1. Background

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases among women worldwide. Studies have shown that from 1990 to 2019, the incidence of breast cancer increased by 14.31% in women, particularly among those aged 35 to 60, with a significant rise projected among women aged 50 to 54 from 2020 to 2044 (1). Research indicates that breast cancer poses a major health challenge globally, with regions having low socio-demographic indicators expected to bear the greatest burden of care and treatment in the future (2, 3). An increasing trend in cancer incidence was observed in Iran from 2003 to 2017, particularly in the age groups of 65 - 69 years (128.33 per 100,000 women) and 60 - 64 years (127.79 per 100,000 women) (4). Individuals with cancer often face issues such as anxiety, depression, uncertainty, reduced quality of life, body image concerns, and specific problems due to physical symptoms (5). Okuyama et al. found that breast cancer causes chronic fatigue, including physical fatigue due to depression, pain, and medication use; affective fatigue due to anxiety and depression; and cognitive fatigue due to anxiety and pain (6). Anxiety and depression play a crucial role in inducing these types of fatigue. Recognizing cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and aiding in pain reduction and mental health improvement can enhance the recovery process (7). Physical and psychological interventions can alleviate the mental and physical stress caused by cancer (8). One such therapy is mindful yoga, which emphasizes present awareness, specific body positions, regular breathing, and meditation, along with the conscious reception of thoughts, feelings, and actions to reduce physical and psychological fatigue (8, 9). Mindful yoga shows significant potential for breast cancer patients. Studies have demonstrated that patients who practice yoga regularly experience notable improvements in physical health, mental health, and sleep quality, as well as reductions in anxiety, depression, stress, fatigue, and pain intensity after exercise (9, 10).

Research shows that CRF is a challenging consequence of cancer treatment. Findings have revealed that physical activities, exercise, yoga, psychosocial therapeutic interventions, and mindfulness-based therapies can help reduce fatigue symptoms in breast cancer patients (11, 12). Moreover, mindfulness-based fitness training (MBFT) has been effective in improving the performance and sexual satisfaction of women with breast cancer (13). Additionally, mindfulness-based therapy is generally associated with less pain and reduced fatigue, anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders in women with cancer (14). Mindful yoga therapy is beneficial in the early stages of chemotherapy for breast cancer patients. This therapy is also effective in improving physical performance and reducing anxiety and depression, thereby enhancing overall physical and mental health and increasing the quality of life for breast cancer patients in the early stages of disease diagnosis (15, 16). Another study showed that performing aerobic exercises and yoga improved breast cancer patients' functional capacity and quality of life. The findings also indicated that aerobic exercise programs and yoga aid in physical and mental rehabilitation and improve patients’ psychosocial health (17). Furthermore, exercise and yoga are more effective when used as non-pharmacological interventions and complementary medicine for women undergoing chemotherapy in the early stages of breast cancer diagnosis (18, 19). Mindful yoga can benefit women with breast cancer through the simultaneous implementation of relaxation, meditation, and moment-to-moment awareness. Previous studies have introduced yoga, parallel sports, and mindfulness as emerging complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies for fatigue caused by breast cancer. However, the combination of mindfulness with yoga, first proposed by Boccio (19), has received less attention for helping women with breast cancer. Moreover, no study has yet focused on this intervention for multifaceted fatigue in women with breast cancer.

2. Objectives

The present study sought to examine the effectiveness of mindful yoga on fatigue in women with breast cancer.

3. Methods

This quasi-experimental study employed a pre-test and post-test design with a control group. The research population consisted of all women with stage 2 and stage 3 breast cancer (n = 258) who visited the cancer care department of the Mehr Cancer Patient Support Center in Shahin Shahr for periodic care in 2023. The participants' ages ranged from 35 to 50 years. Given the nature of the disease, participants were selected from voluntary patients using convenience sampling based on the inclusion criteria. Fleiss et al.’s sample size formula was used to estimate the sample size (20). The estimated sample size for each group was 20 participants, totaling 40 participants:

Where β = 0.9, P0 = 0.8, P1 = 0.91, r = 1.4 and α = 0.05.

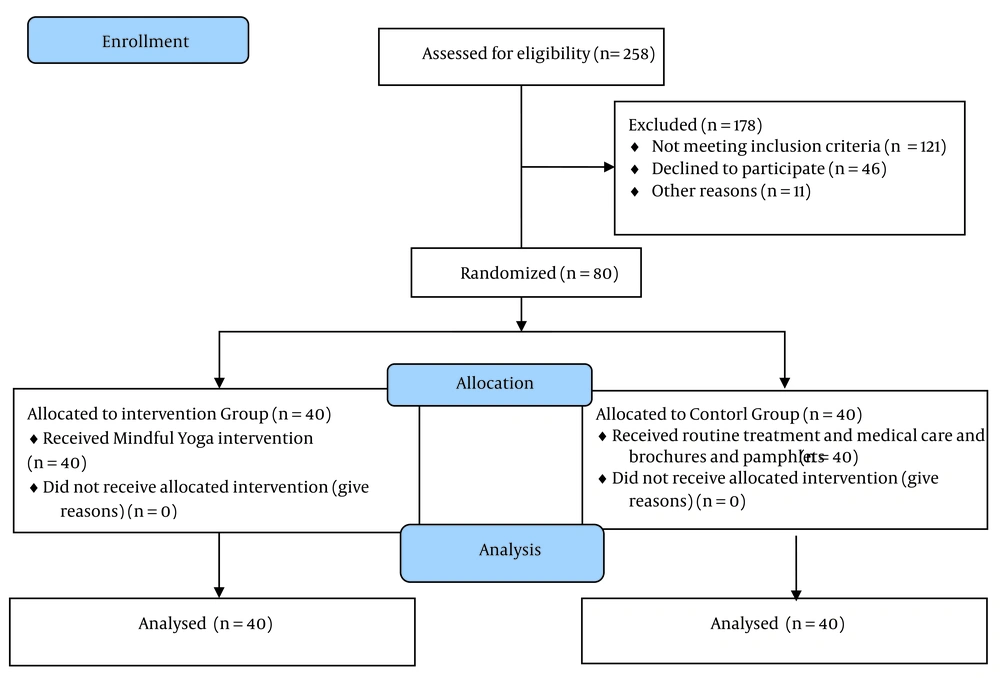

A total of 40 eligible participants were selected through convenience sampling and placed into two groups: Intervention and control (20 participants each). Subsequently, the selected patients were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups using permuted block randomization, where each "block" contained a specified number of randomly ordered assignments (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria for enrollment in the study were as follows: (1) Undergoing common medical procedures; (2) having at least a middle school education to comprehend the statements in the scale, and (3) obtaining a score of 1 standard deviation above the average on the Cancer Fatigue Scale.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) Suffering from physical problems or disabilities that hindered the ability to perform yoga exercises; (2) simultaneous participation in other psychological, mental health, or sports programs or courses; (3) absence from more than 3 intervention sessions; (4) having an underlying disease diagnosed by the therapy center's doctor; (5) having psychological problems diagnosed by the center's psychologist; and (6) sustaining an injury during the intervention program. Additionally, patients were free to leave the intervention sessions for any reason. Patients found to be in a metastable state after medical examinations were also excluded from the intervention sessions.

The patients in the intervention group participated in mindful yoga sessions for 16 weeks, with each session lasting 75 minutes. Meanwhile, patients in the control group continued their routine treatment and medical care, and they received brochures and pamphlets related to healthy eating and personal care. The Cancer Fatigue Scale was administered to participants in both groups before and after the intervention sessions.

The study protocol was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research (IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1402.403). Prior to the study, patients received instructions about the research procedure and intervention sessions. Informed written consent was obtained from patients in both groups, ensuring them that their information would remain anonymous and confidential. Additionally, to adhere to ethical protocols, eight yoga sessions were offered to patients in the control group at the conclusion of the study.

3.1. Instrument

The Cancer Fatigue Scale, developed by Okuyama et al., consists of 15 items divided into three subscales: Physical fatigue (items 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15), affective fatigue (items 5, 8, 11, and 14), and cognitive fatigue (items 4, 7, 10, and 13). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much), reflecting the patient's recent condition. The severity of physical, affective, and cognitive fatigue is thus measured, with overall scores ranging from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate greater severity of fatigue. Specifically, physical fatigue scores range from 0 to 28, affective fatigue from 0 to 16, cognitive fatigue from 0 to 16, and overall fatigue from 0 to 60 (6).

The scale was first translated into Persian by Haghighat et al., with reliability indicators for the physical, affective, and cognitive fatigue subscales and the entire scale, measured by Cronbach's alpha, reported as 0.92, 0.89, 0.85, and 0.94, respectively (21). In this study, the reliability of the physical, affective, and cognitive fatigue subscales was estimated at 0.89, 0.91, and 0.90, respectively, with the reliability of the entire scale reported as 0.94.

3.2. Procedure

The intervention sessions commenced after obtaining the necessary permits from the Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research. Prior to initiating the yoga exercise protocol, a briefing session was held at the hospital with the presence of medical staff, attending physicians, midwives, and nurses, during which the objectives of the mindful yoga intervention were explained to the patients. Additionally, a written informed consent form and a personal information form, which assessed the patient’s marital status, number of children, occupation, education, menopause status, age, medical records, surgical history, duration of the disease, and medications, were completed by patients in both groups.

Patients in both the intervention and control groups received instructions about yoga exercises. The patients’ heart rate and Body Mass Index (BMI) were measured by doctors and midwives, and those with any health problems were excluded from the study. Mindful yoga exercises were conducted over 16 weekly sessions, each lasting 75 minutes. The sessions included ten minutes of warm-up, one hour of yoga and mindfulness exercises, and relaxation at the end, as suggested in the literature (20, 22, 23). All training was led by a midwife (first author) who was a certified mindful yoga instructor. For additional supervision, all training classes were conducted with the assistance of nurses and midwives. Table 1 provides a summary of the content and goals of the mindful yoga sessions.

| Sessions | Goals and Content | Homework Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| Briefing sessions | Introducing the instructor and the participants, providing some instructions about the research objectives and procedure to the participants, introducing yoga, completing the pre-test, and introducing the yoga exercises to be performed in the 16 intervention sessions | Performing breathing exercises |

| 1 | Providing some information about breast cancer and stating that mindful yoga tries to control the disease and not eradicate it, performing exercises with Shavasana while focusing on the present moment | Teaching the samurai metaphor followed by self-love to awaken clients’ cellular memory of the body and skin by touching the surface of the body. |

| 2 | Providing instruction about daily exercises in a suitable place, teaching sleep hygiene and a balanced lifestyle, Yama (moral behavior) and Niyama (healthy habits) exercises, healthier eating, cleaning the living environment, planting trees, maintaining contact with nature, performing Kriya (purification) exercising, and avoiding eating meat and sugar for two weeks, performing Pavanamuktasana exercises (the wind-relieving posture) with full awareness and mindfulness of the inner body | Performing Pranayama exercises by raising arms to both sides, breathing with light followed by Shavasana exercises, teaching calming and energizing breathing techniques (pranayama), taking notes of daily exercises, and performing regular yoga exercises at home |

| 3 | Asking the patients to focus all their attention and senses on a specific point so that the inflammations are removed. | Deep inhalation and exhalation exercises |

| 4 | Performing Pawanamuktasana as the first relaxation technique followed by abdominal breathing, focused meditation, reviewing homework, teaching physical exercises related to the disease (disease-related asanas), performing the mindful listening technique | Performing a short groin massage |

| 5 | Performing respiratory relaxation, body mindfulness, doing homework, doing mind cleaning exercises, using the metaphor of tug-of-war with monsters, practicing eating with mindfulness, relaxing from toes to hands, neck, and eyes | Asking the participants to do yoga nidra and relaxation before going to sleep and sleep well |

| 6 | Performing the laughing and boat technique with inhalation and exhalation followed by underarm massage | The participants were asked to massage their hands from top to bottom towards the lymph nodes followed by groin massage and the relaxation exercise at home. |

| 7 | Teaching abdominal breathing, Surya Bhedana Pranayama and Chandra Bhedana Pranayama (breathing through the right and left nostrils) followed by Pawan exercises in a standing position and choral singing to remove the pressure from the throat | Yoga Nidra (conscious sleep) and meditation |

| 8 | Surya Bhedana Pranayama and Chandra Bhedana Pranayama breathing to create balance, standing with different rotations, awareness of each pavan, dancing with rhythm, and playing the games that calm the mind while paying attention to the sound of music in silence to create concentration. | Relaxation with breathing and yoga with balls |

| 9 | The use of mindfulness techniques (e.g. focusing on the present), contrast between experience and mind, and practicing compassion in the mirror | Relaxation with breathing, Pawan with mindfulness, hand massage, lymph node massage, yoga nidra with rotation of consciousness |

| 10 | Performing mindfulness, dance meditation, energy cycles, and Shavasana with rotation of consciousness | Dance meditation exercise |

| 11 | Relaxation with conscious inhalation and exhalation, yoga with a ball, Pawan Muktasanas with mindfulness, and yoga asanas with mindfulness | Hand massage and yoga nidra with visualization |

| 12 | Relaxation with conscious breathing, Pawanmuktasana asana with mindfulness, asanas with inhalation and exhalation, yoga nidra with rotation of consciousness and visualization | Practicing rotation of consciousness and visualization of inner peace |

| 13 | Relaxation with conscious breathing, Pawanmuktasana with inhalation and exhalation and mindfulness, pre-pranayama exercises, laughter yoga, yoga nidra with rotation of consciousness | Performing laughter yoga at home |

| 14 | Relaxation with mindful inhaling and exhaling, pre-pranayama exercises with mindfulness, breathing movements, and full yoga nidra | Full nidra exercise at home |

| 15 | Performing relaxation with mindful inhaling and exhaling, trataka (candle meditation), savasana, motivating change, and empowering women | Candle meditation exercise |

| 16 | The technique of focusing on the present, mindfulness, reviewing the experiences of previous sessions, commitment to change, summarizing the content of sessions, and administering the post-test | Performing mindful yoga at home |

3.3. Data Analysis

The data were managed and summarized using descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation. The chi-square test was employed to measure differences between the means of the two groups. Additionally, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used to examine the effect of the mindful yoga intervention on cancer fatigue in women with breast cancer. Prior to conducting MANCOVA, its assumptions were verified, including the homogeneity of variances, regression slope, and normality of the data. The MANCOVA was then performed using SPSS-26 software at P < 0.05.

4. Results

The analysis of participants’ demographic data, including education, marital status, occupation, and stages of the disease, indicated that the average age of patients in the control group was 46.60 ± 6.57 years, while the average age of patients in the intervention group was 47.86 ± 8.28 years. Other demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 2.

| Variables and Categories | Intervention Group (N = 20) | Control Group (N = 20) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 0.617 | ||

| Diploma | 14 (70) | 13 (65) | |

| Master’s/bachelor’s degree | 6 (30) | 7 (35) | |

| Marital status | 0.821 | ||

| Married | 15 (75) | 16 (80) | |

| Single | 5 (25) | 4 (20) | |

| Occupation | 0.720 | ||

| Housewife | 13 (65) | 14 (70) | |

| Employed | 7 (35) | 6 (30) | |

| Cancer stage | 0.693 | ||

| Stage 2 | 16 (80) | 17 (85) | |

| Stage 3 | 4 (20) | 3 (15) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Chi-square test.

As shown in Table 3, the post-intervention scores for the three cancer fatigue subscales physical, affective, and cognitive decreased significantly in the intervention group compared to the control group following the mindful yoga intervention.

| Variables and Stages | Intervention Group (N = 20) | Control Group (N = 20) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical fatigue | 0.012 | ||

| Pre-intervention | 14.52 ± 4.73 | 13.26 ± 6.80 | |

| Post-intervention | 6.80 ± 2.48 | 12.93 ± 7.36 | |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Affective fatigue | 0.021 | ||

| Pre-intervention | 10.60 ± 2.02 | 9.60 ± 6.61 | |

| Post-intervention | 4.22 ± 1.30 | 8.88 ± 4.56 | |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Cognitive fatigue | 0.029 | ||

| Pre-intervention | 9.20 ± 2.51 | 8.88 ± 5.13 | |

| Post-intervention | 4.06 ± 1.75 | 8.05 ± 2.08 | |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Total cancer fatigue | 0.015 | ||

| Pre-intervention | 32.73 ± 12.68 | 31.24 ± 12.58 | |

| Post-intervention | 15.20 ± 5.50 | 30.98 ± 11.32 | |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

c Independent samples t-test.

Prior to conducting MANCOVA, the assumptions of the test were evaluated using Levene’s and Box’s M tests. As the results were not significant (P > 0.05), MANCOVA was subsequently performed. The Wilks' lambda test (Table 4) was employed to compare the independent variables between the two groups using MANCOVA.

| Test | Statistic | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks' lambda | 0.731 | 5.930 | 4 | 21 | 0.005 | 0.49 |

As shown in the table above, there was a significant difference between the control and intervention groups regarding the dependent variables. Mindful yoga, as the independent variable, accounted for 49% of the variance in the dependent variable (cancer fatigue).

As shown in Table 5, the effect size values for the impact of mindful yoga on cancer fatigue, physical fatigue, affective fatigue, and cognitive fatigue were 0.149, 0.176, 0.120, and 0.164, respectively. These values indicate that mindful yoga was effective in reducing CRF in women with breast cancer.

| Independent Variable and Source of Changes | Sum of Squares | df | MS | F | Eta | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindful yoga | ||||||

| Total fatigue score | 670.625 | 1 | 670.625 | 4.189 | 0.149 | 0.041 |

| Physical fatigue | 175.249 | 1 | 175.249 | 5.138 | 0.176 | 0.033 |

| Affective fatigue | 34.534 | 1 | 34.534 | 4.679 | 0.048 | 0.120 |

| Cognitive fatigue | 47.337 | 1 | 47.337 | 5.401 | 0.016 | 0.164 |

5. Discussion

The present study examined the effectiveness of mindful yoga in alleviating cancer fatigue in women with breast cancer. The findings demonstrated that the mindful yoga intervention was effective in improving all dimensions of CRF, with a particularly notable impact on reducing physical fatigue. Previous studies have similarly highlighted the benefits of yoga and mindfulness in mitigating fatigue associated with cancer, both before and after interventions. Consequently, yoga can be integrated into therapeutic regimens to reduce fatigue and depression in cancer patients (24). Another study indicated that yoga, along with aerobic and physical exercises, contributes to a reduction in CRF, which is a prevalent cause of physical disability in women with breast cancer (25). Furthermore, yoga has been shown to effectively reduce fatigue, depression, and anxiety, while improving sleep disorders and quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (26, 27). Combining yoga with self-training and mindfulness strategies can enhance the reduction of CRF in women with breast cancer, increasing the effectiveness beyond yoga alone (28). Additionally, yoga is beneficial for improving physical and cognitive fatigue in other age groups, including older women with cancer, who have found yoga to be a suitable method for reducing multifaceted physical fatigue, particularly physical fatigue (29).

The findings from the present study suggest that the mindful yoga intervention had a greater effect on physical fatigue in women with breast cancer compared to affective and cognitive fatigue. Physical fatigue, characterized by feelings of weakness, tiredness, and lethargy, can significantly impair daily functioning and quality of life in individuals with breast cancer. This finding aligns with the physical nature of yoga exercises, which involve gentle movements, stretching exercises, and controlled breathing techniques aimed at improving physical strength, flexibility, and quality of life in women with breast cancer (30, 31). Engaging in regular yoga exercises at home enables women with breast cancer to become more physically alert and aware of their physical conditions. Additionally, mindful yoga reduces muscular endurance, leading to a decrease in physical fatigue levels (32). By incorporating mindfulness-based exercises, such as focused attention on the self and bodily sensations, yoga encourages participants to cultivate present-moment awareness and acceptance of physical sensations, thereby promoting relaxation and reducing bodily tension (20).

The findings also indicate that mindful yoga reduced emotional fatigue in women with breast cancer. Mindful yoga encourages individuals to be aware of their thoughts and feelings moment by moment, to accept their emotional experiences, and ultimately to enhance emotional and psychological flexibility (20, 33, 34).

5.1. Conclusions

The data from the present study suggest that practicing mindful yoga is effective in reducing CRF in women with breast cancer, with significant implications for clinical practice and patient care. To address CRF holistically, oncologists, midwives, healthcare providers, nurses, and rehabilitation counselors can incorporate mindful yoga into their care and support protocols for breast cancer patients. Organizing accessible and affordable yoga courses, collaborating with yoga instructors and oncologists, promoting long-term participation in mindful yoga practices at home, offering a mindful yoga program alongside other care programs, and providing support resources — such as training videos, pamphlets, and computer programs — for patients to practice yoga at home can contribute to reducing CRF.

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

This study explored the use of mindful yoga as a complementary therapy to manage fatigue caused by cancer, acknowledging that it is not a definitive treatment for breast cancer. Breast cancer patients can incorporate mindful yoga alongside their routine medical and pharmaceutical regimens as a strategy to control physical, cognitive, and affective fatigue. The data were collected exclusively from women with breast cancer attending the Mehr Cancer Patient Support Center in Shahin Shahr, Isfahan province, Iran. It is important to note that cancer fatigue, as a psychological variable, is influenced by numerous factors. The study employed a quasi-experimental design, and due to the nature of the disease, participants were selected through convenience and voluntary sampling, resulting in a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, practical implementation requires trained instructors and patient commitment, which can be challenging. Consequently, it was not possible to control all intervening factors in this study. Future research could investigate the impact of mindful yoga on sleep quality and individual well-being in affected patients. Further studies could also explore the long-term effects and additional dimensions, such as emotional well-being or cognitive improvements.