| Babkin (2007) | Israel | 180 | Both | 72.4 | Electronic data | 5.6 | Good | (50) |

| Jamsen (2010) | Finland | 2647 | Both | 70 | Electronic data | 2.9 | Good | (51) |

| Kurtz (2010) | USA | 69633 | - | - | Electronic data | 2 | Good | (52) |

| Peersman (2001) | USA | 6489 | - | - | - | 1.74 | Good | (53) |

| Poultsides (2013) | USA | 784335 | Both | 66.36 | Electronic data | 0.31 | Good | (2) |

| Pugely (2015) | USA | 16291 | Both | 67.3 | Electronic data | 1.22 | Good | (54) |

| Pulido (2008) | USA | 4185 | - | 65 | Electronic data | 1.1 | Good | (55) |

| Wu (2016) | Taiwan | 3152 | Both | 69.7 | Electronic data | 1.52 | Good | (56) |

| Yokoe (2013) | USA | 121640 | Both | 67.7 | Electronic data | 2.02 | Good | (57) |

| Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (2020) | Canada | 3904 | Both | 67 | Check list | 8.73 | Good | (58) |

| Slowik (2020) | Poland | 584 | Both | 70 | Check list | 1.9 | Good | (59) |

| Zastrow (2020) | USA | 862918 | - | - | Check list | 0.22 | Good | (60) |

4.3. Evaluation of the Articles Quality

The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist was utilized to evaluate and regulate the quality of the content. The objectives of this tool are to assess the methodological quality of research and to identify and prevent errors in study design, execution, and data analysis (Table 1).

4.4. Results from Meta-Analysis of the Studies

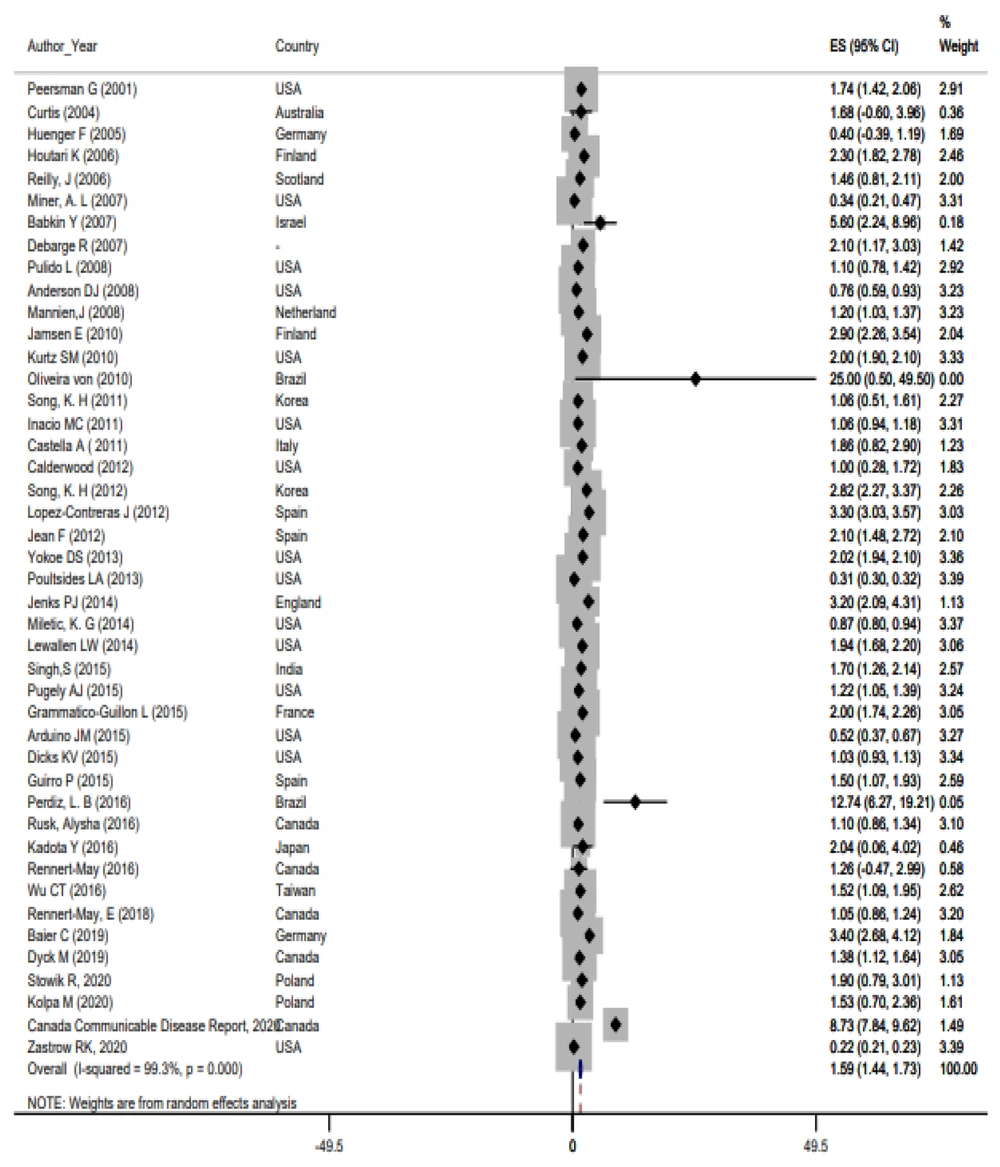

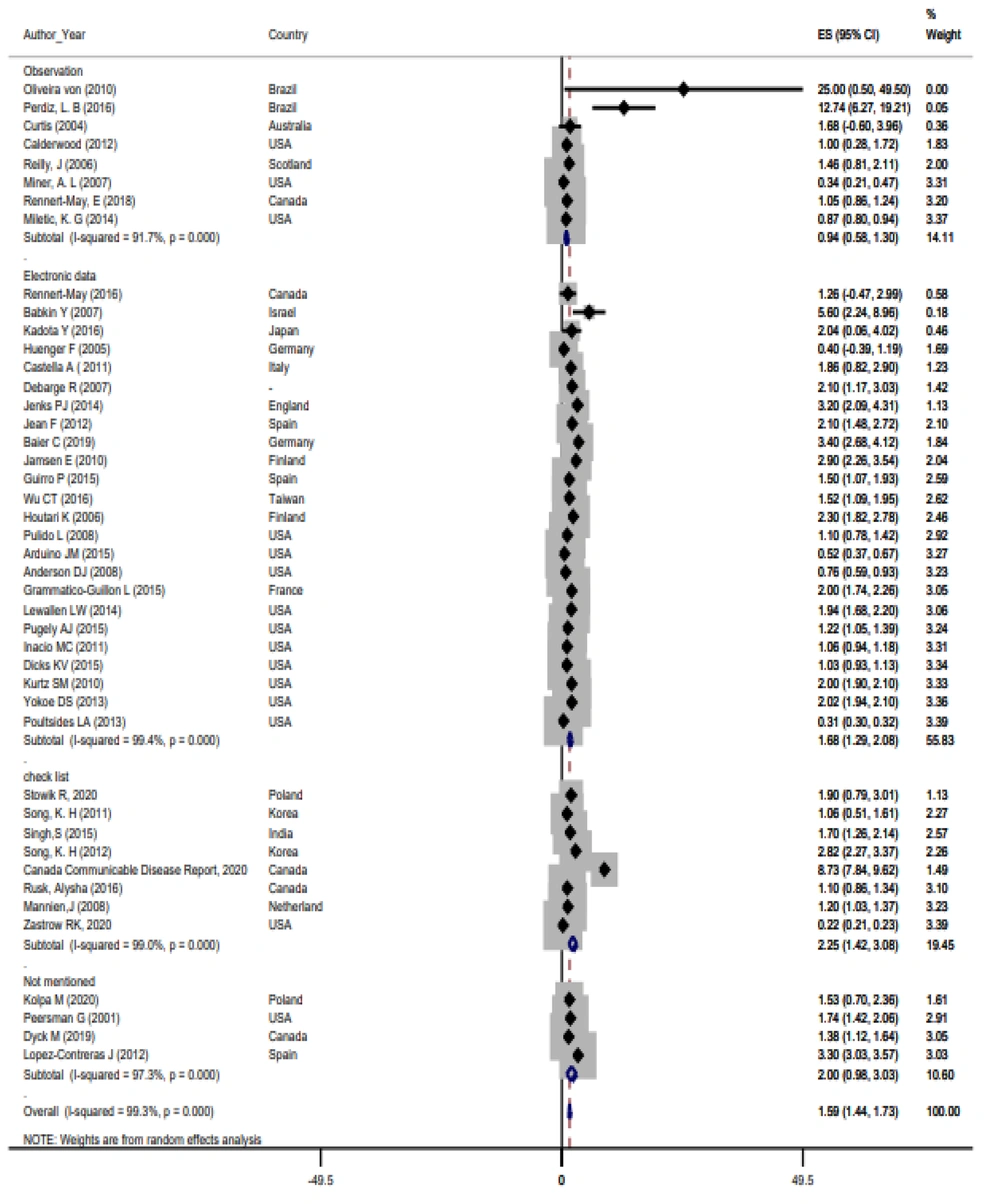

Based on the random-effects model, the prevalence of SSIs was 1.59% with a 95% confidence interval of 1.44 - 1.73. The results related to the forest plot studies are shown in Figure 2. The findings also indicated heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 99.3%, χ2 = 5940.64, τ2 = 0.1604, P < 0.001). Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis were conducted to determine the causes of heterogeneity in the study findings. According to the subgroup analysis, although the prevalence rate varied depending on the data collection instruments, heterogeneity persisted across all subgroups (Figure 3).

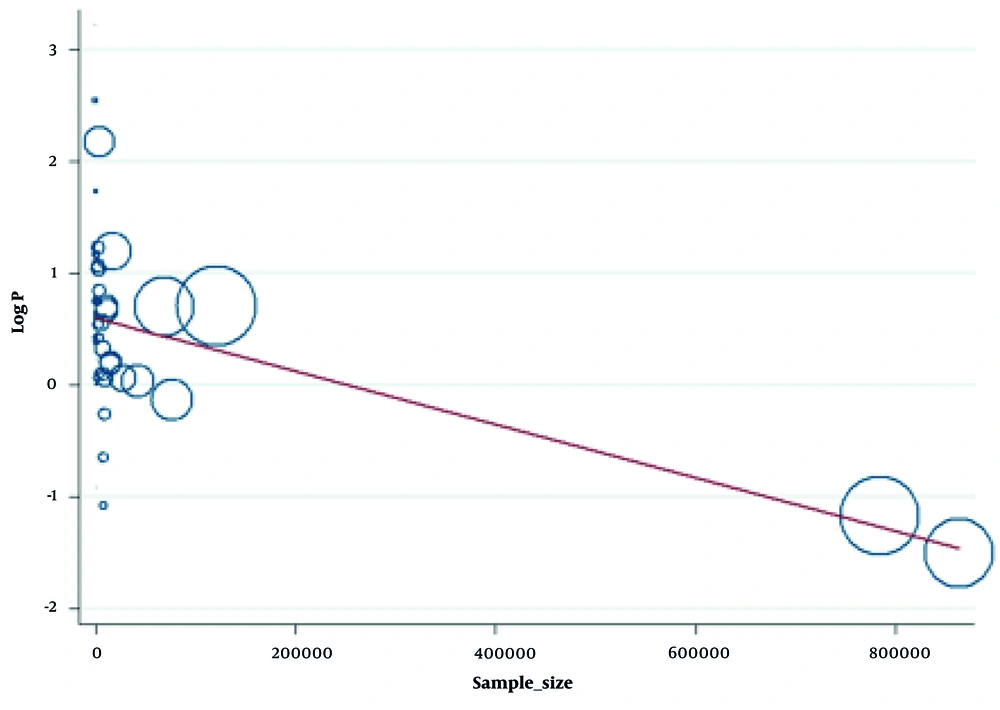

To further explain the heterogeneity, meta-regression was performed on the sample size of the studies. The meta-regression findings indicated that sample size was a potential cause of heterogeneity, accounting for approximately one-third of it (R2 = 32.23%, P < 0.001). Therefore, with increasing sample sizes, the reported prevalence of infection was lower (Figure 4).

5. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the prevalence of SSIs in TKA surgeries. After reviewing 44 studies, the results indicated that the prevalence of SSIs was 1.59% in patients undergoing TKA surgeries, which is considered low and acceptable. The SSIs following TKAs are often a significant issue for the healthcare system, resulting in substantial expenses for both patients and the system (39).

Among the evaluated studies, some (e.g., those conducted in Brazil by von Dolinger et al. and Perdiz et al.) reported infection rates exceeding 10% in TKA surgeries. Possible causes for the high prevalence in these studies include small sample sizes, environmental factors, and the lifestyle of the evaluated patients. Generally, characteristics such as risk factors for infection and underlying illnesses can be used to identify a lower incidence of SSIs. Additionally, factors like antibiotic prophylaxis, preoperative skin preparation procedures, and shorter surgery durations can directly reduce the prevalence of SSIs after TKA surgeries (23, 24, 34, 61, 62).

Furthermore, the results of this study demonstrated heterogeneity among the studies. One possible reason for this heterogeneity was the variation in sample sizes. Meta-regression findings accounted for approximately one-third of the heterogeneity, indicating that increased sample sizes are associated with a lower prevalence of infection. Another factor contributing to this variability could be the differing average ages of the samples across various studies. Younger individuals, due to their robust immune systems and lower frequency of underlying illnesses, naturally have reduced infection rates after surgery (36, 60).

Additionally, the populations studied varied in terms of surgical procedures. The TKA surgeries can be performed alone or in combination with other surgeries, such as total hip arthroplasty, femoral fractures, and tibia procedures. Generally, when two or more surgeries are performed simultaneously, the risk of infection may increase due to excessive bleeding and involvement of adjacent areas (63). Moreover, in several of the reviewed studies, the study population consisted solely of males undergoing TKA operations. According to research by Cohen et al., gender impacts postoperative infection rates (64). Consequently, the variety of outcomes may also be related to differences in individual gender.

Other factors associated with SSIs in TKA surgeries include the duration of the surgeries. Peersman et al. found that patients undergoing longer TKA surgeries had higher levels of SSIs (65). In another study, Poultsides et al. demonstrated that alcohol consumption increases the incidence of SSIs in TKAs, and individuals with alcoholism were determined to be at higher risk for infection (2). The findings of this research suggest that variations in any of the aforementioned scenarios might contribute to the heterogeneity of the results.

Additional factors associated with SSIs in TKA surgeries include the causes of surgery, obesity, malnutrition (66), race (67), reoperation of TKAs (54), penicillin allergy (68), smoking (69), use of closed drainage systems (70), and underlying diseases such as hypertension, electrolyte imbalances, respiratory problems, and blood disorders (54).

One limitation of the present study is the use of different methods for evaluating SSIs in patients, as varying tools can reduce the accuracy of the evaluation. In the analyzed studies, patients were assessed using questionnaires, checklists, observations, and electronic data. Therefore, it is advised that future research employ more methodologically comparable studies using the same instruments to achieve more accurate findings.

This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to separately assess SSI rates in TKAs and investigate the details and conditions of each study. It is recommended that future studies conduct more detailed classifications and measure the prevalence of infection based on age groups and gender. This approach would allow for a more precise determination of prevalence and the development of preventive solutions.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of the present study showed that the prevalence of SSIs in TKA surgeries was low, despite the heterogeneity among the evaluated studies. Given the significance of SSIs, particularly in high-risk surgeries such as TKAs, it is crucial to monitor their rates. These infections pose numerous challenges and incur expenses for both patients and the healthcare system. Considering the variation in SSI prevalence across different countries and conditions, standard and uniform protocols should be implemented to effectively reduce these infections in various regions.

In light of this, hospital managers should design training courses for patients and healthcare workers to enhance awareness of risk factors and preventive measures. Efforts should be made to control the factors that contribute to SSIs as much as possible.