1. Background

Sleep is a vital biological requirement that critically influences immune system modulation, homeostatic regulation, and cognitive function enhancement. It further facilitates physiological process adaptation through hormonal regulation and anabolic activation (1). In intensive care unit (ICU) settings, environmental factors combined with critical illness severity result in significantly elevated rates of sleep disruption, encompassing both qualitative and quantitative deficits. Epidemiological data indicate that sleep disorder prevalence among critically ill patients varies between 22% and 61% (2, 3). This population demonstrates high rates of impaired sleep efficiency, fragmented sleep architecture, diminished restorative sleep stages, and recurrent nocturnal arousals (4). Assessing sleep in ICU patients presents significant methodological challenges. While objective measures, such as polysomnography (PSG) and actigraphy, represent the gold standard in assessments, their implementation is limited by the availability of specialized personnel and the need for specialized equipment in the ICU (5-7). Subjective questionnaire-based methods provide a practical alternative for assessing sleep quality and disruptive factors, offering advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness and feasibility. However, despite validation against objective measures for some instruments, many lack a comprehensive psychometric evaluation (6, 8-10). The Freedman Sleep Questionnaire (FSQ) is widely recognized as one of the most used tools for assessing sleep quality in ICU patients (11-15). Explicitly developed for ICU settings, the FSQ is a reliable and promising instrument for evaluating sleep in critically ill patients (13). Unlike other tools, the FSQ assesses both nighttime and daytime sleep quality in the ICU, thereby indicating patients’ sleep patterns before ICU admission. Unlike other instruments, such as the Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire, which focuses solely on general sleep quality (16), the FSQ also examines how ICU-specific factors, including noise, light, and frequent interventions, affect sleep. This unique focus on environmental and procedural disruptions allows healthcare providers to identify key determinants of sleep disturbances and design targeted interventions to improve patient sleep quality (16, 17). This study represents the first psychometric validation of the Arabic for Morocco version of the Freedman Sleep Questionnaire (AM-FSQ), making a significant contribution to the field of sleep assessment in ICU settings. The FSQ has been widely recognized as an effective tool for evaluating sleep quality in critically ill patients, particularly in English-speaking and other non-Arabic populations. However, to date, there has been no validated Arabic version of this instrument, which constitutes a notable gap in the literature. By validating the AM-FSQ, we enhance its applicability and reliability for Arabic-speaking populations, facilitating improved patient care and enabling more targeted interventions to manage sleep disturbances in critical care environments.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to validate the psychometric properties of the AM-FSQ and evaluate its suitability for assessing sleep quality in critically ill patients within Moroccan intensive care settings.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This psychometric study was conducted in the ICU of three hospitals in the Souss-Massa region, Morocco. It took place in the multi-purpose ICUs (26 beds) of the three hospitals. The study aimed to assess the reliability, stability, and conceptual and content validity of the tool.

3.2. Participants

The study included patients admitted to the ICU between May 15, 2024, and December 10, 2024. A convenience sample was used, following the recommendations of the Streiner guide, which were applied to estimate the sample size (18). The minimum number of subjects required is at least 140, considering an intra-class correlation coefficient of approximately 0.70 and a precision level of 0.10. The study included patients who met the following criteria: Critically ill patients admitted to the ICU who were over 18 years old, Arabic-speaking, and provided informed consent. Patients with hearing or speech impairments, pre-existing dementia diagnoses, documented substance use disorders, or Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores below 15 were excluded from the study.

3.3. Instrument

The subjective sleep quality of critically ill patients is evaluated using the FSQ, which considers environmental factors. The original questionnaire was developed by Freedman et al. (19) using a 10-point Likert scale to assess sleep quality. On this scale, 1 represents 'poor sleep quality' and 10 corresponds to 'excellent sleep quality'. A value of 1 denotes "inability to stay awake", while 10 represents "completely alert and awake". A value of 10 indicates a "significant interruption", while a value of 1 means "no interruption" in terms of environmental conditions.

3.4. Procedure

This study received ethical approval from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (CERB) of Rabat’s Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy (approval No. 85/24). All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional ethical standards and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (20). Authorization for data collection was obtained from the regional Department of Health and Social Protection in the Souss-Massa region. The original questionnaire developers and copyright holders authorized the cultural adaptation and linguistic validation of the FSQ in Arabic for Morocco. The tool used in this study was the FSQ, which subjectively assesses sleep quality in critically ill patients, considering environmental factors.

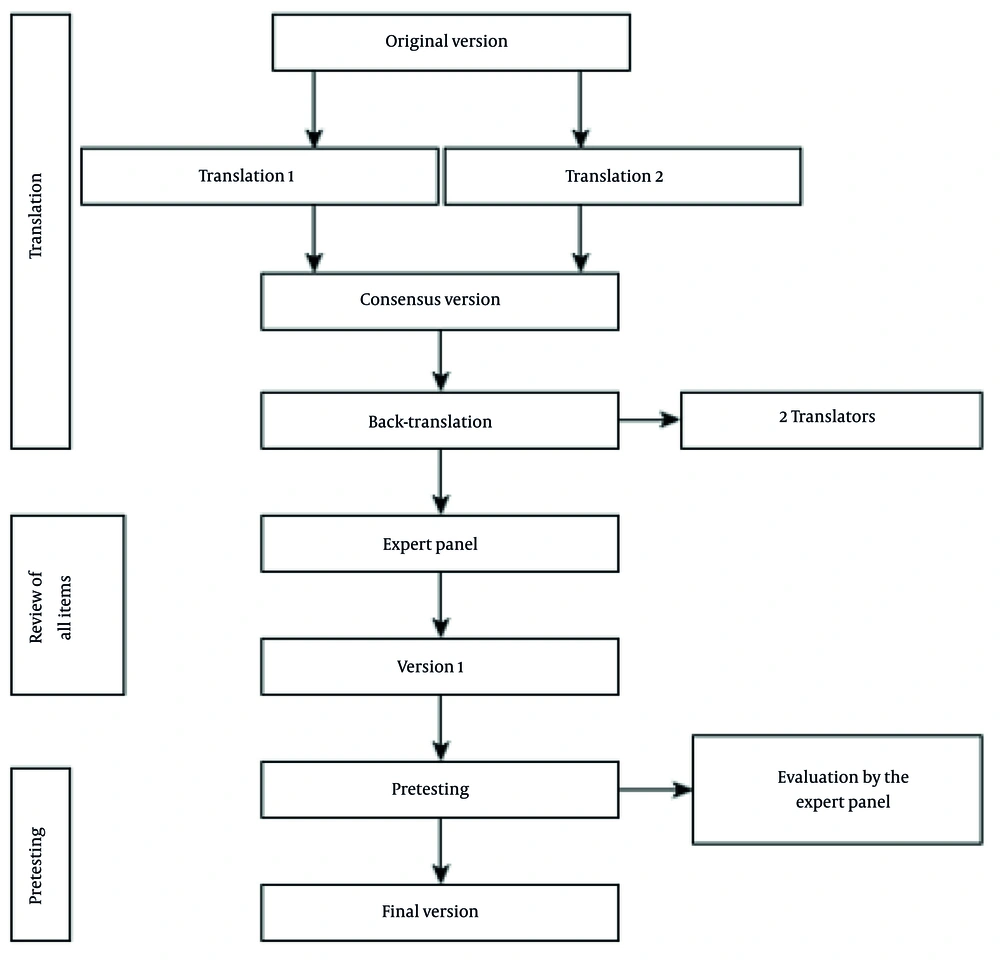

3.5. Translation and Cultural Adaptation of the Arabic for Morocco Version of the Freedman Sleep Questionnaire

The translation of the FSQ aimed to provide an Arabic for Morocco version of the questionnaire that maintained conceptual equivalence with the original English version. Dr. Nil Freedman, the original developer of the FSQ, was consulted, and permission was granted to translate the questionnaire. The AM-FSQ was developed according to established guidelines (20). Initially, two healthcare professionals specializing in intensive care, both fluent in English, independently translated the FSQ from English to Arabic for Morocco. These two versions were then compared and consolidated by an ICU expert with over 15 years of experience in critical care. A linguist and a sleep specialist, fluent in Arabic and English, subsequently performed a back-translation into English. A panel of eight bilingual healthcare professionals, all actively involved in the study, reviewed the six versions of the AM-FSQ. The translation process continued until all discrepancies were resolved, ensuring precision and accuracy. Finally, cognitive debriefing was conducted with four participants (four ICU physicians and one sleep specialist) to verify that each question of the AM-FSQ was clearly understood by all participants (Figure 1). The degree of convergence of the experts’ answers during the final validation was measured by the Aiken coefficient, which showed a very high level of agreement (V = 0.78). The validated version of the AM-FSQ was tested on 14 intensive care patients. Participants reported no ambiguity in their understanding of the questions. The final version of the AM-FSQ was not re-adjusted after testing. Data were collected at three time points: Upon ICU admission (baseline), at the midpoint of the ICU stay, and on the day of ICU discharge.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed for all study variables. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were presented as means ± standard deviations. Content validity was assessed through expert consensus, with the Content Validity Index (CVI) calculated using Davis’ method (21). Questionnaire reliability was evaluated through internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) and temporal stability [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in a test-retest approach] (22, 23). Construct validity was examined through an exploratory factor analysis with an Oblimin rotation (loading threshold ≥ 0.4), which identified four dimensions: Sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, environmentally induced sleep disturbances, and human factor-induced sleep disturbances. This analysis was preceded by adequacy tests: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure (acceptable ≥ 0.5; good ≥ 0.75) and Bartlett’s sphericity test (P < 0.05 required) (24). All analyses were conducted using JAMOVI software (version 2.3.28), with statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

Based on the inclusion criteria, 260 records of ICU patients were valid and included in the analysis. Their average age was 49.6 ± 18.42 years (range, 25 - 85); males constituted 46.6% of the sample. The mean length of ICU stay was 5.20 ± 2.47 days, with an observed range of 2 to 18 days. Regarding the cause of admission to the ICU, 72.2% were for medical conditions, 27.3% for postoperative care, 44.2% for acute heart disease, and 26.9% were related to respiratory diseases. Twenty percent of patients were smokers. Concerning clinical scores, the mean pain score was 3.79 ± 3.18, the Charlson comorbidities score was 1.02 ± 1.34, and the APACHE-II score was 9.60 ± 5.87 (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Total (n = 260) |

|---|---|

| Age | 49.65 ± 18.42 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 121 (46.5) |

| Female | 139 (53.5) |

| Admission reason | |

| Surgical | 71(27.3) |

| Medical | 189 (72.7) |

| Admission diagnosis | |

| Respiratory diseases | 70 (26.9) |

| Heart disease | 115 (44.2) |

| Metabolic disorders | 60 (23.1) |

| Other medical reasons | 15 (5.8) |

| Smokers | 52 (20) |

| APACHE-II score | 9.60 ± 5.87 |

| Charlson comorbidities score | 1.02 ± 1.34 |

| EVA-score | 3.79 ± 3.18 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | 5.20 ± 2.47 |

| Pregnancy | 33 (12.7) |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

4.2. Validity

Experts were consulted to determine the definition and relevance of each variable, thereby assessing the content validity of the questionnaire. The fact that most respondents answered 'more than 3' to the question indicates that this definition is accurate. Expert consensus was used to evaluate the content validity. Since "bed telephones" and "televisions" are not available in the ICU in Morocco, the assessments of these items were substituted with "personal telephone" and "conversation", respectively, by expert recommendations. Since these items were not present in intensive care units (ICUs), they were considered irrelevant. Following these modifications, the CVI of the Davis technique, which was previously determined to be 0.88, demonstrated a high level of content validity (25). The content validity analysis resulted in a final revised questionnaire, to which the responses were subsequently subjected during data collection. The KMO value was 0.845, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated adequate factorability of the data [χ² (351) = 8515, P < 0.001]. Our sample satisfies assumptions for factor analysis by varimax rotation (Table 2). The Oblimin rotation revealed a four-factor structure accounting for 70.8% of the total variance in the measured constructs (Table 2). Individual factor loadings ranged from 0.40 to 0.99 across all questionnaire items (Table 3).

| Factors | Oblimin Rotation/Factor Loadings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance (%) | Cumulative Variance (%) | |

| Disruptive noises | 6.32 | 23.4 | 23.4 |

| Disruptive activities | 5.38 | 19.9 | 43.3 |

| Quality of sleep | 3.80 | 14.1 | 57.4 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 3.63 | 13.4 | 70.8 |

a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin = 0.845; Bartlett’s test of sphericity: χ2 = 8515, df = 351; P < 0.001.

| Freedman Questionnaire Items | Factors | Unicity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disruptive Noises | Disruptive Activities | Quality of Sleep | Daytime Sleepiness | ||

| Overall quality of sleep at home | - | - | 0.400 | - | 0.8062 |

| Overall quality of sleep in the ICU | - | - | 0.801 | - | 0.3455 |

| Overall quality of your sleep on the first day in the ICU | - | - | 0.940 | - | 0.1103 |

| Overall quality of your sleep in the ICU, mid-stay | - | - | 0.961 | - | 0.0758 |

| Overall quality of your sleep in the ICU, end of stay | - | - | 0.979 | - | 0.0532 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU stay | - | - | - | 0.851 | 0.2600 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during the ICU, on the first day | - | - | - | 0.875 | 0.2357 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU, mid-stay | - | - | - | 0.986 | 0.0304 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU, end of stay | - | - | - | 0.938 | 0.1147 |

| Disruptive activities-noise | - | 0.511 | - | - | 0.6504 |

| Disruptive activities-light | - | 0.983 | - | - | 0.0364 |

| Disruptive activities-nursing interventions | - | 0.453 | - | - | 0.7160 |

| Disruptive activities-diagnostic testing | - | 0.983 | - | - | 0.0271 |

| Disruptive activities-vital signs measurement | - | 0.991 | - | - | 0.0215 |

| Disruptive activities-blood samples | - | 0.977 | - | - | 0.0463 |

| Disruptive activities-administration of medicines | - | 0.900 | - | - | 0.1748 |

| Disruptive noises-heart-monitor alarm | 0.992 | - | - | - | 0.0133 |

| Disruptive noises-ventilator alarm | 0.944 | - | - | - | 0.0885 |

| Disruptive noises-ventilator sound | 0.992 | - | - | - | 0.0133 |

| Disruptive noises-oxygen finger probe | 0.966 | - | - | - | 0.0813 |

| Disruptive noises-talking | 0.925 | - | - | - | 0.1402 |

| Disruptive noises-IV-pump | 0.933 | - | - | - | 0.1193 |

| Disruptive noises- suctioning | 0.992 | - | - | - | 0.0133 |

| Disruptive noises- nebulizer | 0.992 | - | - | - | 0.0133 |

| Disruptive noises-doctors’ beeper | 0.992 | - | - | - | 0.0133 |

| Disruptive noises- conversations | 0.751 | - | - | - | 0.4516 |

| Disruptive noises– personal telephone | 0.754 | - | - | - | 0.4369 |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

4.3. Reliability

4.3.1. The Test-Retest Method

The consistency of the AM-FSQ was evaluated through inter-observer comparison. Test-retest analysis using ICC demonstrated excellent reliability across all assessed items, with an ICC range of 0.715 to 0.997, as detailed in Table 4.

| Freedman Items | Test a | Retest a | Test b | Retest c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall quality of sleep at home | 7.25 ± 3.00 | 7.63 ± 2.16 | 0.808 | 0.542 - 0.928 |

| Overall quality of sleep in the ICU | 5.56 ± 3.05 | 5.69 ± 2.47 | 0.739 | 0.409 - 0.899 |

| Overall quality of your sleep on the first day in the ICU | 5.31 ± 2.77 | 5.25 ± 2.46 | 0.932 | 0.821 - 0.975 |

| Overall quality of your sleep in the ICU, mid-stay | 5.44 ± 3.03 | 5.81 ± 2.43 | 0.892 | 0.727 - 0.961 |

| Overall quality of your sleep in the ICU, end of stay | 5.56 ± 3.05 | 5.63 ± 2.96 | 0.997 | 0.990 - 0.999 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU stay | 6.75 ± 2.74 | 7.06 ± 1.95 | 0.873 | 0.682 - 0.953 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during the ICU, on the first day | 6.06 ± 2.82 | 6.25 ± 2.79 | 0.956 | 0.833 - 0.984 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU, mid-stay | 6.44 ± 2.73 | 6.56 ± 2.34 | 0.913 | 0.774 - 0.968 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU, end of stay | 6.75 ± 2.74 | 6.75 ± 2.84 | 0.984 | 0.956 - 0.994 |

| Disruptive activities-noise | 6.25 ± 2.84 | 6.25 ± 2.49 | 0.912 | 0.773 - 0.968 |

| Disruptive activities-light | 7.38 ± 2.39 | 7.25 ± 2.21 | 0.858 | 0.648 - 0.947 |

| Disruptive activities-nursing interventions | 5.19 ± 2.14 | 5.38 ± 2.36 | 0.982 | 0.949 - 0.993 |

| Disruptive activities-diagnostic testing | 4.38 ± 1.31 | 4.19 ± 1.17 | 0.858 | 0.649 - 0.948 |

| Disruptive activities-vital signs measurement | 6.25 ± 2.7 | 6.50 ± 2.48 | 0.953 | 0.875 - 0.983 |

| Disruptive activities-blood samples | 6.13 ± 2.22 | 6.56 ± 2.58 | 0.930 | 0.817 - 0.975 |

| Disruptive activities-administration of medicines | 5.19 ± 2.14 | 5.69 ± 2.41 | 0.917 | 0.784 - 0.970 |

| Disruptive noises-heart-monitor alarm | 7.44 ± 2.45 | 7.44 ± 2.34 | 0.934 | 0.827 - 0.976 |

| Disruptive noises-ventilator alarm | 4.19 ± 3.62 | 4.50 ± 3.58 | 0.969 | 0.915 - 0.989 |

| Disruptive noises-ventilator sound | 4.19 ± 3.62 | 4.50 ± 3.56 | 0.973 | 0.927 - 0.991 |

| Disruptive noises-oxygen finger probe | 6.25 ± 2.70 | 6.25 ± 2.52 | 0.954 | 0.877 - 0.984 |

| Disruptive noises-talking | 6.25 ± 2.84 | 6.56 ± 2.90 | 0.958 | 0.888 - 0.985 |

| Disruptive noises -IV-pump | 4.06 ± 3.62 | 4.31 ± 3.72 | 0.991 | 0.974 - 0.997 |

| Disruptive noises-suctioning | 3.94 ± 3.26 | 4.25 ± 3.32 | 0.986 | 0.960 - 0.995 |

| Disruptive noises-nebulizer | 5.00 ± 3.46 | 5.00 ± 3.20 | 0.966 | 0.909 - 0.988 |

| Disruptive noises-doctors’ beeper | 1.50 ± 0.64 | 1.50 ± 0.730 | 0.730 | 0.393 - 0.896 |

| Disruptive noises-conversations | 1.50 ± 0.64 | 1.63 ± 0.50 | 0.715 | 0.202 - 0.845 |

| Disruptive noises-personal telephone | 1.75 ± 1.00 | 1.56 ± 0.727 | 0.878 | 0.694 - 0.955 |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

a Values are presented as mean ± SD.

b ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

c 95% CI.

4.3.2. Internal Consistency and Item Analysis

The AM-FSQ demonstrated good reliability with an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.816. Item-total correlations ranged from 0.04 to 0.59 (Table 5), with most items showing acceptable correlation values (> 0.30).

| Freedman Questionnaire Items | Mean ± SD | Item-Remainder Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall quality of sleep at home | 7.06 ± 1.918 | 0.1199 | 0.816 |

| Overall quality of sleep in the ICU | 4.13 ± 2.133 | 0.0413 | 0.821 |

| Overall quality of your sleep on the first day in the ICU | 4.43 ± 2.030 | 0.0724 | 0.819 |

| Overall quality of your sleep in the ICU, mid-stay | 4.61 ± 2.063 | 0.0682 | 0.819 |

| Overall quality of your sleep in the ICU, end of stay | 4.78 ± 2.143 | 0.0833 | 0.819 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU stay | 6.05 ± 2.031 | 0.1162 | 0.817 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during the ICU, on the first day | 5.52 ± 2.153 | 0.2639 | 0.810 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU, mMid-stay | 5.77 ± 1.979 | 0.1891 | 0.813 |

| Overall degree of daytime sleepiness during ICU, end of stay | 6.04 ± 2.031 | 0.1539 | 0.815 |

| Disruptive activities-noise | 6.75 ± 2.293 | 0.3095 | 0.808 |

| Disruptive activities-light | 6.88 ± 2.117 | 0.5755 | 0.795 |

| Disruptive activities-nursing interventions | 4.88 ± 2.083 | 0.2889 | 0.809 |

| Disruptive activities-diagnostic testing | 6.85 ± 2.013 | 0.5769 | 0.795 |

| Disruptive activities-vital signs measurement | 6.87 ± 2.080 | 0.5745 | 0.795 |

| Disruptive activities-blood samples | 6.78 ± 2.000 | 0.5514 | 0.796 |

| Disruptive activities-administration of medicines | 6.68 ± 2.043 | 0.5423 | 0.797 |

| Disruptive noises-heart-monitor alarm | 2.50 ± 1.578 | 0.5433 | 0.799 |

| Disruptive noises-ventilator alarm | 2.49 ± 1.633 | 0.5802 | 0.797 |

| Disruptive noises-ventilator sound | 2.13 ± 1.060 | 0.5122 | 0.803 |

| Disruptive noises-oxygen finger probe | 2.34 ± 1.283 | 0.5415 | 0.801 |

| Disruptive noises-talking | 2.56 ± 1.764 | 0.5965 | 0.796 |

| Disruptive noises-IV-pump | 2.19 ± 1.372 | 0.4289 | 0.804 |

| Disruptive noises-suctioning | 2.35 ± 1.411 | 0.4809 | 0.802 |

| Disruptive noises-nebulizer | 2.25 ± 1.407 | 0.5164 | 0.801 |

| Disruptive noises-doctors’ beeper | 1.55 ± 0.821 | 0.2614 | 0.810 |

| Disruptive noises-conversations | 1.62 ± 0.784 | 0.3100 | 0.809 |

| Disruptive noises-personal telephone | 1.89 ± 1.367 | 0.4361 | 0.804 |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

5. Discussion

Global critical care societies have issued evidence-based recommendations to enhance safety standards and improve clinical outcomes for critically ill patients in the ICU. Growing clinical and research attention has focused on sleep quality assessment as mounting evidence demonstrates its profound impact on post-ICU recovery. Sleep disturbances in the ICU are significantly associated with multiple adverse outcomes, including neuropsychological complications (elevated delirium risk, cognitive dysfunction, and mood disorders) and physiological impairments (immune suppression, metabolic dysregulation, and prolonged fatigue) (26-28). These findings have led to strong consensus recommendations (grade 1B) for implementing routine sleep monitoring and targeted intervention protocols in critical care settings (29).

Various methods, including questionnaires, have been employed to assess the sleep quality of ICU patients. Compared to PSG, questionnaires offer the advantage of facilitating the implementation of effective sleep-quality improvement interventions and evaluating a larger patient cohort, both in the short and long term (6, 7, 10, 29). The FSQ, which is the focus of the current validation study, provides a subjective assessment of sleep quality in ICU patients while specifically evaluating environmental disruptors. This instrument offers practical clinical utility due to its ease of administration in critical care populations. Existing research utilizing the FSQ has consistently identified routine care activities, particularly vital sign monitoring, and nursing interventions, as the most significant disruptive factors affecting patient sleep (12, 13, 15).

The results from our study indicate that the AM-FSQ demonstrates acceptable psychometric properties and is suitable for evaluating ICU patients’ sleep quality in Morocco (CVI = 0.88 > 0.80; KMO Index = 0.845, indicating good suitability of data for factor analysis; The psychometric analysis revealed that all factor loadings (0.40 - 0.99) exceeded the 0.30 criterion, confirming good item-factor relationships and the test-retest reliability showed excellent consistency (ICC = 0.86 > 0.70 threshold); Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81 > 0.70). We acknowledge that some items showed variability in test-retest reliability, reflected in the wide ICC ranges (0.542 to 0.928). This variability may result from differences in patient conditions, the ICU environment, or fluctuations in sleep patterns. Nevertheless, the overall test-retest reliability of the AM-FSQ remains strong, indicating its general stability.

However, one limitation identified by the researchers was the lack of comprehensive validation and reliability testing during the initial development of the questionnaire by Freedman et al. (19) The original FSQ has several psychometric limitations, including cultural biases and limited applicability to diverse ICU populations. It also may not fully capture ICU-specific sleep disturbances, such as noise and frequent medical interventions. In this study, we addressed these limitations by adapting the AM-FSQ for Arabic-speaking populations and conducting rigorous psychometric validation to enhance its cultural and contextual relevance for ICU settings.

The psychometric properties of the FSQ were evaluated in only two prior studies, one in Spanish and one in Turkish (11, 14), where expert evaluations confirmed that the questionnaire’s items were accurate and valuable. Their study also reported an adequate sample size, as reflected by the KMO value of 0.845. In line with our research, the original and Spanish versions of the questionnaire exhibited a four-factor structure comprising sleep interruption, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, and environmental sleep interruption (11). Conversely, the Turkish validation study established a three-factor model comprising perceived sleep quality, daytime somnolence manifestations, and environmentally mediated sleep disruptions (14). The differences between our 4-factor model and the 3-factor model of the Turkish version may stem from cultural, procedural, or methodological factors. Variations in patient characteristics, healthcare settings, and environmental factors may contribute to these discrepancies. Additionally, differences in data analysis techniques or sample composition could have contributed to the divergent results. Similar findings were observed in studies of the Spanish and Turkish versions of the questionnaire, which reported high Cronbach’s alpha values (> 0.8) and ICC values greater than 0.75 for each item.

Given our promising study results, the AM-FSQ holds significant clinical potential. It can serve as a standard assessment tool in ICU settings to identify good and poor sleepers and guide healthcare professionals in formulating appropriate treatment strategies. The patients in our study were more conscious and responsive, which may make them more sensitive to sleep disruptions and noise compared to sedated, comatose, or unresponsive patients.

5.1. Conclusions

The Moroccan version of the Freedman questionnaire shows excellent reliability and validity for assessing ICU sleep quality in Morocco. Its simple administration makes it practical for routine clinical use by ICU teams to identify sleep disturbances early and determine the factors affecting patients’ sleep. We suggest that the AM-FSQ be applied in multicenter and longitudinal studies to evaluate its responsiveness to interventions, thereby providing further insights into its utility in assessing sleep quality improvements across different clinical contexts. Implementing targeted interventions to promote healthy sleep and improve overall sleep quality in ICU patients may be beneficial. Additionally, it can be utilized in clinical research to assess sleep quality in correlation with other variables, such as depression, anxiety, and quality of life, in ICU settings.

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

The researchers implemented several strategies to minimize bias throughout this study. The translation process rigorously followed established protocols and underwent multiple rounds of expert review, significantly strengthening the validity of the translated version. A single investigator carried out data collection, which helped mitigate the risk of performance bias. Additionally, the diverse range of diagnoses within the sample improved the generalizability of the results and reduced the potential for selection bias. Despite the study’s findings, it is essential to recognize that questionnaire-based assessments are inherently subjective and can only serve as a substitute for objective evaluation methods when the latter are not feasible.

The study adopted a convenience sampling approach, wherein patients were selected based on their availability and willingness to participate. While this method is efficient, it may introduce potential selection bias. To minimize this bias, the sample was diverse in terms of age, pathologies, and severity of illness. A comparison between the characteristics of participants and non-participants revealed no significant differences. Moreover, the participation rate exceeded 94% of the target population, which further mitigates the risk of selection bias.

The exclusion of patients with a GCS score of less than 15 was a deliberate decision made to enhance the validity of the collected data. By excluding these patients, we aimed to ensure that the participants included in the study could provide clear and valid responses, thereby ensuring the reliability of the psychometric evaluation of the Arabic version of the AM-FSQ. While this exclusion limits the generalizability of the findings to more critically ill patients, it was necessary to maintain the internal validity of the study. Future research should focus on recruiting a larger and more diverse sample from multiple centers to explore further the correlations between patient demographics, clinical characteristics, perceptions of sleep quality, and the underlying factors contributing to poor sleep in critically ill patients.