1. Background

Heart disease is the most frequent and important cause of mortality in the world, being responsible for 18 million annual deaths. Estimates suggest that by 2030, 44% of the world's population will suffer from heart disease (1). Heart failure, as the final outcome of all cardiac diseases, has a high mortality rate in low and middle-income countries (2). This health problem has affected around 26 million people worldwide, with a prevalence rate of 4.3% in the general population and up to 20% in people older than 75 years (3). The incidence of heart failure in Iran was about 8% of the total population, and one-year mortality was 18.2%, as reported by Ahmadi et al. (4-6). According to the latest study, heart disease in Kermanshah city accounted for 44% of the total deaths, and the mean rate of one-year mortality was 8% (15% in older and 4.2% in middle-aged patients), which is roughly equivalent to global world statistics (2 - 20% based on age) (2, 7, 8).

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a complex clinical syndrome where the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the needs of the body. Any disorder in the heart muscle that impairs the systemic circulation of blood causes this disease. Patients usually refer to dyspnea, fatigue, reduction of endurance, and retention of fluid, which is caused by pulmonary and environmental congestion (9). Congestive heart failure has different types which are the most common in the left ventricle (LV) failure. As known, LV failure is often diagnosed by reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF), which is the result of dividing the stroke volume on the left ventricle end-diastolic volume (10). Heart failure patients have numerous psychological and physical symptoms, such as chest pain, dyspnea, anxiety, and depression, that affect their quality of life (11). Heart failure has an inseparable relation with quality of life, and patients who have a higher quality of life are more likely to have lower mortality and morbidity.

Quality of life consists of 4 components: (1) Physical health, including chest pain, sleep quality, rest, and ability to perform daily activities; (2) mental health, including appearance, positive and negative emotions, memory, concentration, and self-confidence; (3) social relations, including personal relationships, social support, and sex activity; and (4) the environment including financial status, home environment, information access, and participation in social activities (12). In the meantime, mental disorders such as anxiety have a great impact on the performance and social relations of heart patients. Psychological disorders should be considered in these patients as a serious risk factor (13). Several studies have stated the relationship between heart failure and quality of life (14, 15). Peletidi et al. and Heo et al. have shown a strong bond between heart failure and quality of life (16, 17).

Although there are several therapeutic interventions to reduce the physical symptoms of cardiac patients and consequently increase the quality of life, it is determined that if we ignore the symptoms and mental disorders in these patients, our efforts to increase the quality of life will not be successful. Therefore, it is necessary to apply well-known psychological training, such as social problem solving skills training (SPSST), in these patients to improve their mental and psychic problems (18-20). Teaching SPSST is a well-known cognitive-behavioral approach to control mental disorders and improve quality of life (21). First, the impact of problem-solving skills training on the mental disorders of patients was suggested by D’Zurilla and Goldfried. The steps of this intervention include (1) general orientation to the problem; (2) description and structuring of the problem; (3) introduction of various solutions; (4) evaluation and decision-making; and (5) using the best solution (22). No studies have been done on patients with heart failure so far. However, a similar study was done by Polat and Simsek, which measured the effectiveness of teaching problem-solving skills for depression and the quality of life of cardiac patients during hospitalization (23). Therefore, due to the lack of studies in this field, the prevalence of heart disease in society, and the low quality of life of these patients, this study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of social problem-solving skills training on QOL in congestive heart failure patients.

2. Objectives

Due to the large number of cardiac patients in society, the low quality of life in most of these patients, and the insufficient efficacy of medical and drug interventions in this regard, this study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of SPSST on the quality of life of congestive heart failure patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Population

Our sample was selected through convenience sampling and was allocated into control and experimental groups randomly. Among 100 heart failure patients referred to Imam Ali Heart Center in Kermanshah, 20 patients were selected according to inclusion criteria and randomly divided into control and experimental groups. Inclusion criteria included: (1) A cardiologist confirmation of LV ejection fraction under 45% (for all patients, a cardiologist performed echocardiography, and patients with LV ejection fraction of 45% were selected, and LVEF is the result of dividing the stroke volume of the heart on the LV end-diastolic volume); (2) the presence of congestive symptoms with the diagnosis of a heart specialist (consisting of dyspnea (NYHA FC:1-2), edema, and intolerance of exercise more than routine activities); (3) lack of serious physical and mental disorders; (4) middle school degree education; and (5) quality of life score below 60 based on the questionnaire of quality of life. The exclusion criteria included the absence of other non-cardiac chronic diseases, voluntary withdrawal from the study, and absence from more than 2 training sessions.

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.2.1. Informed Consent

Ethical considerations included filling out the written consent form, information confidentiality in all stages of the study, voluntary withdrawal from the study at any stage, and ensuring that people do not experience complications or risks in the study.

3.3. Research Instruments

To measure the quality of life, a World Health Organization (WHO) group was obliged to construct a questionnaire. The result of this group was a 100-item life questionnaire (WHO QOL-100). A few years later, a short-form questionnaire was developed. Then, the quality of life questionnaire was summarized, and the short questionnaire of quality of life was developed.) WHO QOL-BREF scale (2). This scale, which included 26 questions, was adopted in 1996 by a group of global health experts. The questionnaire has four sub-scales and a total score. These include physical health (example: How much does the physical pain stop you from doing things? Very well, well, middle, very bad, bad), mental health (example: How many times do you get a mood like frustration and depression and anxiety?), social relationships (example: How happy are your friends and acquaintances?), the health of the surrounding environment (example: How much secure is your feeling in your daily lives?), and an overall score (24). First, for each subscale, a raw score is obtained, and then the score is placed in the formula, and the standard score of quality of life is obtained, that is, between 0 and 100. A higher score indicates a higher quality of life. (25). The reliability of the questionnaire was 0.86, and the validity was 0.72. The reliability and validity of the Iranian version of the quality of life questionnaire were 0.92 and 0.78, respectively, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient was acceptable (α > 0.75) (26, 27).

3.4. Intervention Method

After the enrollment of the subjects in the study, the QOL questionnaire was completed by the patients. Then, they were randomly divided into two control and experimental groups (n = 10), and the control group received routine care during the study. Nevertheless, for the experimental group, in addition to routine care, intervention was done.

We presented in 10 sessions the SPSST instructions, which were prepared by the Psychology Department of Islamic Azad University of Kermanshah based on previous valid studies. The questionnaires were completed for the two groups again immediately and three months after the intervention. All training sessions were based on six stages of the D’Zurilla and Goldfried model (1971) (22): General orientation, definition and formulation of solutions, generating alternative solutions, decision-making, solution implementation, and review (Table 1).

| Sessions | Description |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Introduction, communicating with members, introduction to plan objectives, Grouping and setting group provisions on the basis of participants' agreement |

| Session 2 | Introducing problems and problem-solving, familiarity with everyday problems and accepting the nature of experiencing difficulties in life, belief in the effectiveness of problem-solving in dealing with problems, positive orientation towards problems |

| Session 3 | Acquaintance with automatic thoughts, ability to minimize preventive or impulsive actions, understanding the everyday problems of life, reinforcement of optimism, building constructive thinking |

| Session 4 | Self-efficacy beliefs, reinforcement of positive self-efficacy beliefs in approaching the problems, changing attitudes towards the problem, increasing the individual's empowerment to reduce impulsive and avoidant attitudes, changing the attitude toward the problem |

| Session 5 | Training to define the problem and its exact expression (the first step of the rational solution-solving style), data collection relative to the problems, the definition of the problem accurately and objectively, and specifying a position that converts a position to a problematic position. |

| Session 6 | Reviewing the previous sessions, creating alternative solutions (the second phase of the rational solution-solving style), identifying and instructing possible solutions to problems and everyday life problems, providing diversified solutions using brainstorming for a problem, expanding the use of adaptive solutions and reducing the willingness to use habitual solutions. |

| Session 7 | Decision-making, evaluating the way ahead and its consequences, training chain behavior and selecting the best way to solve or adapt, analyzing the cost |

| Session 8 | Reviewing the previous sessions, training, and approving the solution (third stage of social problem-solving skills), performing a solution, controlling its results, judging its effects, troubleshooting in the event of non-success |

| Session 9 | Evaluating and selecting the best option (final option) to solve the problem, training the stages of problem-solving, presenting a worksheet in difficult situations, identifying and defining the problem, presenting the solution, cost-benefit analysis, and selection of feedback and providing feedback |

| Session 10 | Reviewing the procedures and stages of the training given in the previous sessions and evaluating the performance of the stages with the role-playing method, evaluation by other stakeholders |

Summary of Training Sessions of Social Problem Solving Skills Training

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from the study in all stages were entered into SPSS (ver:23) software. They were checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess the distribution of data and the Levene test to assess the homogeneity of the variances. Then, the data were analyzed by t-test and covariance analysis at a significance level of less than 0.05.

4. Results

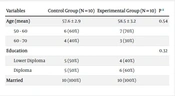

Demographic information of the participants is given in Table 2, showing no significant difference in terms of age, education, and marital status between the groups.

| Variables | Control Group (N = 10) | Experimental Group (N = 10) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 57.6 ± 2.9 | 58.5 ± 3.2 | 0.54 |

| 50 - 60 | 6 (60%) | 7 (70%) | |

| 60 - 70 | 4 (40%) | 3 (30%) | |

| Education | 0.32 | ||

| Lower Diploma | 5 (50%) | 4 (40%) | |

| Diploma | 5 (50%) | 6 (60%) | |

| Married | 10 (100%) | 10 (100%) |

Demographic Data of Control and Experimental Groups

Table 3 shows the mean values of the studied variable (i.e., QOL) before, after, and during the follow-up period. The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene tests show that the data distribution in both groups and all stages was normal. Also, variances were homogeneous in all stages (P > 0.05), so the t-test and ANCOVA were used to analyze the data.

| Variable | Groups | Stage | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| QOL | Control | Pre-test | 51.2 ± 10.7 |

| Post-test | 52.3 ± 10.1 | ||

| Follow-up | 51.3 ± 8.9 | ||

| Experimental | Pre-test | 51.4 ± 10.5 | |

| Post-test | 59.8 ± 6.6 | ||

| Follow-up | 55.8 ± 7.1 |

Mean and Standard Deviation of Variable

As seen in Table 4, a paired t-test was performed to compare the mean scores of quality of life within the control and experimental groups before and after the intervention and during the follow-up, showing no significant changes in the control group through stages (P > 0.05). However, there was a significant change in the experimental group after the intervention (P = 0.006) and during follow-up (P = 0.035). However, no significant difference was shown between the post-test and follow-up stages (P = 0.055) (Table 4).

| Groups | Comparison | Mean Diff. | SD of Mean Diff. | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | df | P a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Control | Pre-test/post-test | 1.1 | 3.03 | - 1.07 | 3.2 | 1.14 | 9 | 0.28 |

| Pre/follow-up | - 1 | 2 | - 2.4 | 0.43 | - 1.58 | 9 | 0.148 | |

| Post-test/follow-up | - 0.1 | 11.7 | - 8.4 | 8.2 | - 0.027 | 9 | 0.979 | |

| Test | Pre-test/post-test | 8.4 | 7.3 | 3.1 | 13.6 | 3.5 | 9 | 0.006 a |

| Pre-test/follow-up | - 4 | 3.4 | - 6.5 | - 1.4 | - 3.6 | 9 | 0.035 a | |

| Post-test/follow-up | - 4.4 | 5.6 | - 8.4 | - 0.37 | - 2.4 | 9 | 0.055 | |

Paired t-Test for Comparison of Quality of Life Mean Scores Within Control and Experimental Groups

As seen in Table 5, an independent t-test was performed to compare the mean scores of quality of life between the control and experimental groups before and after the intervention, showing no significant difference between the two groups (P = 096). However, there was a significant difference between the two groups after the intervention (P = 0.026) (Table 5).

| Groups | Levene's Test for Equality of Variances | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Diff | Std. Error Diff | 95% CI of Diff | ||

| Lower | Lower | ||||||||

| Control vs. exp (pre) | 0.02 | 0.88 | - 0.004 | 18 | 0.96 | - 0.2 | 4.7 | - 10.19 | 2.7 |

| Control vs. exp (post) | 0.69 | 0.415 | - 2.4 | 18 | 0.026 a | - 8.7 | 3.5 | - 16.2 | -1.1 |

Independent t-Test to Compare Quality of Life Mean Scores Between the Control and Experimental Groups Before and After the Intervention a

According to the homogeneity of the variances with the covariate effect (pre-test), the analysis of covariance was used. As shown in Table 6, the difference was significant in the quality of life score after the intervention and in the follow-up period (P = 0.01 and P = 0.045, respectively).

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOL (post-test) | 125.05 | 1 | 125.004 | 23. 73 | 0.0 |

| Error | 53.141 | 18 | 2.305 | ||

| QOL (follow-up) | 66.075 | 1 | 67.775 | 19.51 | 0.04 |

| Error | 30.436 | 18 | 2.966 |

Analysis of Covariance to Compare Quality of Life Mean Score After the Intervention and in the Follow-up a

5. Discussion

Our results showed that teaching social problem-solving skills in addition to routine medical care can be effective in improving the quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure. As another study is not exactly the same as ours, the results of our study are novel. Although there is no comprehensive study to evaluate the effectiveness of this skill on the quality of life in patients with heart failure, we do know that one of the most important factors that affect the quality of life is the psychological resilience of the patients (13, 27-29).

In line with our study, many studies have shown the effectiveness of cognitive training in improving these disorders. For example, Thoma et al. showed that teaching social problem-solving skills was effective in treating mental disorders (30). Also, the results of the studies of Omidi et al. showed the effect of teaching SPSST on anxiety, sleep quality, and depression in heart patients (31, 32). Another study showed the effect of short-term training of PSST on the quality of life of hospitalized patients with heart failure.

On the contrary, Ghasemi et al. and Bayazi et al. showed that short-term cognitive therapy had no significant effect on the mental disorders of the patients (33, 34). This disparity could be due to the gender and age difference of participants and the course of the study compared with the present study. The search for pathways that link psychiatric disorders to incident cardiac disease and subsequent cardiac events is ongoing, and many probable mechanisms have been identified (35).

The links between mental disorders and cardiac outcomes have received the most attention. Mental disorder is associated with dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, including higher levels of plasma and urinary catecholamines and cortisol, higher resting and mean 24-hour heart rates, and lower heart rate variability (25). Other studies have found elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, acute-phase proteins, chemokines, and adhesion molecules, including increased levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (36, 37).

There is also evidence that mental disorders in patients with heart failure can elevate markers of coagulation and platelet activity, especially β-thromboglobulin and platelet factor 4 (38). It was observed that patients with higher levels of these disorders had higher levels of physical symptoms such as chest pain and dyspnea. Therefore, they had a lower quality of life (39).

Cognitive-behavioral skills are effective coping strategies and promote social problem-solving, and they encourage patients to improve their morale by using behavioral activation, i.e., increasing pleasant and constructive activities (40, 41). Therefore, it can be concluded that training these skills plays a significant role in improving the mental health of heart failure patients and finally improves the quality of life of these patients.

5.1. Recommendation

A similar study is suggested to be done in different age and sex populations and those with other chronic diseases.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

There were no limits during the study.

5.3. Conclusions

Teaching SPSST can improve life quality in patients with congestive heart failure. Therefore, it should be considered in cardiac patients besides cardiac medicines.