1. Context

Infectious diseases are the second leading cause of death worldwide (1). Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is one of the important and problematical infectious pathogens (2). It is an opportunistic pathogen and is the primary cause of lower respiratory tract and surgical site infections, and the second leading cause of nosocomial bacteremia, pneumonia, and cardiovascular infections (3). Moreover, S. aureus is often found among chronic and recurrent bone infections, and is often the cause of chronic osteomyelitis, endocarditis, infections of indwelling devices and postsurgical wound infections such as chronic biofilm-associated infections in prosthetic devices (4). In recent years, the emergence of antibiotic-resistant forms of pathogenic S. aureus is a worldwide problem in clinical medicine (5). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is the most common antibiotic-resistant of all antibiotic-resistant threats. The MRSA was first identified five decades ago (6). Hereafter, MRSA infections have spread in Europe, the Americas, and the Asia-Pacific region (7). Hence the search for newer, safer and more potent antimicrobials with less susceptibility to the resistance is a pressing need (8). Evidence currently shows that improved quality of life is considerably important in the treatment of chronic diseases (9). The negative effects of chronic infection induced by MRSA on the quality of life increase the need to search for newer, safer, and more potent antimicrobial agents with less susceptibility to resistance is a pressing need (8).

Plants were commonly used in the treatment of diseases by a primary human from ancient times. (9). Over the years, the World Health Organization (WHO) advocated traditional medicine as safe remedies for both microbial and non-microbial diseases. According to the WHO in 2008, above 80% of the world’s population rely on traditional medicine for their primary healthcare needs (10). On the other hand, almost one-third of all medical products have a plant origin (11). Plants contain a variety of compounds against a variety of pathogens. It means that plants have wide-spreading effects against a different variety of infectious agents, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Thus recently, the research is growing on medical plants as safe, cheap, accessible, and more acceptable for peoples than synthetic antibiotics (12).

The diversity of the climate has resulted in a high diversity of plant flora in Iran. So it is possible to identify effective substances in different native plants of the country and to extract these substances in order to produce these materials in large quantities at the industrial level. Evaluation of these capabilities, especially in the case of plants native to Iran is of special importance (13). A considerable number of articles are published annually on the antimicrobial effect of various Iranian plants. Given the growing problem of antibiotic resistance, analyzing and summarizing the results of these articles will be important for their practical use. Moreover, the comparison between pharmaceutical effects of different parts of a medical plant can give a good vision for accomplishing further study with more efficiency.

2. Objectives

The aim of the present systematic review was to deliberate on whether plants, found commonly in Iran, could be used as an alternative for infection therapy. This review would describe some of the Iranian plant species as potent therapeutic agents specifically against S. aureus and its frequent resistant strain, MRSA. It also compared the antimicrobial potential of different Iranian herbs to highlight the most functional of them.

3. Data Sources

The present systematic review study was conducted after obtaining prior permission from the Research Ethics Committee (code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1396.150). This review involves searching for available literature about plants and herbal compounds effective against S. aureus and MRSA. To find related articles, we searched several databases, including PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Springer Link, Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar databases and Persian databases, including Iran Medex (indexing articles published in Iran biomedical journals), Magiran (Iranian magazines database), and SID (scientific information database) using a list of keywords in MeSH such as medical plant, healing plants, pharmaceutical plants, medical herbs, healing plants, plant extracts, plant drug, Iranian medical plants, antimicrobial susceptibility, Staphylococcus aureus, plant antimicrobial extract, microbial sensitivity tests, plant biologically active compounds, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, as well as a combination of them. We studied all related articles, collected, and classified all relevant data published from January 1, 1974 to January 2017.

4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

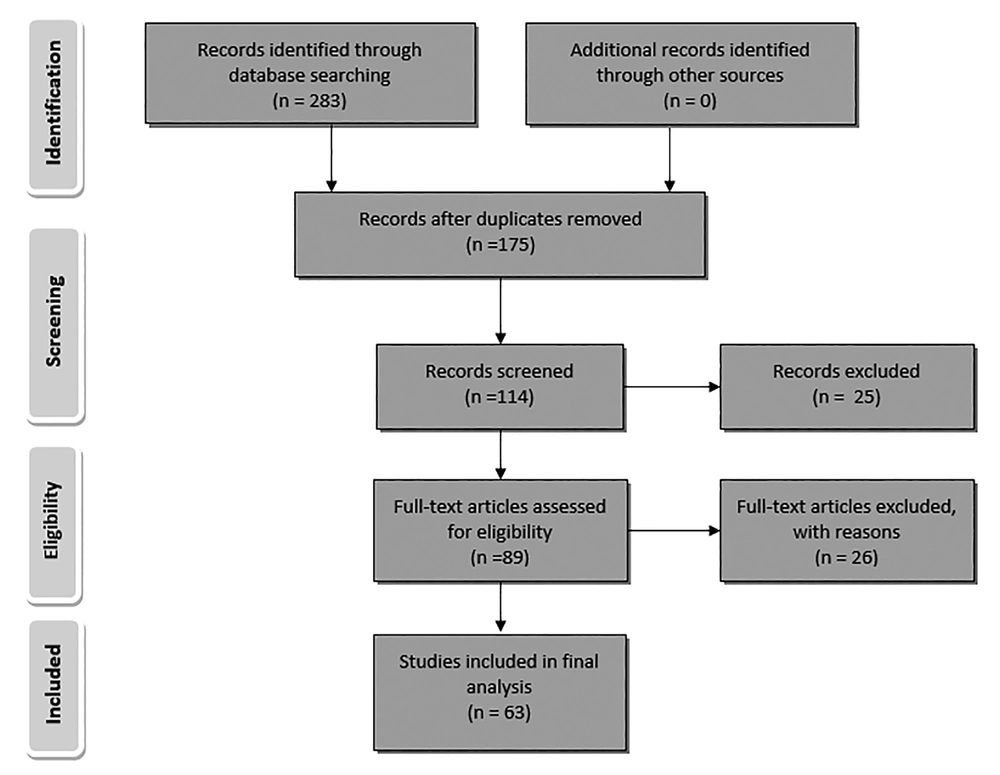

All research articles that focused on the antimicrobial assay of essential oil or at least one of the different extracts (methanolic, ethanolic, ethyl acetate, ether or aqueous) from plants, growing in Iran, by Microdilution method and Kirby-Bauer test (zone of inhibition test) against S. aureus, published from January 1, 1974 to January 2017 were included in this study. All other relevant research articles that used other antimicrobial assays did not investigate the antimicrobial effect against S. aureus or were out of desired time range were excluded from the study. A flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of this review (Figure 1).

5. Results

This systematic review compared the result of research articles that determined the antimicrobial activity of essential oil and different extracts (methanolic, ethanolic, ethyl acetate, ether or aqueous extracts) from different parts of 31 genera of medical plants, including 83 species, especially against S. aureus. All described herbal medicine with the details of using part of the plant, types of extracts, maximum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and inhibition zone against S. aureus, location of harvesting, and the references are summarized in Table 1. The map of Iran along with the provinces is shown in Figure 2 so that the harvesting areas of the plants can be traced back to the map.

| Plant | References | Using Part | Extraction | Inhibition Zone (IZ) | MIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dicyclophora persica | (19) | Aerial part | Essential oil | 20 mm | 1.2 mg/mL |

| Nepeta cripsa | (20) | Aerial part | Essential oil | 19.5 mm (15 μL/disc) | |

| Nepeta menthoid | (21) | Aerial part | Essential oil | 21 mm (10 μL/disc) | 3.6 mg/mL |

| Terminalia chebula | (22) | Ripe and unripe seed | Methanolic extract | 5 mg/mL for ripe seed 2.5 mg/mL for unripe seed | |

| Myrtus communis | (23) | Leaves and seeds | Methanolic extract | 26 mm (20 mg/mL), 10 mm (5 mg/mL) for leaves 16 mm(20 mg/mL), 9 mm (0.62 mg/mL) for seeds | 5 mg/mL (leaves) 0.62 mg/mL (for seed) |

| Salvia multicaulis | (24) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 7.5 mg/mL | |

| Salvia multicaulis | (25) | Methanolic extract | 10 mm (S. aureus penicillin-resistant) | ||

| Salvia sclarea | (24) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 15 mg/mL | |

| Salvia verticillata | (24) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 7.5 mg/mL | |

| Salvia limbata | (26) | Essential oil | 15 mg/mL | ||

| Salvia choloroleuca | (26) | Essential oil | 7.5 mg/mL | ||

| Salvia officinalis | (22) | Whole plant | Methanolic extract | 16 mm | |

| Salvia sahendica | (27) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 14 mm | 1.2 mg/mL |

| Salvia reuterana | (28) | Flower and leaves | Methanolic extract | 0.5 mg/mL for flower, 0.25 mg/mL for leaves | |

| Salvia eremophila | (29) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract and essential oil | 7.8 mg/mL for essential oil, 0.5 mg/mL for methanolic extract | |

| Salvia eremophila | (30) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 10 mm (4 mg/disc) | 1 mg/mL |

| Salvia reuterana | (30) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 8 mm (4 mg/disc) | 1 mg/mL |

| Salvia mirzayanii | (30) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 12.2 mm (4 mg/disc) | 1 mg/mL |

| Salvia santolinifolia | (30) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 12.2mm (4 mg/disc) | 1 mg/mL |

| Salvia microsiphon | (30) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 14.2 mm (4 mg/disc) | 1 mg/mL |

| Salvia urmiensis | (31) | Ethyl acetate extract | 21.3 μg/mL | ||

| Salvia urmiensis | (31) | Essential oil | 85.3 μg/mL | ||

| Salvia urmiensis | (31) | Ether extracts | 37.3 μg/mL | ||

| Salvia tomentosa | (32) | Mature plant | Aqueous extract | NA for MRSAa & S. aureus strains | |

| Salvia tomentosa | (32) | Mature plant | Ethanolic extract | 8.4 mm (4 mg/disc for MRSAa) 6.8 mm(4 mg/disc for S.aureus) | |

| Alhagi maurorum | (22) | Stem gum | Methanolic extract | 15 mm | |

| Heracleum rechingeri | (22) | Fruit | Methanolic extract | 20 mm | |

| Heracleum transcaucasicum | (33) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | NA | |

| Heracleum anisactis | (33) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | NA | |

| Foeniculum vulgare | (34) | Fennel seeds | Essential oil | 2% | |

| Foeniculum vulgare | (22) | Fennel root | Methanolic extract | 12 mm | |

| Cuminum cyminum | (35) | Essential oil | 10 mm (10 μL/disc) | 1/8 oil dilution | |

| Cuminum cyminum | (22) | Fruit | Methanolic extract | 12 mm | |

| Cuminum cyminum | (23) | Seeds | Methanolic extract | 15 mm | |

| Cuminum cyminum | (32) | Seeds | Aqueous extract | NA for MRSAa and S. aureus | |

| Cuminum cyminum | (32) | Seeds | Ethanolic extract | 11.5 mm (4 mg/disc for MRSAa) 8.5 mm(4 mg/disc for S. aureus) | |

| Artemisia diffusa | (36) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 18.4 mm (16 mg/cup) | 10 mg/mL |

| Artemisia oliveria | (36) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 12.2 mm (16 mg/cup) | 10 mg/mL |

| Artemisia scorpia | (36) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 13.6 mm (16 mg/cup) | 10 mg/mL |

| Artemisia turanica | (36) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 11.9 mm (16 mg/cup) | 10 mg/mL |

| Artemisia dracunulus | (34) | Essential oil | 7.0% | ||

| Artemisia dracunulus | (32) | Mature plant | Ethanolic extract | 8 mm(4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 7 mm(4 mg/disc for S. aureus) | |

| Artemisia dracunulus | (32) | Mature plant | Aqueous extract | NA (for MRSAa & S. aureus) | |

| Artemisia herbalba | (32) | Mature plant | Ethanolic extract | 22.5 mm(4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 11 mm (4 mg/disc for S. aureus) | 0.39 mg/mL (for clinical MRSAa and S. aureus strains) 0.04 mg/mL (for standard MRSAa strain) 0.02 mg/mL(for standard S. aureus strain) |

| Artemisia herbalba | (32) | Mature plant | Aqueous extract | 12 mm(4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 9 mm(4 mg/disc for S. aureus) | |

| Artemisia absinthium | (32) | Mature plant | Ethanolic extract | 9 mm(4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 8 mm(4 mg/disc for S. aureus) | |

| Artemisia absinthium | (32) | Mature plant | Aqueous extract | NA (for MRSAa & S. aureus) | |

| Pistacia vera | (37) | Fruit | Extract | 32 mm | |

| Pistacia mutica | (37) | Fruit | Extract | 18 mm | |

| Pistacia vera | (37) | Leaves | Extract | 22 mm | |

| Pistacia mutica | (37) | Leaves | Extract | 22 mm | |

| P. khinjuk | (38) | Leaves | Chloroform | 0.04 mg/mL | |

| P. khinjuk | (38) | Leaves | Ethyl acetate | 0.13 mg/mL | |

| P. khinjuk | (38) | Leaves | Ethyl alcohol | 0.09 mg/mL | |

| P. khinjuk | (38) | Leaves | Diethyl ether | 0.42 mg/mL | |

| P. atlantica | (39) | Mastic gum | Essential oil | 11 mm (10 μL/disc ) 13 mm (20 μL/disc) | |

| Helichrysum armenium | (40) | Flower, leaf and stem | Oil | 12.4 mm, 11.22 mm and 10.8 mm (50 μL/cup) | |

| Helichrysum scabrum | (41) | Flower | Extract | 9mm to 19mm | MIC value varied from lower than 19 μg/mL to 5000 μg/mL |

| Scrophulari astriata | (42) | Leaves | Ethanolic extract | 50.6 μg/mL | |

| Thymus persicus | (43) | Leaves | Essential oil | 0.5 μL/mL | |

| Thymus eriocalyx | (43) | Leaves | Essential oil | 0.5 μL/mL | |

| Thymus pubescens | (44) | Pre and flowering stages | Essential oil | 29 mm for pre and 34 mm for flowering | dilution of 1/8 |

| Thymus serpyllum | (44) | Pre and flowering stages | Essential oil | 14 mm for pre and 22 mm for flowering | dilution of 1/4 |

| Thymus pubescens | (45) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 8 to 16 mm | |

| Thymus vulgaris | (34) | Leaves | Essential oil | 0.1% | |

| Thymus vulgaris | (22) | Whole plant | Methanolic extract | 10 mm | 5 mg/mL |

| Thymus vulgaris | (46) | Essential oil | 20 - 35 mm (for 14 clinical MRSAa strains) 19 mm (for S. aureus) | 18.5 µg/ml -37 µg/mL (for 14 clinical MRSAa strains) 18.5 µg/mL (for S. aureus) | |

| Thymus vulgaris | (32) | Mature plant | Ethanolic extract | 10.5 mm (4 mg/disc for MRSAa) 9.4 mg/disc for S. aureus | |

| Thymus vulgaris | (32) | Mature plant | Aqueous extract | NA (for MRSAa & S. aureus) | |

| Thymus caramanicus | (32) | Mature plant | Ethanolic extract | 11.2 mm (4 mg/disc for MRSAa) 9 (4 mg/disc for S. aureus | |

| Thymus caramanicus | (32) | Mature plant | Aqueous extract | NA (for MRSAa & S. aureus) | |

| Thymus caucasicus | (47) | Essential oil | 0.31 μg/mL for S. aureus 2.5 μg/mL for MRSAa | ||

| Mentha pulegium | (48) | Flowering aerial parts | Essential oil | 21 mm (1 μL of oil) | 0.5 μL/mL |

| Mentha pulegium | (34) | Leaves | Essential oil | 0.5% | |

| Menth apiperita | (49) | Essential oil | 2 μL/mL | ||

| Mentha piperita | (34) | Leaves | Essential oil | 0.4% | |

| Mentha piperita | (32) | Leaves | Ethanolic extract | 7.5 mm (4 mg/disc for MRSAa) 8.5 (4 mg/disc for S. aureus | |

| Mentha piperita | (32) | Leaves | Aqueous extract | 7 mm (4 mg/disc for MRSAa) 7.5 mm (4 mg/disc for S. aureus) | |

| Peganum harmala | (50) | Seed smoke | Dichloromethane extract | 15.7 mm(5 mg of smoke condensate) | |

| Peganum harmala | (32) | Mature plant | Aqueous extract | 7.4 mm(4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) NA (4 mg/disc) | |

| Peganum harmala | (32) | Mature plant | Ethanolic extract | 18 mm(4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 20 mm(4 mg/disc) | 0.02 mg/mL (for clinical and standard MRSAa strains) 0.02 mg/mL(for standard and clinical S. aureus strains) |

| Peganum harmala | (51) | Seed | Methanolic extract | 22 mm (in concentration of 400 mg/mL for MRSAa) | 0.625 mg/mL |

| Peganum harmala | (51) | Leaves | Methanolic extract | 10 mm (in concentration of 400 mg/mL for MRSAa) | |

| Peganum harmala | (51) | Stem | Methanolic extract | 11 mm (in concentration of 400 mg/mL for MRSAa) | |

| Peganum harmala | (51) | Root | Methanolic extract | 24.5 mm (in concentration of 400 mg/mL for MRSAa) | 0.625 mg/mL |

| Peganum harmala | (51) | Flower | Methanolic extract | 5.5 mm (in concentration of 400 mg/mL for MRSAa) | |

| Grammosciadium platycarpum | (52) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 18 mm | 1.9 mg/mL |

| Grammosciadium scabridum | (53) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 14 mm (10 μg/disc) | 1.2 mg/mL |

| Onosmadi chroanthum | (54) | Root | Methanolic and ethanolic extract | 15 mm (50 μL/well), 15 mm (50 μL/well) | 0.156 mg/mL for methanolic extract and 0.312 mg/mL for ethanolic extract |

| Scutellaria litwinowii | (55) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 6.25 mg/mL | |

| Scutellaria lindbergii | (55) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 6.25 mg/mL | |

| Oliveria decumbens | (56) | Aerial parts | Ethanolic and methanolic exracts | 20 mg/mL, 20 mg/mL | |

| Teucrium polium | (57) | Aerial parts | Alcoholic extracts | 40 mg/mL | |

| Teucrium polium | (58) | Hydroalcholic | 20 mm | ||

| Stachys fruticulosa | (27) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 12 mm | 2.5 mg/mL |

| Stachys schtschegleevii | (27) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 13 mm | 1.25 mg/mL |

| Stachys byzantia | (59) | Methanolic extract | 8.4 mm | 100 μg/mL | |

| Stachys inflate | (59) | Methanolic extract | 8.3 mm | 250 μg/mL | |

| Stachys lavandulifolia | (59) | Methanolic extract | 8.6 mm | 500 μg/mL | |

| Stachys laxa | (59) | Methanolic extract | 8.6 mm | 100 μg/mL | |

| Stachys grandiflora | (60) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 12 mm | |

| Stachys obtusicrena | (30) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 9.2 mm (4 mg/disc) | |

| Hymenocrater longiflorus | (61) | Polar sub-fraction | Essential oil | 31 mm | 40 μg/mL |

| Pistachia vera | (62) | Green hull | Purified extract | 11.7 mm (at 1200 μg/plate) | |

| Phlomis caucasica | (27) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 1.25 mg/mL | |

| Phlomis buruguieri | (59) | Aerial parts | Mehanolic extract | 16.7 mm | 10 mg/mL |

| Phlomis herbaventi | (59) | Aerial parts | Mehanolic extract | 12.2 mm | 10 mg/mL |

| Phlomis oliveri | (59) | Aerial parts | Mehanolic extract | 13.1 mm | 25 mg/mL |

| Torilis leptophyla | (63) | Aerial parts | Ethanolic extract | 10 mm | 0.4 g/mL |

| Tanacetum balsamita | (27) | Aerial parts | Dichloromethane extract | 2.5 mg/mL | |

| Tanacetum parthenium | (11) | Whole plant | Essential oil | 18.5 mm (2.5 μL), 34mm (5 μL), 39mm (7.5 μL) and 42 mm (15 μL) | 1 μg/mL |

| Tanacetum parthenium | (64) | Flowering stage | Essential oil | 24 mm | 8 μg/mL |

| Tanacetum parthenium | (64) | Pre-flowering stage | Essential oil | 18 mm | 8 μg/mL |

| Tanacetum parthenium | (64) | Post-flowering stage | Essential oil | 22 mm | 8 μg/mL |

| T. pinnatumboiss | (65) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 24.2 mm | |

| Achillea millefollum | (27) | Methanolic extract | 0.625 mg/mL | ||

| Achillea millefollum | (66) | Essential oil | 31.4 mm (region 1) 19.8 mm(region 2) | 15.4 μg/mL (region 1) 27.5 μg/mL (region 2) | |

| Achillea pachycephala | (67) | Flowers | Essential oil | 12 mm | |

| Achillea pachycephala | (67) | Leaves | Essential oil | 10.5 mm | |

| Achillea pachycephala | (67) | Stems | Essential oil | 8 mm | |

| Achillea pachycephala | (67) | Aerial parts | Hexan-ether | 14 mm | 6.25 mg/mL |

| Achillea pachycephala | (67) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 6 mm | 12.5 mg/mL |

| Achillea santolina | (67) | Flowers | Essential oil | 9 mm | |

| Achillea santolina | (67) | Leaves | Essential oil | 7.5 mm | |

| Achillea santolina | (67) | Stems | Essential oil | 6.5 mm | |

| Achillea santolina | (67) | Arial parts | Hexan-ether | 7 mm | 6.25 mg/mL |

| Achilleas antolina | (67) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 5 mm | 12.5 mg/mL |

| Achillea tenuifolia | (68) | Flower | Volatile oils | 14 mm | |

| Achillea tenuifolia | (68) | Leaves | Volatile oils | 9 mm | |

| Achillea tenuifolia | (68) | Stems | Volatile oils | 8 mm | |

| Achillea wilhelmsii | (69) | Essential oil | 27 mm (200 μL) (for MRSAa) 19 mm (200 μL )( for MRSAa) | ||

| Achillea wilhelmsii | (70) | Methanolic extract | 19mm(400 mg/mL) | ||

| Otostegia persica | (71) | Aerial parts | Hexane extract | 11.4 mm | 10 mg/mL |

| Otostegia persica | (71) | Aerial parts | Chloroform extract | 15.4 mm | 1.25 mg/mL |

| Otostegia persica | (71) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 15.6 mm | 3.12 mg/mL |

| Otostegia persica | (30) | Aerial parts | Methanolic extract | 9.7 mm (4 mg/disc) | |

| Berberis vulgaris | (32) | Root | Aqueous extract | 8.4 mm (4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 7 mm (4 mg/disc) | |

| Berberis vulgaris | (32) | Root | Ethanolic extract | 12.5 mm (4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 15.5 mm (4 mg/disc) | 0.39 mg/mL (for clinical strain S. aureus & MRSAa) 0.04 mg/mL (for standard strain S. aureus & MRSAa) |

| Berberis vulgaris | (22) | Fruit | Methanolic extract | 17 mm | |

| Ferulago angulata | (38) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 15 µg/mL | |

| Ferula goangulata | (38) | Seeds | Essential oil | > 4 × 103 µg/mL | |

| Ferulago Bernardii | (72) | Aerial parts | Essential oil | 250 µg/mL | |

| Eucalyptus globulus | (32) | Leaves | Aqueous extract | 14 mm (4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 11 mm (4 mg/disc) | |

| Eucalyptus globulus | (32) | Leaves | Ethanolic extract | 17 mm(4 mg/disc) (for MRSAa) 15.5 mm(4 mg/disc) | 0.18 mg/mL (for clinical strain MRSAa) 0.09 mg/mL (for standard MRSAa strain) 0.39 mg/mL(for standard and clinical S. aureus strains) |

| Eucalyptus globulus | (46) | Essential oil | 10 to 30 mm (for 14 clinical MRSAa strains) 17 mm (for S. aureus) | 34.24 to 85.6 µg/mL (for 14 clinical MRSAa strains) 51.36 µg/mL (for S. aureus) |

Abbreviation: NA, no activity.

aPlants that were also evaluated against MRSA.

According to the comparison, essential oil of T. caucasicus with the MIC value of 0.31 μg/mL for S. aureus and 2.5 μg/mL for MRSA has the best inhibitory effect on S. aureus strains (Table 1). However, essential oil of T. parthenium, T. vulgaris, T. eriocalyx, T. persicus, A. millefollum, ethanolic extract of P. harmala, flower extract of H. scabrum, and ethyl acetate extract of S. urmiensis with MIC value lower than 22 μg/mL have also the acceptable inhibitory effect against S. aureus (Table 1). The antimicrobial properties the oil of Thymus species is due to phenol content. The oil of Thymus has been traditionally used as anthelmintic, bacteriostatic, antiseptic and spasmolytic agents (14, 15). Achillea species also contain a complex of different antimicrobial agents such as monoterpens, sesquiterpene lactones, flavonoids, and phenolic acids that are found most often in their oils (16-18). Therefore, displaying acceptable inhibitory effect against S. aureus was predictable in these plants. It seems the best antimicrobial effect of T. caucasicus, may be due to more phenol concentration in this species.

Flower extract of H. scabrum, collected from Charmahal va Bakhtiari was more potent than that collected from Isfahan due to its more thymol and carvacrol content (41). It is consistent with other studies that variation in environmental parameters, such as irradiance, climate, nutrients, and soil-water availability can influence plant compositions, and thus cause variation in the antimicrobial activity (73). In some herbs, variation in the antimicrobial activity was due to the plant parts used for extract preparation. For example, methanolic extract of the root from P. harmala has the best effect rather than other parts of this plant. Moreover, different extracts of herbs showed significant different antimicrobial effects in most cases. In addition, some plants showed different antimicrobial effects at different stages of their growth. In this case, Thymus pubescens, Thymus serpyllum (44), and Tanacetum parthenium (64) should be noted that during flowering stage, they had a better anti-staphylococcal effect than the pre-flowering stage. Unripe seeds of Terminalia chebula was also more active against S. aureus than ripe seeds (22).

The antimicrobial effect of methanolic extract of aerial parts of Salvia sahendica (27) and essential oil and methanolic extract from aerial parts of Salvia eremophila (29) were the same as Gentamicin on S. aureus. Moreover, the antimicrobial effect of hydroalcholic extract of Teucrium polium was higher compared to Amoxicillin, Ciprofloxacin, Vancomycin, and Imipenem (58). Surprisingly, essential oil of M. pulegium (48), Tanacetum parthenium (11), and Tanacetum pinnatum (74) showed better anti-staphylococcal effects than standard antibiotics.

Bahrami et al. determined that the antimicrobial activity of ethanolic extract from S. striata leaves is lower than Doxycyclin and Ofloxacin against S. aureus. However, these antibiotics have synergistic effects in combination with ethanolic extract of S. striata leaves (42).

Among all of the evaluated medical herbs, antimicrobial effect of 12 species, including S. tomentosa, Cuminum cyminum, Artemisia dracunulus, Artemisia herbalba, Artemisia absinthium, Thymus vulgaris, Thymus caramanicus, Mentha piperita, Peganum harmala, Achillea wilhelmsii, Berberis vulgaris, and Eucalyptus globules are also studied against MRSA. In comparison to antibacterial assays against MRSA we found that ethanolic extract of S. tomentosa, seeds of C. cyminum, A. dracunulus, A. herbalba, A. absinthium, T. caramanicus, A. wilhelmsii, ethanolic, and aqueous extract of M. piperita, root of B. vulgaris, essential oil and ethanolic extract of T. vulgaris, methanolic extract of seed, leaves, stem, root, flower and ethanolic extract of P. harmala, ethanolic extract, aqueous extract and essential oil of leaves of E. globulus have effective inhibitory effects against MRSA.

It is noteworthy that S. multicaulis (methanolic extract) was the only plant active against penicillin-resistant S. aureus. More studies concerning the molecular basis of every active extract against clinical S. aureus, especially MRSA must be performed in the future. A limitation was trouble finding the full text of some articles. We had to email the authors. Lack of response or late response of some of them caused to waste a lot of time.

6. Conclusions

Most of the evaluated Iranian plants with acceptable MIC or inhibition zone have the potency of antimicrobial activity, especially against S. aureus and its most frequent resistant strains, MRSA. So the intended natural extract, especially essential oil of Thymus caucasicus can be a candidate for drug design for replacement of conventional antibiotics with the intention treatment of S. aureus infections. However, further clinical and analytical trials of these data are necessary to finding new knowledge such as in vivo effects and side effects of using herbal extracts as antibiotics. It was also understood that extracts derived from the same species can show significant differences in antimicrobial potency when collected at different sites, owing to the influence of soil, climate, and other factors. These differences may also relate to the type of extract, using plant parts, and the stage of plant growth.