1. Background

Obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common disorder with a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 3% in children and adolescents (1). It is characterized by persistent, unwanted, and useless disturbing/intrusive thoughts, images, and urges (obsessions), repetitive behaviors, or mental acts (compulsions) (1, 2). It usually runs a chronic course with waxing and waning variations and can cause pervasive impairments in multiple domains of life (1-4). Although the prevalence rate is the same in both genders, males are more prone to OCD in their prepubertal age (1, 5). Due to the developmental stages, the symptom presentations are usually heterogenous in children and adolescents, with variations in presentations in adults (1, 2, 6). Moreover, comorbidity is also higher in children and adolescents with OCD, and 80% of the patients may meet the diagnostic criteria for another mental health disorder such as anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, attention deficit disorder, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), or tic disorder because as many as 50% to 60% of youths experience two or more other mental disorders during their lifetime (1, 2, 5-7). Epidemiological studies indicate that the prevalence of OCD in children and adolescents is 2% in Bangladesh, and this finding is in line with studies conducted in different cultures with variations in presentations of symptoms (1, 8). The presentation of OCD symptoms in children and adolescents in Bangladesh is yet to be studied. In this study, we aimed at examining the phenomenology of OCD in children and adolescents in Bangladesh.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Consideration

The researchers were duly concerned about the ethical issues related to the study. Formal ethical clearance to conduct the study was obtained from the ethical review committee of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU). Confidentiality of the information was maintained. Informed written consent was obtained from the participants and their legal guardians after informing them about the nature, purpose, and the procedure of the study. Moreover, the participants could withdraw from the study at any time. Participants did not gain financial benefit from this study. The present study posed a very low risk to the participants, as procedures causing psychological, spiritual, or social harm were not included.

2.2. Design, Participants, and Instruments

This cross- sectional descriptive study was conducted in the child and adolescent psychiatric consultation center in city of Dhaka from January 2014 to December 2014. A total of 106 consecutive patients with OCD aged 5 to 18 years were evaluated. The cases were divided into two groups: children up to 12 years, and adolescents aged 12 to18 years. To assess OCD and comorbidity, the standardized and validated Bangla version of Development and Wellbeing Assessment (DAWABA) was administered (9). Parent DAWBA was used for all the cases, moreover, Self DAWABA was used for the adolescent cases. DAWABA generated ICD-10 DCR (10) diagnoses were assigned for the cases. Only Axis one diagnosis was considered. To assess the symptom pattern of and severity of OCD, children’s Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale (CY-BOCS) (11) was used. This scale has five sections: instruction, obsessions checklists, severity items for obsessions, compulsions check list, and severity items in compulsion. The CY-BOCS comprises 10 severity items, five for the obsessions and five for the compulsions. The severity items assess five aspects pertaining to obsessions and compulsions: frequency, interference, distress, resistance, and control. The 10 severity items are rated on a five- point scale, with none, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme responses for the frequency, interference, and distress items, with always resist and completely yields for the resistance items, and with complete control, much control, moderate control, little control, and no control for the control items. This scale was translated into Bangla through translation/ back-translation and committee translation procedure and was standardized and validated by the researchers. The Bangla version of this scale was used to assess the pattern and severity of OCD among children and adolescents. Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed using a questionnaire designed for the study. Income level was categorized into three bands based on the classification used by the Bangladesh bureau of statistics (2009) (12), which are as follow: low income, ie, less than 10,000 Taka (US$ 140) per month, middle income, ie, 10,000 - 20,000 Taka (US$ 140 - 280) per month, and high income, ie, over 20,000 Taka (US$ 280) per month. Data were managed properly and analyzed with the help of computer software statistical package for social science (SPSS) Version 16.

3. Results

All 106 respondents were students; of them, 41 were children and 65 adolescents, and 69 (65.1%) were boys and 37 (34.9%) girls. Most of the cases were from urban areas (78.3%) and had secondary education (70.8%). Of the cases, 40.6% had a first-degree family history of psychiatric disorder and the highest percentage had anxiety disorders (62.8%), followed by psychotic illness (20.9%) and mood disorder (11.6%).

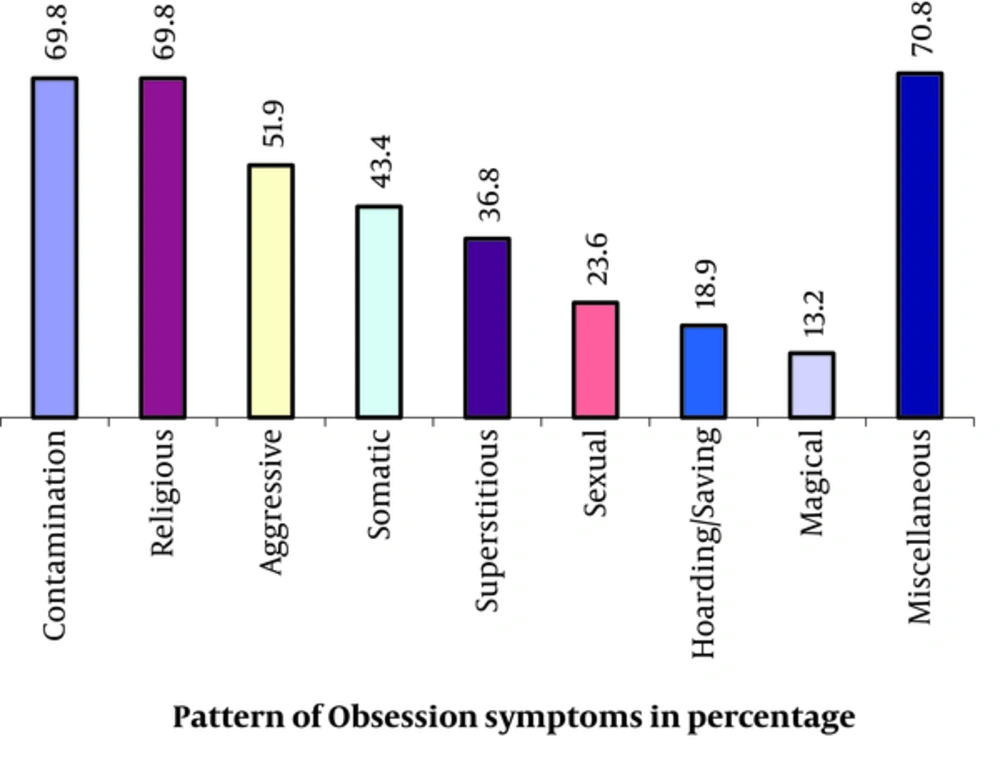

It was found that the highest percentage of patients had miscellaneous obsessions (70.8%), followed by contamination obsession (69.8%) and religious obsession (69.8%) (aggressive obsession (51.9%), somatic obsessions (43.4%), and superstitious obsessions (36.8%) were found among the respondents (Figure 1).

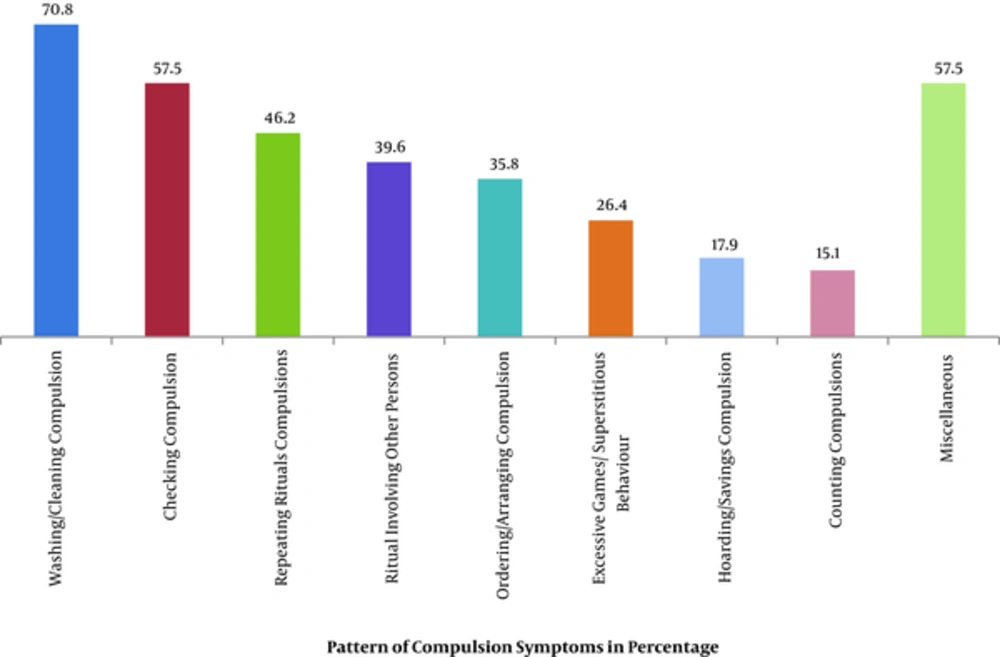

The highest percentage of patients had washing/cleaning compulsion (70.8%), followed by checking compulsion (57.5%) (Figure 2).

Axis one comorbidity was present among 45.3% of the cases with OCD. Most of the patients had hyperkinetic disorder (16.9%), followed by oppositional defiant disorder (13.8%) (Table 1).

| Pattern of Comorbidity | Age, y | Total (n = 106) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 12 (n = 41) | ≥ 12 - 18 (n = 65) | ||

| Separation anxiety disorder | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1 (2.4) | 3 (4.6) | 4 (3.8) |

| Specific phobia | 3 (7.3) | 4 (6.1) | 7 (6.6) |

| Tic disorder | 3 (7.3) | 3 (4.6) | 6 (5.7) |

| Conduct disorder | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.6) | 3 (2.8) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 4 (4.8) | 5 (7.7) | 9 (13.8) |

| Hyperkinetic disorder | 5 (12.1) | 6 (6.1) | 11 (16.9) |

| Major depressive disorder | 0 (0.0) | 6 (15.4) | 6 (5.7) |

| Social phobia | 1 (2.4) | 4 (6.1) | 5 (4.7) |

| Panic disorder | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (1.8) |

| Trichotillomania | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) |

| Comorbidity OCD only | 23 (56.1) | 35 (53.8) | 58 (54.7) |

| Comorbidity | 18 (43.9) | 30 (46.2) | 48 (45.3) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

Table 2 demonstrates the characteristics of obsession according to Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Scale, with the mean score of time spent on obsession and obsession- free interval. Interference from obsessions were higher among the adolescents than children. Moreover, the mean obsession score was significantly higher in adolescents than in children; this difference was statistically significant and was obtained from unpaired student’s t test (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Age, y | Total (n = 106) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 12 (n = 41) | ≥ 12 - 18 (n = 65) | |||

| Time spent on obsession | 0.768 | |||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.7) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Mild | 6 (14.6) | 5 (7.7) | 11 (10.4) | |

| Moderate | 12 (29.3) | 17 (26.2) | 29 (27.4) | |

| Severe | 18 (43.9) | 22 (33.8) | 40 (37.7) | |

| Extreme | 5 (12.2) | 16 (24.6) | 21 (19.8) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | |

| Obsession free interval | 0.184 | |||

| No symptom | 1 (2.4) | 4 (6.2) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Long | 9 (22.0) | 10 (15.4) | 19 (17.9) | |

| Moderately long | 22 (53.7) | 21 (32.3) | 43 (40.6) | |

| Short | 5 (12.2) | 21 (32.3) | 26 (24.5) | |

| Extremely short | 4 (9.8) | 9 (13.8) | 13 (12.3) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | |

| Interference from obsessions | 0.880 | |||

| No symptom | 3 (7.3) | 6 (9.2) | 9 (8.5) | |

| Long | 4 (9.8) | 11 (16.9) | 15 (14.2) | |

| Moderately long | 12 (29.3) | 15 (23.1) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Short | 16 (39.0) | 12 (18.5) | 28 (26.4) | |

| Extremely short | 6 (14.6) | 21 (32.3) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | |

| Distress of obsessions | 0.995 | |||

| No symptom | 5 (12.2) | 7 (10.8) | 12 (11.3) | |

| Long | 4 (9.8) | 12 (18.5) | 16 (15.1) | |

| Moderately long | 7 (17.1) | 9 (13.8) | 16 (15.1) | |

| Short | 14 (34.1) | 13 (20.0) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Extremely short | 11 (26.8) | 24 (36.9) | 35 (33.0) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | |

| Resistance | 0.608 | |||

| Always resists | 3 (7.3) | 5 (7.7) | 8 (7.5) | |

| Capable enough to resist | 1 (2.4) | 2 (3.1) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Average | 4 (9.8) | 4 (6.2) | 8 (7.5) | |

| Nearly failure | 25 (61.0) | 35 (53.8) | 60 (56.6) | |

| Completely yields | 8 (19.5) | 19 (29.2) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | |

| Control over obsessions | 0.498 | |||

| Completely control | 3 (7.3) | 5 (7.7) | 8 (7.5) | |

| Much control | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Moderate control | 5 (12.2) | 5 (7.7) | 10 (9.4) | |

| Little control | 22 (53.7) | 32 (49.2) | 54 (50.9) | |

| No control | 10 (24.4) | 22 (33.8) | 32 (30.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

bP value reached from unpaired student’s t test.

Characteristics of compulsion according to Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Scale are demonstrated in Table 3 and the impact of OCD is presented in Table 4.

| Characteristics | Age, y | Total (n = 106) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 12 (n = 41) | ≥ 12 - 18 (n = 65) | |||

| Time spent on compulsion | 0.877 | |||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.6) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Mild | 4 (9.8) | 7 (10.8) | 11 (10.4) | |

| Moderate | 14 (34.1) | 22 (33.8) | 36 (34.0) | |

| Severe | 18 (43.9) | 17 (26.2) | 35 (33.0) | |

| Extreme | 5 (12.2) | 16 (24.6) | 21 (19.8) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | |

| Compulsion free interval | 0.385 | |||

| No symptom | 1 (2.4) | 6 (9.2) | 7 (6.6) | |

| Long | 8 (19.5) | 6 (9.2) | 14 (13.2) | |

| Moderately long | 20 (48.8) | 27 (41.5) | 47 (44.3) | |

| Short | 11 (26.8) | 18 (27.7) | 29 (27.4) | |

| Extremely short | 1 (2.4) | 8 (12.3) | 9 (8.5) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | |

| Interference from compulsion | 0.782 | |||

| No symptom | 2 (4.9) | 6 (9.2) | 8 (7.5) | |

| Long | 5 (12.2) | 12 (18.5) | 17 (16.0) | |

| Moderately long | 17 (41.5) | 19 (29.2) | 36 (34.0) | |

| Short | 15 (36.6) | 20 (30.8) | 35 (33.0) | |

| Extremely short | 2 (4.9) | 8 (12.3) | 10 (9.4) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | |

| Distress from compulsion | 0.857 | |||

| No symptom | 6 (14.6) | 7 (10.8) | 13 (12.3) | |

| Long | 3 (7.3) | 11 (16.9) | 14 (13.2) | |

| Moderately long | 7 (17.1) | 13 (20.0) | 20 (18.9) | |

| Short | 16 (39.0) | 16 (24.6) | 32 (30.2) | |

| Extremely short | 9 (22.0) | 18 (27.7) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | |

| Resistance | 0.558 | |||

| Always resists | 1 (2.4) | 4 (6.2) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Capable enough to resist | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Average | 6 (14.6) | 13 (20.0) | 19 (17.9) | |

| Nearly failure | 23 (56.1) | 29 (44.6) | 52 (49.1) | |

| Completely yields | 10 (24.4) | 18 (27.7) | 28 (26.4) | |

| Mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | |

| Control over compulsion | 0.883 | |||

| Completely control | 1 (2.4) | 4 (6.2) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Much control | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Moderate control | 10 (24.4) | 13 (20.0) | 23 (21.7) | |

| Little control | 19 (46.3) | 26 (40.0) | 45 (42.5) | |

| No control | 10 (24.4) | 21 (32.3) | 31 (29.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

bP value reached from unpaired student’s t test.

| Characteristics | Age, y | Total (n = 106) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 12 (n = 41) | ≥ 12 - 18 (n = 65) | |||

| Insight into O-C symptom | 0.001 | |||

| Excellent | 4 (9.8) | 23 (35.4) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Good | 10 (24.4) | 26 (40.0) | 36 (34.0) | |

| Average | 13 (31.7) | 11 (16.9) | 24 (22.6) | |

| Little | 11 (26.8) | 2 (3.1) | 13 (12.3) | |

| Absent | 3 (7.3) | 3 (4.6) | 6 (5.7) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | |

| Avoidance | 0.227 | |||

| None | 4 (9.8) | 11 (16.9) | 15 (14.2) | |

| Mild | 5 (12.2) | 4 (6.2) | 9 (8.5) | |

| Moderate | 21 (51.2) | 18 (27.7) | 39 (36.8) | |

| Severe | 9 (22.0) | 19 (29.2) | 28 (26.4) | |

| Extreme | 2 (4.9) | 13 (20.0) | 15 (14.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | |

| Indecisiveness | 0.290 | |||

| None | 5 (12.2) | 8 (12.3) | 13 (12.3) | |

| Mild | 2 (4.9) | 2 (3.1) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Moderate | 21 (51.2) | 27 (41.5) | 48 (45.3) | |

| Severe | 10 (24.4) | 16 (24.6) | 26 (24.5) | |

| Extreme | 3 (7.3) | 12 (18.5) | 15 (14.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | |

| Pathologic responsibility | 0.406 | |||

| None | 6 (14.6) | 9 (13.8) | 15 (14.2) | |

| Mild | 1 (2.4) | 2 (3.1) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Moderate | 10 (24.4) | 10 (15.4) | 20 (18.9) | |

| Severe | 15 (36.6) | 22 (33.8) | 37 (34.9) | |

| Extreme | 9 (22.0) | 22 (33.8) | 31 (29.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | |

| Slowness | 0.515 | |||

| None | 1 (2.4) | 6 (9.2) | 7 (6.6) | |

| Mild | 3 (7.3) | 2 (3.1) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Moderate | 11 (26.8) | 14 (21.5) | 25 (23.6) | |

| Severe | 19 (46.3) | 18 (27.7) | 37 (34.9) | |

| Extreme | 7 (17.1) | 25 (38.5) | 32 (30.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | |

| Pathologic doubting | 0.643 | |||

| None | 4 (9.8) | 6 (9.2) | 10 (9.4) | |

| Mild | 3 (7.3) | 4 (6.2) | 7 (6.6) | |

| Moderate | 15 (36.6) | 25 (38.5) | 40 (37.7) | |

| Severe | 16 (39.0) | 20 (30.8) | 36 (34.0) | |

| Extreme | 3 (7.3) | 10 (15.4) | 13 (12.3) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | |

| Global severity | 0.560 | |||

| Global severity None | 1 (2.4) | 3 (4.6) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Mild | 3 (7.3) | 2 (3.1) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Moderate | 8 (19.5) | 14 (21.5) | 22 (20.8) | |

| Severe | 20 (48.8) | 24 (36.9) | 44 (41.5) | |

| Extreme | 9 (22.0) | 22 (33.8) | 31 (29.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | |

| Global improvement | 0.543 | |||

| None | 9 (22.0) | 18 (27.7) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Mild | 21 (51.2) | 21 (32.3) | 42 (39.6) | |

| Moderate | 5 (12.2) | 13 (20.0) | 18 (17.0) | |

| Severe | 4 (9.8) | 9 (13.8) | 13 (12.3) | |

| Extreme | 2 (4.9) | 4 (6.2) | 6 (5.7) | |

| Mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | |

| Reliability | 0.027 | |||

| Excellent | 9 (22.0) | 26 (40.0) | 35 (33.0) | |

| Good | 18 (43.9) | 28 (43.1) | 46 (43.4) | |

| Fair | 14 (34.1) | 10 (15.4) | 24 (22.6) | |

| Poor | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

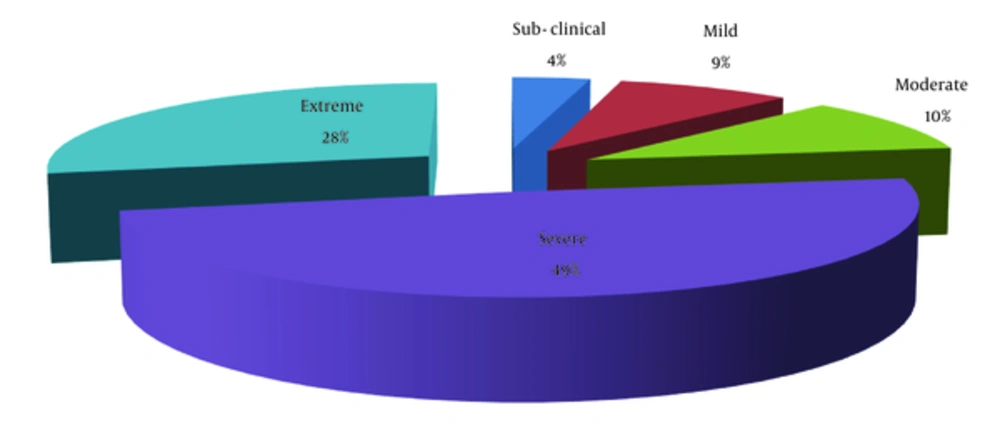

Percent distribution of severity of OCD among the respondents according to CY-BOCS revealed that about half of the patients had severe OCD (49%), 28% extreme OCD, 10% moderate OCD, and only 9% had mild OCD (Figure 3).

Table 5 demonstrates the relationship between morbidity and religious practice and the cultural belief of the patient and the family. The results of the analysis revealed that OCD with comorbidity was related to the religious practice of the patients, which was statistically significant (Table 5).

| Characteristics | Total (n = 106) | Age, y | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 12 (n = 41) | ≥ 12 - 18 (n = 65) | |||

| Belief of the parent regarding child’s disease | NS | |||

| Physical illness | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Mental illness | 95 (89.6) | 37 (90.2) | 58 (89.2) | |

| Influence of something evil | 2 (1.9) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Do not know | 6 (5.7) | 2 (4.8) | 4 (6.2) | |

| Religious practice by patient | 0.001 | |||

| Extreme | 23 (21.7) | 2 (4.9) | 21 (32.3) | |

| Moderate | 55 (51.9) | 21 (51.2) | 34 (52.3) | |

| None | 28 (26.4) | 18 (43.9) | 10 (15.4) | |

| Religious practice by father | NS | |||

| Extreme | 32 (30.2) | 9 (21.9) | 23 (35.4) | |

| Moderate | 66 (62.3) | 29 (70.7) | 37 (56.9) | |

| None | 8 (7.6) | 3 (7.4) | 5 (7.7) | |

| Religious practice by mother | NS | |||

| Extreme | 37 (34.9) | 9 (21.9) | 28 (43.1) | |

| Moderate | 63 (59.4) | 29 (70.7) | 34 (52.3) | |

| None | 6 (5.7) | 3 (7.4) | 3 (4.6) | |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

bP value reached from chi square test.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the phenomenology of OCD in children and adolescents in Bangladesh and found that 40.6% of patients had a first- degree family history of psychiatric illness. The overall pattern of family history indicated that most patients had anxiety disorder (62%), followed by psychotic illness, and mood disorder. This result suggests a biological basis for OCD and genetic studies that find higher concordance rates of OCD in first- degree family members and twins than in general population (Table 1) (1-4, 11). A recent published study by Chowdhury et al. found similar results in a hospital setting, indicating that 45% of patients had a family history of mental disorders with deviation to OCD (1). According to CY-BOCS, the pattern indicates that most of the patients had miscellaneous obsessions (70.8%), which mainly included pathological doubt, followed by contamination obsession (69.8%), and religious obsessions (69.8%). These findings are consistent with those of other similar representative studies with variations in percentages of the symptoms; for example, in the study of Chowdhury et al. miscellaneous obsession was lower than 56.7% (Figure 1) (1, 12, 13). The variation could be explained by differences in the study setting, as one study was conducted in a hospital setting and another was done in a consultation center. The CY-BOCS pattern of compulsion indicates that most patients had washing/cleaning compulsion, followed by checking compulsion, and miscellaneous obsession; and the findings are in agreement with those of other studies with variations in percentage (Figure 2) (12, 13). The present study revealed that comorbidity was present among 45.3% of children and adolescents with OCD, which is in between the widely variable range of other studies (Table 1) (1, 2, 4, 6, 11, 14, 15). The pattern of comorbidity also indicated that most patients had hyperkinetic disorder, followed by oppositional defiant disorder, specific phobia, and major depressive disorder comparable to other findings except for the absence of alcohol and drug related disorders and eating disorder, which can be explained by Bangladeshi sociocultural background (1, 16). Moreover, variations in comorbidity that were found in the study of Chowdhury et al. can also be explained by different study settings. Comorbidity pattern also showed two specific patterns for children and adolescent groups. The proportions of major depressive disorder (15.1%), followed by social phobia (6.1%) and hyperkinetic disorder (6.1%) were higher among the adolescents, whereas hyperkinetic disorder (12.1%), tic disorder (7.3%), and specific phobia (7.3%) were higher among children (Table 1). This finding is somewhat consistent with other study findings and the differences could be explained by study setting (1, 2, 4, 6, 11, 16). Considering the caregivers’ perception about the child’s disease, 89.6% believed that it was mental illness, which indicates good awareness among parents of OCD patients. However, we should also keep in mind that most of the parents had good educational and economic background, and the results can be compared with those of the study by Chowdhury et al. which revealed that 88.3% of the participants regarded OCD as a mental illness (Table 5) (1). The present study revealed a statistically significant relationship between OCD and the religious practice of the patients (Table 5); this can be explained by overall religious practices and beliefs of Bangladeshi people. Moreover, similar results were found in another study that assessed the relationship between OCD symptoms and religious practice (1, 8).

In conclusion, OCD is a poorly studied disorder of children and adolescents in Bangladesh.Miscellaneous and contamination obsessions are prominent as obsessions, whereas checking and miscellaneous obsessions are prominent as compulsions in Bangladesh. Conducting further large scale multi-centered studies would help generalize the study results. Moreover, taking the necessary steps based on the results would reduce the distress and sufferings of children and adolescents.