1. Background

Suicide is a global phenomenon and challenge. In 2016, suicide accounted for 1.4 percent of all deaths worldwide. In 2016, it was the second leading cause of death among the population aged 15 - 29. It is estimated that 24% of people who report suicidal ideation eventually take action (1). In a study of students, Garlow et al. found that 11.1 percent of students had suicidal ideation in the last four weeks, and 16.5% had attempted suicide or experienced self-harm episodes in their lifetime (2). Mousavi et al., in a study conducted in Isfahan universities, showed that 26% of students had suicidal ideation (3). In addition to these statistics, evidence suggests that for every adult who commits suicide, more than 20 others may have attempted suicide (4).

One of the important underlying factors in the phenomenon of suicide and suicidal ideation is early life experiences. Early life experiences have a far-reaching, long-term impact on children's behavioral and psychological development (5). Negative early life experiences are one of the risk factors that have been studied empirically in recent years and are significantly associated with an increased risk of psychological pathology such as anxiety and depression (6). Early life experiences contribute to the psychological pathology of several disorders in early adulthood, including major depression, anxiety, destructive behaviors, antisocial behaviors, substance abuse (7), psychosis (8), and suicidal behaviors (9). Early life stress in borderline personality disorders is associated with hallucinations and suicidal ideation (10, 11).

Interpersonal threatening experiences play an important role in creating a sense of shame, making the person perceive themselves as socially weak, inferior, or incomplete in the eyes of others (12, 13). Shame-related feelings may be rooted in early negative shame experiences, such as being criticized by parents, being bullied by peers, being sexually or physically abused, or displaying negative traits to others (13-15). Shame has a significant effect on vulnerability to mental disorders such as depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety, paranoia, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, and personality disorders (16, 17). Research shows that shame is associated with suicide (16-20). Shame is also associated with early life experiences (21-24).

criticism is another variable that can mediate the relationship between early life experiences and suicidal ideation. Self-criticism is associated with a wide range of mental disorders. Previous research has shown that self-criticism is linked to depressive symptoms in clinical and non-clinical samples, in a way that correlates with more severe depressive symptoms (25, 26). Self-criticism is considered a predictor variable of suicide and is related to suicidal ideation (27, 28). Self-criticism is also associated with suicidal ideation (29-31).

Mahdavi Rad et al. (32) investigated the mediating role of shame and self-criticism in the relationship between attachment styles and the severity of depressive symptoms. The results of Mahdavi Rad et al. (32) showed that the anxious-avoidant insecure attachment path and the anxious-ambivalent insecure attachment path significantly influence the severity of depressive symptoms through the mediation of shame and self-criticism. In a study, Salarian Kaleji et al. (33) demonstrated that self-criticism and body image shame can mediate the relationship between early victimization experiences related to body image and the severity of binge eating symptoms in an Iranian sample.

Campos and Mesquita (34) investigated the pattern of suicide, which includes dependency, self-criticism, depression, anger-temperament, and anger (expressing anger toward oneself) in teenagers. Self-criticism, dependency, and anger-temperament play a role in predicting depression, which directly or indirectly predicts suicide through internal anger. Additionally, in a sample of depressed adults, increased self-criticism was associated with a greater likelihood of suicidal behaviors (27). The conceptual model of the research is shown in Figure 1.

Given the complex and multidimensional nature of early life experiences with suicidal ideation, the relationship between these variables does not appear to be linear and direct, as other variables may intervene in this relationship. A review of research findings also supports this view. This raises the question of whether the relationship between early life experiences and suicidal ideation is a simple and direct one or whether other psychological variables may also play a mediating role.

2. Objectives

In this study, we examine the mediating role of shame and self-criticism. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the mediating role of shame and self-criticism in the relationship between early life experiences and suicidal ideation in students.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects and Methods Sample

The design of the study was descriptive-correlational using structural equation modeling. The correlational research design allows the identification of possible cause-and-effect patterns in relation to psychiatric disorders, which can be used in future studies to plan clinical trials aimed at reducing psychiatric problems. The statistical population of this study included all students of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences during 2020 - 2021.

A crucial question in structural equation modeling is determining the minimum sample size required to collect data for this analysis. When structural equation modeling is used, approximately 20 samples are needed for each factor (latent variable) (35). Additionally, a sample size greater than 200 is recommended for effective structural equation modeling (36, 37). Among the statistical population of the study, 296 students participated using the available sampling method and completed the questionnaires.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Participants were required to be 18 years or older, enrolled as students, and willing to participate in the study. After receiving the code of ethics from the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences and obtaining participants' consent, the questionnaires were distributed. During the research, if any event occurred that violated the continuation of the study, cooperation with the volunteer was terminated. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage.

Participants were informed that all collected information would remain confidential. To increase the accuracy and motivation of the volunteers and to ensure the reliability of the responses, they were told that if they wished to know the results of the research, they could provide their email address to the researcher.

3.2. Measures

Self-criticizing/Attacking and Self-reassuring Scale-Short Form (FSCRS-SF): This scale is designed to assess how individuals think and react in the face of failure. It is a 14-item scale in which participants respond to items on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = not at all like me to 4 = quite like me). This scale demonstrates desirable psychometric properties (38). In Khanjani et al.'s study (39), the internal consistency was determined using Cronbach's alpha, which was calculated to be 0.87.

3.2.1. Beck Suicide Ideation Scale

This scale provides a numerical estimate of the intensity of ideation and suicidal ideation and consists of 19 items graded on a three-point scale from zero (lowest intensity) to 2 (maximum intensity) (40). In Iran, Anisi et al. reported the reliability of the scale with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.95 and a split-half reliability of 0.75 (41).

3.2.2. Early Life Experience Scale

This 15-item scale was developed by Gilbert et al. It examines the importance and value of assessing personal emotional behaviors and experiences from childhood. Participants rate items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (absolutely true of me) to 5 (completely false of me). This scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties (42). The Persian version of the scale was standardized by Khanjani et al. (43). The results showed that ELES is a reliable and valid tool with good internal consistency (0.74) and test-retest reliability (0.88). Regarding convergent validity, ELES showed a positive and significant correlation with difficulty in emotion regulation (r = 0.26) and borderline personality traits (r = 0.37). Additionally, it showed a significant negative relationship with compassion (r = 0.45), indicating favorable divergent validity.

3.2.3. The External and Internal Shame Scale

An eight-item scale is used to measure shame. Participants respond to each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from never (0) to always (4). This scale demonstrates desirable psychometric properties (44). Cronbach's alpha was used to assess the scale's reliability, with a total alpha of 0.89. The scale also showed good convergence with the self-criticism Scale and the shame Scale (44). Abousaedi Jirofti et al. (45) investigated the psychometric features of the Persian version. The results of confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the scale has a two-factor structure and exhibits good confirmatory validity. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.71 for internal shame, 0.78 for external shame, and 0.85 for the overall scale.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

In this study, mean, standard deviation, and Pearson correlation were analyzed using SPSS-23, while structural equation modeling was conducted using LISREL 10 software. Structural equation modeling was employed to investigate the research hypothesis. The model was evaluated using fit indices, including the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ²/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI), Relative Fit Index (RFI), and Incremental Fit Index (IFI).

Typically, an χ²/df ratio of less than 3 indicates a good model fit. An RMSEA coefficient below 0.08 and an SRMR value below 0.09 are also indicative of a good fit. Fit indices such as CFI, GFI, AGFI, IFI, RFI, NFI, and NNFI higher than 0.90, and AGFI higher than 0.85, suggest the acceptability of the structural equation model fit (46, 47). In the present study, the bootstrap test in SPSS-24 software was used to determine the significance of the mediating relationship in the main hypothesis of the research.

4. Results

4.1. Description of the Sample

Data from 296 people were analyzed. Among the participants, 147 (49.7%) were female, and 149 (50.3%) were male. The age range of the participants was 18 - 48 years, with a mean and standard deviation of 22.27 ± 5.64. A total of 215 (72.64%) participants were single, and 81 (27.36%) were married. Regarding the educational status of the 296 students who participated in this study: Seventy five (25.33%) had a Ph.D., 60 (20.27%) had a BSc degree, and 161 (54.39%) had an MSc degree.

The results in Table 1 show that suicidal ideation has a positive and significant relationship with shame (r = 0.43, P = 0.01), self-criticism (r = 0.30, P = 0.01), and early life experiences (r = 0.37, P = 0.01). Other research variables also have positive and significant relationships (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: BSSI, Beck Suicide Ideation Scale; FSCRS-SF, Self-criticizing/Attacking and Self-reassuring Scale-Short Form; ELES, Early Life Experience Scale; EISS, External and Internal Shame Scale.

a Correlation is significant at 0.01 level.

b Correlation is significant at 0.05 level.

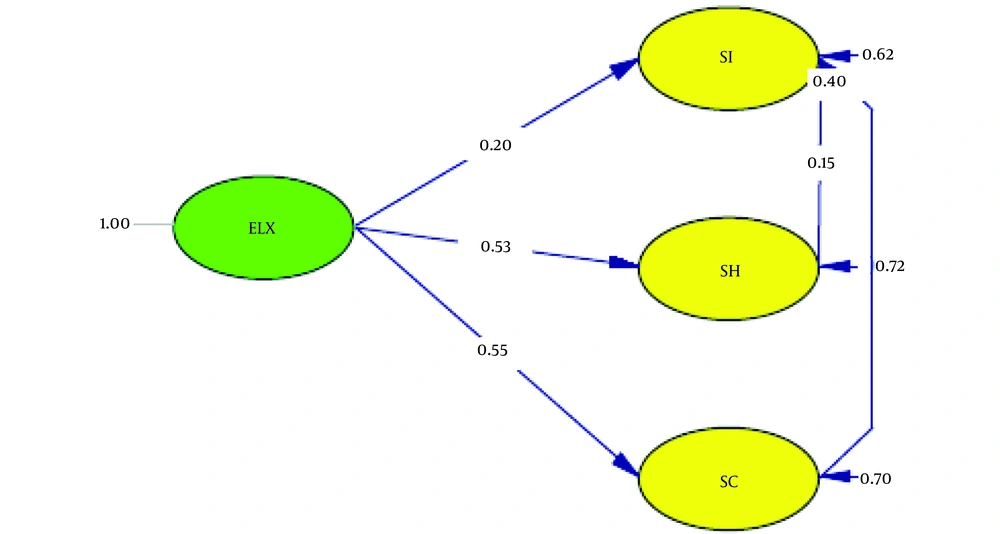

In the present study, the hypothetical model (Figure 1) examined the relationship between suicidal ideation and early life experiences mediated by shame and self-criticism. Initially, the assumptions for structural equation modeling, including the level of data for all interval variables, normality of the data, absence of outliers, linearity, and no multicollinearity, were investigated. All assumptions were met. The results of the proposed model's fit indices are presented in Table 2, indicating that the proposed model had a good fit.

| Indices | NNFI | NFI | GFI | RFI | IFI | CFI | χ2/df | df | χ2 | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 2.74 | 1479 | 4066.18 | 0.07 |

Abbreviations: NNFI, Non-normed Fit Index; NFI, Normed Fit Index; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; RFI, Relative Fit Index; IFI, Incremental Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; X2/df, ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

As shown in Figure 2, early life experiences had a direct effect (ß = 0.20, t = 2.47) on suicidal ideation, which is significant. Shame also had a direct effect (ß = 0.15, t = 2.11) on suicidal ideation, which is significant. Similarly, self-criticism had a direct effect (ß = 0.40, t = 3.09) on suicidal ideation, which is significant. In structural equation modeling, the significance of the path coefficient is determined using the t-value, and if the t-value is greater than 1.96, the relationship between the two constructs is considered significant.

In the present study, the bootstrapping test was used with 1,000 replications of the sample and a 95% confidence interval to evaluate the mediating relationship. According to this method, if the upper and lower limits of the percentage for the mediating path have the same sign (both positive or both negative), or if the value of zero does not fall between these two limits, the indirect causal path is considered significant.

As shown in Table 3, the results of the bootstrapping test revealed that the path from early life experiences to suicidal ideation mediated by shame, with a standard coefficient of 0.12 at the 0.05 significance level, is significant. Additionally, the results of the bootstrapping test indicated that the path from early life experiences to suicidal ideation mediated by self-criticism, with a standard coefficient of 0.03 at the 0.05 significance level, is significant.

| Independent Variables | Mediator Variables | Dependent Variables | Resamples | 95% CI | SE | Size Effect | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper | Lower | |||||||

| Early life experiences | Shame | Suicidal ideation | 1000 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Early life experiences | Self-criticism | Suicidal ideation | 1000 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

5. Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study to examine the mediating role of shame and self-criticism in the relationship between early life experiences and suicidal ideation. The results showed that shame and self-criticism significantly mediate the relationship between early life experiences and suicidal ideation. Sekowski et al. (24) examined the relationship between childhood maltreatment, depression, guilt, shame, and suicidal ideation in a sample of outpatients. The indirect effects of childhood maltreatment through self-conscious emotions on suicidal ideation were confirmed. Xavier et al. (48) showed that external shame, self-hatred, and fear of self-compassion indirectly lead to non-suicidal self-injury.

In a study, Ammerman and Brown (49) investigated the mediating role of self-criticism in the relationship between parents' emotional expressiveness and non-suicidal self-injury. A total of 294 teenagers and young adults completed the questionnaires. The results showed that self-criticism mediates the relationship between parents' emotional expressiveness and the occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury (49).

Xavier et al. investigated the mediating role of self-criticism and depression in the relationship between emotional experiences with parents and peers and self-injury. The results showed that negative experiences with parents and being victimized indirectly affect non-suicidal self-harm (50).

Explaining the results, it can be said that negative childhood experiences may cause shame in individuals. Shame creates a deep sense of inadequacy, weakness, and extreme humiliation, and individuals may turn to suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, or suicides to alleviate these intense feelings. Excessive use of shame as a disciplinary tool creates long-term problems in controlling children's emotions. Parents who constantly shame their children tend to raise children who are more anxious, fearful, and at greater risk for depression and anxiety. Consequently, depression increases the risk of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.

Early negative life experiences can lead to self-criticism in individuals. Self-critical people often fall into a vicious cycle where a low mood leads to self-criticism, and self-criticism further exacerbates the low mood. Welton and Greenberg (51) have shown that the pathological aspects of self-criticism are not only related to the content of thoughts but also to the effects of retroflection and the humiliation associated with criticism. Self-criticism can take the form of self-hatred. Self-hatred is often associated with a history of harassment and can result in harm to parts of the body. Early life events and experiences may lead to a failure to achieve one’s desires. This failure often results in self-blame and self-criticism. Individuals who engage in self-criticism may refuse to acknowledge their shortcomings in certain areas. In such cases, failure can create a profound sense of worthlessness. This absolute sense of worthlessness may lead to suicidal ideation in these individuals.

Research in behavioral sciences has certain limitations, and this study also faced limitations. Addressing these limitations in future research can help achieve more valid results. The limitations of the present study include being restricted to a student sample, the use of a convenience sampling method, and a correlational research design that cannot conclusively establish causality. These limitations may also affect the generalizability of the results. The sample was confined to university students, without excluding those who might have had mental disorders. Limitations associated with self-report tools include response bias, social desirability, and memory distortion. Emotional states such as depression or dissociative conditions may introduce memory bias or alterations, potentially impacting the accuracy of self-reported data. Social desirability, situational factors, poor recall, and errors in self-reporting could also influence the study’s findings.

It is suggested that experimental designs with more rigorous controls be employed to better understand the factors influencing the relationship between early life experiences and suicidal ideation. Additionally, it is recommended to investigate this relationship in clinical samples. This study provides foundational information for further interventional research on suicidal ideation among college students. Future findings based on these results could assist health managers in developing strategies to promote health among college students. It is also suggested that further research be conducted in clinical samples, such as individuals with borderline personality disorder.

5.1. Conclusions

Shame and self-criticism are significant variables in understanding the psychopathology of psychiatric disorders. Based on the results of this study, it can be concluded that early childhood experiences contribute to the development of shame and self-criticism, which are associated with the emergence of suicidal ideation. Therefore, shame and self-criticism should be considered in the development of therapeutic interventions aimed at addressing suicidal ideation.