1. Background

Despite advancements in cancer treatment, oral cancer remains one of the top 10 most prevalent cancers worldwide. This is primarily due to delayed diagnosis, as well as other factors such as being asymptomatic in the early stages, clinical resemblance to other lesions, and the diversity in clinical manifestations (1, 2). Oral cancer encompasses a group of neoplasms that can affect any area of the oral cavity, throat, and salivary glands, with an estimated 90% of all oral neoplasms being oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (1, 3).

From a clinical perspective, OSCC is typically characterized by a red and white lesion or a red lesion with a slightly rough surface and defined borders. In the early stages, these lesions are usually painless, but as the disease progresses, they may become uncomfortable and exhibit features such as ulcers, induration, and tissue changes, as well as signs of adhesion (4, 5). Ulceration is a common sign of OSCC, with the lesion having a hard base, irregular margins, and a firm texture when palpated (6, 7). The posterior lateral border of the tongue has the highest prevalence of OSCC, accounting for around 50% of cases (8). Additionally, bilateral lymph nodes, lungs, bones, and the liver are common sites for OSCC metastases (9).

A study from southern Iran has shown that out of 11,220 registered cancer cases, 200 cases of OSCC (1.7%) were reported (10). Also, the age-standardized incidence rate of oral cancer was 1.96 (95% CI: 1.65 - 2.26, Q statistic = 1118.09, df = 25, P < 0.0001, I² = 97.8%) for men and 1.46 for women (95% CI: 1.14 - 1.77, Q statistic = 2576.99, df = 26, P < .0001, I² = 99.0%) (11).

Data from Khuzestan province indicates an overall increase in the prevalence of oral and pharyngeal cancer, particularly among younger age groups and women during the study (1). The individual survival rate for those diagnosed with oral or throat cancer remains low, with only 50% of these individuals surviving after five years (five-year survival rate) (12).

From the patients' perspective, patients may prioritize quality of life over long-term survival. The main concern of the patient is the survival time and functional impairments resulting from surgery and adjuvant treatment. The success of treatment should be measured not only based on recurrence and metastasis but also on the characteristics that indicate quality of life. Therefore, during the treatment of patients with oral SCC, it is crucial to avoid severe functional and aesthetic disturbances (13, 14).

Patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancers can experience both acute and chronic side effects. These include changes in soft tissue as well as transient and permanent sensory disorders. Additionally, radiotherapy can worsen oral and periodontal health, as well as increase the risk of osteoradionecrosis. The short-term consequences of radiotherapy include acute effects such as mucositis, mucosal infections, pain, thick secretions, and sensory disturbances. However, the long-term chronic effects tend to be even more severe. These can manifest as tissue fibrosis, salivary gland dysfunction, heightened vulnerability to infections, neuropathic pain, persistent sensory disorders, and a higher incidence of dental caries and periodontal disease (15).

These side effects can be either acute or chronic and may vary from patient to patient, depending on factors such as the cancer stage, location, and the specific treatment modalities utilized. These treatment-related side effects can have a significant impact on the patient's overall survival and various aspects of their quality of life, including function, speech, taste, mouth dryness, oral infections, dental decay, bone necrosis, and nutrition (16).

Ghorbani et al. conducted research to assess the quality of life related to oral health in patients with OSCC. Findings had shown that the mean OHIP score in the patient group was 22.84 ± 11.42, as compared with the control group 17.92 ± 9.23 (P = 0.005). Of the available treatment modalities, surgery had the least impact on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). In contrast, the combination treatment approach involving surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy resulted in the greatest reduction in OHRQoL (17).

In recent years, there has been growing research focused on the quality of life for patients, with the evaluation of OHRQoL now recognized as a critical component of patient care. Despite the numerous effects and symptoms experienced by patients with OSCC, stemming from both the disease itself and its treatment, information on the OHRQoL of this patient population remains limited.

2. Objectives

We aimed to assess the OHRQoL in patients diagnosed with OSCC in Ahvaz city in Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Patients

This was a cross-sectional study that assessed the OHRQoL in patients with OSCC at the population-based cancer registry center in Ahvaz city, which serves as a public cancer center in the southwest region of Iran. Time and funding limitations, as well as incomplete patient records, necessitated a cross-sectional study design.

As the number of OSCC patients in the Khuzestan cancer registry system was limited, a census method was used to include all willing participants in the study. The researcher then contacted the individuals, obtained their informed consent, and explained the objectives of the research. The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of OSCC and willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included unwillingness to continue with the research and incomplete questionnaires.

Data collection was carried out using questionnaires in two sections: The first section focused on demographic characteristics, and the second section utilized the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14) Questionnaire. The researcher administered the questionnaires, and participants chose the most fitting response in the form of face-to-face interviews. Thus, there was no missing data in the completed questionnaires.

The researcher explained the study's purpose, procedures, and ethical considerations to participants and obtained their written consent. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences with ethics code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1402.202.

3.2. Questionnaire

The first section collected demographic information, including age, gender, marital status, education level, income category, employment status, household composition, comorbidities, race, dental caries, and dental restorations.

The OHIP-14 Questionnaire was used to assess the participants' OHRQoL. This questionnaire was first developed by Slade in 1997 to examine seven aspects of OHRQoL. According to a study by Motallebnejad et al. (18), this questionnaire has demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability, and it has been widely used in research studies conducted in Iran (Cronbach's alpha = 0.095).

The OHIP-14 Questionnaire consists of seven subscales: (1) Functional limitation, (2) physical pain, (3) psychological discomfort, (4) physical disability, (5) psychological disability, (6) social disability, (7) handicap, each subscale includes two questions. The responses were evaluated using the additive (ADD) method, where the response options were scored as: Never = 0, rarely = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3, always = 4; In this method, the OHIP-14 score ranges from 0 to 56, with lower scores indicating a better quality of life for the subjects. The overall oral health score is generally calculated between 14 and 70, where a lower score indicates a higher OHRQoL (19).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical pattern (normality of error distribution) was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics were presented employing frequency and percentages or mean and standard deviation, as appropriate for continuous parameters.

Analytical statistics included the Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA), and the significance level was considered less than 0.05 for all analyses.

4. Results

A total of 85 subjects were enrolled. Among them, 47 (55.3%) patients were male, and the remainder were female. Illiterate patients comprised 32 (37.6%), while the rest had education levels ranging from elementary to diploma and university education. Most of the subjects were Arab, accounting for 45 (52.9%) of the participants. Other demographic and background variables are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| < 55 | 32 (37.6) |

| > 55 | 53 (62.4) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 47 (55.3) |

| Female | 38 (44.7) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 32 (37.6) |

| Elementary to diploma | 31 (36.5) |

| University | 22 (25.9) |

| Family households | |

| 1 - 5 | 73 (85.9) |

| 6 - 10 | 12 (14.1) |

| Job status | |

| Employed | 22 (25.9) |

| Unemployed | 46 (54.1) |

| Retired | 17 (20) |

| Insurance status | |

| Public insurance | 42 (49.4) |

| Others insurance | 34 (40) |

| No insurance | 9 (10.6) |

| Income status | |

| Low | 23 (25.9) |

| Moderate | 40 (47.1) |

| High | 22 (27.1) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Yes | 56 (65.9) |

| No | 29 (34.1) |

| Race | |

| Arab | 45 (52.9) |

| Bakhtiary | 20 (23.5) |

| Others | 20 (23.5) |

| Dental decay | |

| Yes | 18 (21.1) |

| No | 67 (78.8) |

| Dental restoration | |

| Yes | 26 (30.6) |

| No | 59 (69.4) |

Data in Table 2 demonstrated the mean ± SD of OHRQoL and its dimensions. The mean score of OHRQoL in patients with OSCC in Ahvaz was 31.45 ± 6.15, indicating that their OHRQoL is moderate. The highest mean score for OHRQoL dimensions was attributed to physical disability (5.02 ± 1.57), while psychological disability had the lowest score (4.08 ± 1.30).

| Variables | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Functional limitation | 4.22 ± 1.78 |

| Physical pain | 4.69 ± 1.83 |

| Psychological discomfort | 4.80 ± 1.74 |

| Physical disability | 5.02 ± 1.57 |

| Psychological disability | 4.08 ± 1.30 |

| Social disability | 4.40 ± 1.49 |

| Handicap | 4.23 ± 1.50 |

| OHRQOL | 31.45 ± 6.15 |

Abbreviation: OHRQOL, oral health-related quality of life.

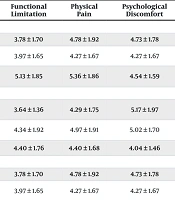

Based on the results of Tables 3 and 4, there was no significant difference between the mean score of OHIP-14 and its dimensions based on gender, household size, and race. However, some variables showed significant differences in certain dimensions of OHRQoL. A significant correlation was found between the mean score of functional limitations and marital status, decayed teeth, dental restoration, and income (P < 0.05). Moreover, a significant correlation was observed between the mean score of psychological disability and education, job, and insurance types (P < 0.05). Additionally, Handicap was significantly higher among single individuals compared to married individuals (P < 0.05).

| Variables | Functional Limitation | Physical Pain | Psychological Discomfort | Physical Disability | Psychological Disability | Social Disability | Handicap | OHRQOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| < 55 | 4.81 ± 1.86 | 5.12 ± 1.91 | 4.84 ± 1.66 | 5.06 ± 1.41 | 4.24 ± 1.52 | 4.21 ± 1.47 | 4.15 ± 1.58 | 32.45 ± 5.51 |

| > 55 | 3.84 ± 1.64 | 4.42 ± 1.74 | 4.76 ± 1.81 | 5.00 ± 1.68 | 3.98 ± 1.14 | 4.51 ± 1.51 | 4.28 ± 1.47 | 30.82 ± 6.49 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 4.81 ± 1.86 | 5.12 ± 1.91 | 4.84 ± 1.66 | 5.06 ± 1.41 | 4.24 ± 1.52 | 4.21 ± 1.47 | 4.15 ± 1.58 | 32.45 ± 5.51 |

| Female | 3.84 ± 1.64 | 4.42 ± 1.74 | 4.76 ± 1.81 | 5.00 ± 1.68 | 3.98 ± 1.14 | 4.51 ± 1.51 | 4.28 ± 1.47 | 30.82 ± 6.49 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 4.81 ± 1.86 | 5.12 ± 1.91 | 4.84 ± 1.66 | 5.06 ± 1.41 | 4.24 ± 1.52 | 4.21 ± 1.47 | 4.15 ± 1.58 | 32.45 ± 5.51 |

| Married | 3.84 ± 1.64 b | 4.42 ± 1.74 | 4.76 ± 1.81 | 5.00 ± 1.68 | 3.98 ± 1.14 | 4.51 ± 1.51 | 4.28 ± 1.47 | 30.82 ± 6.49 |

| Family household | ||||||||

| < 5 | 4.27 ± 1.86 | 4.82 ± 1.87 | 4.87 ± 1.80 | 5.01 ± 1.65 | 4.05 ± 1.24 | 4.39 ± 1.56 | 4.24 ± 1.52 | 31.68 ± 6.40 |

| > 5 | 3.91 ± 1.24 | 3.91 ± 1.37 | 4.33 ± 1.30 | 5.08 ± 0.99 | 4.25 ± 1.65 | 4.41 ± 1.08 | 4.16 ± 1.46 | 30.08 ± 4.29 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.94 ± 1.61 | 4.96 ± 1.79 | 4.94 ± 1.87 | 5.12 ± 1.44 | 4.03 ± 1.17 | 4.42 ± 1.52 | 4.03 ± 1.51 | 31.48 ± 6.22 |

| No | 4.75 ± 2.01 | 4.17 ± 1.81 | 4.51 ± 1.45 | 5.12 ± 1.44 | 4.17 ± 1.53 | 4.34 ± 1.47 | 4.62 ± 1.44 b | 31.41 ± 6.11 |

| Dental restoration | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.84 ± 1.60 | 4.61 ± 1.70 | 4.61 ± 1.70 | 4.91 ± 1.54 | 4.15 ± 1.28 | 4.38 ± 1.48 | 4.13 ± 1.54 | 31.05 ± 6.08 |

| No | 5.07 ± 1.91 b | 4.88 ± 2.12 | 4.88 ± 2.12 | 5.26 ± 1.63 | 3.92 ± 1.35 | 4.42 ± 1.55 | 4.46 ± 1.42 | 32.38 ± 6.31 |

| Dental decay | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.79 ± 1.54 | 4.68 ± 1.76 | 4.94 ± 1.79 | 4.86 ± 1.51 | 4.00 ± 1.26 | 4.46 ± 1.42 | 4.14 ± 1.48 | 30.89 ± 5.77 |

| No | 5.83 ± 1.75 b | 4.72 ± 2.10 | 4.27 ± 1.44 | 5.61 ± 1.68 | 4.38 ± 1.41 | 4.16 ± 1.75 | 4.55 ± 1.58 | 33.55 ± 7.19 |

Abbreviation: OHRQOL, oral health-related quality of life.

a Mann-Whitney U test.

b P-value < 0.05.

| Variables | Functional Limitation | Physical Pain | Psychological Discomfort | Physical Disability | Psychological Disability | Social Disability | Handicap | OHRQOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | ||||||||

| Illiterate | 3.78 ± 1.70 | 4.78 ± 1.92 | 4.73 ± 1.78 | 5.17 ± 1.37 | 4.34 ± 1.64 | 4.39 ± 1.46 | 3.91 ± 1.53 | 31.13 ± 5.64 |

| Elementary to diploma | 3.97 ± 1.65 | 4.27 ± 1.67 | 4.27 ± 1.67 | 4.70 ± 1.65 | 3.95 ± 1.10 | 4.35 ± 1.45 | 4.27 ± 1.50 | 30.50 ± 6.11 |

| University | 5.13 ± 1.85 | 5.36 ± 1.86 | 4.54 ± 1.59 | 5.45 ± 1.56 | 4.04 ± 1.25 b | 4.50 ± 1.65 | 4.50 ± 1.50 | 33.54 ± 6.49 |

| Job status | ||||||||

| Employed | 3.64 ± 1.36 | 4.29 ± 1.75 | 5.17 ± 1.97 | 4.35 ± 1.41 | 3.35 ± 0.996 | 4.11 ± 1.61 | 4.00 ± 1.45 | 28.94 ± 6.69 |

| Unemployed | 4.34 ± 1.92 | 4.97 ± 1.91 | 5.02 ± 1.70 | 4.04 ± 1.78 | 4.26 ± 1.28 | 4.39 ± 1.54 | 4.08 ± 1.61 | 32.34 ± 6.24 |

| Retired | 4.40 ± 1.76 | 4.40 ± 1.68 | 4.04 ± 1.46 | 5.04 ± 1.78 | 4.27 ± 1.38 b | 4.63 ± 1.32 | 4.72 ± 1.24 | 31.54 ± 5.17 |

| Income status | ||||||||

| Low | 3.78 ± 1.70 | 4.78 ± 1.92 | 4.73 ± 1.78 | 5.17 ± 1.37 | 4.34 ± 1.64 | 4.39 ± 1.46 | 3.91 ± 1.53 | 31.13 ± 5.64 |

| Moderate | 3.97 ± 1.65 | 4.27 ± 1.67 | 4.27 ± 1.67 | 4.70 ± 1.65 | 3.95 ± 1.10 | 4.35 ± 1.45 | 4.27 ± 1.50 | 30.50 ± 6.11 |

| High | 5.13 ± 1.85 b | 5.36 ± 1.86 | 4.54 ± 1.59 | 5.45 ± 1.56 | 4.04 ± 1.25 | 4.50 ± 1.65 | 4.50 ± 1.50 | 33.54 ± 6.49 |

| Insurance status | ||||||||

| Public insurance | 3.90 ± 1.46 | 4.61 ± 1.80 | 4.73 ± 1.83 | 4.83 ± 1.49 | 3.71 ± 1.31 | 4.35 ± 1.57 | 3.88 ± 1.38 | 30.04 ± 5.81 |

| Others insurance | 4.73 ± 2.01 | 4.76 ± 1.93 | 4.79 ± 1.62 | 5.14 ± 1.55 | 4.41 ± 1.18 | 4.35 ± 1.49 | 4.61 ± 1.57 | 32.82 ± 6.19 |

| No insurance | 3.77 ± 1.98 | 4.77 ± 1.71 | 5.11 ± 1.90 | 5.44 ± 2.00 | 4.55 ± 1.33 b | 4.77 ± 1.20 | 4.44 ± 1.58 | 32.88 ± 6.73 |

| Race | ||||||||

| Bakhtiary | 4.55 ± 1.98 | 5.30 ± 2.07 | 4.85 ± 1.34 | 5.05 ± 1.73 | 4.25 ± 1.06 | 4.10 ± 1.48 | 3.75 ± 1.48 | 31.85 ± 4.53 |

| Arab | 4.06 ± 1.52 | 4.71 ± 1.57 | 4.84 ± 1.84 | 5.08 ± 1.51 | 4.17 ± 1.15 | 4.73 ± 1.30 | 4.42 ± 1.42 | 32.04 ± 5.83 |

| Others | 4.25 ± 2.14 | 4.05 ± 1.98 | 4.65 ± 1.92 | 4.85 ± 1.59 | 3.70 ± 1.75 | 3.95 ± 1.79 | 4.30 ± 1.68 | 29.75 ± 7.98 |

Abbreviation: OHRQOL, oral health-related quality of life.

a Kruskal wallis test.

b P-value < 0.05.

5. Discussion

The present study is the second scientific paper on OHRQoL in patients with OSCC in Iran and the first scientific report related to OHRQoL in patients with OSCC in Khuzestan. The results of this study demonstrate that OHRQoL and dental health in patients with OSCC are moderate. Additionally, the data show that there is no statistically significant relationship between the total score of OHRQoL and all demographic variables, including age, gender, marital status, race, family size, employment status, economic status, insurance status, educational levels, background diseases, and history of decayed and restored teeth. However, some variables showed significant differences in certain dimensions of OHRQoL. We offer possible reasons for these results and explore their potential implications for clinical application.

In this study, the mean score of OHRQoL was 6.15 ± 31.45. In a case-control study conducted by Ghorbani et al., the results revealed that the mean OHIP score was 22.84 ± 11.42 in the patient group and 17.92 ± 9.23 in the control group, showing a significant difference (P = 0.005) between the two groups based on the independent sample t-test (20).

Gondivkar et al. conducted a study aimed at investigating the HRQoL and OHRQoL in OSCC patients treated with various modalities. The findings indicated that patients who received postoperative chemoradiotherapy (PCRT) had significantly higher mean subscale and overall OHIP-14 scores (24.57 ± 2.62) compared to those treated with surgery alone (10.55 ± 2.26) or preoperative radiotherapy (PRT) (20.20 ± 3.80) (P < 0.001). However, the OHRQoL was significantly compromised in all three study groups (P < 0.001) (21).

In another study, the mean OHIP-14 score of patients diagnosed with OSCC was reported as 22.92, with the dimension of physical pain being the most affected (22).

Also, the mean score of OHRQoL in a study on breast cancer patients (23), head and neck cancer patients (24), and bladder cancer patients (25) was 10.29 ± 12.80, 10.11 ± 21.4, 2.39 ± 9.47, and 1.35 ± 11.48, respectively. Since the OHIP-14 test was used in all of these studies, it seems that this difference may be due to the fact that chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments primarily target the oral cavity in patients with OSCC, while in other cancers, oral tissue is not considered the main target of treatment, and the side effects of treatments may appear only partially in the mouth.

Therefore, the OHRQoL is predictably worse in patients with oral cancer. Accordingly, it seems that clinicians should provide comprehensive oral health care, including regular dental check-ups, cleanings, and treatments, to manage any complications and improve overall oral health.

This study demonstrated that there is no association between OHRQoL and gender. This finding is consistent with the results of the Ribas-Perez et al.’s study, which examined the relationship between gender and OHRQoL in immigrant children in Spain using the OHIP-14 Questionnaire (26).

In contrast, studies conducted among Chinese college students showed that females scored significantly higher than males in the overall score, as well as in terms of physical pain (P < 0.001), physical disability (P < 0.001), and psychological disability (P < 0.001) (27). Some findings from previous studies suggest that gender-specific strategies have the potential to improve oral health, such as the observation that women are more likely to adhere to recommended dental treatment after examination (28). Additionally, other research indicates that females demonstrate more positive attitudes towards dental visits, oral health literacy, and dental self-care behaviors compared to males (29, 30).

It is possible that psychosocial factors, such as coping mechanisms, social support, and cultural norms, may influence how male and female patients with OSCC perceive and report their OHRQoL. These factors could potentially outweigh any direct biological differences between genders.

Overall, the finding that gender is not associated with OHRQoL in patients with OSCC underscores the importance of personalized and patient-centered care approaches to optimize outcomes and enhance the overall quality of life for individuals affected by this condition.

Our study found that the presence or absence of decayed teeth and restored teeth did not have a significant association with the overall score of OHRQoL. However, the absence of decayed teeth and restored teeth was associated with better outcomes in the functional limitation domain. This finding is consistent with a previous study that used the Child Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (CPQ11-14) to examine children, which also showed a relationship between the presence of decayed teeth and functional limitations (31).

Additionally, another study conducted on adolescents in central urban areas of Brazil found a significant correlation between the decay component and all dimensions of the OHIP-14 Questionnaire (32). In contrast to the findings of the present study, a separate study on patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed a significant correlation between the overall OHIP-14 score and the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) Index (33). Conversely, a study conducted on bladder cancer patients in Ahvaz found no association between the DMFT Index and OHRQoL.

Overall, given the severity of oral complications experienced by patients with oral cancer, as well as the adverse effects resulting from chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the DMFT status alone may not be a significant determinant of OHRQoL in this patient population. Oral health-related quality of life is influenced by a variety of factors, including physical, psychological, and social aspects of oral health. The presence or absence of decayed or restored teeth may be only one of many factors contributing to OHRQoL, with other variables, such as oral cancer treatment, likely having a stronger influence on the overall score.

In the present study, it was demonstrated that although having public insurance does not show an association with the total score of OHRQoL in cancer patients, insurance status can influence psychological disability, with individuals having public insurance showing better psychological disability status.

In the study by Brennan and Spencer (34), it was shown that patients with higher insurance coverage are more likely to seek dental care for non-pain-related issues. A possible reason for the current finding is that public insurance in Iran does not cover dental services, so having or not having insurance may not significantly affect the overall quality of life related to oral health.

However, in this study, having public insurance, while not improving the total OHRQoL score, was linked to better scores in psychological disability. This could be attributed to the peace of mind and assurance that individuals with insurance experience when facing medical issues, providing them with a sense of security and reduced psychological burden.

In the present study, it was shown that although different levels of education in oral cancer patients do not show an association with overall OHRQoL, individuals with oral cancer who had elementary to diploma education demonstrated better status in handicap compared to those with university education and those who were illiterate.

In a study conducted by Almoznino et al., it was found that people with different educational levels did not have significant differences in overall OHRQoL. However, individuals with university education showed better status in psychological disability compared to those with elementary to diploma education (35). In contrast to the findings of the present study, another research in Indonesia indicated that different educational levels can be related to the overall score of OHIP-14.

A possible explanation for the differences observed in these studies lies in the type of target group and their specific conditions. In the current study, education was only able to influence certain dimensions of OHRQoL, such as functional limitation, sense of taste, and pronunciation of words. However, due to the importance of other conditions and complications of the disease, education was not sufficient to improve the overall quality of life.

This finding is particularly interesting given that an individual's educational level is often reflective of their broader social status throughout life. Lower educational attainment can result in poorer job prospects, reduced social standing, and higher disease incidence. The relationship between educational status and OHRQoL underscores the significance of social determinants of health (25).

Despite these broader trends, in this study, university education appeared to only reduce difficulties in pronouncing words and disturbances in the sense of taste in patients with oral cancer. Further research is needed to explore the possible underlying causes of these findings.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine OHRQoL in patients with OSCC. However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations of the study.

Firstly, selection bias is inherently difficult to avoid when utilizing research registries, and this factor should be taken into account when interpreting the results. Secondly, since participants were only recruited from a single cancer registry, the generalizability of the findings should be approached with caution. Thirdly, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships. Conducting longitudinal studies would be beneficial to better understand the causal relationships between the predictors investigated and OHRQoL.

The study highlights the need for these factors to be considered when planning oral health intervention programs, particularly for the elderly and other vulnerable populations.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the findings of the present study, the OHRQoL in patients with OSCC was moderate. This highlights the importance of developing public health policies that prioritize preventive dental interventions for individuals with this condition, aiming to improve their overall oral and dental health.

Furthermore, since none of the demographic variables were found to significantly impact the total OHRQoL score, efforts should focus on identifying the key factors that effectively influence and enhance the quality of life in this patient population. This can provide decision-makers and policymakers with valuable information for evidence-based planning to improve patients' oral health.

Additionally, the study underscores the need to consider these factors when designing oral health intervention programs, particularly for the elderly and other vulnerable groups.