1. Background

Reports on burns in developing nations show a treatment issue accounting for five percent of hospital admissions (1). Research indicates that every year, 1.1 million burn patients receive treatment in the USA, while Europe treats 1 million burn patients (2). The occurrence of burns and the rate of deaths caused by burns are also elevated in Iran (3). According to Nischwitz et al. (4), burns rank as the fourth most common unexpected event worldwide, after road accidents, falls, and personal conflicts. The World Health Organization reports that over 300,000 people die from burns and their complications yearly, with over 95% of these deaths occurring in low and middle-income countries (5). Various psychological issues have been reported among burn victims, such as acute stress disorder, body image dissatisfaction, anxiety, life dissatisfaction, and the prevalence of negative emotions, sleep disturbances, and nightmares (6). The cognitive emotive theory suggests that stressful situations are mainly a subjective experience, influenced by how an individual perceives and evaluates potential threats in their environment, which can diminish one's overall life satisfaction (7). Many people confuse life satisfaction with freedom. A person who feels happy might believe they have complete freedom. Life satisfaction refers to a positive outlook on one’s feelings and thoughts about life. It also includes aspects like well-being, financial success, contentment, and optimism (8). Life satisfaction is actually based on a person’s desires and current situation. The larger the disparity between someone’s wishes and reality, the lower their satisfaction level.

In a lengthy study conducted in Australia, Bussing et al. (9) found a strong link between life satisfaction and feelings of happiness, optimism, and well-being. Human temperament has two types of moods: Positive excitement, which is energetic and enthusiastic, and negative excitement, which includes irritation and dissatisfaction. Both positive and negative emotions can influence how optimism and social adaptation relate to life satisfaction, affecting these connections (10). Research conducted by Seligman (11) revealed that experiencing positive emotions can enhance people’s ability to handle challenging tasks and boost feelings of optimism. Additionally, Davies et al. (12) stated that feeling positive excitement can serve as a psychological defense mechanism and help with problem-solving processes and positive perception. Therefore, enthusiasm plays a key part in forming people’s optimism. According to Garcia-Vazquez et al. (13), optimism is a positive view of current and future events that many people share. However, how optimism is expressed can change depending on individual situations and social environments, resulting in different outcomes. Optimism is thought to be influenced by both personal traits and the social environment of an individual (14). Based on research by Seligman (11), optimism is how people understand their achievements and mistakes. Positive individuals attribute their successes to internal, lasting, and broad reasons. In contrast, they blame outside, temporary, and specific reasons for their failures. According to Seligman (11), having a pessimistic mindset can ultimately lead to the individual experiencing distress and developing depression and physical health issues. Mehta et al. (5) and James et al. (6) both confirm the presence of anxiety caused by common burn complications, leading to various adverse psychological outcomes. Currently, to avoid further psychological issues, it is necessary to provide psychological treatments for individuals.

The Lyubomirsky happiness training program serves as a way to intervene. According to Lyubomirsky et al. (15), happiness is seen as a balance of positive and negative feelings over time, defined as joy, optimism, and a sense of life’s worth. It is a personal experience. Positive emotions improve skills, while depression reduces attention and abilities (16). Previous research revealed that Lyubomirsky happiness training enhanced life satisfaction, positive emotions, and optimism, and declined negative emotions and pessimism (17-20).

2. Objectives

The study examined how the Lyubomirsky happiness training program affected burn patients’ life satisfaction, emotions, and optimism at the Imam Musa Kazem Training Therapeutic Center. It focused on the program’s known benefits for enhancing individuals’ psychological well-being and character traits.

3. Methods

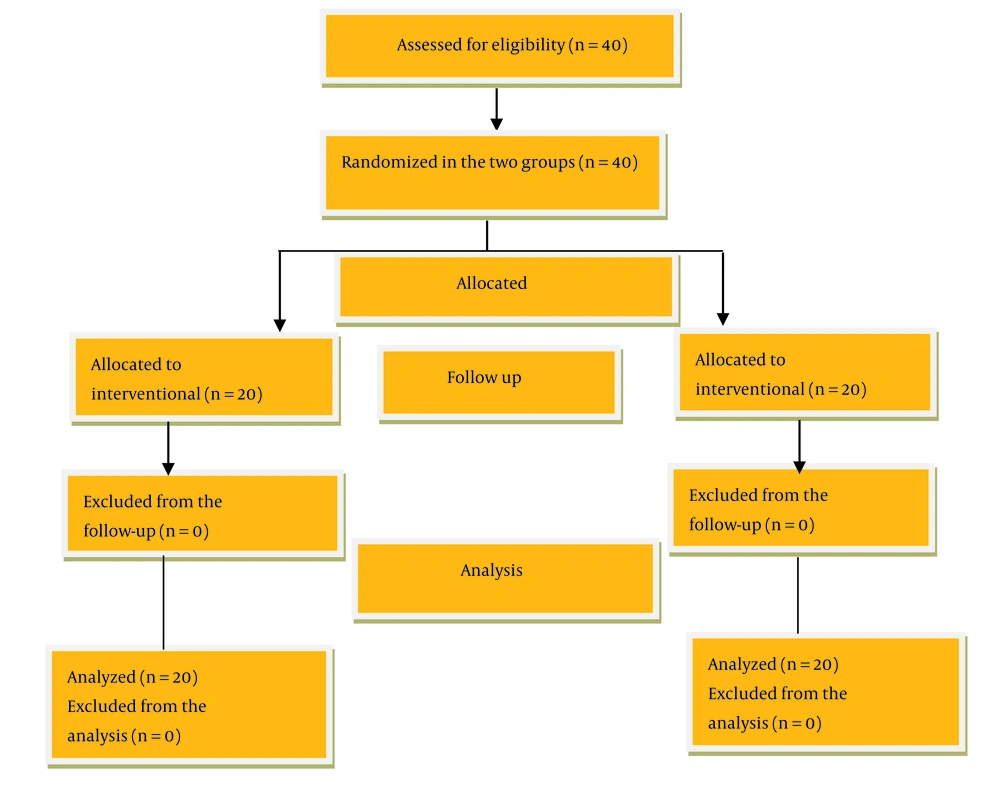

The present study was a randomized controlled trial with two parallel groups (one intervention group and one control group) with IRCT ID: IRCT20250117064408N1, conducted in a single-blind manner at the Imam Musa Kazem Training Therapeutic Center in Isfahan, Iran, from September 2022 to March 2023. The sample group consisted of burn patients comprising 10% to 60% of the total population in Isfahan city. To select burn victims, individuals meeting the research criteria (burn severity between 10% to 60%, possessing a minimum of a high school diploma, aged between 17 to 58 years old with a mean age of 32.78 and SD = 10.78) who visited the Imam Musa Kazem Training Therapeutic Center in Isfahan were picked using the convenience sampling method in the first stage. They were then randomly assigned into two groups: The experimental group (20 patients with a mean age of 31.85 and SD = 8.60) and the control group (20 patients with a mean age of 33.70 and SD = 12.75) in the second stage of the sampling method. Participants were divided into two groups, control and intervention, using a random method. In this study evaluating the effects of the Lyubomirsky happiness training Program on life satisfaction, emotions, and optimism in burn patients, each of the 20 participants was given a number from 1 to 20 using a random number generator. They were subsequently assigned, with all odd numbers to the intervention group and even numbers to the control group (Figure 1).

The sample size was calculated according to the results of a previous study, which reported that the mean score of well-being was 80.70 ± 6.47 in the intervention group and 71.13 ± 8.32 in the control group (21). Accordingly, with a confidence level and a power of 0.95, the sample size was determined to be 16 participants per group. However, 20 participants were chosen in each group to compensate for probable withdrawals and improve the power of the study.

The experimental group participated in six sessions of happiness training following Lyubomirsky’s approach, while the control group received the routine program. One requirement for inclusion was having burn severity ranging from 10% to 60%, holding at least a high school diploma, and being within the age range of 17 to 58 years, with an average age of 32.78 years and a standard deviation of 10.78. Exclusion criteria involved: (1) Patients who were undergoing pharmacological or psychiatric treatment; (2) patients who had both physical and mental illnesses; (3) patients who were suffering from substance abuse; and (4) patients who had a history of receiving psychological treatment. The study involved randomly assigning participants to either an experimental group or a control group. Both groups completed a pre-test on life satisfaction and emotions. The experimental group then underwent six happiness training sessions over 1.5 months, led by a trained psychologist, while the control group received the routine program. After the training, both groups took a post-test. A double-blind method was used to keep the study unbiased, so neither participants nor caregivers were informed, preventing expectations from affecting results (Table 1).

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| First | The pre-test involves getting to know group members and starting communication. It measures happiness and explains why focusing on happiness matters. The group will create motivation and agree to follow through on tasks. They will learn to act like happy people, engage in exercises, and complete assignments. |

| Second | The text talks about showing gratitude and appreciation through kindness and better communication. It suggests activities like sharing homework, being more hospitable, joining groups, listing blessings, and writing a thank-you letter. The letter should invite the recipient to the next workshop meeting. |

| Third | Discussing the importance of gratitude and reading letters written for guests, teaching optimism techniques, positivity, as well as teaching techniques to avoid mental rumination and social comparison, and trying to interpret everyday events in a positive way. |

| Fourth | The text discusses ways to enhance enjoyment of the present moment. It suggests techniques like going for walks, appreciating nature, focusing on beauty around you, savoring food, engaging in communication with your spouse, and adding variety to your environment. |

| Fifth | Teaching strategies and techniques of forgiveness and coping with stress, presenting a task to forgive others’ mistakes, practicing mental relaxation training. |

| Sixth | Training on choosing appropriate goals (long-term, short-term, and sub-goals) and commitment to follow them, providing solutions for dealing with religion and spirituality, meditation training and post-test implementation. |

3.1. Ethical Considerations

The guidelines of the APA and Helsinki Convention were adhered to in this research, and approval was received from the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1399.1160).

3.2. Research Tools

3.2.1. Life Satisfaction Questionnaire

Diener, et al. (22) created this questionnaire to assess life satisfaction. It includes 5 questions, each with 7 statements rated from one (completely disagree) to seven (completely agree). The scoring of this scale ranges from 5 to 35. The questionnaire’s threshold for determining a medium level of life satisfaction is between 20 and 24. Diener, et al. (22) found that the questionnaire had a validity of 0.62 and a reliability of 0.85. In Iran, the Life Satisfaction Scale showed good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83. Test-retest after one month yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.70. Validity was supported by a strong correlation of 0.71 with the Oxford Happiness Inventory and a negative correlation of -0.597 with the Beck Depression Inventory (23). In the current research, the questionnaire’s reliability using Cronbach's alpha was 0.87.

3.2.2. Optimism/Pessimism Questionnaire

Carver et al. (24) created the optimism survey to measure individuals’ levels of optimism/pessimism. The survey consists of 10 questions provided in a response set with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). The scores of this questionnaire range from 10 to 50. This questionnaire is divided into two parts evaluating positivity (3 questions) and negativity (3 questions), with 4 extra questions that are not part of the main score. Scheier and Carver (25) found that the questionnaire had a validity rate of 0.67 and a reliability of 0.86. In Iran, the concurrent validity coefficient between the Optimism Scale with depression and mastery was 0.64 and 0.72 (26). In this study, the reliability was equal to 0.84.

3.2.3. Positive and Negative Emotions Questionnaire

Watson and Clark (27) developed a questionnaire to measure both positive and negative emotions. This questionnaire consists of 20 questions presented in a response format, using Likert 5-point scale items (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree). The scoring of this questionnaire ranges from 20 to 100. This survey includes two sets of questions — one focusing on positive emotions and the other on negative emotions, with each set containing 10 questions. Watson and Clark (27) found a validity of 0.74 and a reliability of 0.80. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.89. In Iran, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported from 0.83 to 0.91, and in the normal sample from 0.85 to 0.90 (28). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

3.3. Statistical Methods

The data were analyzed using independent samples t-test, paired samples t-test, and one-way ANCOVA. All analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS version 22, and the significance level of alpha was set at 0.05.

4. Results

The study examined demographics such as age, gender, marital status, and burn percentage. It also evaluated factors like life satisfaction, emotions, and optimism in both the intervention and control groups, with results presented in the tables below.

The study included 40 burn patients aged 17 to 58, mostly between 26 and 35 years old, with an equal number in the control and intervention groups. The participants were primarily male, with 53.8% in the control group and 46.2% in the intervention group. Most of the patients were married. A larger proportion had a burn grade of 36 - 45%, with 77.8% in the control group and 22.2% in the intervention group. In Table 2, the study compared the control and intervention groups by age, sex, and marital status. The results showed no significant differences in age (P = 0.276), sex (P = 0.507), or marital status (P = 0.225). However, there was a significant difference in burn percentage grade between the two groups (P = 0.019).

| Variables and Groups | Control | Intervention | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 0.276 | ||

| 17 - 25 | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | |

| 26 - 35 | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | |

| 36 - 45 | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | |

| 46 - 58 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Sex | 0.507 | ||

| Male | 14 (53.8) | 12 (46.2) | |

| Female | 6 (42.9) | 8 (57.1) | |

| Marital status | 0.225 | ||

| Married | 13 (52.0) | 12 (48.0) | |

| Single | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | |

| Divorced | 2 (100.0) | 0 (00.0) | |

| Burning percentage | 0.019 | ||

| 15 - 25 | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | |

| 26 - 35 | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| 36 - 45 | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | |

| 46 - 60 | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Chi-square test.

The results of the independent t-test showed that there was no significant difference in the mean scores of life satisfaction (P = 0.44), positive emotions (P = 0.603), negative emotions (P = 0.627), and optimism (P = 0.126) between the control and intervention groups before the intervention. The results of ANCOVA revealed that the mean scores of life satisfaction (P = 0.003), positive emotions (P = 0.001), negative emotions (P = 0.001), and optimism (P = 0.001) after the intervention showed a significant difference between the control and intervention groups, with higher scores in the intervention group. The results of the paired t-test revealed that the changes in life satisfaction scores were significant between the control and intervention groups, with a greater increase observed in the intervention group compared to the control group (Table 3).

| Outcomes and Groups | Time | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | ||

| Life satisfaction | |||

| Control | 15.55 ± 7.26 | 17.40 ± 7.79 | 0.031 a |

| Intervention | 14.75 ± 7.29 | 19.95 ± 6.72 | 0.001 |

| P-value | 0.442 b | 0.003 c | |

| Positive emotions | |||

| Control | 23.05 ± 6.30 | 24.40 ± 4.26 | 0.046 a |

| Intervention | 21.60 ± 4.58 | 31.30 ± 6.87 | 0.001 |

| P-value | 0.603 b | 0.001 c | |

| Negative emotions | |||

| Control | 29.75 ± 9.27 | 27.85 ± 6.75 | 0.144 a |

| Intervention | 34.15 ± 9.00 | 19.40 ± 5.87 | 0.001 |

| P-value | 0.627 b | 0.001 c | |

| Optimism | |||

| Control | 11.95 ± 4.75 | 12.35 ± 4.42 | 0.668 a |

| Intervention | 10.70 ± 4.85 | 16.85 ± 2.78 | 0.001 |

| P-value | 0.126 b | 0.001 c | |

a Paired samples t-test.

b Independent samples t-test.

c ANCOVA.

5. Discussion

The study found no significant differences in age, sex, or marital status between the experimental and control groups. However, there was a clear difference in their burn percentage grade, with more participants in the control group scoring between 36 - 45 percent compared to the intervention group.

The findings indicated a notable disparity between the intervention and control groups in life satisfaction scores. The present results are consistent with earlier research findings (17, 20). Lyubomirsky’s happiness training increased the life satisfaction scores in the intervention group compared to the control group. Additionally, the results indicated significant differences within groups in the stages before and after the intervention, with more pronounced changes observed in the intervention group. Therefore, the Lyubomirsky happiness training program had a significant effect on the life satisfaction of burn patients. It is concluded that the Lyubomirsky happiness training program significantly impacted life satisfaction.

The findings indicated a notable difference between the intervention and control groups regarding the average scores of both positive and negative emotions. The present results are consistent with earlier findings (18, 20). The results indicated that the Lyubomirsky happiness training program increased positive emotions and decreased negative emotions in the intervention group compared to the control group. Additionally, there were significant differences within groups in the stages before and after the intervention, with more pronounced changes observed in the intervention group. Therefore, the Lyubomirsky happiness training program significantly affected positive and negative emotions.

The outcomes of this study indicated a notable difference between the intervention and control groups in optimism, with increased scores in the intervention group compared to the control group. Also, the results indicated significant differences within groups in the stages before and after the intervention, with more pronounced changes observed in the intervention group. The findings align with previous results (17, 20). Therefore, the Lyubomirsky happiness training program significantly affected the optimism of burn patients, increasing their scores of optimism. The findings indicate that the happiness rate is determined by how individuals assess themselves and their lives. These assessments could involve a mental component, like judgments made about one's satisfaction with life, or an emotional component, which includes personality traits and feelings in response to life events.

5.1. Conclusions

This research indicates that the Lyubomirsky happiness training program aids burn victims in feeling joy and developing a positive outlook on life. Participants reported increased optimism, better relationships, and personal growth, leading to improved mental well-being. A positive mindset helps them handle challenges effectively. The training boosts joy and positive emotions, while negative thinking limits mental resources. Benefits include greater life meaning, energy, resilience, and success, with happiness being a key goal. The study found that a specific treatment improves happiness, optimism, and positive feelings in chronic burn patients while lowering negative emotions. Specialists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and clinicians are advised to use this method for better patient well-being. The study has limitations, such as including only patients from one hospital and using convenience sampling, which may limit broader application. Its main strength is its effectiveness in enhancing life satisfaction. Future researchers should explore this treatment for other chronic conditions with psychological aspects.