1. Background

Humans, inherently social creatures, develop profound emotional bonds and experience grief during extended separations or the death of close ones (1). The loss of a beloved individual has been identified as one of the most distressing life events, eliciting various grief responses, with bereavement referring specifically to the loss of a loved one to death (2). Those who have suffered bereavement display a spectrum of physical, psychological, and behavioral responses to their loss (3). The traumatic impact of losing a parent can present significant psychological challenges for students, including depression, reduced self-esteem, and obstacles in establishing social connections and expressing emotions (4, 5). Liu et al. (6) noted that the death of a parent adversely affects children, leading to increased psychological distress.

Psychological distress is described as an unpleasant emotional state that emerges from challenges capable of triggering mental health disorders (7). It is a multifaceted concept associated with mental health deterioration and impaired functioning, covering symptoms such as anxiety, depression, stress, and other psychiatric conditions (8). The incidence of psychological distress among students has been on the rise over the last decade (9). Recent meta-analyses have shown prevalence rates of 33.8% for anxiety and 27.2% for depression among students worldwide (10). Numerous studies have identified psychological distress as the most common mental health problem among students, often preceding various psychological disorders and negatively impacting students' learning and academic achievements (11, 12). Moreover, the death of a parent can lead to a spectrum of psychological disorders and behavioral issues in students, further resulting in decreased motivational beliefs.

Motivation plays a crucial role in learning and is influenced by an individual's mental readiness and initial behaviors (13). Psychologists highlight the importance of motivational beliefs in explaining variations in performance levels. The presence of these motivational beliefs in students profoundly affects their learning and cognitive strategies, ultimately influencing their academic success (14). Students with positive beliefs about their abilities tend to achieve higher academic performance, whereas those with negative self-efficacy beliefs show lower motivation and poorer academic results (15). Students who have endured the loss of a parent often face increased psychological distress and reduced motivational beliefs, resulting from significant disruptions in their psychological and social functioning (16). Thus, effective therapeutic interventions are necessary to counteract these negative impacts.

Positive psychology focuses on the development of individuals rather than solely treating mental illnesses (17). Unlike traditional therapeutic methods that primarily seek to reduce symptoms of psychological disorders, positive psychology aims to refine, enhance, and optimize psychotherapeutic techniques. This approach not only relieves distress but also fosters personal growth, well-being, and happiness by highlighting positive psychological traits like hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy (18). Positive psychologists also emphasize the role of cultural influences, considering individuals as products of their cultural environments. They advocate for addressing human issues within a cultural framework (19, 20), suggesting that psychology should pay close attention to cultural beliefs along with biological aspects. Religious teachings offer resources for finding meaning and purpose in life, connecting with a higher power, and finding comfort during difficult times. These resources assist individuals in coping with emotional stress during challenging life events, thereby reducing harm (21). Studies have shown that spiritually-based positive interventions can effectively decrease anxiety, stress, depression, and behavioral problems (22-24).

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a therapeutic approach that has shown clinical effectiveness in improving various aspects of psychological disorders across different study populations (25, 26). Based on the principles of acceptance and mindfulness, ACT suggests that psychological distress results from psychological inflexibility and the tendency to avoid direct experience (27). Therefore, it emphasizes the importance of individuals learning to accept distressing thoughts and emotions, like those experienced following the loss of a parent, instead of avoiding them. This approach aims to improve psychological well-being by encouraging individuals to pursue actions that are consistent with their values, even when faced with distressing experiences. Arnold et al. (28) found that ACT was effective in addressing a wide range of psychological and behavioral issues.

This research is crucial as it targets the mental health needs of a particular group: Students who have experienced the death of a parent or a significant life event linked to psychological distress. There exists a pressing need to investigate and assess interventions, such as positive psychology training and ACT, that could effectively alleviate psychological distress and enhance motivational beliefs within this vulnerable demographic. Understanding the impact of these interventions offers critical insights for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers dedicated to supporting students in navigating the challenges of parental loss. Research on the efficacy of positive psychology training and ACT specifically for students affected by the death of a parent is sparse. This study seeks to bridge this gap by evaluating the effects of these interventions on psychological distress and motivational beliefs among these students. Previous studies might have concentrated on the general population or specific clinical groups, overlooking the distinct needs and hurdles of students grieving a parent's death. This research aims to rectify this oversight by customizing interventions to the particular requirements of this group. Furthermore, a literature review conducted by the researchers indicated that in Iran, there had been no comparison between positive psychology and ACT regarding their effectiveness on psychological distress and motivational beliefs in students grieving a parent's death.

2. Objectives

Given this background, the current study was designed to explore the effectiveness of positive psychology training and ACT in improving psychological distress and motivational beliefs among students who have lost a parent.

3. Methods

This study adopted a quasi-experimental design with a pretest-posttest follow-up format, incorporating a control group. Conducted during the academic year 2022-2023 in Ahvaz, Iran, the research targeted female secondary school students who were navigating grief due to the loss of a parent. An initial announcement for participant recruitment was made by the researchers, leading to the selection of 60 students who met the inclusion criteria through purposive sampling and had provided informed consent. These students were subsequently divided randomly into two experimental groups and one control group. The sample size for each group was established as 20 students, calculated using G-Power software based on an effect size of 1.08, an alpha level of 0.05, and a test power of 0.90. The inclusion criteria included being a secondary school student aged 16 - 18, having experienced the loss of a parent within the last year, not currently taking psychiatric medications, not participating in any psychological intervention programs in the past two months, scoring high on a psychological distress questionnaire, and scoring low on a motivational beliefs questionnaire. The only exclusion criterion was missing more than two intervention sessions. Before the interventions, a pretest evaluation was conducted with all participants. Following the interventions, post-test questionnaires were administered to all groups, with follow-up assessments occurring two months later.

3.1. Tools

3.1.1. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

Developed by Lovibond and Lovibond in 1995, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) was utilized to evaluate psychological distress. Its short form, the DASS-21, comprises 21 items divided into three subscales, each measuring one of the psychological constructs: Anxiety, depression, and stress, with seven items per factor. The responses are scored on a four-point Likert scale, where the scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 correspond to never, sometimes, often, and almost always, respectively. The aggregate scores from the DASS-21 provided by the participants were used to assess psychological distress (29). In Iran, Afzali et al. (30) validated the scale's reliability with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 for the entire scale.

3.1.2. The Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire

Developed by Pintrich and De Groot in 1990, the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) comprises two subscales that assess motivational beliefs and self-regulated learning strategies. It includes 25 items measuring self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and test anxiety, scored on a seven-point Likert scale, from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree) (31). The reliability of the MSLQ has been confirmed with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90 (32).

3.2. Interventions

The first experimental group underwent ten 90-minute sessions of positive psychology training based on religious teachings, conducted weekly. The second experimental group participated in eight 90-minute sessions of ACT. The group intervention sessions were facilitated by the first author at the Educational Counseling Center. The details of the positive psychology training package and the ACT intervention are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introducing the participants, familiarizing them with the intervention period and the rules of the sessions, and presenting explanations concerning the goals of the research |

| 2 | Discussion on appreciating God's gifts, enjoying the present moment and positive events, application of personal strengths in daily life, and assignment for participants to list three of God's gifts and three positive events in their lives to reflect on before sleep |

| 3 | Discussing the benefits of thanking God and people and asking the participants to write down an appreciation letter to someone who has done something positive |

| 4 | Familiarizing the participants with the features and effects of hope and despair from the perspective of religious teachings, stating the relationships between hope, happiness, and anxiety, and encouraging the participants to talk about their experiences concerning hope and give a positive analysis of their past experiences |

| 5 | Discussing constructive and active responses and interacting with God, oneself, others, and nature, and asking the participants to establish positive relationships with family members, friends, classmates, and school |

| 6 | Asking the participants to consider the importance of the religious recommendations about avoiding self-harm, being happy with God’s gifts, and presenting the patterns through which hope, happiness, and positive outlooks have enriched their lives, engaging in group discussions about these examples and writing down similar ones |

| 7 | Emphasizing good memories and appreciation as a sustainable form of expressing gratitude, being patient during difficulties and relying on God, and remembering the roles played by good and bad memories with a focus and emphasis on appreciation |

| 8 | Explaining the roles that effort, reliance on God, and prayer have in giving meaning to life, and asking the participants to write something about the meaning of life |

| 9 | I will speak with the participants about positive thinking in the teachings of Islam and ask them to select and talk about one of their favorite exercises presented in previous sessions. |

| 10 | Conclusion of the sessions, addressing the expression and recollection of emotions (posttest) |

The Positive Psychology Protocol Based on Religious Teachings

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introducing the participants and familiarizing them with the concepts of hopelessness and inefficacy by using the metaphor of the hole and the shovel |

| 2 | Using the "wade through the swamp," "the struggle switch," and " the ball in the pool" metaphors to teach the students that negative methods of emotion control are the cause of many of the problems |

| 3 | Explaining acceptance as the suitable control method by using the metaphors of "the unwelcome party guest," "the tug of war with a monster," and the simile " clean and dirty discomfort." |

| 4 | Using the metaphors of "bus passenger" and "parading soldiers," this session was devoted to teaching cognitive defusion to the participants and explaining to them that when something is ingrained in them, it becomes a real belief and dominates their viewpoint and thoughts. |

| 5 | Using the metaphors of "chessboard," "home," and "furniture and appliances," the participants were taught to see themselves as feeling separate from thoughts, behaviors, and labels. |

| 6 | Asking the participants to remember their values, following which they were taught the difference between values and goals. |

| 7 | The participants will be taught mindfulness, followed by exercises to live in the moment. Their values and the way they pursued them in the face of internal and external obstacles were discussed again. |

| 8 | Reviewing the participants' values, summing up ACT, teaching behavioral patterns and committed action to face and achieve values, and giving the post-test |

Description of the Training Sessions of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Protocol

3.3. Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was performed using repeated measures ANOVA in SPSS software 23, with the statistical significance threshold set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

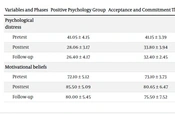

The study included 60 students who had experienced the loss of a parent, with an average age of 17.35 ± 1.72 years. The demographic characteristics of the students in both the intervention and control groups are presented in Table 3. Table 4 displays the mean and standard deviation (SD) for psychological distress and motivational beliefs among students grieving after a parent's death.

| Groups | Age, year | Duration of Loss of a Parent, (mo) | Grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenth | Eleventh | Twelfth | |||

| Positive psychology group | 16.89 ± 2.04 | 8.45 ± 3.16 | 5 (25.0) | 7 (35.0) | 8 (40.0) |

| Acceptance and commitment therapy group | 17.68 ± 1.52 | 9.80 ± 4.28 | 7 (35.0) | 6 (30.0) | 7 (35.0) |

| Control group | 17.47 ± 1.61 | 9.14 ± 3.64 | 8 (40.0) | 5 (25.0) | 7 (35.0) |

| P-value | 0.17301 | 0.261 | 0.890 | ||

Demographic Characteristics of the Students: a

| Variables and Phases | Positive Psychology Group | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | |||

| Pretest | 41.05 ± 4.15 | 41.15 ± 3.39 | 39.20 ± 3.25 |

| Posttest | 28.06 ± 3.17 | 33.80 ± 3.94 | 40.50 ± 3.72 |

| Follow-up | 26.40 ± 4.17 | 32.40 ± 2.45 | 40.65 ± 4.40 |

| Motivational beliefs | |||

| Pretest | 72.10 ± 5.12 | 73.10 ± 3.73 | 70.20 ± 8.56 |

| Posttest | 85.50 ± 5.09 | 80.65 ± 6.47 | 70.25 ± 5.59 |

| Follow-up | 80.00 ± 5.45 | 75.50 ± 7.52 | 68.95 ± 3.41 |

The Mean and Standard Deviation of Research Variables in Experimental and Control Groups

For the inferential data analysis, we tested the null hypothesis concerning parametric statistics and conducted an ANOVA with repeated measures. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed that the data were normally distributed. Levene's test indicated equal variance across the dependent variables. Mauchly's test was used to assess sphericity, revealing an inconsistency in the variance-covariance matrix. As a result, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom for interpreting F. The outcomes of the repeated measures ANOVA are detailed in Table 5.

| Variables and Source | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | ||||||

| Time | 1929.34 | 1.99 | 968.14 | 83.22 | 0.001 | 0.59 |

| Group | 2061.81 | 2 | 1030.91 | 59.51 | 0.001 | 0.68 |

| Time × Group | 1597.16 | 3.99 | 400.73 | 34.45 | 0.001 | 0.55 |

| Motivational beliefs | ||||||

| Time | 1479.34 | 1.64 | 902.22 | 19.53 | 0.001 | 0.25 |

| Group | 2797.74 | 2 | 1398.87 | 30.32 | 0.001 | 0.52 |

| Time × Group | 952.39 | 3.28 | 290.42 | 6.25 | 0.001 | 0.18 |

Repeated Measurement Results for the Effects of Time, Group, and the Interaction of Time and Group

The results showed a significant effect of time on both psychological distress and motivational beliefs (P < 0.001). Specifically, students grieving the death of a parent demonstrated significant changes in psychological distress and motivational beliefs across the pretest, posttest, and follow-up evaluations. Moreover, the analysis of the groups indicated significant differences in scores for psychological distress and motivational beliefs between the positive psychology group, the ACT group, and the control group (P < 0.001). The interaction between time and group also revealed significant differences in scores for psychological distress and motivational beliefs across the pretest, posttest, and follow-up periods for the positive psychology group, the ACT group, and the control group (P < 0.001) (Table 5).

To further examine these differences, the Bonferroni post hoc test was performed, with the findings summarized in Table 6. Significant differences in scores for psychological distress and motivational beliefs were observed among the three groups at the pretest, posttest, and follow-up stages. These results underscore a significant difference in the effects of positive psychology training and ACT on psychological distress and motivational beliefs among students who have lost a parent.

| Variables and Groups | Mean Difference | Standard Error | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | |||

| Control-Positive psychology | 12.45 | 1.15 | 0.001 |

| Control-acceptance and commitment therapy | 6.70 | 1.15 | 0.001 |

| Positive psychology - acceptance and commitment therapy | -5.75 | 1.15 | 0.001 |

| Motivational beliefs | |||

| Control-Positive psychology | -15.25 | 2.28 | 0.001 |

| Control-acceptance and commitment therapy | -10.40 | 2.28 | 0.001 |

| Positive psychology-acceptance and commitment therapy | 4.85 | 2.28 | 0.012 |

Results of Pairwise Comparison of the Psychological Well-Being Across Time Series

5. Discussion

The main goal of this study was to explore the effects of positive psychology training and ACT on alleviating psychological distress and boosting motivational beliefs among students who have lost a parent. Both interventions, positive psychology training, and ACT, were effective in decreasing psychological distress among female secondary school students grieving over a parent's death. Notably, positive psychology training was found to be more effective than ACT in reducing psychological distress within this specific demographic. These outcomes align with findings from Ryff (33). Lorenz et al. (18) emphasized that positive psychology is based on the belief that individuals have a natural tendency towards growth, flourishing, and the pursuit of happiness, which helps combat feelings of worry, sadness, and anxiety. Positive psychology interventions have been successful in mitigating psychological trauma and enhancing happiness among students who have experienced parental loss by promoting a sense of purpose. These interventions include therapeutic strategies and deliberate activities designed to foster positive emotions, behaviors, and cognitive attitudes, thereby improving students' well-being and diminishing depression symptoms. Positive psychology focuses on recognizing and cultivating strengths, enhancing talents, and encouraging positive emotions and a meaningful life. As a result, it acts as a safeguard against behavioral issues, such as risky behaviors. Lorenz et al. (18) contend that the primary goals of positive psychology include achieving well-being, life satisfaction, and happiness. According to this perspective, an increase in positive emotions is closely linked with greater commitment, purpose, life satisfaction, and mental health, which support personal growth, self-enhancement, and improved mental health. Hence, positive psychology intervention programs are designed to increase life satisfaction, happiness, overall well-being, and mental health outcomes. In essence, life satisfaction, happiness, well-being, and mental health stand as critical factors in the observed reduction of psychological distress (stress, anxiety, and depression) through positive psychology training.

The use of ACT was effective in reducing psychological distress, corroborating findings reported by Prudenzi et al. (34). This effectiveness can be attributed to the fact that acceptance and commitment foster a nonjudgmental, balanced awareness, allowing individuals to recognize and accept their emotions and physical sensations as they occur (25). Therefore, teaching students who have endured the loss of a parent ACT techniques helps them to acknowledge and accept their psychological states and symptoms, diminishing their excessive preoccupation and emotional responses to issues related to the loss. This approach improves their adaptability. The ACT protocol included instructions on psychological flexibility, acceptance, mindfulness, and cognitive defusion. Cognitive defusion enables those dealing with the loss of a parent to objectively view their challenges and more openly communicate their distress, thus gaining a clearer comprehension of their core values and how to enact these values into specific actions (28). Additionally, increasing psychological awareness aids in making informed evaluations of their situations and challenges associated with parental loss, as mindfulness techniques in ACT provide new insights on mental events, allowing individuals to see their psychological experiences as temporary rather than inherent traits. High levels of experiential avoidance are often associated with reduced positive emotions, lower life satisfaction, and a sense of existential void. In contrast, ACT reduces experiential avoidance, promoting greater acceptance, which leads to outcomes like improved life satisfaction and reduced psychological distress.

The superior effectiveness of positive psychology over ACT in female students grieving the loss of a parent can be explained by the integration of positive psychology principles with spiritual beliefs. This synergy empowers students to leverage both positive psychological and religious strengths, thereby alleviating their psychological distress. Positive psychology fortifies their spiritual resilience, enhancing faith and adherence to religious tenets, thus helping them to cope better and reconcile with divine will. In summary, the amalgamation of positive psychology principles and religious values offers significant support to these students, reducing their psychological distress.

The findings further showed that both positive psychology training and ACT were effective in enhancing the motivational beliefs of female students who had experienced the loss of a parent, with positive psychology proving more effective than ACT. This outcome aligns with the research conducted by Corbu et al. (35). Delving into these results, positive psychology training is seen to aid students in boosting their self-confidence and skills, aligning their ambitions and motivations with their personal and ethical values. Such alignment contributes to increased self-efficacy. When combined with spiritual and moral beliefs, positive psychology can guide the choice of internal goals and values (19). It also helps students handle academic anxiety and diminish its effects by strengthening their stress management capabilities and fostering mental calmness. The principles of positive psychology can induce feelings of peace and faith in a higher power amidst academic challenges, ultimately boosting motivational skills, including goal-setting, resilience, self-confidence, stress management, and determination. These skills enable students to achieve their personal and spiritual goals, suggesting that integrating spirituality and psychology in life can enhance student motivation.

Additionally, the study found ACT to be beneficial in improving motivational beliefs among students grieving the loss of a parent, echoing findings from Fang and Ding (36). ACT is posited to increase self-efficacy by providing individuals with the tools to face challenges and accept negative experiences, thereby equipping students with the confidence to deal with difficult academic situations and learn from adverse experiences. Moreover, ACT encourages the development of a closer relationship with one's core values, guiding individuals in setting goals and motivations based on their internal and personal principles. Students who forge a strong connection with these values show increased motivation and align their educational efforts with their fundamental beliefs. By improving skills in managing stress and anxiety, ACT enhances academic motivation among students.

Regarding the superior effectiveness of positive psychology training over ACT in enhancing motivational beliefs among female students who have experienced the loss of a parent, it is proposed that religious principles and beliefs act as sources of hope and strength for these individuals. Approaching positive psychology with a religious perspective allows students to draw upon spiritual doctrines to boost their motivation and resilience in facing the distress and sadness of their loss. This training enables students to understand religious teachings about death and apply them in coping and adapting to such situations. This approach potentially enhances motivational beliefs that focus on divine providence and trust in a higher power.

This study focused on female secondary school students in Ahvaz, Iran, who were grieving the loss of a parent. The applicability of the study's findings might be limited to students experiencing parental loss within similar cultural or socio-economic settings, as the sample was somewhat uniform in terms of demographic attributes. The small sample size might also restrict the generalizability of the results to a wider population. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported measures for evaluating psychological distress and motivational beliefs could introduce response bias and subjectivity into the findings.

5.1. Conclusions

Both positive psychology training and ACT were found effective in improving motivational beliefs and reducing psychological distress among female secondary school students dealing with bereavement due to a parent's death. Moreover, positive psychology training showed greater effectiveness than ACT. Therefore, it is recommended that interventions based on positive psychology, incorporating spiritual values, be developed and offered to students facing such challenges. The amalgamation of positive psychology principles with spiritual beliefs could be a powerful approach to enhancing the psychological well-being of students navigating grief after losing a parent.