1. Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) ranks as the fourth most common cause of death worldwide, causing 3.5 million deaths in 2021, accounting for approximately 5% of all global deaths (1). The global prevalence of COPD was estimated at 12% in 2019 and continues to increase (2). In Iran, the prevalence of this disease is estimated at 8.3% (3). Most patients with COPD also suffer from comorbidities, with psychological problems such as anxiety and depression being among the most common (1). The symptoms of anxiety and depression are likely related to the complex interactions involving the chronic nature of the illness, restrictions in physical activity, social isolation, the physiological impact of COPD on the brain, and genetic predispositions. These challenges contribute to a sense of demoralization and diminished self-efficacy, potentially facilitating the progression of psychopathological conditions (4). The prevalence of these problems is higher in patients with COPD than in the general population and even in patients with other chronic diseases. The prevalence of anxiety in patients with COPD ranges from 21% to 96%, while the prevalence of depression ranges from 27% to 79% (5). Anxiety and depression reduce activity tolerance and quality of life in these patients (6), as well as increase the severity of the disease, frequency and duration of hospitalization, and mortality (7).

Despite their importance, anxiety and depression are frequently mistreated. This is due to a prevailing medical culture that often neglects patients' psychological health. Additionally, healthcare professionals may feel unequipped to address emotional problems caused by physical illnesses. Patients may also face stigma when referred to psychiatric or psychological services, which can be perceived as devaluing their symptoms (8). These patients are often excluded from rehabilitation and self-management (SM) programs due to a belief that they cannot complete the programs. Therefore, it is crucial to manage anxiety and depression in these patients (6). One non-pharmacological intervention for treating anxiety and depression in these patients is SM programs (8). Self-management programs involve patient education that teaches the skills necessary to implement a disease-specific treatment regimen, provides guidance for health behavior change, and offers emotional support to help patients manage the disease and daily life functions (9). Self-management of COPD includes smoking cessation, self-recognition and treatment of exacerbations, exercise and increased physical activity, nutritional counseling, and management of dyspnea (10).

While some previous studies have rejected the effect of SM programs on anxiety and depression in patients with COPD (11, 12), recent studies have reported that these programs can effectively reduce anxiety and depression in these patients (13, 14).

2. Objectives

Therefore, further research is needed to explore the effects of SM programs on anxiety and depression in these patients. Due to the high prevalence of anxiety and depression in these patients, the significant impact of these conditions on patients with COPD, and the important role of SM programs in this disease, as well as the controversial results regarding their effects on anxiety and depression, this study was the first in Iran to investigate the effect of a SM program on anxiety and depression in individuals with COPD, according to the research team's searches.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This double-blinded randomized controlled trial was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (No. IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1398.155) and registered in the (Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials) with IRCTID: IRCT20160704028781N4 on May 14, 2020. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

3.2. Setting

This study was conducted at Hazrat Rasool Akram (PBUH) Hospital of Iran University of Medical Sciences and Imam Khomeini (RA) Hospital of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran from January 2020 to July 2022. These centers were selected due to the high admission rates of patients with COPD.

3.3. Participants

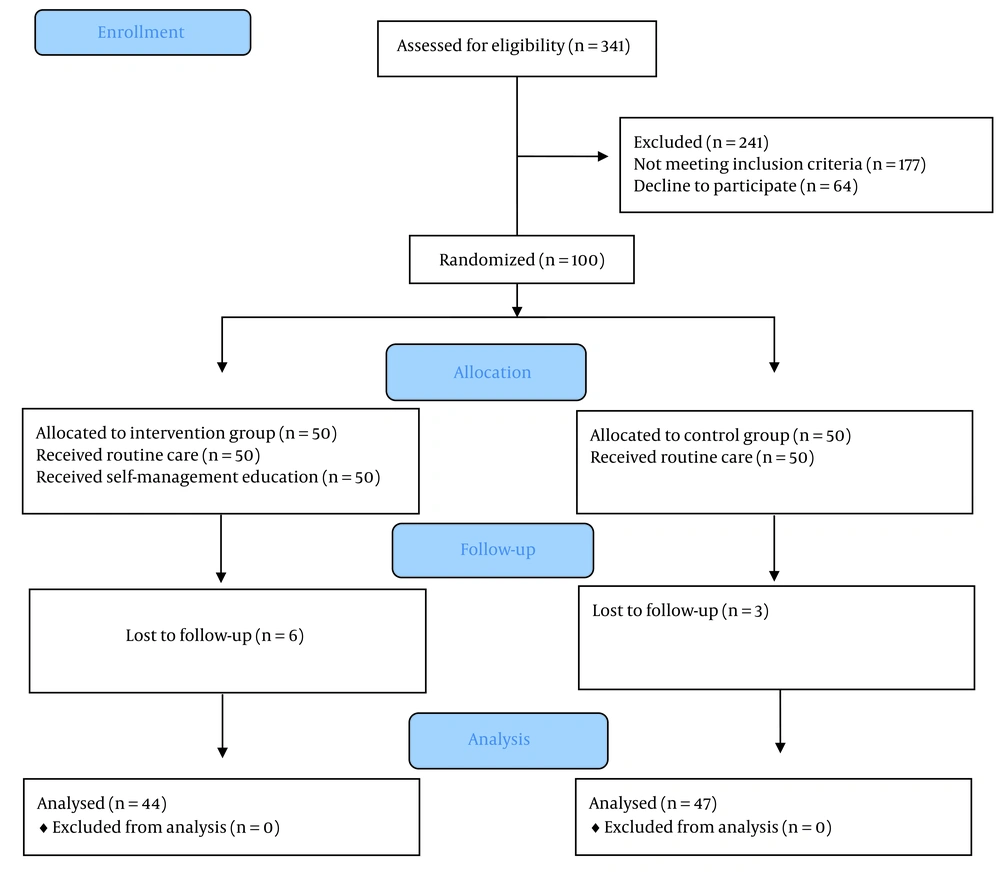

According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 100 patients with COPD were included in this study. The criteria included being 45 to 70 years old, having the disease confirmed by a pulmonologist, having a disease stage ≥ 2 (FEV1/FVC < 70%, FEV1 < 80%), being able to speak, read, and write Persian, being able to conduct interviews and complete questionnaires, not having participated in SM for COPD in the past, and not having hearing or communication problems or taking anti-anxiety or antidepressant medications. The exclusion criterion was having a life-threatening disease. A consecutive sampling method was used in this study. The researcher selected samples until the total sample size was reached according to the inclusion criteria, obtained informed consent, and randomly assigned participants to the control or intervention groups. Patients were randomly allocated from both hospitals. Allocation to groups was by random blocks with different numbers without permutation from each center. In this study, the outcome assessor and data analyst were blinded to group allocation. The sample size was calculated based on the Z-formula with a confidence level of 95% and a test power of 80%, assuming that changes of two units in the anxiety variable compared to the control group were considered statistically significant. The standard deviation from the study by Wang was considered to be 3.18 (15). The process of sample selection is shown in Figure 1.

3.4. Procedure

Initially, the patients completed the questionnaires. Both groups then received routine care and education. The researcher provided SM skills education through face-to-face sessions in the hospital and at the bedside. Educational resources, such as photos and videos viewed on laptops or cell phones, were utilized, along with various medications and inhalers for teaching purposes. The educational content was based on the "Health and COPD" book produced by the Australian Lung Foundation (16). This booklet is a valid and widely used resource in the field of SM for COPD and has been employed in several studies (17-19). The educational topics covered included lung physiology, diagnostic tests, risk factors, COPD medications, preventing and managing flare-ups, exercise, breathlessness, breathing control and energy conservation, airway clearance, home oxygen therapy, diet, swallowing, mental health, intimacy, travel, and community support services (16). Additionally, precautions related to the coronavirus were taught to these patients, as the study was conducted during the peak of the pandemic.

The educational program consisted of four 90-minute sessions over four consecutive days. After the first lesson, 30 minutes of each session were dedicated to reviewing the previous lesson's content, answering patients' questions, and presenting new material. The education was delivered by a researcher who had completed a patient education course. To prevent information sharing between the control and intervention groups, the researchers provided sufficient explanation to the intervention group regarding the importance of not disclosing information to other patients during the study. Members of the intervention group were contacted every two weeks during the first month and monthly thereafter to ensure proper implementation of SM measures and to address any questions.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Questionnaire was completed again by both the control and intervention groups at 6 and 12 months to assess the effect of the interventions. After the interventions, the control group was provided with the SM education booklet.

3.5. Instrument

The demographic questionnaire included age, gender, Body Mass Index (BMI), comorbidity, disease stage, smoking status, and smoking pack-years. This questionnaire was completed at the beginning of the study by reviewing medical records and interviewing the patient. The instrument used to measure anxiety and depression was the HADS, a 14-item self-report instrument that determines the presence and severity of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients. The questionnaire takes less than five minutes to complete and is suitable for individuals aged 16 and over. The instrument includes an anxiety subscale and a depression subscale. To reduce the potential for false-positive diagnoses, physical symptoms have been eliminated. Seven items of this scale relate to anxiety and seven to depression. Each item is scored from 0 to 3. Of the total of 21 points that can be achieved in each subscale, a score of more than eight indicates the presence of anxiety and depression. For both subscales, scores range from 0 to 7 (normal), 8 to 10 (mild), 11 to 14 (moderate), and 15 to 21 (severe). This questionnaire has been used in various studies. Kaviani et al. reported the validity of the questionnaire with a Cronbach's alpha of 85% for the anxiety subscale and 70% for the depression subscale, and test-retest reliability was reported as r = 0.77 (P < 0.001) for the depression subscale and r = 0.81 (P = 0.001) for the anxiety subscale (20).

The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) is a short, simple, validated, and widely used instrument to assess the impairment of health status in COPD (21). This instrument consists of eight items scored from 0 to 5 points. The CAT score ranges from 0 to 40, with a score of 0 indicating no impairment. The reliability of this instrument was confirmed by a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.88, and it has a high correlation with other instruments used to assess the health status of patients with COPD (22).

The Medical Research Council Modified Scale (mMRC) is an instrument for assessing the severity of dyspnea. The total score of this instrument ranges from 0 to 4, with a score of 0 indicating almost no dyspnea and a score of 4 indicating complete disability of the patient due to dyspnea. All items are related to daily activities, and the score can be calculated in a few seconds (23). The validity of the mMRC Scale was confirmed in Iran in the study by Hossein Pour et al. using face and qualitative content validity methods, and its reliability was calculated with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.8 (24). The patients also completed this questionnaire.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 23.0 (SPSS 23.0). Descriptive statistics were employed to present the demographic data of the sample. The normality of the data distribution was confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Other inferential statistics, including the chi-square test, independent t-test, and multiple regression analyses, were also used to analyze the data.

4. Results

A total of 341 patients were screened for eligibility, with 100 patients included in the study and 91 patients included in the final analysis. The sample selection process, based on the PRISMA flow diagram, is illustrated in Figure 1. The mean age was 61.21 years in the control group and 60.11 years in the intervention group. The majority of participants in both groups were men in the third stage of the disease and were ex-smokers. The average pack-years in the control group was 33.14, and in the intervention group, it was 33.42. More than two-thirds of individuals in both groups had comorbidities, with heart disease being a common comorbidity. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age, gender, BMI, smoking status, pack-years, disease stage, comorbidities, cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, respiratory disease, other diseases, CAT score, and mMRC score. The characteristics of the study samples are shown in Table 1.

| Variables and Groups | Control (n = 47) | Intervention (n = 44) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 61.21 ± 6.23 | 60.11 ± 6.63 | 0.417 |

| Gender | 0.326 | ||

| Male | 32 (68.1) | 34 (77.3) | |

| Female | 15 (31.9) | 10 (22.7) | |

| BMI | 23.59 ± 4.90 | 24.17 ± 4.09 | 0.545 |

| Smoking | 0.294 | ||

| Non smoker | 3 (6.4) | 7 (15.9) | |

| Smoker | 12 (25.5) | 8 (18.2) | |

| Ex-smoker | 32 (68.1) | 29 (65.9) | |

| Pack (y) | 33.30 ± 12.20 | 33.24 ± 12.09 | 0.985 |

| Stage | 0.814 | ||

| 2 | 15 (31.9) | 14 (31.8) | |

| 3 | 19 (40.4) | 20 (45.5) | |

| 4 | 13 (27.7) | 10 (22.7) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 29 (61.7) | 25 (56.8) | 0.636 |

| Metabolic diseases | 18 (38.3) | 16 (36.4) | 0.849 |

| Respiratory diseases | 11 (23.4) | 13 (29.5) | 0.506 |

| Other diseases | 20 (42.9) | 19 (43.2) | 0.985 |

| CAT score | 23.04 ± 6.05 | 22.93 ± 6.20 | 0.931 |

| mMRC score | 2.70 ± 1.10 | 2.41 ± 1.25 | 0.237 |

Abbreviations: mMRC, Medical Research Council Modified Scale; CAT, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

4.1. Anxiety

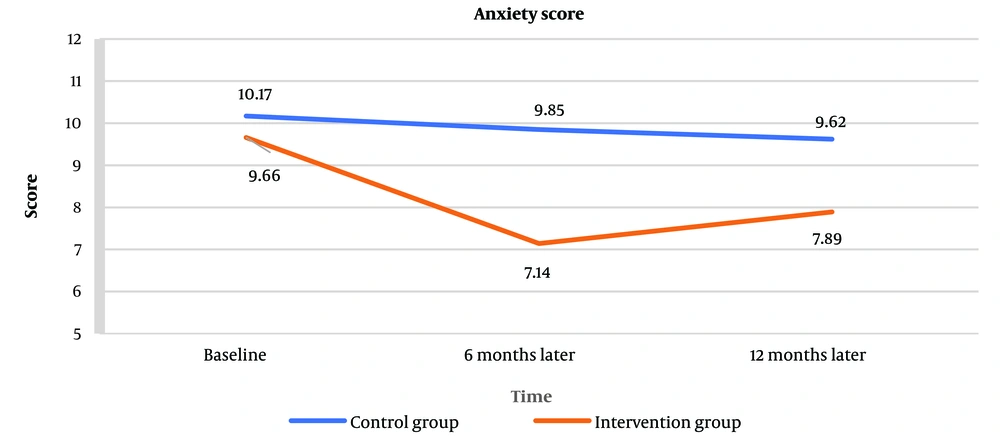

As shown in Table 2, at baseline, the mean anxiety score of the control group was 10.17 ± 5.06, and the mean anxiety score of the intervention group was 9.66 ± 5.03. The HADS anxiety scores at baseline did not differ between groups (P = 0.630). After six months, the mean anxiety score decreased to 9.85 ± 5.25 in the control group and 7.14 ± 4.32 in the intervention group. The difference between groups was significant, with the anxiety score of the intervention group being lower than that of the control group (P = 0.009). After 12 months, the mean HADS anxiety score was 9.62 ± 4.93 in the control group and 7.89 ± 4.55 in the intervention group. Although the anxiety score of the intervention group decreased compared to the control group, there was no significant difference in anxiety scores between the groups (P = 0.086). The line graph of the mean anxiety score for the control and intervention groups is illustrated in Figure 2.

| Group and Times | Control (n = 47) | Intervention (n = 44) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 10.17 ± 5.06 | 9.66 ± 5.03 | 0.630 |

| Six months later | 9.85 ± 5.25 | 7.14 ± 4.32 | 0.009 |

| Twelve months later | 9.62 ± 4.93 | 7.89 ± 4.55 | 0.086 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.2. Depression

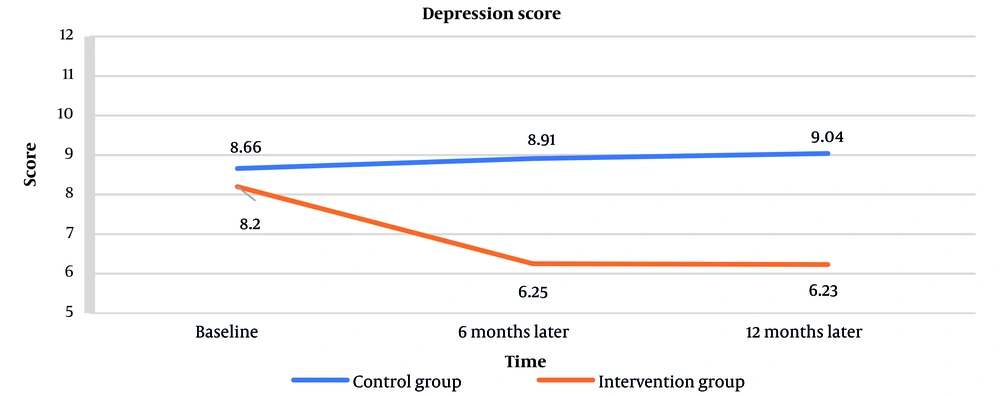

As shown in Table 3, the baseline depression score was 8.66 ± 4.76 in the control group and 8.20 ± 4.67 in the intervention group, with no significant difference between groups (P = 0.647). After six months, the depression score was 8.91 ± 4.80 in the control group and 6.25 ± 3.76 in the intervention group. After twelve months, the scores were 9.04 ± 4.86 in the control group and 6.23 ± 3.67 in the intervention group. There were significant differences between groups at both time points (P = 0.004 and P = 0.002, respectively). The line graph of the mean depression score for the control and intervention groups is illustrated in Figure 3.

| Group and Times | Control (n = 47) | Intervention (n = 44) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8.66 ± 4.76 | 8.20 ± 4.67 | 0.647 |

| Six months later | 8.91 ± 4.80 | 6.25 ± 3.76 | 0.004 |

| Twelve months later | 9.04 ± 4.86 | 6.23 ± 3.67 | 0.002 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

4.3. Factors Predict Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients

Multiple regression analysis indicated that significant predictors of anxiety in patients with COPD included smoking (P = 0.043), stage of disease (P = 0.007), CAT score (P = 0.021), and mMRC score (P = 0.005). Significant predictors of depression in COPD patients were smoking (P = 0.037), stage of disease (P = 0.023), having comorbidities (P = 0.004), CAT score (P < 0.001), and mMRC score (P = 0.003). All of these variables were positively associated with anxiety and depression in COPD patients. The predictors of anxiety and depression in COPD patients are shown in Table 4.

| Variables | Anxiety a | Depression b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta | P-Value | B | SE | Beta | P-Value | |

| Gender | 1.333 | 0.796 | 0.121 | 0.099 | 0.682 | 0.690 | 0.067 | 0.326 |

| Age | -0.016 | 0.054 | -0.021 | 0.764 | -0.006 | 0.047 | -0.009 | 0.897 |

| BMI | 0.027- | 0.076 | 0.025- | 0.724 | 0.024- | 0.065 | -0.024 | 0.716 |

| Smoking | 1.929 | 0.937 | 0.176 | 0.043 | 1.721 | 0.811 | 0.169 | 0.037 |

| Pack (y) | -0.024 | 0.030 | -0.060 | 0.431 | -0.021 | 0.026 | -0.056 | 0.425 |

| Stage | 1.688 | 0.613 | 0.287 | 0.007 | 1.232 | 0.531 | 0.225 | 0.023 |

| Comorbidity | 1.058 | 0.759 | 0.102 | 0.167 | 1.963 | 0.657 | 0.204 | 0.004 |

| CAT score | 0.226 | 0.096 | 0.266 | 0.021 | 0.316 | 0.083 | 0.400 | 0.001 > |

| mMRC score | 1.159 | 0.397 | 0.270 | 0.005 | 0.566 | 0.343 | 0.142 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; mMRC, Medical Research Council Modified Scale; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Model 1: Predicting anxiety in COPD patients, R2 = 0.820.

b Model 2: Predicting depression in COPD patients, R2 = 0.846.

5. Discussion

In the present study, the effect of a SM program on anxiety and depression in individuals with COPD was investigated. According to the research team's searches, this study is the first of its kind conducted in Iran. The findings indicated that initially, the mean anxiety and depression scores in both groups were higher than normal and at a mild level. Anxiety scores in the intervention group decreased at 6 and 12 months post-intervention, whereas depression scores in the intervention group decreased only at 6 months post-intervention and were no longer significant at 12 months. Individuals with COPD are at a higher risk for anxiety and depression (1). Although these comorbidities negatively impact physical and social functioning—such as decreased physical performance, social interaction, self-esteem, increased physical disability, caregiver dependence, and emotional distress — and adversely affect hospitalization duration, disease exacerbation, quality of life, and mortality in COPD patients, they are often underdiagnosed and undertreated (8, 25).

Other studies investigating the effects of SM on anxiety and depression in COPD patients have not reached clear conclusions. Wang et al. found that a health coaching SM program reduced anxiety and depression in COPD patients (14). Lou et al. reported that the number of patients with anxiety and depression in the intervention group receiving the COPD health management program was lower than in the control group after four years of follow-up (26). Lamers et al. demonstrated that a minimal psychological intervention (MPI) based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) principles and SM alleviated depression in depressed COPD patients 9 months post-intervention, but had no effect after 1 or 3 months (27). Studies by Apps et al., Bucknall et al., and Mitchell et al. indicated that SM for COPD patients improves anxiety but has no significant effect on depression (28-30). A meta-analysis showed that nurse-driven SM programs reduced anxiety and depression in COPD patients (13). After 12 months, Jonsdottir et al. found that a partnership-based SM program for patients with mild and moderate COPD did not reduce anxiety or depression in either the intervention or control group (31). A meta-analysis by Cannon et al. concluded that SM interventions for COPD had no significant effect on anxiety and depression in these patients (11). Jolly et al. conducted another meta-analysis showing that community-based SM interventions did not improve anxiety and depression in COPD patients in primary care (12). The differences in results could be attributable to variations in the content of the SM program, its implementation, and differences in the characteristics of the samples studied.

The present study also demonstrated that dyspnea is associated with anxiety and depression. This association has been reported repeatedly in previous studies (32-35). Anxiety is known to increase respiratory rate, leading to rapid and shallow breathing patterns and worsening dyspnea in COPD patients (36). The relationship between dyspnea and depressive symptoms in COPD patients can be explained by complex causal processes (37). We found that smoking status is related to anxiety and depression, consistent with prior studies (6, 34, 38). Smoking can promote anxiety and depression, likely due to central nervous system toxicity caused by the constituents of tobacco smoke, as well as nicotine withdrawal (39). Symptoms of depression in patients with COPD are associated with less successful smoking cessation (40), and depressed individuals are more likely to smoke, while smokers are more likely to be depressed (8).

The findings of this study are consistent with previous studies that have associated anxiety and depression in patients with COPD with their disease stage (41-43) and CAT score (35). Although studies by Blanchette et al. and Miravitlles et al. show a relationship between comorbidity and depression similar to the results of our study (44, 45), several studies reported no association between comorbidity and anxiety and depression (40, 46). Additionally, several studies reported higher anxiety and depression in women than in men (41, 42, 47) and an association between BMI and anxiety and depression (42, 48), but we found no association between gender and BMI with anxiety and depression. These contradictory results could be explained by differences in the study samples.

The most important difference between this study and others is that it was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a significant impact on COPD patients, and our educational content included information about the importance and prevention strategies for COVID-19.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

The main strengths of this study include its well-designed methodology, randomization, and the involvement of a team of experts in all phases of the research. Nevertheless, there were several limitations. First, the study sample was based on convenience sampling, and the sample size was relatively small. Second, the research setting was limited to two sites. Third, having the capacity to read and write as an inclusion criterion led to the exclusion of a large number of participants who were screened for eligibility. Fourth, demographic information was not collected from those who did not participate in the study, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. Fifth, although the reduction in depression scores in the intervention group was significant at both time points, the reduction in anxiety scores was significant only 6 months after the intervention and was no longer significant 12 months later. This may indicate that the timing of the intervention is an important factor influencing changes in anxiety scores, and a longer follow-up period may reveal more details about these changes. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies consider a larger sample size, a more robust sampling method, multiple sites, and a longer follow-up period.

5.2. Implications for Nursing Practice

The results of this double-blinded randomized controlled trial demonstrated a positive effect of the SM education program on reducing anxiety and depression in patients with COPD. Based on the findings of this study, healthcare providers can incorporate SM programs into the care of these patients, as they represent an important and feasible approach to improving psychological outcomes and a positive step toward addressing this often-overlooked dimension in these patients. Additionally, healthcare policymakers can consider including SM programs in COPD management guidelines with more evidence and certainty. Given the high levels of anxiety and depression observed at baseline in the study samples, healthcare policymakers can plan to involve psychologists and psychiatrists in the treatment team for these patients.

5.3. Conclusions

The results of this double-blinded randomized controlled trial demonstrated a positive effect of the SM education program on reducing anxiety and depression in patients with COPD. Therefore, given the high prevalence of anxiety and depression and the lack of attention to these psychological dimensions in these patients, SM education programs delivered by healthcare providers represent an important and feasible approach to treating anxiety and depression in this population.