1. Background

Low back pain (LBP) and neck pain (NP) are of the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorders due to technological improvement and sedentary life style in developed and developing countries, in a way that 60-80% of people have experienced LBP at least once in their lives (1). Although LBP is often self-improving, half of the affected subjects have history of prolong or repetitive LBP (2). This group of patients is accounted for 80% of LBP-related cost (3). In Iran, the prevalence of LBP in general population, employees, students and pregnant women is different from 14.4% to 84.1% (4). Studies have shown that the prevalence of LBP and NP is high among hospital nurses; thus, they are considerable subjects for investigation (5, 6). Mohseni et al. reported the prevalence of LBP and NP among nurses of north of Iran to be more than 50% (7). Mehrdad and his colleagues indicated that the prevalence of LBP and NP was 73.2% and 48.6%, respectively (8). The most important reasons reported for vertebral spine and joints disorders included: awkward position of the joints during resting or working, lack of awareness about physical health during daily activities such as working for a long time uninterruptedly or wrong habits and awkward postures, muscle imbalance, neglecting treatment of such disorders, and poor condition of work environment such as inappropriate instruments (9). Several studies have shown the related risk factors for LBP and NP; but, there is controversy on relation of posture with LBP and NP (10, 11), since most of the studies have been performed among industrial populations or specific health personnel, in addition to poor methodologies due to assessments by questionnaires. Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), especially LBP, result in high prevalence of drug consumptions, work absenteeism, disability, and psychosocial problems (12-20). Physical factors such as heavy lifting, repetitive tasks and staying in a static position for a long time, as well as psychological factors like high level of stress, depression, self-satisfaction and social support are important in job-related MSD (21). The high prevalence of MSD imposes direct and indirect cost for both patients and the society (22, 23). Recognition of the related risk factors and planning for their prevention and reduction are necessary. Previous studies have shown that the cost of LBP and NP was about 761 million dollars; however, the cost of leaves of health personnel was nine times more than the direct cost of MSD treatment (24). In our society, more studies are needed on effectiveness of these strategies in different populations. Since prevention is a critical matter, ergonomic and educational plans for employees have been evaluated in several studies in different countries (25-30). Nurses are in exposure of MSDs (5, 6), because they have to stand or keep a wrong position for a long time (31); in addition, they are under lots of stresses (32) because of work shifts, working with patients, facing deaths, and being responsible for people's health (33, 34). In Iran, there are few evidences in this area, performed in certain populations (23), which indicate that neck and upper limb injuries are prevalent in females, while back and lower limb injuries are prevalent among males. Since job activities are performed in different postures, finding out how these postures influence the body is important in controlling and decreasing MSD. Therefore, improving the knowledge and health of people by modifying their routine activities and providing enough education about increasing factors of MSD is important in controlling MSD and decreasing the respective costs. Investigations have revealed the low level of knowledge about ergonomics among hospital personnel in Iran (35-37).

2. Objectives

The aims of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of ergonomic training on pain intensity, posture, range of motion (ROM), function, cost of treatment, and sick leaves in patients with LBP and NP, manage their related costs, and assess the association of risk factors related to LBP and NP such as poor posture and wrong habits with sick leaves and costs of treatment in a population of female hospital personnel.

3. Patients and Methods

In this quasi-experimental study, with a power of 80% and an alpha coefficient of 0.05, 49 patients were included from all female hospital personnel by consecutive sampling, considering equal ratios for different positions (ward, paraclinic and office). We studied females because they were more accessible. The inclusion criteria were age range of 19-50 years old and history of LBP or NP and the exclusion criteria included history of any serious psychological or systemic disease, acute or infectious disease, epilepsy, cancer, osteoporosis, spinal injury, and any surgery during the last year (38). In addition, if any of the subjects rejected to continue the study, was unable to complete it, or participated in any other program such as exercise or treatment, she/he was excluded. After inviting eligible subjects and obtaining their informed consents, demographic data as well as the information about LBP and NP, including pain duration and nature, physician referral, using diagnosis and treatment procedures and sick leaves were collected through a questionnaire; visual analog scale (39) and Nordic questionnaire (40) were used to measure pain intensity and prevalence of MSDs, respectively. Then the subjects were evaluated by a physiotherapist physically and their postural status, back and neck range of motion (ROM), and function were assessed. For postural evaluation, a net-like mirror and a plumb line were used and the posture was assessed from anterior, posterior and lateral position in a standing attitude; then, according to the number of faulty postures compared with the standard posture in the standing position, the score was graded as weak, moderate, good, and normal. ROM and function were measured using the Likert scale (normal, good, moderate, a few limited, and completely limited). The back tests included back to wall, press-up, Ober test, Ely test, Thomas test, slight leg rising, leg drop test, knee roll, and press up. The score of back test was based on the number of successful tests, reported as weak, moderate, good, and normal. Finally, the risk of MSD was calculated based on the score of these tests, according to its standard scale (41). In this way, risk scores 0-6 were considered as low risk, 7-10 moderate risk, 11-18 high risk, and more than 19 very high risk. The intervention included face-to-face and group education considering the importance of ergonomic and postural awareness as well as the methods of controlling the related risk factors; these included modifying the posture and setting changes of the environment and instruments, with emphasis on keeping a good posture during work, changing their posture during work, and suitable exercises ordered by the physiotherapist according to their problems. They were followed weekly for six months. In addition, face-to-face education for postural modification and the way of performing daily activities regarding their condition were afforded after evaluation by a physiotherapist. All the examinations were repeated after six months. The number of sick leaves and the related costs, including the costs of treatment, diagnosis and work absence, were calculated for the last 10 months before the study as well as the 10 months after beginning the study. Data was analyzed by SPSS 15 software. The results were reported in percentage of frequency, mean and standard deviation (SD). Paired t-test was used to compare the data before and after the intervention; linear regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between the variables and logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the influence of risk factors on LBP, NP, and sick leaves.

4. Results

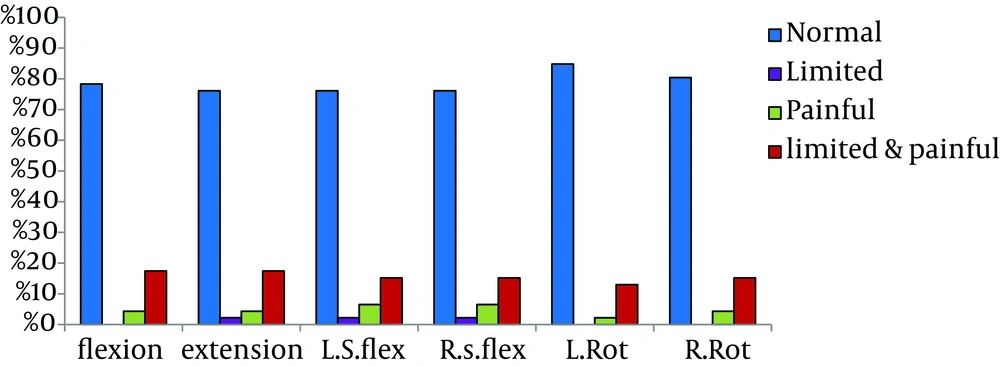

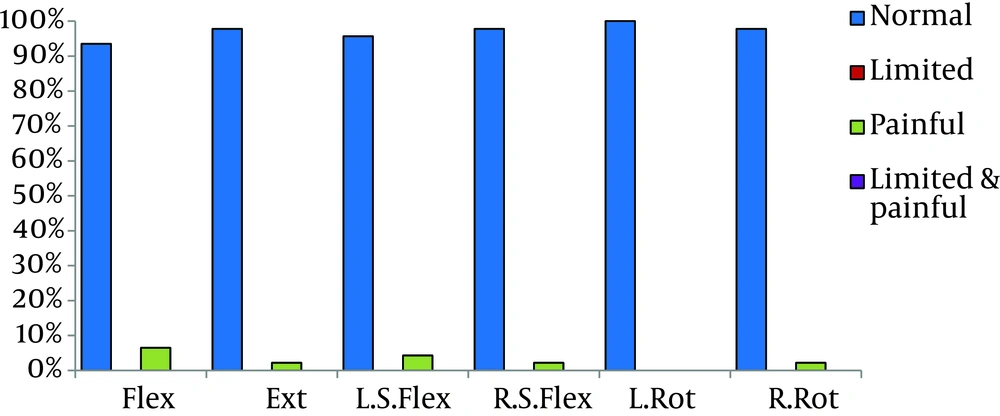

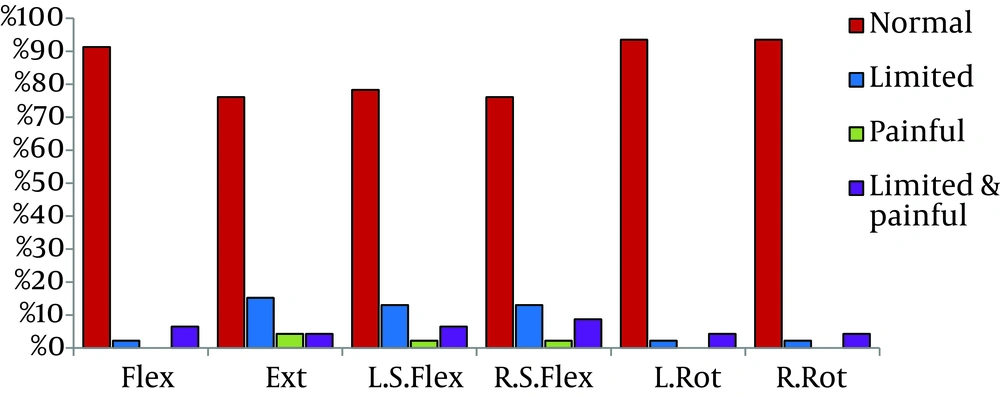

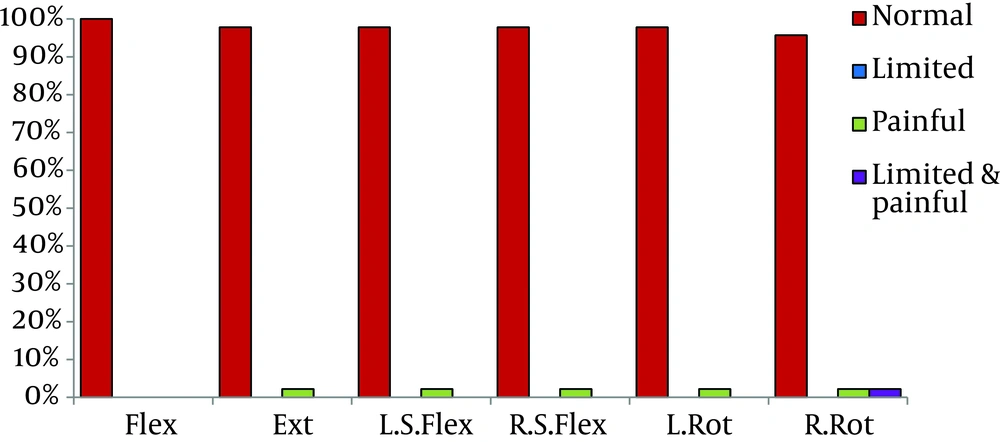

The main purpose of the current study was evaluating the influence of ergonomic training on pain, ROM, function, and costs related to LBP and NP. Demographic data of the studied population are presented in Table 1. The prevalence of LBP and NP was 87% and 45.7%, respectively. Repetitive tasks had the highest frequency among the related risk factors (67%). Figures 1 to 4 indicate the frequency of subjects based on ROM. The frequency of subjects with limited ROM decreased significantly after intervention. The score of functional statuses (walking, stair climbing, standing, job performance, and daily activities) increased significantly after the intervention (Table 2). Before the intervention, the means of back and posture scores were 1.41 ± 1.53 and 0.89 ± 1.08, respectively, which were good according to the scale; the mean of pain intensity was 6.70 ± 2.30 and the risk of MSD was 14.39 ± 3.50, which both were high, according to the scale. After the intervention, pain intensity (P = 0.000), scores of back (P = 0.000) and posture tests (P = 0.000), risk of MSD (P = 0.001), weight (P = 0.01), waist circumference (P = 0.003), body mass index (P = 0.01), and sick leaves (P = 0.001) decreased significantly (Table 4). The costs related to sick leaves (P = 0.001) and total costs of LBP and NP (P = 0.03) decreased significantly, but the reduction of treatment cost of LBP and NP was not significant (P = 0.098) (Table 3). Table 4 shows the frequency of related risk factors, which was higher for prolong standing, poor posture, and job stress. The number of sick leaves was related to pain intensity (P = 0.02) and having job stress (P = 0.02). The costs of treatments for LBP and NP were significantly related to the duration of LBP and NP (P = 0.037) and heavy lifting (P = 0.03) (Table 5).

| Variable | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Neck pain | 455.7 |

| Low back pain | 87 |

| Radicular pain | 56.5 |

| Work place | |

| Ward | 43.5 |

| Office | 23.9 |

| Laboratory | 21.7 |

| Emergency ward | 4.3 |

| Others | 6.6 |

| Cause of pain | |

| Falling | 13 |

| Heavy lifting | 6.5 |

| Repetitive tasks | 67 |

| Pattern of pain | |

| Morning | 17.4 |

| Evening | 15.4 |

| Night | 13 |

| During the day | 21.7 |

| Irregular | 32.5 |

| Increasing factors | |

| Sitting | 17.4 |

| Standing | 39 |

| Walking | 37.1 |

| Others | 6.5 |

| Treatment | |

| Nothing | 60.9 |

| Drug | 15.2 |

| Physiotherapy | 4.4 |

| Exercise | 8.7 |

| Rest | 8.7 |

| Others | 2.1 |

| Using corset | 6.5 |

| Work absence | 34.8 |

| Physician referral | 15.2 |

| Diagnosis process | 56.5 |

| Job | |

| Paraclinic personnel | 28.3 |

| Nurse | 45.7 |

| Regular staffer | 26.1 |

| Being married | 54.3 |

Baseline Characteristics of the Studied Populationa

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Good | Moderate | Weak | No function | mean ± SD | Normal | Good | Moderate | Weak | No function | Mean ± SD | |

| Dressing | 73.9 | 15.2 | 8.7 | 2.2 | 0 | 4.61 ± 0.75 | 73.9 | 17.4 | 8.7 | 0 | 0 | 4.65 ± 0.64a |

| Combing | 71.7 | 23.9 | 4.3 | 0 | 0 | 4.63 ± 0.71 | 78.3 | 17.4 | 4.3 | 0 | 0 | 4.74 ± 0.54a |

| Walking | 34.8 | 32.6 | 21.7 | 0 | 0 | 3.91 ± 1.01 | 63 | 23.9 | 8.7 | 4.3 | 0 | 4.46 ± 0.84a |

| Stair climbing | 28.3 | 15.2 | 21.7 | 32.6 | 2.2% | 3.35 ± 1.27 | 45.7 | 23.9 | 19.6 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 4.00 ± 1.16a |

| Bathing | 58.7 | 32.6 | 4.3% | 4.3 | 0% | 4.46 ± 0.78 | 67.4 | 23.9 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0 | 4.54 ± 0.78a |

| Toileting | 47.8 | 13 | 26.1 | 13 | 0% | 3.96 ± 1.13 | 60.9 | 21.7 | 13 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 4.37 ± 0.95a |

| Standing | 54.3 | 17.4 | 19.6 | 8.7 | 0 | 4.17 ± 1.05 | 67.4 | 26.1 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 0 | 4.52 ± 0.89a |

| Bending | 30.4 | 28.3 | 17.4 | 23.9 | 0 | 3.65 ± 1.16 | 63 | 19.6 | 10.9 | 6.5 | 0 | 4.39 ± 0.93a |

| Wearingshoes | 54.3 | 21.7 | 10.9 | 13 | 0 | 4.17 ± 1.08 | 63 | 21.7 | 10.9 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 441 ± 0.93a |

| Working | 19.6 | 45.7 | 23.9 | 10.9 | 0 | 3.74 ± 0.91 | 52.2 | 26.1 | 15.2 | 6.5 | 0 | 4.24 ± 0.95a |

| Daily activities | 28.3 | 37 | 17.4 | 17.4 | 0 | 3.76 ± 1.06 | 52.2 | 23.9 | 15.2 | 8.7 | 0 | 4.20 ± 1.00a |

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | 6.70 ± 2.30 | 2.02 ± 2.64 | 0.00 |

| Back and neck test | 1.41 ± 1.53 | 0.04 ± 0.51 | 0.00 |

| Posture score | 0.89 ± 1.08 | 0.07 ± 0.25 | 0.00 |

| Sick leaves, d | 1.93 ± 3.78 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.001 |

| Costs of treatment | 329422.2 ± 1237734.93 | 16666.67 ± 82574.28 | 0.098 |

| Costs related to sick leaves | 96739.13 ± 189854.38 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.001 |

| Total costs, Rials | 428311.1 ± 1259827.26 | 16666.67 ± 82574.28 | 0.034 |

| Weight, kg | 65.37 ± 16.08 | 63.86 ± 10.51 | 0.01 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 88.80 ± 11.00 | 85.74 ± 11.62 | 0.003 |

| Risk of MSD | 14.39 ± 3.50 | 12.54 ± 3.76 | 0.001 |

| Duration of LBP, mo | 19.67 ± 13.17 | - | - |

| Duration of NP, mo | 8.71 ± 3.59 | - | - |

| Age, y | 34.46 ± 5.36 | - | - |

Comparing the Variables Before and After the Interventiona

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Sometimes | Often | Never | Sometimes | Often | |

| Physical activity | 93.5 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 89.1 | 8.7 | 2.2 |

| Heavy activity and lifting | 52.2 | 41.3 | 6.5 | 52.2 | 41.3 | 6.5 |

| Prolong standing | 6.5 | 28.3 | 65.2 | 10.9 | 28.3 | 60.9 |

| Job stress | 2.2 | 17.4 | 80.4 | 4.3 | 23.9 | 71.7 |

| Prolong sitting | 23.9 | 52.2 | 23.9 | 21.7 | 60.9 | 17.4 |

| Repetitive movements | 23.9 | 60.9 | 15.2 | 26.1 | 60.9 | 13.0 |

| Bad positions | 4.3 | 45.7 | 50.0 | 8.7 | 54.3 | 37 |

| History of back or neck pain | 8.7 | 30.5 | 60.9 | 8.7 | 30.5 | 60.9 |

| Family history of joint disorders | 47.8 | 52.2 | 52.2 | 47.8 | 52.2 | 52.2 |

Frequency of Risk Factors Related to Back and Neck Paina

| Sick Leaves | Costs of Sick Leaves | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slop of Regression Line (Beta) | P Value | Slop of Regression Line (Beta) | P Value | |

| Pain intensity | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.43 |

| Back/neck test | -0.05 | 0.75 | -0.05 | 0.74 |

| Posture score | -0.15 | 0.41 | -0.16 | 0.37 |

| Body mass index | 0.05 | 0.73 | -0.02 | 0.89 |

| Duration of LBP | -0.07 | 0.66 | 0.35 | 0.037 |

| Risk of MSD | 0.08 | 0.60 | -0.27 | 0.09 |

| Heavy lifting | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.03 |

| Prolong standing | -0.22 | 0.39 | -0.03 | 0.90 |

| Prolong sitting | -0.17 | 0.44 | -0.31 | 0.15 |

| Repetitive movements | -0.20 | 0.36 | -0.30 | 0.13 |

| Bad positions | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.11 |

| Job stress | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.13 |

Association of Sick Leaves and its Cost With Pain Intensity; Scores of Back and Neck and Posture Testa

5. Discussion

Ergonomic training decreased the pain intensity, risk of MSD, and sick leaves significantly, but reduction of the related costs was not significant. This study was valuable according to clinical postural evaluation in comparison with some studies that used questionnaires for postural data. Obviously, clinical measurement provides more precise data than just filling questionnaires. The results of the present study showed that the subjects had a high risk of MSD, which was related to prolong sitting and standing, doing repetitive tasks, and wrong postures. These results were in accordance with other studies by Choobineh (23) and Mehrdad (8). Choobineh reported the prevalence of LBP and NP about 60.6% and 51%, respectively and Mehrdad reported the prevalence of LBP and NP about 73.2% and 48.76%, respectively, in nurses of operation room. The mean of pain intensity was higher in the study by Choobineh, probably due to high level of stress and different kinds of activities in nurses of operation room. Another factor describing the difference of pain intensity between our study and other studies can be the study population; we studied all hospital stuffs; but in the study by Choobineh, just the operation room nurses (with different duties) were studied. The relationship between risk factors of LBP and NP in our study was similar to that of the study by Choobineh, which included heavy lifting and repetitive tasks in his study. Smelly et al. showed that neck and shoulder pains are related to carrying patients in beds by nurses (42), while Smith and colleagues showed that psychological factors had the strongest role in MSD (43). This difference can be due to different activities of nurses as well as the level of help by assistants, patients and caregivers during heavy activities such as patients' carrying and bathing in these studies. According to the results of our study (Table 5), only 6.5% of our studied population had heavy activities and lifting during their work, while 65.2% of them regularly stood for long periods and 80.2% of them had job stress during work. Therefore, the risk factors are different in various populations even for a similar job and these differences should be considered in the preventive and controlling strategies for future. The prevalence of MSD was the highest for LBP and then for NP in most of the studies (22). In Our study, the prevalence of LBP was higher than NP. However, there was not any significant relationship between pain intensity and score of posture, which can be due to the good score of posture and the low mean age of this population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) stratification (44), people were divided to two groups based on their ages: < 45 and > 45 year old. Our studied population was under 45 years old (mean age: 43.5 ± 43.5). In this age, range of the postural disorders is not fixed yet. However, poor posture gradually appears through incorrect job positions and daily activities and habits. Therefore, according to high level of MSD risk factors and high risk of MSD in this population, postural disorders could increase in the future. In our study, most participants were nurses or office employees who had repetitive task during works. In different countries, psychological factors were related to MSD among nurses (6, 7, 23, 45-47); however, it was not in the scope of this study and only job stress was asked in the questionnaire, which was not related to pain intensity but was related to sick leaves.

Several studies investigated the effectiveness of different treatment protocols including education, ergonomic change in work sites, using auxiliary devises and help mates, relaxation and exercise for decreasing MSD, especially LBP in nurses (27, 48-50). Education toward correct daily and job activities as well as suitable physical activity is one the most important ways of improving the musculoskeletal function. (27, 48-51). In the present study, face-to-face and group education on MSD risk factors and how to encounter them through appropriate task performance and enough physical activity had remarkable influence on reduction of LBP and NP prevalence, sick leaves, risk of MSD, and costs of treatment. Nevertheless, such an intervention in other hospitals with premium treatment and diagnosis processes could be more cost-effective, because this study was performed in a hospital related to the social security organization with free treatment and diagnosis for the personnel and the calculated cost included out of hospital care costs. In a systematic review, Maher evaluated 13 randomized clinical trials on effects of different interventions in prevention of LBP and indicated that there is moderate evidence on effect of education in prevention of job-induced LBP (52). Another study showed that education and using ergonomic instruments singly were not effective in prevention of LBP in nurses (29). Hartvigsen showed that although self-satisfaction of nurses about the educational programs was more than 90%, it had a little influence on LBP occurrence (53). A combination of ergonomic education and exercise programs could be a more effective approach (52). Certainly, the results of these interventions are dependent on their quality and the way of follow up (54). The characteristics of the studied population could be a factor of gaining different results in our study compared with other studies. Since this population had a lower mean age with higher capacity of learning and were in better postural condition than older participants of other studies, in addition to very serious and precise follow up for applying and paying attention to the educated contents, they showed more improvement after the intervention. This study showed the prevalence of LBP and NP in hospital personnel, which was related to repetitive tasks, heavy lifting and having wrong posture during job activities. Ergonomic education and precise follow up reduced the risk of MSD, pain intensity and sick leaves and improved their function; thus, since this approach is more cost-effective than ergonomic change in work sites, it could be applicable beside other ways in controlling MSD in hospital personnel.

5.1. Limitations

1-According to free diagnostic and treatment procedure in this hospital, the costs paid by the hospital were not taken into account, except for indirect costs such as work absence and employing alternative personnel.

2- Small sample size of this study was another weak point.

3- Lack of data on other factors influencing MSD such as life style and psychological factors was the last limitation.

5.2. Suggestions

We recommend studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow ups in addition to considering psychological aspects and life styles in different populations with regards to age and sex; also, we suggest performing studies in hospitals with premium diagnostic and treatment procedures.