1. Background

According to the world health organization, the death rate related to cardiovascular disease (CVDs) is expected to increase by 15% globally between 2010 and 2020. Most CVDs are strongly associated with particular behavior and metabolic risk factors, including tobacco use, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, harmful use of alcohol, overweightness/obesity, raised blood glucose, and cholesterol (1). However, it has been demonstrated that the major CVDs typically occur in obese adults, especially females (WHO). Females, due to relatively less muscle mass and more body fat, are more likely to underestimate the impact of CVDs than males (2). Several studies have documented that serum lipids and lipoproteins are important indicators of CVDs development in adults (3, 4). For instance, elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) have predictive potential (5). Furthermore, other findings have demonstrated that TC/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios are other markers for CVDs (6). Recently, apolipoproteins, for example apoB, apoA-I, and especially the relationship between them (apo-ratio), have been identified as other important markers for CVDs, which is deemed at least to be more predictive (7).

ApoA-I is the major protein in HDL-C. Cholesterol within cells of the peripheral tissues through the apoA-I and eventually HDL-C is transported from blood to the liver (8). Thereby, apoA-I represents reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) and is considered as an anti-atherogenic particle. Furthermore, ApoA-I is involved in anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, producing vasodilation, anti-infectious activity, and anti-thrombotic functions (9). Thus, by measuring apoA-I, firstly, HDL-C number could be identified, and secondly additional protective effects mentioned above could be achieved (10, 11).

Moreover, apoB, a critical protein component of LDL-C, is responsible for transport of lipids from the liver and gut to peripheral tissues (9). Therefore, the total apoB level corresponds to the total number of atherogenic particles (9). Accordingly, many studies and clinical trials have been published showing that the apo-ratio is a better CVD risk factor due to the interrelation of these proteins with LDL and HDL, respectively (12).

There is also evidence suggesting that regular exercise training is an effective method to decrease and increase cardiovascular risk factors and anti-risk factors, respectively (13, 14). Chapman et al. reported that for every 1 mg/dL increase in HDL-C, the risk for CADs is reduced by 2% to 3%, and the risk of death is lowered by 6% (15). However, there are controversial reports on lipid profiles of overweight females and exercise training, which might be due to differences between type, intensity, and volume of exercise responsible for these results (16). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the effect of two exercise protocols on well-established cardiovascular risk and anti-risk factors in overweight females.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine whether in overweight females, changes of apoB, apoA-I, and apo-ratio were as much as changes in conventional lipids following 8 weeks of two types of exercise protocols, which was carried out from January 2014 to March 2014 in Abadan.

3. Methods

This study was approved by the regional scientific ethics committee, department of physical education and sport sciences of Islamic Azad University, Abadan branch. Of the overweight females, who had obtained gym membership for the first time, thirty-six overweight females (age: 46 ± 5.45 years; height: 161 ± 0.48 cm; weight: 66.67 ± 5.1 kg) were ultimately selected for the study. The sample size was calculated according to the study of Whitley and Ball (2002), which determined that a sample of n = 10 subjects for each group would provide a statistical power of over 0.80 (17). One week prior to the initiation of the study, all participants completed a medical questionnaire to evaluate their individual lifestyles and habits, for example history of health status, physical activity, smoking habits, and diet. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: untrained (lack of regular physical activity during the previous 6 months), normotensive, non-smoker, and body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 30 (kg/m2). The exclusion criteria were: BMI > 30 kg/m2, taking medication affecting lipid metabolism, absence of more than two consecutive sessions of aerobic exercises throughout the study, evidence of liver, renal, cardiopulmonary, neuromuscular and/or psychological disease, and any debilitating diseases that restrictive physical activity (14). All patients provided their written consent. Participants were randomly divided to three experimental groups including resistance exercise training (RG, n = 12), endurance exercise training (EG, n = 12) and a control group (CG, n = 12). The training groups initiated their specific physical activity (resistance or endurance) for eight weeks. Controls were asked not to change their normal habits. They were also asked not to participate in any exercise throughout the control period except light activities (e.g., walking for commuting).

3.1. Experimental Design

Endurance training: Each training session consisted of a brief warm-up (10 - 15 minutes), followed by the main exercises. Aerobic training was performed for three alternate days in a week at 60% - 75% of maximum heart rate (HR) for 8 weeks. Heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were recorded before and after the exercise in the sitting position. After the training session, cool down was also performed for 5 to 10 minutes. Maximum heart rate was calculated using the following formula (ACSM 2006): HRmax = 220-age.

Resistance training: Resistance training program was also performed for three sessions a week over a period of 8 weeks. Subjects performed resistance training with four sets of 8 to 12 repetitions at 10-RM with one-minute rest for each set. Eight different types of exercises were conducted involving abdominal curl ups, biceps curls, triceps extension, back extension, leg press, leg curl, leg extension and bench press.

3.2. Blood Samples and Analysis

Fasting venous blood samples were collected from all patients in two phases before and after the 8 weeks of the study period. Therefore, participants fasted from 10:00 pm, the evening before the blood sampling days (only water was allowed). The blood samples, which were collected from each patient, were centrifuged for 10 minutes and plasma was stored at -20°C for later analysis. Amount of blood was about 5 mL from the anterior vein of the participants’ left arm. Low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, HDL-C, TG, and TC were measured by enzymatic colorimetric kits (Pars azmoon LTD, Iran), and apoA-1 and apoB by immunoturbidimetric methods (biorexfars LTD, Iran).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

In this study, three groups were involved and tested twice. Normality of the data was checked by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (K-S test). All data were expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). Accordingly, the optimal test was One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify significant differences in mean LDL, HDL, apoA-I, apoB, TC, TG, and apo-ratio values across all groups. Student’s t-test was also conducted to observe the within group changes in the groups before and after exercise. Moreover, multiple comparisons by Tukey post hoc test were used to highlight the significant differences. The significant difference level was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software for windows (release 22 Chicago, IL, USA).

4. Results

During the 8-week intervention, all subjects participated in the full range of the supervised endurance and resistance exercise sessions and were included in the analyses. The physical characteristics of the RG, EG, and CG groups before and after the 8-week period are presented in Table 1.

| Variable | Group | Pre-Test | Post-Test | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body fat, % | CG | 32.58 ± 1.31 | 32.92 ± 1.08 | P > 0.05 |

| EG | 32.75 ± 1.05 | 32.33 ± 3.57 | ||

| RG | 32.75 ± 1.35 | 30.83 ± 1.03 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | CG | 25.81 ± 1.44 | 26.01 ± 1.56 | P > 0.05 |

| EG | 25.48 ± 1.71 | 24.77 ± 1.33 | ||

| RG | 25.67 ± 1.33 | 25.21 ± 1.17 | ||

| SBP, mmHg | CG | 121.12 ± 3.29 | 121.33 ± 2.82 | P > 0.05 |

| EG | 117.52 ± 3.31 | 118.83 ± 4.38 | ||

| RG | 123.21 ± 2.64 | 122.27 ± 4.32 | ||

| DBP, mmHg | CG | 77.62 ± 5.14 | 78 ± 2.06 | P > 0.05 |

| EG | 79.42 ± 3.16 | 79.73 ± 3.06 | ||

| RG | 81.52 ± 3.06 | 81.58 ± 3.22 |

Participants’ Physical Characteristics Across the Three Groups, Pre- and Post-Interventiona

4.1. Anthropometry and Blood Pressure

After the 8-week training programs, body fat percentage significantly decreased in RG compared to the EG and control groups (P < 0.05; Table 1). Furthermore, significant changes were found in BMI of EG and RG groups (Table 1). No significant changes were found for systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure between the groups (Table 1).

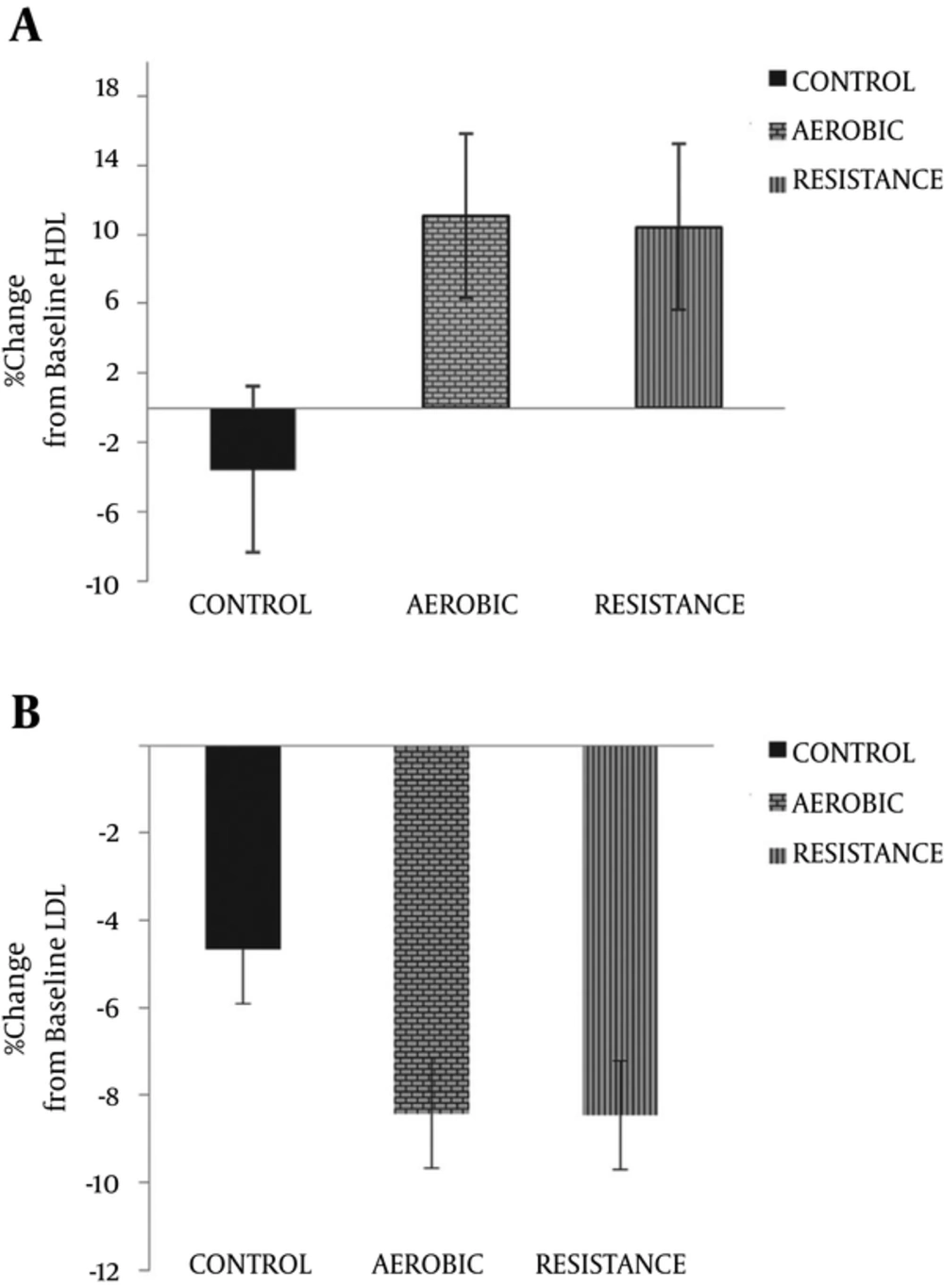

4.2. Lipid and Lipoproteins Status

The percentage change in HDL and LDL across all three training groups following 8 weeks of exercise is indicated in Figure 1. The LDL levels remained unaltered after the 8-week training period within all training groups (in %; RG: -8.46% ± 23.21; EG: -8.41% ± 21.88; CG: -4.66% ± 11.97). However, Participation in these two types of exercise training groups caused an increase in the mean HDL levels in both training groups when compared to the control group (in %; RG: 10.44% ± 10.24; EG: 11.44% ± 13.74; CG: -3.55% ± 15.08).

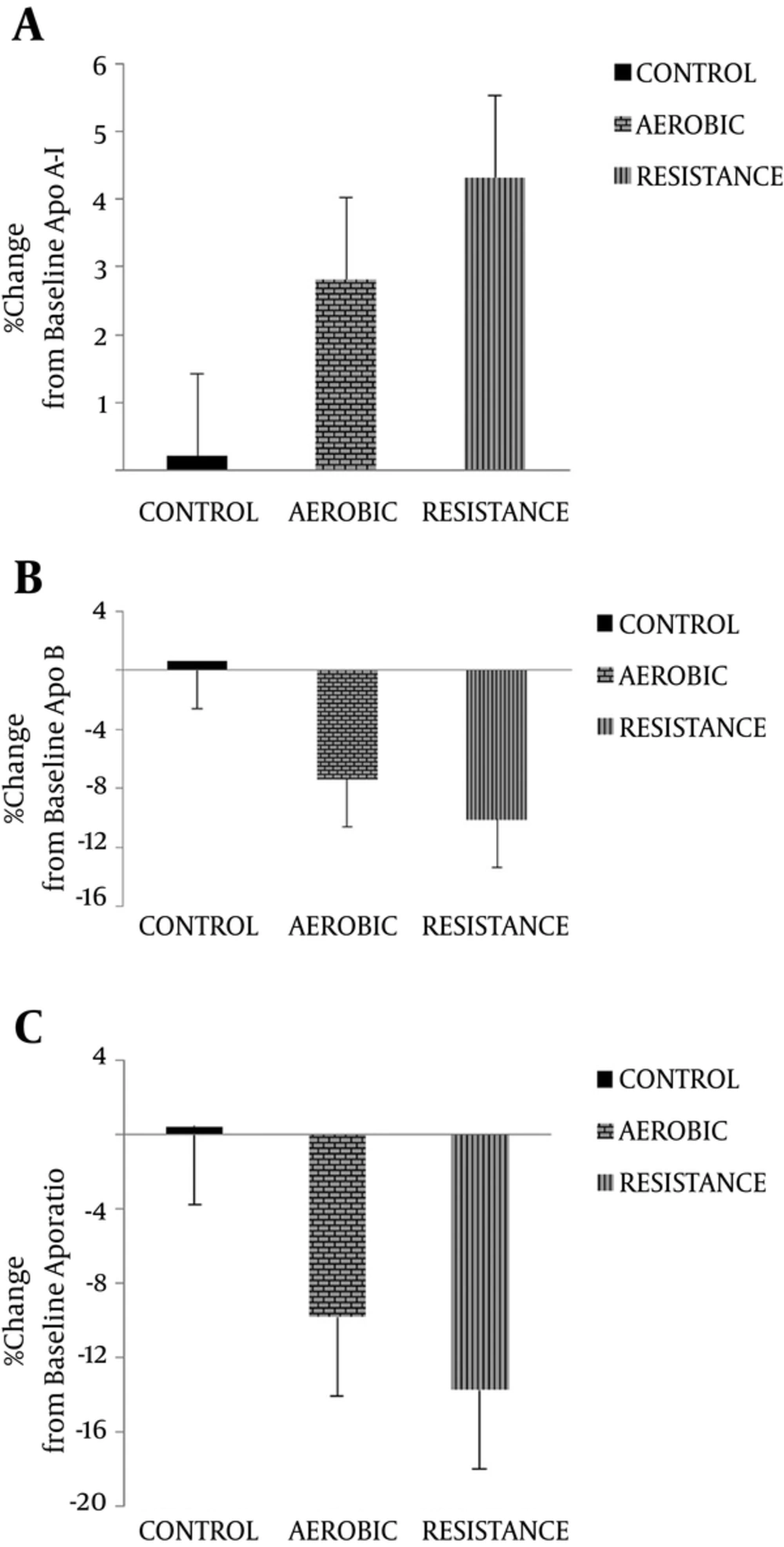

The percentage change of apoA-I levels (in %; RG: 4.32% ± 2.26; EG: 2.81% ± 2.37; CG: 0.21% ± 0.77) and apoB levels (in %; RG: -10.13% ± 2. 65; EG: -7.36% ± 3.90; CG: 0.61% ± 1. 36) indicated increases following the 8-week endurance and resistance training in both training groups compared to the control group (Figure 2). On the other hand, a significant increase in apoA-I levels and decrease in apoB levels from baseline was observed in the RG and EG groups compared to CG after 8 weeks (P > 0.05).

Apo-ratio was significantly lower in the training groups compared to the controls after 8 weeks (in %; RG: -13.82% = ± 3.22; EG: -9.84% ± 4.55: CG: 0.4% ± 1.51). Furthermore, apo-ratio was decreased within RG and EG groups following participation in 8 weeks of exercise training; however, apo-ratio was increased within CG.

The percentage change of the other variables is shown in Table 2. Both training protocols had significant effect on the mean TC (-14.53% ± 19.81) and TG (-17.49% ± 13.64) levels of EG following 8 weeks of the exercise training program; whereas, these variables did not alter significantly in RG and CG after 8 weeks of exercise training.

| Variable | Group | Pre-Test | Post-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDL-C, mg/dL | CG | 46.25 ± 6.35 | 44.33 ± 7.82 |

| EG | 40.67 ± 4.89 | 44.83 ± 4.38 | |

| RG | 43.88 ± 12.04 | 48.27 ± 7.32 | |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | CG | 102.17 ± 28.24 | 96 ± 42.06 |

| EG | 98.52 ± 35.35 | 86.73 ± 30.06 | |

| RG | 86.83 ± 1853 | 78.58 ± 33.22 | |

| TG, mg/dL | CG | 115.25 ± 31.04 | 111.67 ± 13.2 |

| EG | 127.17 ± 73.92 | 116.37 ± 12.5 | |

| RG | 125.42 ± 60.57 | 120.17 ± 7.81 | |

| TC, mg/dL | CG | 180 ± 30.13 | 174.42 ± 22.1 |

| EG | 170.5 ± 38.18 | 146.25 ± 38.2 | |

| RG | 161.67 ± 20.32 | 149.91 ± 33.2 | |

| Apo A-1 | CG | 149.25 ± 2.51 | 149.58 ± 2.51 |

| EG | 150.21 ± 3.23 | 154.46 ± 5.32 | |

| RG | 150.64 ± 3.39 | 157.14 ± 4.25 | |

| Apo B | CG | 79.79 ± 3.39 | 80.25 ± 2.81 |

| EG | 80.87 ± 2.40 | 74.86 ± 2.77 | |

| RG | 81.05 ± 2.66 | 72.81 ± 2.13 | |

| Aporatiob | CG | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.02 |

| EG | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 0.48±0.02 | |

| RG | 0.53 ±.02 | 0.46±00.018 |

Mean Values of Cardiovascular Disease Risk and Anti-Risk Factors Among Adolescentsa

5. Discussion

The main findings of the current study were significant changes in mean HDL, apoA-I, apoB, and apo-ratio levels with two types of training along with markedly decreased mean TC and TG levels only in EG after 8 weeks of the intervention. Longitudinal follow-up studies of the patients with CVDs have demonstrated that there are likely declines in lipid profiles following training program (18). In the present study, it was seen that following 8-week exercise programs, the mean apoA-I levels significantly increased as well as HDL-C in EG and RG. In addition, apoB and the apo-ratio had also significant decreased in two experimental groups. These findings were consistent with the studies of Holm et al. (2007) (19), Heitkamp et al. (2008) (20) and Bijeh et al. (2015). Bijeh et al. reported that 8 weeks of aerobic training program decreased apoB, apoA-I, and aporation levels in overweight females (21). Holm et al. (2007) also reported that the levels of apoB and apo-ratio were significantly decreased after training in overweight healthy males, according to the results of a 1-year Oslo diet and exercise study (19). In contrast to our findings, the study by Giada et al. (2000) and Von Stengel et al. (2004) did not show such effects (22, 23).

Reasons for the variable apolipoprotein responses to aerobic and resistance exercise training may be due to factors such as frequency, intensity, duration of the protocols and body composition changes of the participants in the current study. Previous studies have reported that high intensity exercise training may improve lipoprotein levels (24).

In the present study, body mass index (BMI) and body fat percentage were also altered following 8 weeks of both exercise programs in our experimental groups compared to CG. The result of our study was consistent with that of koozehchian et al. (2014), which showed favorable alterations in BMI and body fat percentage levels following specified periods of exercise training (4). Most researchers and guidelines have also reported that BMI and body fat percentage are often associated with CVDs and reduction in their levels may improve lipoprotein profiles (25, 26). For instance, Holme et al. (19) and Ben Ounis et al. (12) exhibited the same findings.

The results of this study showed that HDL-C levels increased markedly after two type of training programs. In line with our study, there are some other studies that have reported a positive correlation between exercise training and increased apoA-I and HDL-C levels (4, 7).

In a study by Blumenthal et al. (1991), it was reported that females have lower HDL-C levels at baseline than males (27), which is partially explained by the significant increase in HDL-C levels in our overweight females (28). However, in contrast to our findings, Bijeh et al. did not show such effects (21).

In contrast to the increase of HDL-C, the mean LDL-C level was not changed in our groups after 8 weeks of interventions. Since the mean apoB levels deceased significantly, we expected to have LDL-C at lower levels, but this did not occur. Hence, it seems that apoB is a more sensitive and useful predictor of risk of CVDs, especially for those with low values of LDL-C. In a cross sectional study, in a low-risk Korean population, Kim et al. (2005) reported that in the lowest quartile of TC, TG and LDL-C, and the highest quartile of HDL-C, only the apo-ratio was associated with CAD in both males and females (29). However, in contrast to this finding, Grandjean et al. (1998) reported a significant increase in apoB concentrations after 12 weeks of exercise training (30). Accordingly, increased levels of HDL-C and apoA-I, and decreased apoB and aporatio in our experimental groups may suggest that the two selected protocols were sufficient, which could partially reduce the CVDs risk in these overweight females. However, in the present study, exercise programs of either resistance or endurance had no effect on TC levels in our overweight subjects. This outcome is contrary with the results of the study conducted by Katzmarzyk et al., and Lokey and Tran (31, 32). However, a significant decrease in TG following 8 weeks of aerobic exercise was exhibited in EG when compared with the other groups, yet previous studies believed that decreased levels of TG cannot be attributed solely to weight reduction (33) and there is a mechanism that has induced a reduction in TG concentration, which is not clear yet (34). Thus, further studies are needed to investigate the effect of exercise on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in overweight females. The present study had several limitations. First, the researcher had to determine the caloric expenditure to determine changes in plasma lipid and lipoproteins of overweight females, which may have affected the results. Secondly, when studying obese individuals, it is important to consider distinction of obesity. Less visceral abdominal fat is associated with normal lipid and lipoprotein profile (35). Thirdly, it is important to ascertain the phases of the menstrual cycle during testing periods to reduce the influence of hormones on plasma lipid and lipoprotein analysis. Nevertheless, such results suggest that physical activity with proper intensity and time might partially improve the obesity index along with cardiovascular risk factors.

5.1. Conclusion

According to the results of the present study, which was carried out from January 2014 to March 2014 in Abadan, apos and apo-ratio are at least as good as lipids and lipid ratios. Thus, apos and the apo-ratio are suitable if they are considered as predictors for CVDs.