1. Background

One of the most important factors in sustaining marriage is couples’ commitment. The factors, which define the psychology of close relationships include emotional involvement, dividing thoughts and feelings, and interpersonal dependence or commitment. These factors describe what close relationships are and why individuals form such relationships, and how they develop them. The first factor is emotional involvement, which includes romantic emotions, and warmth and loyalty towards the partner. The second factor involves sharing individual’s emotions and experiences and the third factor is dependence and commitment between two individuals that tie their prosperity together (1). From Amato’s point of view, marital commitment is defined as the value that couples place on for their marital relationships and how motivated they are to sustain their marriage (2). Commitment means an individual loves their spouse, i.e. they are loyal to them and avoid any form of relationship with others’ spouse (3). Commitment is a referral framework of values and beliefs that may be self-made or prescribed by others (4). Commitment in marriage is defined as the way couples understand the type of relationship in the past and the length of relationship, selecting the behaviors for sustaining marital life, the degree and vastness of a good relationship and an interest in remaining in such a relationship for a long time, and being encouraged to remain in the relationship (5). Marital commitment is divided to two types: Commitment to spouse and institutional commitment. Commitment to spouse results in maintaining a high level of love and satisfaction in life, while in institutional commitment, an individual pretends to love their spouse although they are not interested in them and they have some other reasons for their commitment to marriage (6). Without commitment there is no direction and goal in life. If any acquaintance with a focus on marriage does not reach a particular commitment, they will be a failed acquaintance. Commitment is the most powerful and adaptable predictor for a relationship’s satisfaction, particularly for the longest relationships (7). McDonald believes that marriage commitment includes marital commitment and interpersonal commitment. Marital commitment is defined as a person’s interest in marrying a particular person and being committed to them and it is often treated as a specific kind of commitment and involves legal, social, and interpersonal complications (8). Strachman and Gable identified and proposed two types of commitment in marital relationships, including commitment to tendency and commitment to avoidance. Commitment to tendency shows a person’s interest in maintaining a marital relationship, while commitment to avoidance implies an individual’s tendency to avoid ending a marital relationship. In simple words, tendency commitment is related to merits and rewards of marital life in the present and future. However, avoidance commitment involves the negative consequences of divorce and costs and subsequent outcomes of separation (9). Adams and Jone conducted a general investigation of marital commitment and specified three dimensions, including element of attraction, inhibitive dimension, and ethical aspect. In order to find further evidence to support this three-factor structure, they regarded marital commitment as a kind of structural commitment, which is sacred. They also realized that commitment criteria change according to a reference or goal (10). Rusbult considers commitment in a relationship investment model as a powerful predictor in sustaining many romantic relationships (for example, marital relationship, homosexual relationship, and friendship). The investment model was first introduced by Rusbult in 1980. This model focuses on the process of marital commitment as much as it focuses on the conditions of a relationship’s deterioration. The supporters of this model believe that commitment is an important predicting factor in betrayal. Commitment decreases the temptation for betrayal and provides resources for individuals to enable them to change their focus from seeking long-term pleasure. Therefore, people with a high level of commitment, are more likely to avoid marital betrayal, while people with a low level of commitment may become involved in extramarital relationships. According to Rusbult’s investment model, commitment in marital life is affected by marital satisfaction, the quality of alternatives and investments (11).

The investment model in commitment processes has its roots in mutual dependence and has obtained its pattern from zeitgeist in 1960s and 1970s, which is in search of understanding the reason behind an apparently illogical sustenance of such relationships in social behavior. The investment model originally belonged to the field of social psychology, and was beyond a mere focus on positive affection in predicting the sustenance of an interpersonal relationship.

The investment model (1983) provides a useful framework to predict commitment to someone or something and understand the background for commitment reasons. The main hypothesis in the investment model is that the sustenance of relationships is not only due to the positive traits of partners for each other (mutual satisfaction), yet for partners’ connections and relationships with each other (investment) and lack of a better choice beyond the relationship with the current partner (lack of alternative). All these factors are crucial in understanding commitment. According to Rusbult’s investment model, in marital life, commitment is influenced by marital satisfaction, the quality of alternatives and investments (11).

A) Marital satisfaction: Satisfaction is a kind of mental evaluation for relative rewards and punishments, which are experienced by an individual in a relationship. They clarify that commitment is reinforced by satisfaction in the relationship. In order to determine the level of satisfaction, people evaluate the costs and rewards in their relationship. The potential benefits and rewards are compared with the individual’s expectations in a relationship. These personal standards are known as assessment criteria. This level of satisfaction is the function of evaluating the level and results of the current relationship. When the obtained results exceed the criterion level, an individual is satisfied with their level, yet when the obtained results are lower than the internal standards, dissatisfaction occurs (11).

Research in western countries has revealed that illegitimate relationships take more emotional energy among women and women, who betray are more likely to be dissatisfied with their marital relationship (12).

B) The quality of alternatives: The second effective factor in commitment is traits of alternatives, which refer to an individual’s mental assessment of rewards and costs, which are obtained by an individual out of their current relationship, such as spending time with friends, family or spending time in solitude. Basically, the traits of alternatives are related to potential feelings of happiness in an extramarital relationship. Consequently, having attractive alternatives is a potential to reduce marital commitment (12).

C) Investments: The third form of commitment includes relationship investment. Investments are obtained tangible or real resources, which intensively reduce the probability of a relationship’s deterioration. Some examples for relationship investment include spending time, affectionate dependence, mutual friends and materialistic possessions. According to the investment model, all these valuable investments have a share in reinforcing commitment (11).

In a study conducted by Gao (2000), titled “intimacy, passion, and commitment in romantic relationships” in China and America, the triangular theory of love was investigated in these countries. The data was collected from 90 couples in China and 77 couples in America. Data analysis was done using multi-variable variance and score summation and the results showed that commitment, love, and intimacy could noticeably improve a romantic relationship. In addition, passion is significantly higher among American couples in comparison to Chinese couples. However, commitment and intimacy had no difference in these cultures. On the other hand, Riviz (2006), in a study titled “marital commitment”, arrived at this conclusion that in a marital relationship, there are some ups and downs, and couples are required to work to find a solution in order to maintain a committed relationship. He believed that the key points to build a successful marriage are commitment, loyalty, positive thoughts, proper relationship, kindness, understanding, respect, and common goals. Galna and Stanley (2006) also investigated interactions before marriage and commitment among married people. They investigated the level of individual commitment in 197 married individuals, according to interactions before marriage, longitudinally. The results revealed that men, who had interactions with their wives and cohabited before marriage, were less committed. In Iran, Taba’e Emami, in a study titled “determining and investigation of the relationship between central and peripheral traits of love and commitment among young adults in Isfahan, reached the conclusion that the average scores of grading central traits of love and commitment were significantly related to the peripheral traits of love and commitment. The average grading of males and females was compared by making use of variance analysis. Although there were some differences between central traits of love and commitment among men and women, no significant difference was observed between them in terms of peripheral traits of love and commitment. Another study conducted by Shahsiah (2009), titled “the investigation of the relationship between sexual satisfaction and marital commitment”, revealed that there is a significant relationship between marital commitment and sexual satisfaction and there is a relationship between marriage length and marital commitment and sexual satisfaction, and the shorter the length of marriage, the more the sexual satisfaction. Najarpourian (2009) in a study titled “the effect of teaching commitment before marriage on improving commitment traits among female students of Fasa Azad University”, which was conducted randomly on 30 female dormitory students, revealed that teaching commitment improves commitment traits among students and the post-test scores of the experimental group was significantly higher than the control group. This research suggests that in premarital educational programs, the importance and role of commitment and its traits should be added in order to make couples more responsible for starting their marital life.

2. Objectives

Given the fact that there are no questionnaires suitable for the Iranian population in the field of marital commitment, and considering the cultural differences between Iran and other societies, it was required to localize a questionnaire in this field, therefore, the aim of this research was to investigate the psychometric properties of Rusbult’s relationship investment scale based on the analysis of the main components via varimax rotation to obtain a precise instrument to evaluate the quality of relationship for Iranian population samples.

3. Methods

In order to investigate the factor structure of the questionnaire in this study, exploratory factor analysis was utilized and by making use of Cronbach’s alpha, the questionnaire’s internal consistency was measured.

The statistical population of this study consisted of all married students at Payame Noor University in during academic years 2017 to 2018, including 1416 students, out of which 302 students were selected through convenience sampling.

3.1. Instruments

3.1.1. Rusbult’s Relationship Investment Scale (1998)

Rusbult, Martz and Agnew (1998) re-evaluated the former scales, which were used to evaluate the relationship status in the investment model (13). This scale is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring the four main structures of the investment model including: (1) Commitment, (2) satisfaction, (3) alternatives choices, and (4) investment. The investment model determines the amount of commitment for remaining in a relationship, which is dependent on the level of satisfaction, investment rate, and the quality of alternative choices (14). Each of these four subscales either includes a general item or a one-dimensional item, in which one-dimensional items provide a background for answering general items, as it is assumed that one-dimensional items enhance the validity and reliability of the instrument. In the commitment subscale, only general items were used.

All the items included sentences, and respondents marked their level of agreement. For one-dimensional items, four-degree Likert scale was used, where one represented “disagreement” and four represented “absolute agreement” yet in general items, a nine-degree Likert scale was used, in which eight represented “absolute agreement” and zero represented “disagreement”.

- “Satisfaction” subscale included five one-dimensional and five general items. The items involve themes, such as intimacy, accompanying, sex, security, and the rate of emotional involvement in a relationship.

- “Quality of alternatives” subscale included 10 items and its goal was to evaluate requirements in an alternative relationship, such as friends, family or other beloved ones in a gradable way.

- The “rate of investment” subscale included 10 items that measured the amount of self-esteem and sharing memories, identity, and thoughts.

- “Commitment” subscale included seven general scales.

Grading this scale was done by summation of all scores in each subscale and a high score in each subscale (the summation of all scores in that subscale) showed the prominence of that trait in that individual.

This instrument had a high reliability. Rusbult et al. in 1998 reported that the Cronbach’s alpha for the satisfaction subscale was between 0.92 and 0.95, for the quality of alternatives it was between 0.82 and 0.88, for the amount of investment it was between 0.82 and 0.85, and for commitment level it was between 0.91 and 0.95. Furthermore, its validity was confirmed by factor analysis. The effect of mutual factors was more than 0.40 (15).

In order to ask the subjects to fill out the questionnaires, at first, an official permission was obtained and the subjects were provided with explanations concerning how to answer the questions honestly, and then they were asked to answer the questionnaire.

4. Results

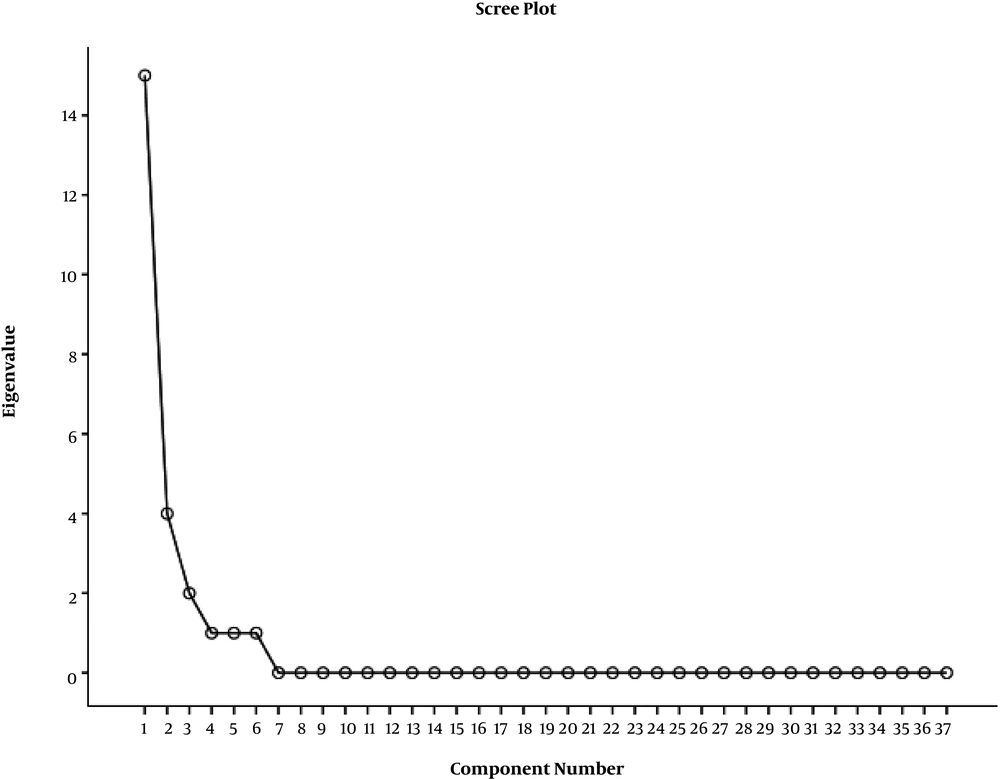

At first, in order to check the appropriateness of the collected data, Bartlett’s test of sphericity and Kaiser Meyer Olkin test were used in which the amount of KMO for questions’ correlation matrix was 0.92, which showed the data was suitable for the main analysis and the amount of Bartlett’s test for the content of the 9217.383 questionnaire was significant at the level of P < 0.000, which confirmed the presence of sufficient correlation between variables. After making sure of the above indices, using factor analysis through the main components, the questionnaire items were analyzed by factor analysis, which resulted in the best content, indicate by the Scree Figure 1 and the percentage of four-factor matrix.

After applying varimax rotation to the questionnaire factors, the content of each factor was specified, according to each question’s factor loading, Table 1. According to Table 2 (variance of factors), the specific amounts were determined in four factors, which justified 62.35% of Rusbult’s investment relationship scale variance so that the first factor (satisfaction) had 15 items and its participation percentage was 15.05%, the items of the second factor (alternative choices) included 10 items and had a participation percentage of 4.33%. The third factor (investment) with seven questions, had participation percentage of 2.04%, and the fourth factor (commitment) with five questions had a rate of 1.63%, which had a significant role to justify Rusbult’s relationship investment scale variance.

| Question | Fourth Factor | Question | First Factor | Question | Second Factor | Question | Third Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0.784 | 31 | 0.75 | 19 | 0.80 | 15 | 0.90 |

| 5 | 0.780 | 36 | 0.71 | 20 | 0.76 | 12 | 0.87 |

| 1 | 0.774 | 32 | 0.70 | 17 | 0.75 | 14 | 0.81 |

| 9 | 0.773 | 37 | 0.69 | 16 | 0.68 | 11 | 0.80 |

| 7 | 0.757 | 36 | 0.66 | 34 | 0.63 | 13 | 0.74 |

| 6 | 0.751 | 35 | 0.674 | 18 | 0.59 | ||

| 10 | 0.745 | 30 | 0.644 | 33 | 0.36 | ||

| 3 | 0.744 | 28 | 0.63 | ||||

| 4 | 0.736 | 29 | 0.55 | ||||

| 2 | 0.663 | 27 | 0.52 | ||||

| 24 | 0.619 | ||||||

| 21 | 0.551 | ||||||

| 22 | 0.534 | ||||||

| 25 | 0.525 | ||||||

| 23 | 0.421 |

| Factors | First Factor | Second Factor | Third Factor | Fourth Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance | 15.05 | 4.33 | 2.04 | 1.63 |

| Total variance | 62.35 |

In addition, to evaluate the reliability of the scale, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used; Table 3 represents Cronbach’s alpha coefficient results for each of the factors.

According to Table 3, all the factors had suitable reliability

| Factors | Alpha Magnitude | The Number of Questions | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| First factor | 0.94 | 15 | 59.76 ± 15.52 |

| Second factor | 0.92 | 10 | 60.45 ± 16.53 |

| Third factor | 0.83 | 7 | 18.04 ± 35.76 |

| Fourth factor | 0.91 | 5 | 8.46 ± 4.15 |

Considering the data in Table 4, the cut point score for the four factors are seen above; cut point score is a score, which can be used to interpret the scores obtained from the questionnaire.

| Factors | T Cut Point Score |

|---|---|

| First factor | 90.04 |

| Second factor | 93.51 |

| Third factor | 89.56 |

| Fourth factor | 16.76 |

5. Discussion

This study aimed at the validation of Rusbult’s relationship investment scale, which is an instrument designed based on Rusbult’s relationship investment model. According to the investment model, level of satisfaction, the rate of investment, and the quality of alternative choices determine the amount of commitment for remaining in a relationship. When couples satisfy their expectations and the positive aspects of their relationship outweigh the negative ones, their satisfaction level rises, and as a result, they will remain committed. If couples invest more in togetherness, mutual emotions, feelings and common interests, and the quality of the relationship with another person is weak, consequently, it is more likely to remain committed to their relationship. Studies show that commitment is the best and most powerful predictor for a relationship’s sustainability and it plays a role as a mediator between satisfaction, the quality of a new relationship (a new person), and investment in marital life (16).

In the validation stage, through the analysis of factors, it was revealed that Rusbult’s investment scale has an acceptable level of validity in psychometry. It can be potentially used to explain a level of commitment to relationship. In addition, the results obtained from Cronbach’s alpha, demonstrates the high internal consistency of this test. At the end, it is suggested that in order to generalize the findings, it would be better to ask the other communities of people (in terms of age, education, and social class) to complete this questionnaire.