1. Background

Megavoltage electron beams are used for radiation treatment of shallow and superficial tumors. The source-surface distance (SSD) is one of the required parameters to calculate the output factor and dose distribution for these electron beams, and its assessment requires knowing a point as the electron source. Unlike photon beams, electron beams do not originate from a specified physical source (such as a target in photon beam radiotherapy) of the accelerator’s head. The produced electron beam passing through different components of the Linac head becomes divergent, and this creates the impression that it is generated from a single point. By back projection of the movement path of electrons along the patient surface, one can define the virtual electron source (1).

Several ways have been suggested to determine the virtual electron source. By imaging the copper grids or plates containing circular holes at various distances from the collimator and by back projection of the images of grid blades or cavity walls, their point of intersection can be regarded as a virtual source (2). The use of a virtual SSD for estimating the output factor in different SSDs can only be acceptable for the large field sizes, as for small field sizes this method gives the wrong estimated values (3). The concept of effective SSD (SSDeff) was originally proposed by Khan et al. (1978). It makes the use of the SSD factor acceptable for calculating the output factor for different gaps between the therapeutic surface and the end of the electron applicator, by measuring the depth of the maximum dose (4).

By applying corrections resulting from the SSDeff method for electron beams, Johnson et al. (1994) have shown that hot and cool spots are acceptable in terms of clinical applications (3). Xu et al. (2005) assessed the effect of different scattering conditions around different positions of the dosimeter (in the air, on the surface of the water, and the maximum depth in solid water) on the SSDeff (5). Al Asmary et al. (2010) reported the dependency of the SSDeff on the field size and electron beam energy. The estimated SSDeff for the standard applicators can be used to calculate the designed shield for electron beams (6).

Usually, incorrect estimation of output factors for SSDs different than SSD = 100 cm is one of the main sources of error when calculating dose distribution during electron therapy in radiotherapy applications. An individual tabulation of SSDseff as function of energy, depth, and field size is necessary to calculate dose distribution during clinical situations.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study is to determine the SSDseff of electron beams from a Varian 2100 CD Linac (established in the radiotherapy department of Golestan Hospital, Ahvaz, Iran) as a simple analytical equation, and to estimate its dependency on beam energy and water phantom depth.

3. Materials and Methods

A Varian Linac 2100CD with energies of 4, 6, 9, 12, and 15 MeV and an electron applicator with a size of 20 × 20 cm2 were used to dose measurements. Nominal SSDs of 97, 100, 105, 110, and 113 cm with air gaps of 2, 5, 10, 15, and 18 cm between the end of the applicator and the water phantom surface were applied. All dose measurements were carried out using Farmer ionizing chambers with a sensitive volume of 0.13 cc in the water phantom (50 cm3), a PTW-Blue Phantom with Perspex walls. A Scanditronix Wellhofer dosimetry system and Omnipro software (version 6.4) were used for dose readings. Each measurement was repeated at least three times to maintain repeatability and to ensure the stability of the output of the system.

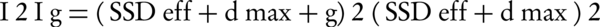

Unlike what was supposed by Khan et al. (1978), a zero air gap (g = 0) is not possible on the Varian Linac 2100CD accompanied by an electron applicator due to structural limitations. Doses are measured in a phantom at the depth of maximum dose (dm), with the phantom first at the standard SSD (with 2 cm air gap, g = 2 cm) and then at various distances up to 18 cm from the applicator end. Suppose I2 = a dose with g = 2 cm and Ig = a dose with gap g between the standard SSD point and the phantom surface. Then, using the inverse square law:

Equation 1.

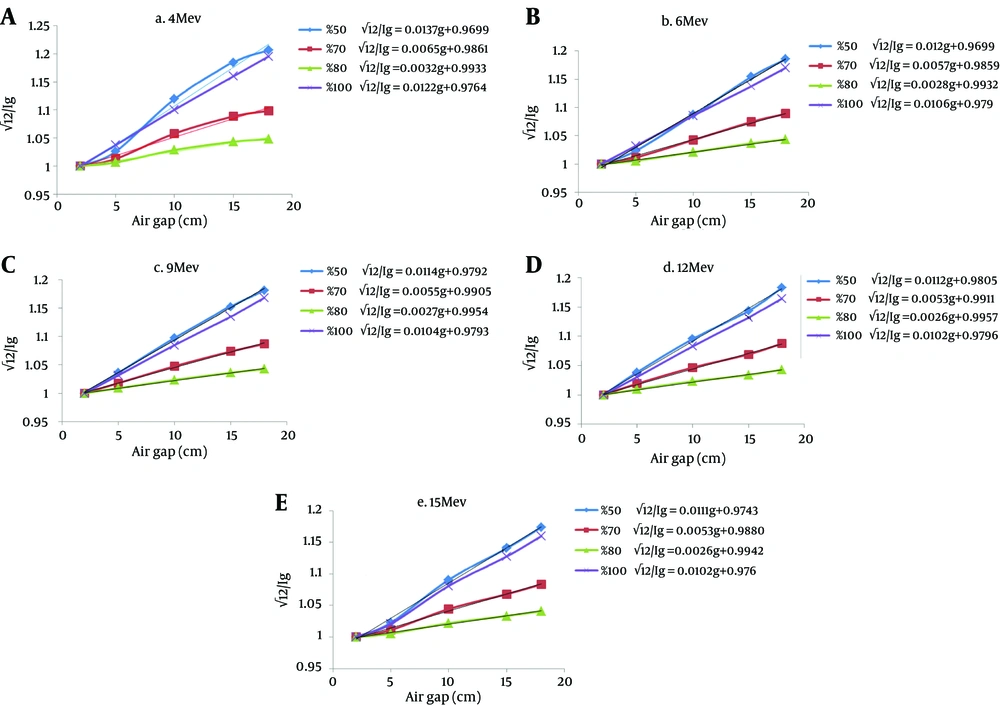

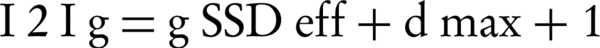

By plotting √(I2/Ig) as a function of gap g, a straight line is obtained with a slope of:

Finally, the effective SSD is given by:

In addition to determining the SSDeff at a depth of maximum dose, the SSDseff values were drawn for the different depths extracted from the PDD curve of the Omnipro software, and their changes for the various energies and the depths were evaluated. The maximum error of average dose measurements in any depth after at least three repetitions was less than 5%.

4. Results

Using the inverse square law and by applying the various air gaps, the amount of √(I2/Ig) for energies of 4, 6, 9, 12, and 15 MeV for the 20 × 20 cm2 electron applicator were measured. As shown in Figure 1, √I2/Ig increases almost linearly with increase of the air gap’s height, except for the 50% PDD of 4 MeV. These fluctuations are expected due to the high dose gradient of low-energy beams at shallow depths with lower %PDDs. The slopes of these lines were extracted to calculate SSDseff (Table 1).

| Depth, SSDeff | Energy, MeV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | |

| 100% PDD | 79 | 91 | 92 | 93 | 92 |

| 50% PDD | 70 | 79 | 82 | 83 | 82 |

| 70% PDD | 73 | 85 | 86 | 88 | 87 |

| 80% PDD | 76 | 85 | 88 | 89 | 87 |

5. Discussion

Electron beams, unlike photon beams, do not emanate from a physical source of a Linac’s head. Calculation of output factors and curves of the dose distributions resulting from the accelerator in radiotherapy applications requires determining the source of electron beam. Table 1 shows the dependency of SSDeff with measurement depth in phantom, and the energy of the electron beam. At a depth with a certain PDD, by increasing the energy the SSDeff is increased, and likewise increases by increasing PDD at related to a particular depth a distinctive energy. These results are consistent with the results reported by others (2, 7).

Ostwald et al. (1996) reported that effective source-surface distances (ESSD) varied with depth and energy of the electron beam. The surface ESSD varied from 68 cm for 4 MeV to 82 cm for 16 MeV, but increased with depth to a maximum value, which was found at approximately half the practical range (Rp) (7). The use of less PDD and less energy causes lower SSDeff values. Changes in SSDeff for energies higher than 6 MeV are not noticeable. This indicates that for the exact dose calculation using electron beams of lower energies like 4 MeV, the related SSDeff has a lot of differences from that in the higher energies. As reported by Rajasekar et al. (2002), the rapid reduction of dose due to the applicator-scattered component with an extended SSD was significant for the lower energies (8).

The average difference of SSDeff (for all the energies using PDD of 50%, 70%, and 80%) in comparison with the PDD of 100% was about 12%, 6%, and 5%, respectively which is not acceptable for calculating SSDeff. These differences are mainly caused by decreased output at smaller depths. A difference of 31 cm between the surface ESSD and the maximum ESSD (for the SSDs of 100 - 130 cm and for the 20 MeV beam in the 6 × 6 cm2 field) was reported by Ostwald et al. (1996) (7). Hence, in agreement with their result, the SSDeff calculated at the maximum dose depth (Dmax) may be used with reasonable accuracy for calculating the dose in the therapeutic range.

The amount of SSDeff is dependent on energy and the depth of the selected PDD. At a given energy by changing the depth of the selected PDD, the SSDeff shows considerable change. By using the PDD in the depth of maximum dose, the required SSDeff can be calculated by applying the inverse square law.