1. Background

Oral health is a key factor of overall health and fundamentally influences the quality of life. Despite the direct influence of oral health on general health, its importance is often ignored in occupational health (1-4). Poor oral health is recognized as a silent epidemic (5). Oral health is a very important issue not only in personal life but also is strongly connected to work performance (6). Poor oral health is associated with risk factors and certain systemic diseases, including diabetes, lung and heart disease, stroke, and premature birth. In fact, anyone who experiences oral disease is aware of the impact of this condition on their working capacity, including the loss of productivity and functioning (presenteeism) in the workplace (1, 7). Numerous individual and structural barriers have been identified to oral health, including socio-cultural factors, physical accessibility to the proper dentist and dental services, fear of dentistry, lack of expertise of healthcare providers, lack of oral health knowledge and attitude of patients and healthcare providers, lack of time for patients and caregivers, lack of dental insurance, and financial barriers (8-17).

Oral health-related knowledge is considered the core determinant of health (18, 19). There is also a significant relationship between employees’ health conditions and job performance, i.e., all factors contributing to oral diseases and oral health inequalities affect work performance (20-24). In addition to oral-health-related knowledge, self-efficacy and attitude have been found to be powerful factors characterizing dental health behavior (25, 26). Self-efficacy refers to a person’s belief in his/her ability to perform a particular behavior. Attitude refers to an individual’s psychological construct (beliefs, thoughts, and attributes) that is associated with an object and can vary from extremely negative to extremely positive. Knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and behavior are interrelated, and the level of oral health behavior is associated with the level of knowledge and perception of individuals towards oral health (27, 28).

Healthcare employees are one of the most influential individuals shaping oral health behavior. Similarly, healthcare employees are the chief constituent of the healthcare system of any community. Adequate knowledge regarding oral health is directly associated with general health. Studies have shown that healthcare employees with appropriate oral health knowledge and behavior can improve and maintain proper oral healthcare (29). Employees’ oral health behaviors are a strong predictor of behavior change in patients (30). Healthy healthcare employees can better and knowledgeably support their patients. There is relatively little available literature about the oral health of healthcare employees (4, 31, 32). Current evidence suggests that improving oral health knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of healthcare employees is necessary for the healthcare system (32).

The relationship between the educational and socio-economic status of healthcare workers and their dental visits has been examined in previous studies. Some studies have suggested that people with higher education and economic status usually have better oral health habits and oral hygiene practices (32, 33). Regular dental visits have been recommended for optimal oral health. A previous study in Japan specified that only 3% of employees had regular dental visits (34). In another study, nurse practitioner students showed poor hygiene behavior and lower experience of dental visits than dental hygiene students, indicating the effect of oral health education programs on dental hygiene behaviors (35).

To increase the level of people’ knowledge, attitude, and behavior, the appropriate educational programs must be designed according to available information, models, and theories of health education and health promotion. Identifying the level of knowledge, attitude, behavior, and self-efficacy of the targeted community is considered the basis of oral health promotion programs (36).

2. Objectives

Since poor oral hygiene and oral diseases put a considerable burden on individuals, families, and the community, especially among health workers and due to the importance of oral health knowledge and skills of health workers in the promotion of oral health and the well-being of the community, the present study examined the oral health-related knowledge, attitude, behavior, and self-efficacy among healthcare professionals.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The present descriptive-analytical study was conducted in 2021. A total of 404 (female = 234, male = 170) employees from all health personnel of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (AJUMS) participated in the study. Ahvaz is the capital of Khuzestan province (southwestern Iran) (36). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age between 25 – 55, (2) no history of oral diseases at the moment.

A full list of employees was prepared, and the desired samples were selected according to a table of random numbers method. The WhatsApp messenger was used for messaging purposes. The questionnaire link (https://survey.porsline.ir/s/aDpC331) was sent to all the employees through WhatsApp. The participants were required to answer all questions. The incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the study. The employees were assured that their names or any information, which may reveal their identity, would not be given publicly.

3.2. Sample Size Estimation

Using the following formula, the sample size was considered according to other studies and the sample size formula: n = (z1 − α2) 2 × p (1 − p)/d2) where α: 5%, d: 6%, p: 50%. Finally, a total of 400 (considering 50% for sampling method) were selected for the study.

3.3. Measures

Data collection tools included a questionnaire consisting of a series of questions, including socio-demographic questions (gender, age, marital status, number of children, occupation, health insurance and supplementary insurance, education level, spouse education, and career), medical history (cardiovascular disease, allergies, liver and kidney disease, diabetes, infectious disease, gastrointestinal disease, osteoarthritis, thyroid disease, hypertension, history of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, blood transfusion, history of hospitalization and medication, and addiction). Additionally, employees’ oral health knowledge and attitude as well as their levels of self-efficacy and behavior were measured as follows: knowledge (nine true / false questions (0 - 1 point each) about oral hygiene habit and oral health knowledge, including proper toothbrushing, the pros and cons of fluoride on teeth, and tooth flossing questions; a higher score indicated better status), attitude (11 questions with five-point scale (1 - 5 scale ) ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree which designed to measure the attitude of the participants, e.g., the role of tooth brushing in the prevention of tooth decay and the role of flossing in reducing bad breath; a higher score indicated a positive attitude), behavior (13 yes/no questions (0 - 1 point each), including do you brush your teeth twice a day?, do you floss your teeth every day to keep your mouth healthy?, do you visit your dentist at least once a year?, etc.; a higher score indicated more favorable oral health behaviour), self-efficacy (10 questions with five-point scale (1-5 scale) ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree like I brush my teeth regularly even on busy days, I floss regularly, even when I feel angry or anxious, etc. ; a higher score indicated higher level of self-efficacy).

3.4. Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire was confirmed to be valid and reliable according to the previous study (36). The CVI and CVR of the questionnaire were 0.8. Cranach’s Alpha-level for the sub-scales was found to be satisfactory: knowledge = 0.8, attitude = 0.83, self-efficacy = 0.85, and behavior = 0.79.

3.5. Data Analysis

The independent samples t-test was used to compare the means of two independent groups. Data were analyzed applying the t-test, ANOVA, and logistic regression. The normality of the data was assessed. The result showed that data were normally distributed. Bivariate analysis was performed with demographic variables and knowledge, attitude, behavior, and self-efficacy to explore the factors affecting behaviors. In the next step, significant variables were entered into the regression model. An analysis of residuals confirmed the assumptions of linearity. It should be mentioned that collinearity was checked and was negative. Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-value less than 0.05 at the final stage was considered statistically significant. Ethical considerations: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Ethics committee reference number: IR.AJUMS.REC.1399.797).

4. Results

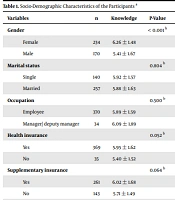

A total of 404 (female = 234, male = 170) employees of AJUMS participated in the study. The mean age of the participants was 37.38 ± 6.75. The socio-demographic information of the respondents is presented in Table 1. There was a significant difference between women’s and men’s levels of knowledge (P < 0.001), attitude (P = 0.004), behavior (P = 0.023), and self-efficacy (P < 0.001). The mean score of knowledge, attitude, behavior, and self-efficacy of women was more than men (Table 1). The result showed a significant correlation between spouse education and attitude. Similarly, a positive correlation was found between spouse occupation, knowledge, and attitude, i.e., employees with a higher education spouse level (PhD) had a better attitude (P = 0.001), and employees with spouse career support (compared to the housewife and unemployed) had better knowledge (P = 0.001) and attitude (P = 0.006).

| Variables | n | Knowledge | P-Value | Attitude | P-Value | Behavior | P-Value | Self-efficacy | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | < 0.001 b | 0.004 b | 0.023 b | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Female | 234 | 6.26 ± 1.48 | 48.67 ± 4.92 | 6.02 ± 2.22 | 6.48 ± 3.09 | ||||

| Male | 170 | 5.41 ± 1.67 | 47.10 ± 5.94 | 5.47 ± 2.65 | 5.24 ± 3.53 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.804 b | 0.686 b | 0.436 b | 0.064 b | |||||

| Single | 140 | 5.92 ± 1.57 | 47.85 ± 5.38 | 5.90 ± 2.50 | 3.36 ± 2.26 | ||||

| Married | 257 | 5.88 ± 1.63 | 48.08 ± 5.47 | 5.70 ± 2.40 | 5.71 ± 3.36 | ||||

| Occupation | 0.500 b | 0.828 b | 0.064 b | 0.410 b | |||||

| Employee | 370 | 5.89 ± 1.59 | 47.99 ± 5.39 | 5.72 ± 2.43 | 5.92 ± 3.34 | ||||

| Manager/ deputy manager | 34 | 6.09 ± 1.89 | 48.21 ± 5.86 | 6.52 ± 2.33 | 6.41 ± 3.27 | ||||

| Health insurance | 0.052 b | 0.911 b | 0.436 b | 0.766 b | |||||

| Yes | 369 | 5.95 ± 1.62 | 48.02 ± 5.46 | 5.82 ± 2.44 | 5.97 ± 3.36 | ||||

| No | 35 | 5.40 ± 1.52 | 47.91 ± 5.11 | 5.48 ± 2.28 | 5.80 ± 3.05 | ||||

| Supplementary insurance | 0.064 b | 0.705 b | 0.261 b | 0.909 b | |||||

| Yes | 261 | 6.02 ± 1.68 | 48.09 ± 5.67 | 5.89 ± 2.46 | 5.95 ± 3.41 | ||||

| No | 143 | 5.71 ± 1.49 | 47.87 ± 4.95 | 5.61 ± 2.36 | 5.98 ± 3.19 | ||||

| Education | 0.009 c | 0.551 c | 0.160 c | 0.707 c | |||||

| Diploma | 5 | 5.40 ± 1.14 | 49.00 ± 4.63 | 5.20 ± 3.19 | 5.20 ± 4.60 | ||||

| Associate degree | 29 | 5.10 ± 1.63 | 46.65 ± 6.48 | 5.34 ± 2.79 | 5.24 ± 3.54 | ||||

| BS | 200 | 5.84 ± 1.46 | 47.85 ± 5.24 | 5.62 ± 2.30 | 5.96 ± 3.35 | ||||

| MS | 115 | 6.01 ± 1.62 | 48.45 ± 5.47 | 5.90 ± 2.46 | 6.19 ± 3.38 | ||||

| PhD | 55 | 6.40 ± 1.99 | 48.29 ± 5.47 | 6.45 ± 2.48 | 5.92 ± 2.96 | ||||

| Spouse education | 0.096 c | 0.001 c | 0.464 c | 0.861 c | |||||

| Diploma | 42 | 5.31 ± 1.61 | 46.16 ± 6.30 | 5.45 ± 2.56 | 5.28 ± 3.43 | ||||

| Associate degree | 24 | 5.67 ± 1.31 | 46.58 ± 5.16 | 5.92 ± 2.67 | 5.67 ± 2.90 | ||||

| BS | 110 | 5.91 ± 1.77 | 47.95 ± 5.89 | 5.62 ± 2.46 | 5.92 ± 3.52 | ||||

| MS | 50 | 6.22 ± 1.45 | 50.06 ± 4.87 | 5.90 ± 2.22 | 5.80 ± 3.28 | ||||

| PhD | 14 | 6.07 ± 1.68 | 49.78 ± 4.00 | 6.21 ± 1.67 | 5.21 ± 2.81 | ||||

| Spouse occupation | 0.001 c | 0.006 c | 0.154 c | 0.157 c | |||||

| Self-employed | 33 | 5.91 ± 1.28 | 47.39 ± 4.86 | 5.85 ± 2.11 | 6.00 ± 3.45 | ||||

| Employee | 139 | 6.15 ± 1.59 | 49.04 ± 5.23 | 5.93 ± 2.35 | 6.04 ± 3.34 | ||||

| Housekeeper | 73 | 5.36 ± 1.59 | 46.37 ± 6.22 | 5.09 ± 2.35 | 4.88 ± 3.26 | ||||

| Unemployed | 4 | 3.75 ± 2.22 | 42.75 ± 10.62 | 5.75 ± 4.50 | 4.75 ± 4.11 | ||||

| Retired | 3 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 47.92 ± 5.69 | 4.67 ± 0.58 | 6.67 ± 4.16 |

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants a

There was a significant correlation between the educational degree and respondents’ knowledge. However, no significant relationship was found (P = 0.009) between the educational degree, attitude, and behavior of the respondents. There was a significant correlation between the number of children and self-efficacy, i.e., the more children there were, the higher the level of self-efficacy. In univariate analysis, the level of knowledge, attitude, behavior, and self-efficacy was associated with dental visits. However, in multiple regression, the associations were not significant. In this study, multivariate analyses were performed using logistic regression. The oral-health-related background factors (independent variables) were regressed against the dependent variable (visiting the dentist) (Table 2).

| Independent Variables | B | S.E. | P-Value | OR | 95% C.I. for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender (RC; female) | 0.11 | 0.266 | 0.676 | 1.12 | 0.664 | 1.881 |

| Marital status (RC; single) | -0.86 | 0.290 | 0.003 | 0.42 | 0.240 | 0.747 |

| Occupation (RC; employee) | 0.52 | 0.477 | 0.273 | 1.69 | 0.662 | 4.293 |

| Health insurance (RC; yes) | -0.25 | 0.449 | 0.570 | 0.78 | 0.321 | 1.867 |

| supplementary insurance (RC; yes) | 0.13 | 0.291 | 0.655 | 1.14 | 0.644 | 2.016 |

| Age | -0.03 | 0.023 | 0.205 | 0.97 | 0.929 | 1.016 |

| Education (RC; diploma) | ||||||

| Education (1) | -2.66 | 1.273 | 0.037 | 0.07 | 0.006 | 0.850 |

| Education (2) | -2.32 | 1.167 | 0.047 | 0.10 | 0.010 | 0.970 |

| Education (3) | -2.02 | 1.183 | 0.088 | 0.13 | 0.013 | 1.347 |

| Education (4) | -1.93 | 1.214 | 0.112 | 0.15 | 0.013 | 1.568 |

| Diabetes (1) | -0.31 | 0.951 | 0.748 | 0.74 | 0.114 | 4.749 |

| Taking medicines (RC; no) | -0.36 | 0.458 | 0.436 | 0.70 | 0.285 | 1.718 |

| Osteoarthritis (RC; no) | -0.49 | 0.601 | 0.410 | 0.61 | 0.188 | 1.979 |

| Gastrointestinal disease (RC; no) | -1.71 | 0.645 | 0.008 | 0.18 | 0.051 | 0.641 |

| Thyroid disease (RC; no) | 0.41 | 0.399 | 0.311 | 1.50 | 0.685 | 3.273 |

| Abnormal blood pressure (RC; no) | -0.32 | 0.632 | 0.612 | 0.73 | 0.210 | 2.505 |

| Allergies (RC; no) | 0.12 | 0.629 | 0.856 | 1.12 | 0.327 | 3.846 |

| knowledge | -0.12 | 0.083 | 0.163 | 0.89 | 0.758 | 1.048 |

| Attitude | 0.03 | 0.025 | 0.189 | 1.03 | 0.984 | 1.084 |

| Behavior | 0.01 | 0.060 | 0.918 | 1.01 | 0.895 | 1.131 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.04 | 0.045 | 0.441 | 1.04 | 0.948 | 1.131 |

| Constant | 1.55 | 1.813 | 0.392 | 4.72 | ||

Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis of Oral-Health-Related Background Factors (Independent Variables) Against the Dependent Variable (Visiting the Dentist)

The results showed that in the marital status variable (OR: 0.42, P-value = 0.003), the chance of going to the dentist in the married employees was 0.42 compared to the single employees, i.e., the chance of going to the dentist in the single employees (1/0.42 = 2.38) was 2.38 times more likely than the married employees. The results also showed that in the education variable, a significant difference was found between associate degree (OR: 0.07, P-value = 0.037), bachelor’s degree (OR: 0.10, P-value = 0.047), and diploma (the chance of visiting a dentist in the associate and bachelor degree was equal to 0.07 and 0.10, respectively, i.e., the chance of visiting the dentist in employees with the diploma degree was 14 times (1/0.07 = 14) more likely than the bachelor degree and 10 times (1/0.10 = 10) more than the PhD degree.

Among the underlying diseases, gastrointestinal diseases (OR: 0.18, P-value = 0.008) showed a significant correlation with dental visits, i.e., the chance of visiting the dentist in employees with gastrointestinal diseases was 0.18 compared to normal employees (the chance of visiting the dentist in employees with the normal condition was 5.5 times (1/0.18 = 5.5) more likely than employees with gastrointestinal diseases.

5. Discussion

Physical health, including oral health, facilitates employees’ physical and mental health and improves working conditions at the enterprise level. The employees’ oral health knowledge and behaviors are the main influencing factors to oral health (30, 32, 35). The present study examined the perception of AJUMS employees toward oral health and dental visit. The relationship between knowledge, attitude, behavior, and self-efficacy of employees and some demographic and socio-economic variables was analyzed. In this study, the knowledge, attitude, behavior, and self-efficacy of women were more than men. Kawamura et al. suggested that females generally have healthier behavior (brushing frequency, dental visits, and dietary patterns) than males (31). Moreover, women had more restored teeth. The reason could be explained because women have a propensity to stay young and look beautiful, so they are more interested in improving their dental appearance (31).

Hamasha et al., 2018 found no significant gender difference in beliefs; however, they suggested that females, in general, acted more positively toward oral health than males (37). Kateeb concluded that females had more positive dental health attitudes and behaviors than men (38). Frequent consumption of simple carbohydrates and positive attitude toward visiting the dentists in women encourage them to actively maintain good oral health and regular dental visits (39, 40). Some studies have shown that men and women do not have the same dental priorities, indicating the men’s knowledge of the need for good oral health and taking actions that promote all men to follow regular dental care (37). However, some studies have found no significant difference in oral health perception among males and females. Oberoi et al. found no statistically significant difference in oral hygiene perception among males and females. The reason could be explained due to socio-cultural differences (41). Movahhed et al., in a study on 134 healthcare personnel, found no significant relationship between knowledge, attitude, self-reported and simplified oral hygiene index scores, and demographic variables such as age, gender, occupation, contract type, and workplace (32).

This study also showed a significant relationship between the level of education and the knowledge of employees, i.e., employees with higher education levels had more knowledge. Similarly, Movahhed et al. found a significant correlation between education level and knowledge, attitude, and simplified oral hygiene index scores and suggested that healthcare personnel with higher education levels had more knowledge about oral health which was consistent with the results of the present study (32). Bomfim et al. also showed a significant association among Oral Health Impact Profile-14, education level, work ability index (WAI), gender, job title, and age of employees (7). Similar studies have shown a positive relationship between education level and oral health knowledge (42, 43). The evidence suggested that lack of adequate education and training, as well as lack of access to adequate insurance, were the major barriers to oral health services (42, 44).

On the other hand, no significant relationship was found between the employees’ educational degree, attitude, and behavior. This indicates that employees with higher education, despite more knowledge, do not necessarily show a better oral health attitude and behavior. Savage et al. reported that poor oral health behavior was not necessarily associated with poor oral health knowledge and suggested that socio-cultural factors, including lack of oral health prioritization contributed to poor oral health behavior (9).

Several studies found that negative attitudes and misconceptions of employees can be a barrier to turning knowledge into behavior, which implies that health education interventions, in addition to increasing knowledge, can also improve attitude and behavior (11-14). Movahhed et al. also showed that healthcare personnel’s oral knowledge level and attitude were better than their oral health behavior, which confirms the consistency between the knowledge and attitude (32). One of the major challenges in health behaviors, despite having knowledge, is to create a positive attitude and behavior. Therefore, despite considerable knowledge, establishing a positive attitude and mindset is essential to develop long-term health behavior, especially in work environment (45, 46).

This study also showed a significant correlation between oral health attitude and spouse education and career, i.e., employees with a higher education spouse level and higher job rankings had better attitudes towards oral health. In this study, the regular dental visits were more observed in single employees (compared to married) and employees with diploma qualifications (compared to bachelor’s and PhD degrees). According to the results of this study, employees with diploma qualifications due to lack of knowledge had poor oral health and experienced more pain which prompted them to refer more to the dentist. Furthermore, the results of the study showed a positive correlation between oral health and overall health. An overall decline in dental visits was observed in employees with gastrointestinal diseases compared with normal employees.

Kawamura and Iwamoto showed that 76 percent of Japanese employees delayed visiting a dental professional until they had toothache, and 60 percent delayed visiting a dental professional even they found a decayed tooth (47). Walker and Jackson showed that nurse and nurse practitioner students had fewer dental visits and poorer hygiene practices than dental hygiene students and concluded that oral health-related beliefs and behaviors should be encouraged early in nursing education, which implies the necessity of community-based oral health education program (35). Walid et al., 2004 showed that 20% of nurses in Lesotho never had dental visits and the nurses believed that they should visit dentists only when they need treatment; however, they specified optimistic attitudes toward the establishment of oral health education and oral hygiene practices (48). The significance and benefits of regular dental visits for overall health have been emphasized by several studies (29, 33). Moreover, regular dental visits can keep people safe from future extensive and expensive dental procedures.

This study suggested that single employees had more dental visits than married employees. The reason would be due to the fact that single employees have lower living costs and can save more money for dental visits. Furthermore, single employees do not have hectic and busy schedules or mismanaged lifestyles, so they have more time to visit a dentist. Generally, the main causes of poor oral health behavior are time constraints, high dental treatment costs, misconceptions, lack of skills of dental care providers, dentophobia, and insufficient access to oral healthcare services and dental specialists (9, 49, 50).

5.1. Limitations of the Study

This study had some limitations. First, self-reporting questionnaire in data collection was considered the limitation of the study. Second, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it was not possible to investigate the cause-and-effect relationship between the variables. Therefore, longitudinal studies are recommended. Similarly, clinical examination was not possible due to the complexity of COVID-pandemic conditions. Therefore, additional oral clinical examinations are recommended among healthcare professionals.

5.2. Conclusions

Demographic characteristics and oral health knowledge, attitude, and behavior of employees are intercorrelated with the frequency of dental clinic visits. Oral health promotion programs can maintain good oral health among workers. Tailoring oral health education is recommended to improve oral health status of healthcare professionals.