1. Background

The main causes of death in Iran have been identified as cardiovascular disease (CVD) (17.8%), motor vehicle collisions (MVC) (11.4%), and cancers (6.4%) (1). Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of cardiovascular deaths, while MVC-related mortality is predominantly due to head traumas and brain hemorrhages (2, 3). Although the most fatal malignancies, such as lung, prostate, and gastrointestinal cancers, progress slowly (4, 5), the other two leading causes of death—CVD and MVC—can occur suddenly without preceding events. This highlights the critical importance of prehospital care and the prompt provision of emergency medical services (6-9). One of the key factors affecting outcomes in these conditions is the time interval between the event and the initiation of treatment, particularly in CAD-related deaths (9-11). Given the rising rate of CVD-related deaths in Iran, identifying and addressing the causes of delays in initiating treatment for CVD and CAD would lead to a reduction in mortality and an improvement in the public health system's performance (12). This would also result in a reduction of the budget allocated to care for patients with chronic complications of CVD, freeing up resources for other health issues.

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is the leading cause of death in many parts of the world, with an even greater impact on specific populations, such as those with diabetes (13, 14). The severity of this condition varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic partial atherosclerosis to fatal large coronary thrombosis (15, 16). Myocardial function depends on the balance between the heart's oxygen supply and the cardiac muscle's demand; when oxygen supply is compromised, it leads to ischemia (1). The most severe and fatal form of this imbalance is ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI), which results from a complete or substantial reduction in oxygen delivery to the myocardium, causing acute ischemia. Rapid reperfusion through primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the cornerstone of acute STEMI treatment. The principle "time is muscle" emphasizes the urgency of preventing the progression of myocardial damage by ensuring timely revascularization of the affected coronary artery. This intervention reduces the risk of infarction, chronic heart failure, and mortality (17-21).

The key metric for determining the timing of PPCI is the time-to-treatment (TIT), which represents the duration from symptom onset to the initiation of reperfusion. Minimizing this duration is critical to prevent the extension of ischemia, underscoring the need for an efficient healthcare system to ensure rapid intervention (22). However, achieving timely revascularization in STEMI faces two main challenges: Patient delays (from symptom onset to initial medical contact) and system delays (the time interval from entering the emergency department to initiating PPCI). Efforts to reduce these delays have primarily focused on system delays, as they are more identifiable and modifiable than patient delays (23). Various strategies have been implemented to reduce system delays, including public education, training healthcare professionals to recognize STEMI, expedited activation of the catheterization laboratory, the use of prehospital triage to prioritize PPCI, minimizing transport time by bypassing the emergency department, and directly transferring patients to the catheterization laboratory (17, 24-27). Patient-related delays are influenced by factors such as socioeconomic status, gender, education, marital status, family history of heart disease, place of residence, and access to emergency services (27-29). However, there is no consensus on all these factors, and region-specific characteristics may also play a significant role in determining reperfusion timing.

2. Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the prehospital predictors of PPCI delay in STEMI patients and their impact on patient outcomes.

3. Methods

The present study, approved by the ethics committee of Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran (IR.AJUMS.REC.1395.1340), employed a prospective design to assess 584 suspected STEMI patients who visited the emergency rooms of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Ahvaz, Iran. Inclusion criteria required a definite diagnosis of STEMI by a cardiologist, with criteria including ST elevation of at least 1 mm in two or more contiguous leads on the initial electrocardiogram (ECG) or the presence of new presumed Q waves (19), the development of acute STEMI outside the hospital, and knowledge of the timing of symptom onset. Exclusion criteria included patients with spontaneous thrombolysis (chest pain relief and resolution of STEMI without pharmacological thrombolysis), a history of cardiac surgery, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke, and presentation 12 hours after symptom onset. Patients who could not recall the time of pain onset were also excluded from the study. Among the initial cohort, 394 patients met the eligibility criteria, while 190 patients were excluded. All participants or their next of kin provided written informed consent.

The study evaluated various time intervals: Patient delay, defined as the time from symptom onset to calling emergency medical service (EMS) or transport to the hospital; prehospital system delay, represented by the duration from EMS call to ambulance arrival and transport to the PPCI-capable hospital (EMS call-to-door time); and hospital delay, defined as the time from hospital arrival to revascularization (door-to-balloon time). The cumulative delay, considered as PPCI delay, comprised the sum of patient, prehospital system, and hospital delays. Patients were divided into two groups based on the time from symptom onset to PPCI: Those with ≤ 90 minutes were categorized as the on-time PPCI group, and those with > 90 minutes were classified as the delayed group.

3.1. Data Collection

Patient data were collected by a researcher, including demographic and clinical information such as age, gender, history of diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, hypertension (HTN), family history of heart disease, education level, marital status, Body Mass Index (BMI), presence of a caregiver at home, place of residence (urban or rural), and socioeconomic status. Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings were also recorded, including the type of ECG changes, the onset time of symptoms (pain or its equivalents), the admission time to the cardiology emergency unit, and the time of PPCI initiation. Patient outcomes tracked during the study included mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) or coronary care unit (CCU) admission, discharge, and the occurrence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) during the first year after PCI.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using Stata software version 17. Qualitative variables were reported as frequency and percentage, while quantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of continuous variables. Univariate analysis was conducted to compare findings between the groups with and without PPCI delay. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to identify predictors of PPCI delay. A significance level of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

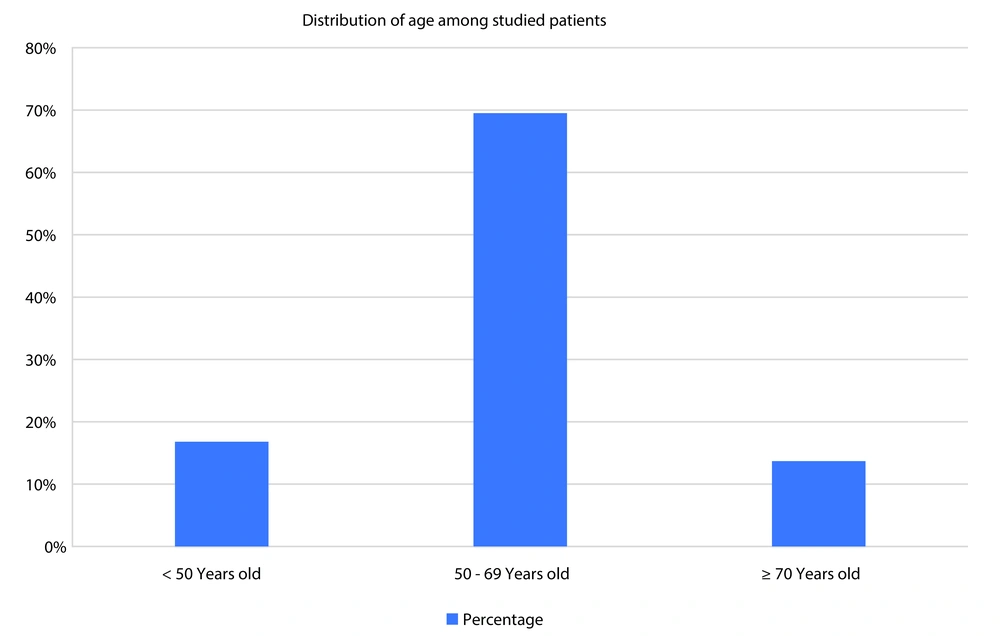

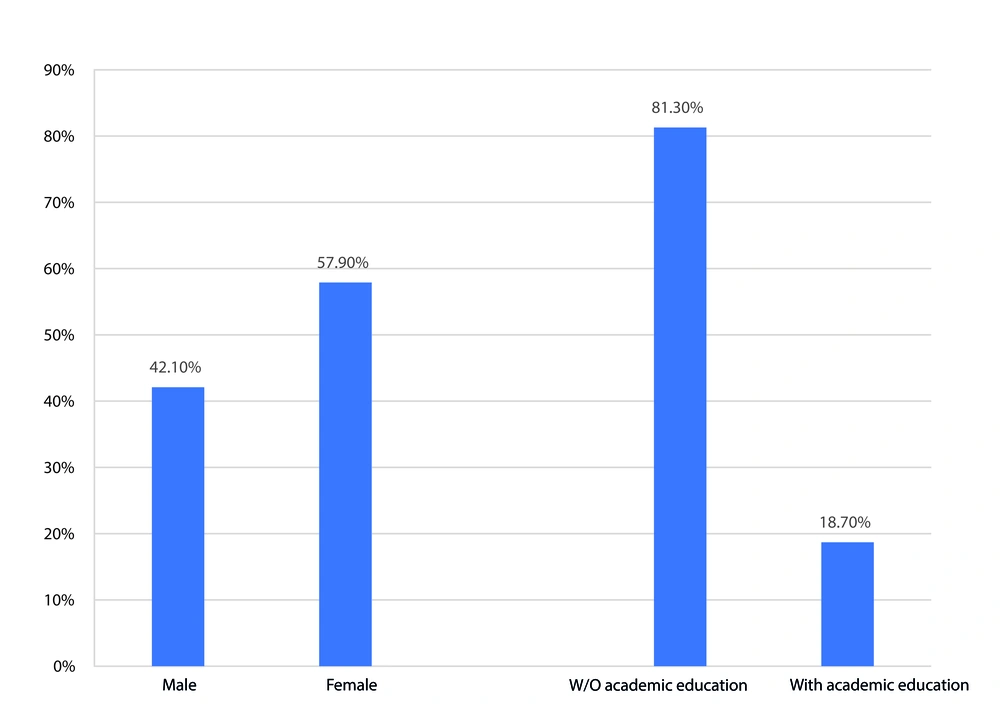

A total of 394 patients with a mean age of 63.68 ± 10.20 years, ranging from 36 to 88, were included in this study (Figure 1). Among them, 214 (57.9%) were female, 286 (72.3%) had an education level below a high school diploma, and 94 (23.9%) were living in rural areas at the time of their STEMI. The socioeconomic status of 315 (79.9%) patients was categorized as medium to low. Additionally, 104 (26.4%) patients had diabetes. Further demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | 394 STEMI Patients |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 63.68 ± 10.2 |

| < 50 | 66 (16.8) |

| 50 - 70 | 274 (69.5) |

| > 70 | 54 (13.7) |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 3.1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 180 (42.1) |

| Female | 214 (57.9) |

| Educational level | |

| Illiterate | 98 (24.5) |

| < Lower than academic level | 182 (46.6) |

| > Academic level | 114 (28.9) |

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 92 (23.4) |

| No | 302 (76.6) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Low | 158 (40.1) |

| Moderate | 161 (40.9) |

| High | 75 (19) |

| Positive family history of CVD | 52 (13.2) |

| Type of comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 104 (26.4) |

| HTN | 118 (29.9) |

| Dyslipidemia | 58 (14.7) |

| Visiting hours during the day and night | |

| 6 AM to 12 PM | 92 (23.4) |

| 12 PM to 6 PM | 90 (22.8) |

| 6 PM to 12 AM | 90 (22.8) |

| 12 AM to 6 AM | 122 (31.5) |

| Mode of transport to the emergency room | |

| Private device | 280 (71.6) |

| Ambulance | 114 (28.4) |

| Having a caregiver or living with children | |

| Yes | 114 (28.9) |

| No | 280 (71.1) |

| Previous history of heart disease (Except MI) | |

| Yes | 40 (10.16) |

| No | 354 (89.84) |

| Family history of cardiac disease | |

| Yes | 52 (14.2) |

| No | 342 (86.8) |

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients a

For the purpose of classification, those living in cities and towns were classified as urban area residents, while those living in other territories were classified as rural area residents. The socioeconomic classification was based on the average annual income of Iranian families. Patients within the top 50th percentile were categorized as belonging to high socioeconomic classes, while those in the lower percentiles were classified as belonging to lower socioeconomic classes.

The average duration from symptom onset to emergency department (ED) arrival was 94.50 ± 56.6 minutes, with an average of 39.2 ± 33.2 minutes from ED admission to PPCI initiation. The overall timeframe from symptom onset to the performance of PPCI averaged 124.2 ± 50.1 minutes. Notably, delayed PPCI, defined as a duration of ≥ 90 minutes from symptom onset, was observed in 192 patients.

4.2. Univariate Analysis

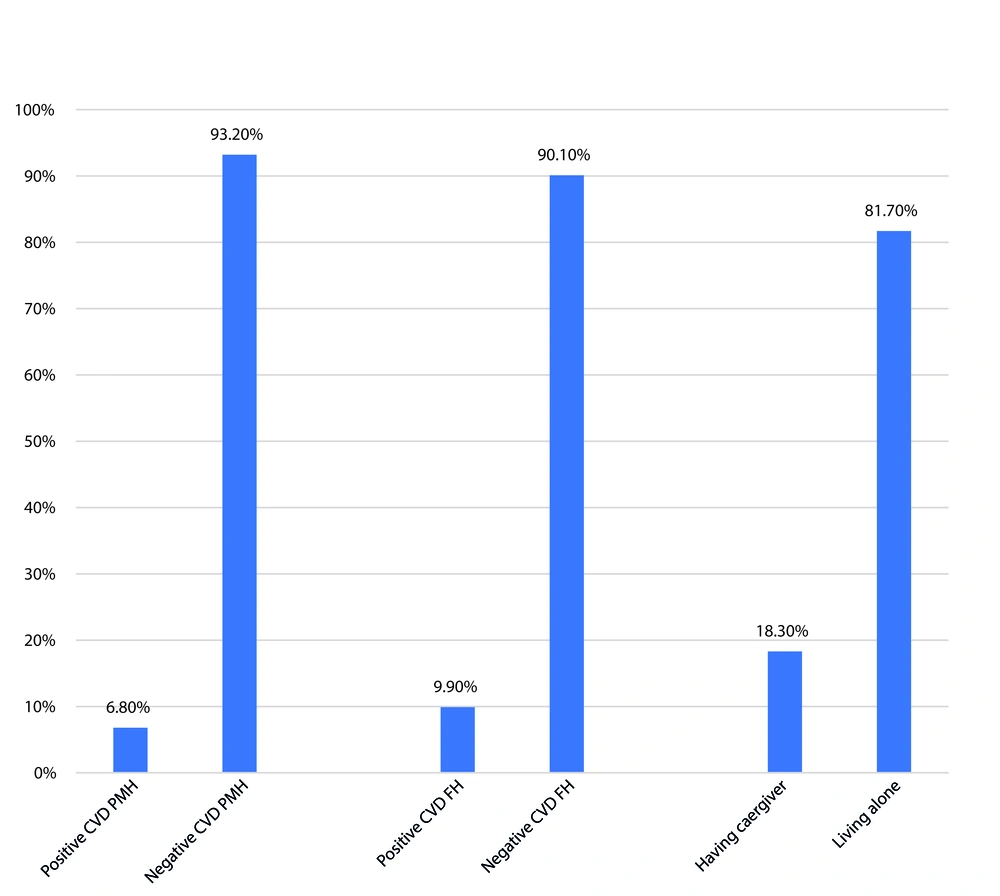

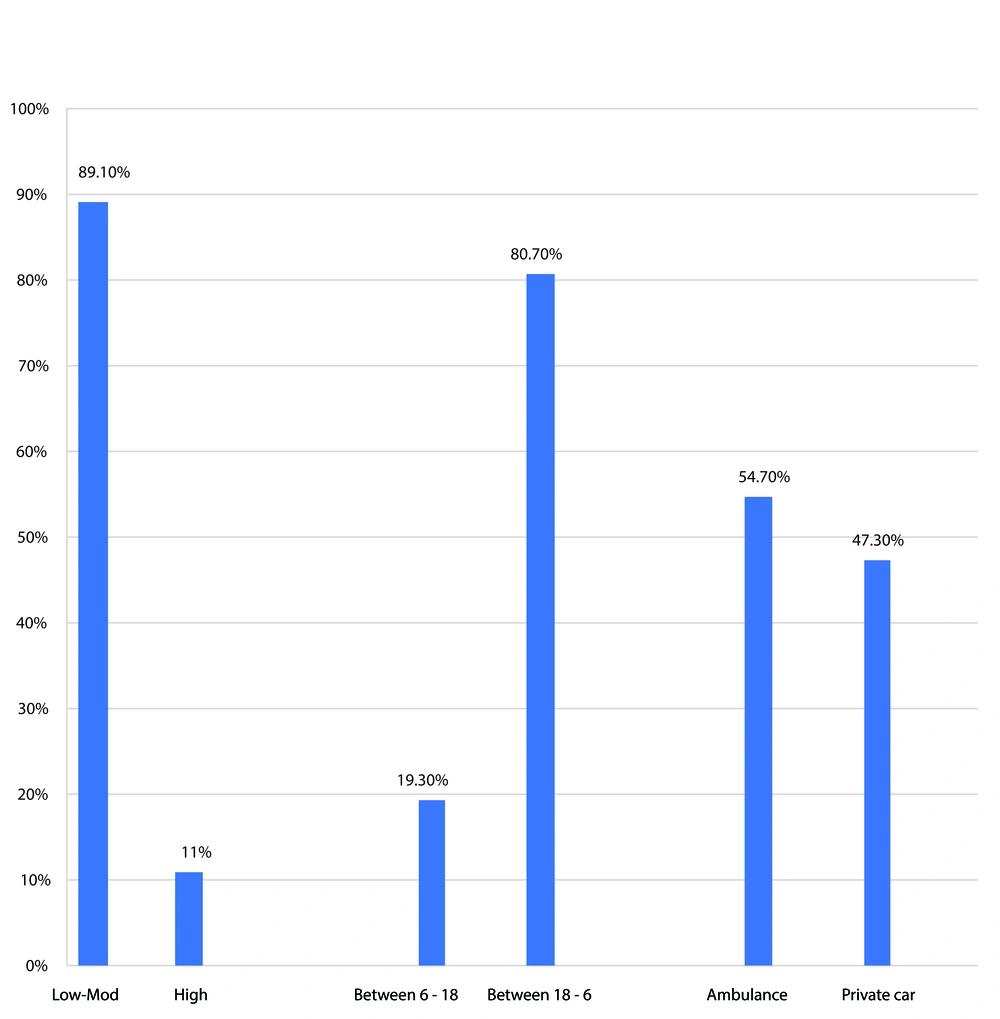

Univariate analysis revealed that the mean time from symptom onset to PPCI was significantly shorter in patients who were transported to the hospital by private means compared to those transported by ambulance (108 ± 50.2 minutes vs. 155.2 ± 54.6 minutes, P-value: < 0.01). Additionally, among patients with PPCI delay, there was a significantly higher frequency of women and those with lower education levels (not completing high school) (Figure 2). Delayed PCI was also significantly more common in patients without a history of CVD, without a family history of CVD, and in those living alone (Figure 3). Rural residents, individuals with lower socioeconomic status, patients who experienced symptom onset between 18:00 and 06:00, and those living more than 60 km from the nearest center equipped for PPCI had a significantly higher risk of delayed PPCI (Figure 4). No statistically significant association was found between PPCI delay and other factors such as age, history of smoking, and other comorbidities (Table 2).

Patients with low-moderate socioeconomic status, those who experienced the pain or arrived at the ED between 18 and 6, and those who used an ambulance car for transportation to the hospital had significantly more incidence of delayed percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in comparison with their counterpart group.

| Variables | PCI Delay | OR (95%CI) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With PCI Delay N = 192 | Without PCI Delay N = 202 | |||

| Age (y) | 62.58 ± 11.2 | 64.71 ± 9.9 | 0.99 (0.9, 1.08) | 0.56 |

| Gender | 0.001 | |||

| Male | 65 (33.9) | 115 (56.9) | Ref | |

| Female | 127 (66.1) | 87 (43.1) | 1.89 (1.12, 2.67) | |

| Educational level | 0.004 | |||

| < Lower than Academic Level | 156 (81.3) | 124 (61.4) | Ref | |

| > Academic Level | 36 (18.7) | 127 (38.6) | 0.66 (0.45, 0.87) | |

| Smoking | 0.62 | |||

| Yes | 42 (21.9) | 50 (24.8) | Ref | |

| No | 150 (78.1) | 152 (75.2) | 0.98 (0.8, 1.18) | |

| Family history | 0.014 | |||

| Positive | 19 (9.9) | 33 (16.3) | Ref | |

| Negative | 173 (90.1) | 169 (83.7) | 1.45 (1.1, 1.81) | |

| Previous history of heart diseases | 0.009 | |||

| Positive | 13 (6.8) | 27 (13.4) | Ref | |

| Negative | 179 (93.2) | 175 (86.6) | 1.61 (1.11,2.12) | |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Low | 98 (40.1) | 60 (29.7) | Ref | |

| Moderate | 73 (49) | 88 (43.6) | 0.79 (0.69,0.9) | 0.039 |

| High | 21 (10.9) | 54 (26.7) | 0.51 (0.35,0.67) | 0.006 |

| Comorbidities | 0.23 | |||

| Yes | 58 (30.2) | 59 (29.2) | Ref | |

| No | ||||

| Visiting hours during the day and night (pm) | 0.019 | |||

| 6:00 to 18:00 | 37 (19.3) | 75 (37.1) | Ref | |

| 18:00 to 5:59 | 155 (80.7) | 127 (62.9) | 1.91 (1.11, 2.72) | |

| Transport to the emergency room | 0.029 | |||

| Private device | 105 (54.7) | 175 (86.6%) | Ref | |

| Ambulance | 87 (45.3) | 27 (13.4) | 1.67 (1.06, 2.19) | |

| Having a caregiver or living with children | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 35 (18.3) | 79 (39.1) | Ref | |

| No | 157 (81.7) | 123 (60.9) | 2.14 (1.15, 3.16) | |

Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Delayed Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PPCI) a

4.3. Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate analysis revealed that several factors were significantly associated with a higher risk of delayed PCI. Being female (OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.08 - 2.01, P-value: < 0.01), having no past medical history of CVD (OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.09 - 1.90, P-value: < 0.01), no family history of CVD (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.04 - 1.53, P-value: 0.03), a lower education level (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.05 - 1.84, P-value: 0.01), symptom onset between 18:00 and 06:00 (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.10 - 2.06, P-value: 0.01), and transport by ambulance versus private vehicle (OR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.07-2.08, P-value: < 0.01) were all significantly associated with delayed PCI. Conversely, higher socioeconomic status (OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.51 - 0.86, P-value: 0.023) and having a caregiver at home (OR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.32 - 0.72, P-value: < 0.01) were significantly associated with a lower risk of delayed PPCI (Table 3).

| Variables | OR Adjusted | 95%CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female vs. male) | 1.59 | 1.08 - 2.1 | 0.001 |

| Negative family history | 1.28 | 1.04 - 1.53 | 0.032 |

| Negative previous history of heart diseases | 1.49 | 1.09 - 1.90 | 0.024 |

| Educational (< academic level vs. ≥ academic level) | 1.44 | 1.05 - 1.84 | 0.012 |

| Socioeconomic status (high Vs. moderate or low) | 0.68 | 0.51-0.86 | 0.023 |

| Time of onset of symptoms (18:00 to 5:59 Vs. 6:00 to 18:00) | 1.58 | 1.10-2.06 | 0.014 |

| Using an ambulance vs. private vehicle | 1.57 | 1.07-20.8 | 0.006 |

| Having a caregiver or living with children (yes Vs. no) | 0.52 | 0.32-0.72 | 0.001 |

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Delayed-PPCI

5. Discussion

One of the most important concerns in providing treatment for patients with CVD and cancer has been ensuring equality and addressing disparities among various socioeconomic, ethnic, gender, and racial groups. Studies have shown that lower income, lower socioeconomic status, and rural residency are associated with a higher incidence of CVD and increased mortality rates due to these diseases (30-33). Additionally, evidence suggests that appropriate prehospital logistics can reduce delays in treating STEMI and improve overall outcomes for patients with this condition (34).

According to the results of this study, multivariate analysis identified several factors significantly associated with an increased incidence of delayed PPCI, including rural residency, lower education levels (below the academic level), absence of a family history or personal history of CVD, female gender, and symptom onset between 18:00 and 06:00. Conversely, using a private vehicle for transportation instead of an ambulance, having a caregiver, and higher socioeconomic status were significantly associated with a reduced risk of delayed PPCI.

Achieving timely reperfusion of occluded coronary arteries through PPCI in STEMI patients leads to reduced morbidity and mortality rates. Minimizing delays in providing PPCI serves as a marker of high-quality health service delivery (17). In a study involving 1791 STEMI patients, the association between TIT and cardiovascular outcomes was evaluated, demonstrating that every half-hour delay in perfusion was associated with a 7.5% increase in mortality at one-year follow-up (35). Another study showed that every 30-minute delay in reperfusion (increased TIT) was associated with a 37% increase in transmural necrosis (36). Successful management of STEMI relies on several factors, including timely patient presentation, prompt physician diagnosis of STEMI, and early initiation of reperfusion therapy. Reducing PPCI delay depends on individual epidemiological characteristics, access to medical services, and geographic location, which can significantly impact morbidity and mortality rates (37).

This study aimed to evaluate predictors of PPCI delay in 394 STEMI patients, with an average age of 63. Beig et al. (38) examined treatment delays in 523 STEMI patients, with a mean age of 57, identifying rural residency and a negative family history of coronary artery disease as significant factors associated with PPCI delay. Other studies have shown that mortality rates and severe cardiac outcomes were higher in populations and families without a history of heart disease due to less awareness of the condition (39, 40). This is consistent with the results of our study, which showed that STEMI patients without a family or personal history of CVD were at a higher risk of delayed PPCI compared to those with such histories. Similarly, CGA Nielsen et al. found that being female and experiencing symptoms between 22:00 and 06:00 were significantly associated with higher patient-related delays, possibly due to reduced access to transportation, especially in rural areas (41). Additionally, the reduced availability of cardiologists during nighttime hours, particularly in small towns, might worsen this condition.

The results of studies evaluating PPCI outcomes between genders have been mixed. While some studies concluded that there was no significant difference in post-PCI clinical outcomes and in-hospital stay between genders (42), a study by Pilgrim T. et al. found disparities in the provision of primary PCI and the time between symptom onset and PPCI based on age and gender. The study showed that both genders aged ≥ 65 years, compared to younger patients, and women younger than 65, compared to men in the same age group, had a higher risk of delayed PPCI (43). This finding aligns with our conclusion, showing a higher risk of delayed PCI in the female group. Furthermore, a survey conducted by Meyer et al. (27) revealed that women experienced greater PPCI delays than men, potentially due to longer total ischemic time and delays in seeking medical attention. Unlike men, female patients' delays in seeking treatment are not necessarily associated with persistent chest discomfort, indicating that women with STEMI are less likely to recognize their symptoms as requiring immediate action.

Fournier et al. (44) evaluated the effect of socioeconomic status on PPCI delay, management, and outcomes in STEMI patients, finding that low socioeconomic status and education level were significantly associated with increased PPCI delay, which supports the findings of our study. Similarly, Stehli et al. (45) identified gender as significantly associated with excessive patient, prehospital system, and hospital delays, with women experiencing longer delays compared to men. The study found that prehospital system and hospital delays resulted in a 10-minute excess adjusted delay in women compared to men.

Given the elevated risk of mortality and MACE in patients who experience delays in primary reperfusion, it is recommended that the associated factors be evaluated and addressed urgently. This is especially important in financially deprived regions, such as the province evaluated in this study, where addressing logistical obstacles in prehospital settings can lead to significant reductions in morbidity and mortality related to STEMI.

To better understand the factors predicting PPCI delay in Iran, a more comprehensive study with a larger sample size would be necessary. This study covered the main tertiary teaching hospitals in Ahvaz, which are the primary referral centers for STEMI patients, providing a valid conclusion as it involved a wide range of the population undergoing PPCI for STEMI. However, the study had limitations that should be noted. The time of onset of STEMI symptoms, a crucial factor, was recorded based on self-reporting by the patient or their family/caregivers, which may have affected the accuracy of the study. Additionally, this study was conducted on a specific population in a province in southwestern Iran, which may limit the generalizability of its findings.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study showed that living alone, having a negative past medical history (PMH) and family history (FH) of CVD, living in rural areas distant from interventional cardiology centers, transportation by ambulance, lower education level, female gender, lower socioeconomic status, and the onset of pain between 18:00 and 06:00 were significantly correlated with a higher incidence of delayed PPCI.