1. Context

Campylobacter species are microaerophilic and gram-negative rods, non-fermenting, Oxidase-positive, and motile and spiral-shaped with a single polar flagellum. They can grow quite slowly (72 h - 96h) at 37°C or 42°C in primary isolation (1-3). However, Campylobacter is a common bacterium in animals, which is the main cause of Campylobacteriosis in humans. It is well documented that meat consumption may be the main source of infection in the most sporadic cases of Campylobacter enteritis. Consequently, Campylobacter coli (C. coli) and Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) are the most common specimens isolated from human clinical specimens (3-6). Globally, 20% - 35% of human diarrheas can be attributed to C. jejuni (7). Illnesses caused by Campylobacter are usually self-limiting, hence, no treatment is required in most cases, except for immunocompromised patients that antibiotic therapy may be necessary. This therapeutic option can be a major reason for antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter (8). Nowadays, several methods are available to identify Campylobacter spp. such as biochemical, molecular, and serological reaction methods (9-12). Indiscriminate application of antimicrobials in animal products and occurrence of antimicrobial-resistant foodborne Campylobacter is a serious issue in both veterinary and human medicines, which is mentioned as a public health problem by several studies (13-15).

The current review study intended to investigate the prevalence and antibiotic resistance of C. coli and C. jejuni in animal, food products, and human clinical specimens during 2004 - 2017 in Iran.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Search Strategy

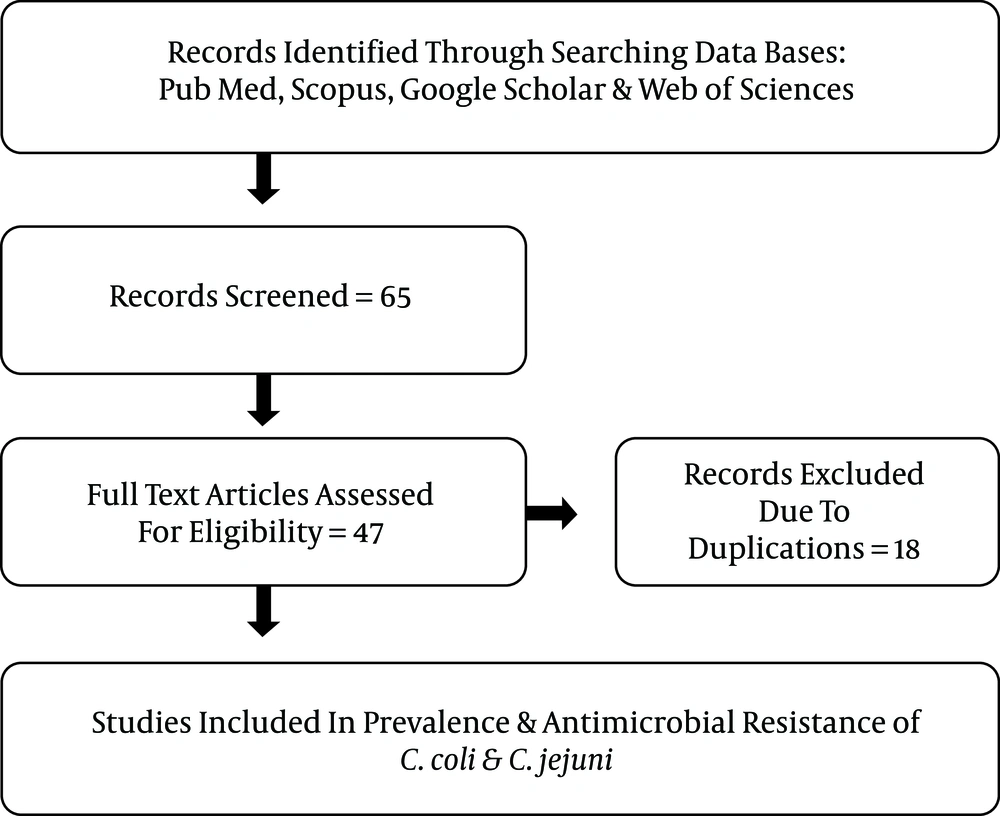

We systematically searched biomedical databases (PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of sciences) to identify relevant studies from 2004 to 2017, either in English or in Persian. The search was performed using various combinations of the following keywords: “Campylobacter spp. AND Iran”, “Campylobacter spp. AND human clinical samples AND Iran”, “antimicrobial resistance AND Campylobacter spp. AND Iran”, “C. jejuni OR C. coli AND animals AND Iran”, “C. jejuni OR C. coli AND food products AND Iran”. In addition, to increase the comprehensiveness of the search, additional studies were sought from the reference lists of included studies. To explain the spread and development of antibiotic resistance, we reviewed the literature published based on prevalence and antibiotic-resistant of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni. Out of 65 identified articles, 47 were published from 2004 to 2017. The quality assessment was performed according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist. It worth noting that we tried to find studies performed in various regions of the country to increase the comprehensiveness of the findings.

2.2. The Inclusion Criteria

1) Data on prevalence studies were selected and categorized based on their sample, the frequency of animal and food products separated by the region, sample size, and sample collection according to the publication year (from 2004 to 2017).

2) Clinical specimens, including blood, stool, and acute diarrhea, were collected from hospitalized patients in five studies on animal sources and food products, which typically were collected from a slaughterhouse, stockyard, and stores.

3) Research studies that were employed different methods such as bacteriological culture, biochemical tests, PCR Methods (RT-PCR, Multiplex PCR, Nested PCR, and PCR-RFLP), PFGE genotyping, and blood culture were included.

4) Studies on antimicrobial susceptibility tests (AST). In all of the studies, AST was performed by the disk diffusion (Kirby-Bauer) method using the Mueller Hinton agar. These data are provided in Tables 1-3.

| Authors, Publication Year | Performed Year | Region | Human Sample | Sample Size, No | Positive sample, No. (%) | Age Group | C. coli, % | C. jejuni, % | Detection Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feizabadi et al., 2007 | 2004 - 2005 | Tehran | Diarrheic | 500 | 40 (8) | ≤ 1 - 12 | 14.2 | 85.8 | Biochemical, PCR | (16) |

| Hassanzadeha et al., 2007 | 2007 | Shiraz | Acute diarrhea | 114 | 40 (35) | 2–58 | - | 9.6 | Culture, biochemical | (17) |

| Ghorbanalizadgan et al., 2014 | 2012 - 2013 | Tehran | Stool specimens | 200 | 12 (6) | ≤ 5 | 1.5 | 4.5 | Biochemical, PCR | (18) |

| Mobaien et al., 2016 | 2013 - 2014 | Zanjan | Stool specimens | 864 | 40 (4.6) | adult | - | 4.6 | RT-PCR | (19) |

| Ranjbar et al., 2017 | 2016 | East Azerbaijan | Stool samples | 1020 | 79 (7.7) | 18 - 70 | 7.6 | 24.7 | Culture, PCR | (20) |

Prevalence Studies of Campylobacter Infections Based on Clinical Human Specimens

| Authors, Publication Year | Performed Year | Region | Animal and Food Sample | Type of Sample | Sample Size, No | Positive Sample, No. (%) | From Positive Sample | Method | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. coli% | C. jejuni% | |||||||||

| Bakhshi et al., 2016 | 2004 - 2005 | Tehran | Food product | Food product, Patients with Diarrhea | 45 | 30 (66) | 66.6 | 33.3 | PCR, biochemical tests | (21) |

| Dallal et al., 2011 | 2006 - 2007 | Tehran | Animal product | Chicken, beef | 379 | 109 (28) | 24 | 76 | Culture, biochemical tests | (22) |

| Rahimi et al., 2010 | 2007 | Isfahan | Animal product | Commercial poultry | 348 | 216 (62) | 19 | 81 | PCR method | (23) |

| Rahimi et al., 2008 | 2006 - 2008 | Isfahan | Animal product | Poultry meat, quail, ostrich | 800 | 377 (47) | 23.6 | 76.4 | Culture | (24) |

| Kazemeini et al., 2011 | 2008 - 2009 | Isfahan | Food product | Bovine milk | 120 | 3 (2.5) | No detect | 100 | Culture, biochemical tests | (25) |

| Ansari-Lari et al., 2011 | 2009 | Shiraz | Animal product | Broiler flocks | 100 | 76 (76) | 56.5 | 43.5 | Multiplex PCR | (26) |

| Abdi-Hachesoo et al., 2014 | 2009 | Shiraz | Animal product | Broiler flocks | 100 | 83 (83) | 48.2 | 51.8 | Multiplex PCR | (27) |

| Jamali et al., 2015 | 2008 - 2010 | Tehran | Animal product | Duck, goose intestinal content | 471 | 161 (34) | 14.3 | 85.7 | Culture | (28) |

| Rahimi et al., 2013 | 2009 - 2010 | Chaharmahalva Bakhtiari, Khuzestan | Animal product | Raw meat, Camel, Buffalo | 379 | 31 (8) | 22.6 | 77.4 | Culture, Nested PCR | (29) |

| Rahimi et al., 2011 | 2009 - 2010 | Shahrekord | Animal product | Chicken, turkey, quail, ostrich | 494 | 187 (37) | 8 | 92 | Cultural, PCR | (30) |

| Shahrokhabad et al., 2011 | 2010 | Rafsanjan | Animal product | Broilers slaughter | 100 | 31 (31) | 38.71 | 61.29 | Culture | (31) |

| Mirzaie et al., 2011 | 2010 | Tehran | Animal product | Turkeys, quails | 125 | 52 (41) | 80.5 | 19.5 | Culture, biochemical tests | (32) |

| Rahimi et al., 2011 | 2011 | Shahrekord | Animal product | Raw duck, goose meat | 169 | 169 (100) | 88.5 | 11.5 | Cultural& PCR | (33) |

| Rahimi et al., 2013 | 2011 | Sharekord | Animal product | Chicken, quail, sheep turkey, goat, Ostrich | 214 | 213 (99.5) | 9.3 | 90.7 | Culture, biochemical, PCR | (34) |

| Hosseinzadeh et al., 2015 | 2011 | Uremia | Animal product | Chicken wings | 96 | 40 (41.6) | No detect | No detect | Cultural, PCR | (35) |

| Dabiri et al., 2014 | 2011 - 2012 | Tehran | Animal product | Chicken, beef meat | 450 | 121 (26.8) | 23.2 | 76.8 | Culture | (36) |

| Zendehbad et al., 2013 | 2012 | Khorasan | Animal product | poultry meat, partridge, turkey | 300 | 149 (49.6) | 19.2 | 80.8 | Cultural, PCR assay | (37) |

| Raissy et al., 2014 | 2012 | Azerbaijan | Animal product | Crayfish | 97 | 2 (2) | No detect | No detect | Cultural, PCR | (38) |

| Khoshbakht et al., 2015 | 2012 | Shiraz | Animal product | Broiler feces | 90 | 90 (100) | 53.4 | 46.6 | Multiplex PCR, PCR RFLP | (39) |

| Zendehbad et al., 2015 | 2013 | Mashhad | Animal product | Broiler meat | 360 | 227 (63) | 11.9 | 88.1 | Cultural, PCR | (40) |

| Khoshbakht et al., 2016 | 2011-2013 | Shiraz | Animal product | Fecal samples of slaughtered cattle, sheep | 302 | 270 (89) | No detect | No detect | Culture, multiplex PCR | (41) |

| Ehsannejad et al., 2015 | 2014 | Tehran | Animal product | Pet birds | 660 | 20 (3) | 20 | 80 | Cultural, multiplex-PCR | (42) |

| Haghi et al., 2015 | 2014 | Zanjan | Food product | Bovine and ovine raw milk | 60 | 0 (0) | No detect | No detect | PCR | (43) |

| Jonaidi-Jafari et al., 2016 | 2014-2015 | Isfahan | Food product | Avian eggs | 440 | 34 (7.7) | 17.7 | 82.3 | Culture, PCR | (44) |

| Rahimi et al., 2017 | 2017 | Isfahan | Animal product | livestock feces from sheep, goat, cattle | 400 | 28 (7) | 21.5 | 78.5 | Culture, PCR | (45) |

Prevalence Studies of Campylobacter spp. Based on Animal Sources and Food Products

| Antimicrobial Agent | Studies Year (2004 - 2017), Number of Study | Min-Max resistant reported articles for C. coli, % | Min-Max Resistant Reported Articles for C. jejuni, % | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gentamicin | (2004 - 2013, 2017), (14) | 0 - 8.3 | 0 - 10 | (16, 18, 22, 28, 29, 31-34, 36, 37, 41, 44, 45) |

| Neomycin | (2004 - 2013, 2015), (8) | 0 - 9 | 0 - 8.5 | (16, 22, 28, 32, 36, 37, 41, 44) |

| Chloramphenicol | (2004 - 2013, 2017), (15) | 0 - 8.4 | 1.4 - 8.3 | (16, 22, 28, 29, 31-34, 36, 37, 40, 41, 45, 46) |

| Erythromycin | (2004 - 2013, 2017), (14) | 0 - 40 | 0.8 - 7.1 | (16, 22, 28, 31-34, 36, 37, 44, 46) |

| Streptomycin | (2004 - 2013, 2017), (12) | 4.3 - 89.7 | 1.7 - 8.6 | (16, 22, 28, 29, 31, 33, 34, 36, 37, 44-46) |

| Amoxicillin | (2006 - 2012, 2015 - 2017), (12) | 3.7-79.5 | 1.7 - 31.9 | (22, 28, 29, 31, 33, 34, 36, 37, 40, 44-46) |

| Ampicillin | (2004 - 2013, 2015 - 2017), (15) | 4.3 -8 2 | 6.5 - 50 | (16, 22, 28, 29, 31-34, 36, 37, 41, 44-46) |

| Colistin | (2004 - 2012, 2015), (7) | 0 - 35 | 0 - 34.2 | (16, 22, 28, 36, 37, 41, 44) |

| Tetracycline | (2004 - 2013, 2017), (14) | 18.2 - 94 | 22.2 - 80 | (16, 22, 28, 29, 31-34, 36, 37, 41, 44-46) |

| Nalidixic acid | (2004 - 2013, 2017), (14) | 14.3 - 100 | 13 - 75.8 | (16, 22, 28, 29, 31-34, 36, 37, 41, 44-46) |

| Ciprofloxacin | (2004 - 2013, 2017), (15) | 30.3 - 100 | 29 - 87.7 | (16, 22, 28, 29, 31-34, 36, 37, 40, 41, 44-46) |

Characteristic of Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern of C. coli and C. jejuni in Studies Performed in Iran

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

1) Studies that did not investigate the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance on C. coli and C. jejuni.

2) Studies about other Campylobacter spp. and case reports.

3) Duplicate documents.

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using EXCEL 2019, including numerical and averaging calculations.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence Rates for Different Samples

Data of the spread of the investigated agent were available for the period of 2004 to 2017 (13 years). In total 9933 specimens from human tissues, as well as animal and food products, were investigated (Tables 1 and 2). The prevalent rate of C. coli and C. jejuni in several regions are provided in these with with a mean of 34.71% and 68.73% in the animals, 42.18% and 72% in the food products, and 7.77% and 25.84% in the human samples, respectively. These data demonstrated an excessive rate of C. coli and C. jejuni prevalence in Iran, especially in broilers and poultry meat. During this period, most of the studies mentioned the C. jejuni as the predominant bacteria, which is detected in several animal products or human specimens in different regions of the country, especially in industrial cities such as Tehran, Isfahan, and Shiraz.

3.2. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns of Campylobacter

Antimicrobial susceptibility data for C. coli and C. jejuni isolates are shown in Table 3. These data reflect the 13-year period from 2004 to 2017 of sampling time in all identified studies. In this review, common antibiotics used for antibiotic susceptibility test with minimum and maximum resistance for C. coli and C. jejuni were selected from various studies and then listed in Table 3. In all of the studies, C. coli and C. jejuni isolates showed the lowest resistance to gentamicin, neomycin, and chloramphenicol (0% - 10%). According to the studies, C. coli showed the highest resistance to streptomycin (4.3% - 89.7%), ampicillin (4.3% - 82%), amoxicillin (3.7% - 79.5%), and erythromycin (0% - 40%) in comparison with the C. jejuni. Moreover, seven studies reported a similar resistance to the colistin (0% - 35%). The maximum resistance rate in C. coli and C. jejuni was due to ciprofloxacin (29% - 100%), nalidixic acid (13% - 100%), and tetracycline (18% - 94%). In summary, these data demonstrate a high resistance rate to these antimicrobial agents.

4. Discussion

Campylobacter is one of the most common bacterial causes of food-borne diseases. Unlike in humans, the intestinal tracts of all avian, including turkey, chicken, and quail, are suitable environments for Campylobacter colonization. Although it is often at a high level but brings little or no disease (11, 47). Since the numbers of cases of Campylobacteriosis have increased in North America, Europe, and Australia and epidemiological data from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East are still incomplete (48, 49), we performed this review to investigate the distribution of prevalence rates and antibiotic-resistant of C. coli and C. jejuni using approved, published studies in Iran for the period of 2004 to 2017. According to these results, Campylobacter spp. is one of the most important bacteria isolated in slaughterhouses with high resistance to different antimicrobial agents. Besides, the prevalence of C. coli and C. jejuni in animal sources (34.71%, 68.73%), food products (42.18%, 72%), and human clinical specimens’ (7.77%, 25.84%) showed high rating, respectively. In Iran, the overall mean prevalence of Campylobacter in human clinical specimens ranged from 7.77 to 25.84%, which is within the ranges reported in low- and middle-income countries. For instance, between 2005 and 2009, 14.9% of patients in Beijing, China, were reported to be positive for Campylobacter species (50, 51). However, the prevalence of Campylobacter in animal sources and food products was higher or lower than that reported values in Korea and the USA (52, 53). This variation may be attributed to the fact that Campylobacteriosis is hyperendemic in these countries and due to the poor sanitation, proximity of humans and domestic animals, various sampling sizes, employing various laboratory techniques, and the effect of geographical characteristics in different studies (30, 32). Similar to other countries, human infections caused by C. coli and C. jejuni, which was detected in identified studies, typically results from consuming undercooked poultry or via cross-contamination from the inadequate handling of poultry or avian products. For example, between 1992 and 2009, 143 outbreaks were reported in England and Wales, United Kingdom. Of these, 114 were due to contaminated food or water (54). Therefore, studies recommended that the incidence of Campylobacter spp. in the animal product, especially in avian, can be reduced by following public biosafety principles in poultry farms and pre-slaughterhouse carcasses processing. Besides, properly cooking is necessary for killing infectious agents. Since there are no internationally agreed criteria of antibiotic susceptibility testing and breakpoint assessment for Campylobacter spp., it is difficult to understand the available information and draw a conclusion (55). In developing countries like Iran, most of the antimicrobial agents in the human pharmacopeia are also used in the poultry industry and there is a significant concern about the increasing antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter spp. isolated from both humans and animals. For instance, the tetracycline class is the most commonly used antibiotic in domestic animals farming for treatment aims, because of its low cost and efficacy; however, it has led to a high tetracycline resistance in Campylobacter spp. isolated from different animal samples in Iran (30, 56-58). This resistance is comparable with the findings reported by studies performed in Poland and the USA, as well as the collective estimate prevalence worldwide (94.3%) (55, 59, 60). In this review, we observed a high rate of tetracycline, nalidixic acid, and ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter spp., as reported by studies performed in various regions of the country from 2004 to 2017. Similar to our evaluation in 2013, the study by Wieczorek (61) found that C. coli had higher levels of resistance to ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, tetracycline, and streptomycin. In France, a 5-year survey of fecal samples from cattle recovered Campylobacter species showed an increase in the rates of resistance to fluoroquinolones (29.7 to 70.4%) (62). To be specific, these differences in occurrences of antimicrobial resistance reflect the widespread usage of these antimicrobial agents for the prevention of poultry diseases. It worth noting that these antibiotics may be inappropriate for empirical therapy in many cases. In the current review, all C. coli and C. jejuni isolates were susceptible to gentamicin. In addition, low levels of gentamicin resistance are potentially owing to the lower administration of this antimicrobial agent in poultry, duck, and goose rearing.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this review indicate that consuming poultry meat, broiler, duck, goose, camel, beef, buffalo, cow, and turkey is a potential public health risk regarding food-borne Campylobacteriosis and C. jejuni remains a predominant species in Iran. So antimicrobial resistance studies performed during 2004 and 2017 showed a high rate of resistance to several antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, and tetracycline, except for gentamicin, neomycin, and chloramphenicol that had a low resistance rate. The surveillance of Campylobacter spp. and monitoring of antimicrobial agent usage in aviculture and stockyard would be useful for reducing the risk of meat contamination. Moreover, these data may assist in revising treatment guidelines as well as decreasing the antimicrobial-resistant in human societies.