1. Background

The administration of antibiotics has raised concerns about the development of zoonotic bacterial resistance in animals, which has resulted in foodborne illnesses in several countries. Probiotics are one of the few alternatives to these medications. They not only promote protective effects against infections but also produce healthy foods (1). In aquaculture systems, a variety of microbial strains are utilized as probiotics. The common probiotics found in aquaculture are Lactobacillus spp., Bacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Vibrio spp., Saccharomyces spp., Enterococcus spp., and Bacillus subtilis (2). Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) are everywhere in nature and can be found in soil, water, plants, and animals. Several genera of LAB do not form a monophyletic group; rather, they should be viewed as a heterogeneous group that functions biologically. The lactic fermentation of LAB produces different substances, including organic acids, diacetyl, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocin or bactericidal proteins (3). A developing area of probiotic research involves using LAB in the aquaculture industry (4-8).

Numerous freshwater teleosts have been studied for their probiotic activity, including the Chinese carps (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix and Ctenopharyngodon idella), common carp (Cyprinus carpio), Mosambic tilapia (Oreochromis mossambica), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), walking catfish (Clarias batrachus), murrel (Channa punctatus), and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (9-12). In most studies, only a single probiotic species has been used and evaluated, while the potential synergistic effects of multiple probiotic species have received less attention. It should be noted that fish behavior and reactions to environmental stimuli in ponds differ from those in laboratory and aquarium settings.

2. Objectives

The present work aimed to evaluate the effect of the multispecies probiotic combination on growth performance, biochemical indices, and immune responses of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) in ponds.

3. Methods

3.1. Rearing Conditions

Fish were purchased from a local fish farm in Shoushtar City, Khuzestan Province, then transported to earth ponds. The fish were randomly divided into four equal groups. The feeding trial was performed in four groups (treatments 1, 2, and 3 and control). Probiotics were not included in the Control group’s diet (The basal diet composition is shown in Table 1). Diets with various viable probiotic combination concentrations of 5×106, 5×107, and 5×108 CFU g-1 were provided as treatments 1, 2, and 3 during the experiment, respectively. Throughout 180 days, the fish were fed thrice daily at a rate of 5% of their body weight.

| Proximate Composition | % Wet Weight |

|---|---|

| Crude protein | 37 |

| Crude fat | 9 |

| Crude ash | 4.2 |

| Gross energy (MJ kg-1) | 3455 |

| Moisture | 8 |

3.2. Preparation of Probiotic Suspensions

In this study, the probiotics Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus isolated from the gut of T. grypus were used. To prepare lactobacillus bacteria and add them to fish food, each bacterium was cultured separately in MRS broth under anaerobic conditions. The bacteria were harvested to centrifuge at 3,000 g (10°C) for 30 min, washed twice with normal saline (0.1 M, pH 7.2), and re-suspended in the normal saline to achieve an absorbance of 0.132 at 600 nm (0.5 McFarland Standard). The required amount of bacterial suspension was slowly sprayed into the diet while mixing it in parts under sterile conditions. Then, the diet was dried in an oven at 30°C for 18 h and stored at - 20°C until use. Only sterile physiological saline was sprayed on the food of the control group (13).

3.3. Growth Performance

Growth performance was determined by body weight growth (BWG), condition factor (CF), feed conversion ratio (FCR), specific growth rate (SGR), and protein efficiency ratio (PER).

3.4. Sample Collection

On days 0, 90, and 180 after the start of the trial, blood samples were collected. The serum was separated from the remaining blood by centrifugation (3.000 g, 10 min, 4°C) after an aliquot of the collected blood was placed in a microtube that had been heparinized. Before usage, the sera were then frozen at - 80°C.

3.5. Non-specific Immune Parameters

3.5.1. Serum Lysozyme Activity

To measure lysozyme activity in serum, a turbidimetric test was carried out using lyophilized Micrococcus lysodeikticus (Sigma-Aldrich) (14). This was accomplished by combining 15 µL of serum sample with 135 µL of M. lysodeikticus at a concentration of 0.2 mg mL - 1 (w/v) in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (SPB), pH 5.8 (Sigma-Aldrich). The SPB was used as a negative control in place of serum. A unit of lysozyme activity was established as the volume of serum that caused a 0.001 per minute decline at 450 nm at 22°C (13).

3.5.2. Serum Bactericidal Activity

Using a previously described method, serum bactericidal activity was assessed (15). With 0.1% Gelatin-veronal Buffer (GVBC2) (pH 7.5, containing 0.5 mM Mg2+ and 0.15 mM Ca2+), sera samples were diluted three times. The same buffer was used to suspend A. hydrophila (standard code number AH04) to a concentration of 1 × 105 CFU mL-1. The bacteria and diluted sera were combined 1: 1, incubated for 90 minutes at 25°C, and then shaken. The same buffer-containing control tubes were incubated for 90 minutes at 25°C. The number of live bacteria was then determined by counting the colonies formed from the resulting mixture after 24 hours of incubation on TSA (Tryptic Soy Agar) (Merck, USA) plates. The percentage of colony-forming units in the test group compared to the control group represented the test serum’s bactericidal activity.

3.5.3. Complement Activity Assay

Using rabbit red blood cells (RaRBC) as the complement’s target, the alternative complement activity (ACH50) was measured. The RaRBCs were placed in 1.5% agar (pH 7.2), 75 mL MgCl2, and 150 mL CaCl2 in 100 mL Phosphate-buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.0). Cell concentration was adjusted to 1 × 108 cell ml-1 after centrifuging the RaRBC suspension at 750 g for 5 min while washing it with PBS. In a plate, 12 mL of Agarose containing RaRBC was distributed, incubated at 4°C, and holes were punched (3 mm diameter). The diameter of the lysis was measured after each hole was filled with 20 μL of blood sample and left at room temperature for 48 hours (13, 16, 17).

3.6. Serum Biochemical Parameters and Hepatic Enzymes Activity

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the quantities of biochemical parameters and activity of hepatic enzymes (Pars Azmoon Co., Tehran, Iran) were determined using spectrophotometry (Unico, UV-2802S; Shanghai, China). Using the previously published standard procedures, the concentrations of these parameters were measured (18, 19).

3.7. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS software version 22, and the results were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine whether all the data were normally distributed. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test were used to determine whether the mean values of the tested parameters differed. When differences were P < 0.05, they were considered significant.

4. Results

4.1. Growth Performance

The growth performance results are shown in Table 2. During the experimental period, the highest daily growth rate was observed in treatment 3. This parameter significantly differed between the control group and other probiotic treatments (P < 0.05). Also, the specific growth factor was influenced by probiotic treatments significantly (P < 0.05). The food conversion factor showed that treatment 3 had the lowest rate among the experimental treatments (P < 0.05).

The condition factor in common carp fed with different probiotic concentrations showed a significant increase in treatments 2 and 3 compared to the other two groups (P < 0.05). The protein efficiency ratio during 6 months showed that treatment 3 was the best among other groups (P < 0.05).

| Diets | BWG | CF | SGR | FCR | PER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 19.66 ± 1.12c | 3.25 ± 0.06c | 3.09 ± 0.06c | 2.68 ± 0.31a | 1.5 ± 0.27b |

| Treatment 1 | 21.72 ± 1.07b | 3.39 ± 0.07b | 3.41 ± 0.05b | 2.51 ± 0.37a | 2.24 ± 0.42a |

| Treatment 2 | 23.81 ± 1.97b | 3.65 ± 0.11b | 3.7 ± 0.06b | 2.18 ± 0.25ab | 2.68 ± 0.75a |

| Treatment 3 | 25.64 ± 1.16a | 3.77 ± 0.18a | 3.94 ± 0.15a | 1.73 ± 0.27b | 2.59 ± 0.11a |

1 The values were expressed as mean ± SD.

2 For each parameter, different small letters denote significant (P < 0.05) differences between the values in each column.

4.2. Immune Responses

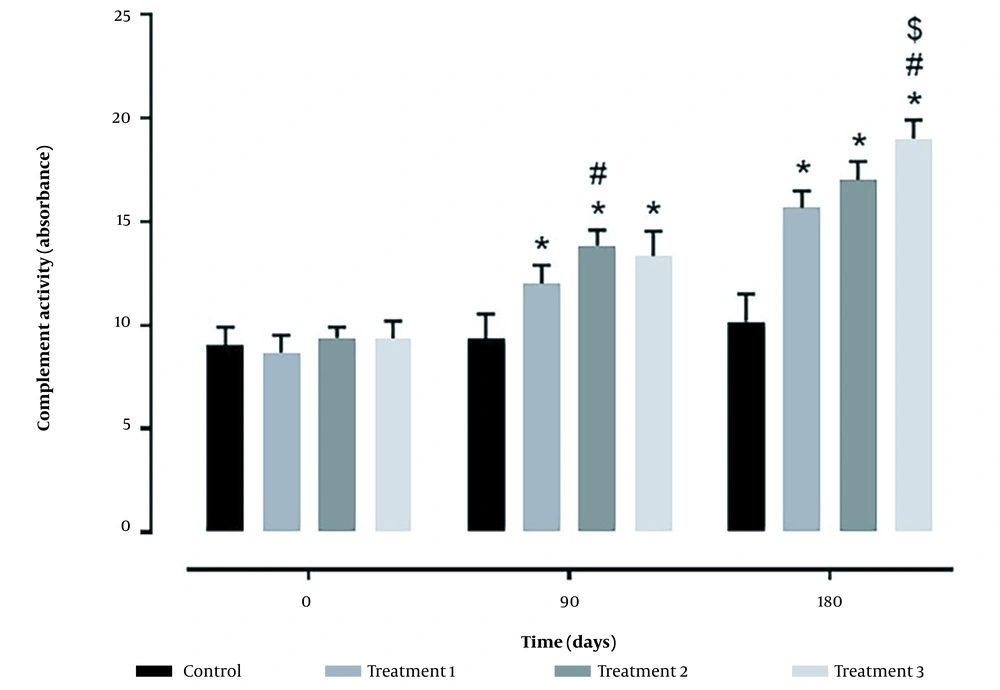

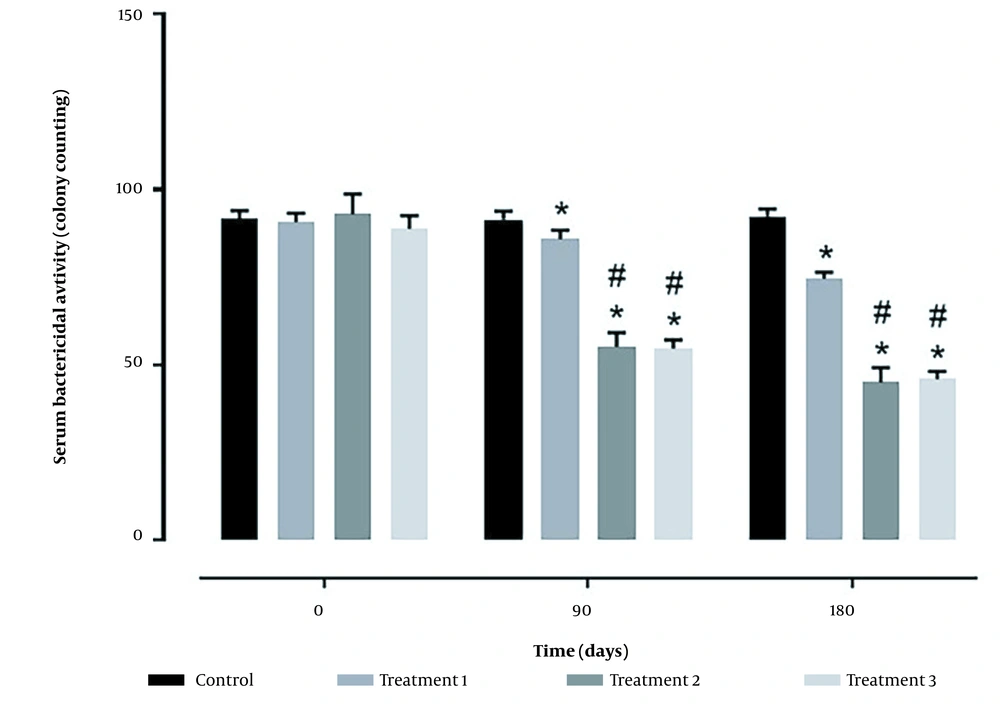

Complement activity and serum bactericidal activity in treatment groups increased depending on the days of feeding with probiotics. In both parameters, treatments 2 and 3 had a better situation than treatment 1 and the control group (Figures 1 and 2).

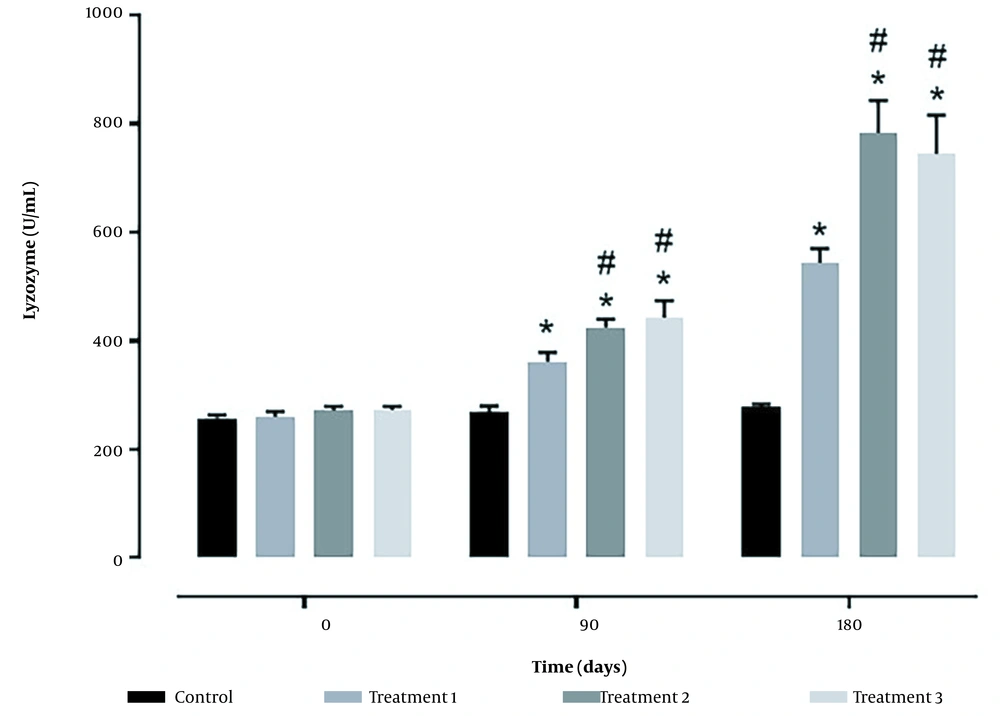

Serum lysozyme activity (Figure 3) showed the highest level in treatments 2 and 3, significantly different from other groups (P < 0.05).

4.3. Serum Biochemical Parameters and Hepatic Enzymes Activity

Table 3 displays the blood biochemical parameters. The results showed no significant difference between the probiotic treatments and the control group regarding serum glucose. Serum cholesterol was significantly lower in probiotic treatments, and the highest was observed in the control group (P < 0.05). This was the same for triglycerides, whose levels differed significantly between the probiotic treatments and the control group (P < 0.05).

| Parameters and Experimental Groups | Day 0 | Day 90 | Day 180 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | |||

| Control | 25.4 ± 2.65A, a | 24.9 ± 2.04 A,a | 26.07 ± 1.52 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 25.24 ± 2.54 A,a | 26.29 ± 3.26 A,a | 24.95 ± 3.86 A,a |

| Treatment 2 | 25.1 ± 2.88 A,a | 26.97 ± 3.03 A,a | 24.75 ± 1.31 A,a |

| Treatment 3 | 25.79 ± 2.44 A,a | 25.89 ± 2.1 A,a | 25.19 ± 2.57 A,a |

| Cholesterol | |||

| Control | 103.2 ± 3.2 A,a | 103.1 ± 2.99 A,a | 102.4 ± 1.93 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 102.4 ± 2.7 A,a | 95.85 ± 2.42 B,b | 84.59 ± 1.7 C,b |

| Treatment 2 | 103 ± 2.18 A,a | 91.76 ± 1.63 B,b | 80.02 ± 1.4 C,c |

| Treatment 3 | 103 ± 1.46 A,a | 84.87 ± 1.42 B,c | 75.17 ± 2.32 C,d |

| Triglyceride | |||

| Control | 125.86 ± 4.18 A,a | 125.91 ± 3.33 A,a | 127.04 ± 4.3 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 126.43 ± 3.54 A,a | 119.15 ± 3.66 B,b | 105.69 ± 5.67 C,b |

| Treatment 2 | 125.86 ± 3.59 A,a | 104.87 ± 2.98 B,c | 88.56 ± 4.00 C,c |

| Treatment 3 | 126.52 ± 3.16 A,a | 95 ± 3.97 B,d | 86.88 ± 4.37 C,c |

| Total protein (g dL-1) | |||

| Control | 2.72 ± 0.14 A,a | 2.84 ± 0.02 A,c | 2.53 ± 0.06 A,c |

| Treatment 1 | 2.5 ± 0.07 C,a | 3.24 ± 0.14 B,b | 3.64 ± 0.2 A,b |

| Treatment 2 | 2.72 ± 0.16 C,a | 3.44 ± 0.34 B,a | 4.92 ± 0.16 A,a |

| Treatment 3 | 2.85 ± 0.03 C,a | 3.9 ± 0.04 B,a | 5.13 ± 0.29 A,a |

| Albumin (g dL-1) | |||

| Control | 1.56 ± 0.16 A,a | 1.39 ± 0.18 A,a | 1.51 ± 0.16 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 1.56 ± 0.07 A,a | 1.64 ± 0.2 A,a | 1.63 ± 0.31 A,a |

| Treatment 2 | 1.5 ± 0.08 A,a | 1.47 ± 0.15 A,a | 1.4 ± 0.39 A,a |

| Treatment 3 | 1.54 ± 0.04 A,a | 1.53 ± 0.22 A,a | 1.52 ± 0.32 A,a |

1 The values were expressed as mean ± SD.

2 For each parameter, small and capital letters indicate different comparisons. Different small letters denote significant (P < 0.05) differences between the values in each column. Different capital letters represent significant (P < 0.05) differences between the values in each row.

Fish given probiotic supplements had considerably more serum total protein than fish given the standard diet (P < 0.05). During the investigation, there was no significant difference in the amount of albumin between the probiotic treatment groups and the control group (P > 0.05).

After 60 and 180 days of feeding with the experimental diets (Table 4), significantly lower levels of ALT and LDH were observed in treatment 2 than in the control group (P < 0.05). No remarkable alteration in serum ALT was observed in treatment 3 after feeding with experimental diets for 90 days. However, after 180 days, this level was significantly lower than in treatment 1 and the control group (P < 0.05).

| Parameters and Experimental Groups | Day 0 | Day 90 | Day 180 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AST (U L-1) | |||

| Control | 14.57 ± 1.18 A,a | 14.9 ± 2.04 A,a | 15.91 ± 1. 2 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 14.57 ± 2.21 A,a | 13.62 ± 0.88 A,a | 14.62 ± 1.4 A,a |

| Treatment 2 | 14.26 ± 1.83 A,a | 13.13 ± 1.38 A,a | 12.08 ± 1.2 A,b |

| Treatment 3 | 14.46 ± 1.88 A,a | 12.72 ± 1.45 A,a | 12.53 ± 1.51 A,b |

| ALT (U L-1) | |||

| Control | 25.49 ± 2.34 A,a | 25.73 ± 1.71 A,a | 24.37 ± 2.75 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 24.91 ± 2.86 A,a | 23.68 ± 1.98 A,b | 24.59 ± 1.7 A,b |

| Treatment 2 | 24.67 ± 2.6 A,a | 21.76 ± 1.63 B,b | 19.51 ± 1.28 B,c |

| Treatment 3 | 24.23 ± 1.87 A,a | 23.97 ± 2.33 A,c | 18.91 ± 1.72 B,d |

| ALP (U L-1) | |||

| Control | 85.72 ± 3.94 A,a | 85.39 ± 3.54 A,a | 85.6 ± 3.75 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 86.56 ± 4.17 A,a | 83.74 ± 2.1 A,a | 83.36 ± 2.59 A,a |

| Treatment 2 | 85.83 ± 4.34 A,a | 83.97 ± 3.18 A,a | 84.23 ± 2.82 A,a |

| Treatment 3 | 86.54 ± 4.64 A,a | 83.53 ± 3.22 A,a | 83.36 ± 3.11 A,a |

| LDH (U L-1) | |||

| Control | 28.2 ± 2.36 A,a | 26.91 ± 2.87 A,a | 25.37 ± 3.8 A,a |

| Treatment 1 | 28.1 ± 1.93 A,a | 25.82 ± 3.18 AB,a | 24.02 ± 2.7 B,a |

| Treatment 2 | 27.53 ± 1.75 A,a | 23.2 ± 2.62 B,a | 23.56 ± 2.67 B,a |

| Treatment 3 | 28.19 ± 2.05 A,a | 23.33 ± 1.39 B,a | 23.54 ± 3.73 B,a |

1 The values were expressed as mean ± SD.

2 For each parameter, small and capital letters indicate different comparisons. Different small letters denote significant (P < 0.05) differences between the values in each column. Different capital letters denote significant (P < 0.05) differences between the values in each row.

5. Discussion

The present study showed an improvement in daily growth rate, specific growth rate, protein efficiency, and condition factor in fish treated with probiotics compared to the control group. Also, the food conversion ratio in the treatments was significantly reduced compared to the control group. According to Lara-Flores et al., all probiotic-rich diets promoted growth in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) compared to the control group (20). They explained how adding probiotics reduces the effects of stressors and feeding fish a diet containing yeast improves their growth and performance. Similar results were observed with yeasts and probiotics, proving their positive effects on saltwater fish (21-23).

Concerning immune responses, this study assessed complement activity, lysozymes, and serum bactericidal activity. Concerning complement activity, all probiotic groups had better conditions than the control group, although the highest activity was observed in treatment 3. Similar results were obtained regarding lysozymes and serum bactericidal activity, and all probiotic treatments had better conditions than the control group. However, the values obtained in treatments 2 and 3 were not significantly different.

Fish immune system performance has been investigated since the 1980s in relation to dietary components and food additives. Research has been done on some of these supplements to see if they can protect fish from stress and disease (24). One of the probiotics’ most significant positive impacts is improved immune system performance. Fish can produce more lysozyme, xenophagy, and a variety of cytokines when given single or multispecies probiotics. Additionally, probiotic bacteria can boost immunoglobulin cells and acidophilic granulocytes and stimulate the gut immune system in fish. The immune-stimulating properties of probiotics can be significantly influenced by several factors, including their source, kind, quantity, and duration (25).

The use of probiotic bacteria in aquaculture is increasing. According to extensive studies on probiotics, they positively affect the serum biochemical factors of fish. However, the present study showed that probiotics in the diet of common carp did not cause a significant change in glucose levels compared to the control group. Therefore, probiotics did not reduce blood glucose compared to the control group.

Serum protein is also a relatively unstable biochemical index that changes under the influence of external and internal conditions (26). The increase in serum protein levels is considered a suitable indicator to check the health status of fish. Changes in serum protein levels have been reported in many studies following the use of immunostimulants, probiotics, and prebiotics (27). The current study demonstrated that after consuming experimental diets, the experimental groups significantly decreased total serum protein levels on sampling days compared to the control group. However, there was no significant change in the amount of albumin, which suggests that there may have been an increase in the levels of other proteins.

Cholesterol plays an important role in the cell membrane’s structure and the biosynthesis of some hormones. In the present study, a significant decrease was observed between experimental treatments compared to the control group. The hematological and biochemical profile of fish serum was studied to determine the effects of feeding them with immunogen after probiotic fermentation. The study found that metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, were produced in the digestive system of monogastric animals like fish. These metabolites were then transported to the liver through the bloodstream, where they reduced cholesterol synthesis. The results of this study were consistent with these findings (28). Concerning triglyceride, a significant decrease was observed in the treatments fed with the probiotic combination compared to the control group.

Bajelan et al. in 2017 showed that the use of synbiotics in the benny fish diet with different concentrations led to a significant reduction in low-density cholesterol and triglycerides compared to the control group, which was consistent with other treatments in the current study (29).

As known, ALT, AST, and ALP enzymes are important in determining fish health status. Liver cells are rich in enzymes, and Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) is also used to investigate liver tissue damage (30). This research showed that the AST level was not significantly different between the probiotic treatments and the control group. Regarding ALP, no significant difference was observed between the treatments. Regarding the activity of ALT and LDH enzymes, a significant decrease was observed in probiotic treatments compared to the control group after consuming a diet containing probiotics. This shows that probiotics, especially when used simultaneously, can decrease liver enzyme activity, including alkaline phosphatase. Hence, probiotics can somewhat improve liver and kidney activity.

5.1. Conclusions

The multispecies probiotic combination, isolated from the intestine of Shabout, at concentrations of 5 × 107 CFU g-1 and 5 × 108 CFU g-1 of food, can positively affect the growth performance, immune system, and biochemical parameters of common carp. Since there was no significant difference in most of the results obtained, the lower concentration of 5 × 107 CFU g-1 is preferred.