1. Background

Given the developments in technology nowadays, each year hundreds of new chemicals are produced and utilized in various industries. Several of these chemicals are released in different ways into the atmosphere, water, and soil, which leads to environmental pollution (1). These pollutants can enter the human body in a variety of ways, resulting in adverse effects on human bodies. Damage to reproductive organs and infertility are among the harmful effects of air and water pollution (2-7). Furthermore, many other infertility risk factors, such as cell phone radiation (8, 9), strenuous exercise (10, 11), and stress (12) have been identified and evaluated by researchers. All of the above-mentioned factors result in increased fertility problems.

Other factors such as excessive use of saunas and Jacuzzis (13, 14), increasing body temperature due to fever (15), putting a laptop on the lap, and wearing tight clothing, by increasing scrotum temperature and reducing sperm production, can result in infertility (16, 17). Moreover, inactivity and excessive fast food consumption (18, 19) leading to obesity can create infertility problems, such as testicular dysfunction and reduced sperm count in males (20-23), and polycystic ovarian syndrome, one of the main causes of infertility in females (24) , which most of the time can be treated through lifestyle changes (25, 26). Stress, drinking alcoholic beverages, and smoking can each reduce reproductive potential through various mechanisms (13, 14, 27-33).

Doping, or using anabolic steroids, has the same effect as using androgens or testosterone. These steroids inhibit reproductive hormones, reducing testis size and sperm production, ending in infertility problems (34-36). In females, anabolic hormone use can cause dysmenorrhea, anovulation, and infertility via inhibition of pituitary hormone secretion (37-39).

Findings show that using a cell phone for long periods of time leads to reduction of sperm count and increase of abnormal sperm, resulting in infertility (40, 41). Other factors leading to adverse effects on both male and female fertility are exposure to intense light (42), microwave oven use (43), working in petrochemical industries (44, 45), drinking chlorinated water or swimming in chlorinated swimming pools (6, 46), using certain cosmetic products (47), consuming certain medical drugs (48), pesticide exposure (49), food preservatives (50), and prolonged standing (51).

Unawareness of infertility risk factors has a negative effect on fertility and may result in delayed childbearing. Therefore, evaluating people’s awareness about these factors is essential for preventing the development of infertility worldwide. Many studies in different countries have been carried out about students’ awareness of certain IRFs and have demonstrated that students’ knowledge of IRFs is limited (52-58).

Although several studies in Iran have examined infertility, most of them have focused on infertile patients regarding their knowledge about and attitude toward infertility and infertility treatment techniques, while students’ awareness about infertility risk factors has not been fully studied.

Since college students in each society are considered to be influential, their awareness about infertility risk factors is a key step in preventing infertility and involuntary childlessness.

2. Objectives

In the current study we have evaluated the awareness of college students at Jami institute of technology about different IRFs. Also, since other studies have shown that there may be significant differences between males and females with regard to their knowledge about the causes of infertility (54, 55), we also compared the effects of students’ gender on their awareness.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

Initially, infertility risk factors in males and females were identified by an extensive literature review, and a self-administered questionnaire was designed. The questionnaire was divided into two main sections: 1, demographic information, including age, gender, marital status, and level of education; and 2, a list of infertility risk factors that included 24 questions, each with three answer choices, Yes, No, and I don’t know. In Box 1, a complete list of infertility risk factors for males and females as used in our questionnaire is presented. It should also be mentioned that the reliability and validity of the questionnaire was checked by use of a pre-sampling of size 15.

3.2. Participants

Students of Jami institute of technology, single and married men and women, each with a different level of education, and without considering any other special criteria, were selected as study participants. The participants were selected based on a simple random sampling process. The questionnaires were distributed among the students and filled out by them in May 2015. Participants were assured that their identifying information and responses would be completely confidential. The completed questionnaires were statistically analyzed according to gender.

3.3. Data Analyses

The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 16 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare the means between males and females. Each test with a P less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (Box 1).

| No. | Infertility Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| 1 | Temperature |

| 2 | Cell phone radiation |

| 3 | Light intensity |

| 4 | Air pollution |

| 5 | Low-quality drinking water |

| 6 | Fast food |

| 7 | Stress |

| 8 | Strenuous exercise |

| 9 | Microwave oven use |

| 10 | Doping or using anabolic steroids |

| 11 | Working in petrochemical industries |

| 12 | Prolonged standing |

| 13 | Contact with chlorine in swimming pools |

| 14 | Smoking |

| 15 | Drinking alcoholic beverages |

| 16 | Strenuous activities |

| 17 | Cosmetic products |

| 18 | Wearing tight clothes |

| 19 | Excess chlorine in drinking water |

| 20 | Telecommunication towers |

| 21 | Excessive use of laptops |

| 22 | Pesticides |

| 23 | Food preservatives |

| 24 | Some medical drugs |

List of Infertility Risk Factors Mentioned in the Questionnaire

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ Demographics

123 questionnaires were completed during the study by a total of 123 participants. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

4.2. Male and Female Knowledge of Infertility Risk Factors

Table 2 displays the results of testing the awareness of males and females about infertility risk factors. The results showed that the awareness of females about cell phone radiation, fast food, and stress was significantly higher than that of males. On the other hand, the awareness of males about smoking was significantly higher than of females. There were no significant differences in the awareness of males and females about other infertility risk factors.

| Infertility Risk Factor | Mean Rank of Females | Mean Rank of Males | Mann-Whitney U-test | P < |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 75.41 | 60.79 | 1600.5 | 0.561 |

| Cell phone radiation | 67.77a | 57.23 | 1595 | 0.019 |

| Light intensity | 63.35 | 62.66 | 1931.5 | 0.809 |

| Air pollution | 62.81 | 62.19 | 1902.5 | 0.892 |

| Low quality of drinking water | 61.26 | 63.74 | 1845 | 0.667 |

| Fast food | 69.65a | 55.35 | 1479 | 0.007 |

| Stress | 69.92a | 55.08 | 1462 | 0.004 |

| Strenuous exercise | 64.78 | 61.19 | 1841 | 0.536 |

| Microwaves | 66.93 | 58.07 | 1647.5 | 0.076 |

| Doping | 58.83 | 66.17 | 1694.5 | 0.103 |

| Working in petrochemical industries | 60.70 | 64.30 | 1810.5 | 0.526 |

| Prolonged standing | 62.81 | 62.19 | 1920.5 | 0.916 |

| Contact with chlorine in swimming pools | 66.35 | 58.65 | 1683 | 0.167 |

| Smoking | 67.66a | 75.34 | 1602 | 0.033 |

| Alcohol drinking | 62.53 | 62.47 | 1920 | 0.991 |

| Heavy activities | 58.04 | 66,96 | 1645.5 | 0.133 |

| Cosmetic products | 58.52 | 66.48 | 1675 | 0.186 |

| Wearing tight clothes | 60.44 | 64.56 | 1794.5 | 0.494 |

| Excess chlorine in drinking water | 59.12 | 65.88 | 1712.5 | 0.245 |

| Telecommunication towers | 66.58 | 58.42 | 1669 | 0.083 |

| Excessive use of laptops | 67.81 | 57.19 | 1593 | 0.077 |

| Pesticides | 64.20 | 59.89 | 1757 | 0.445 |

| Preservatives | 66.5 | 58.5 | 1674 | 0.105 |

| Medical drugs | 64.38 | 60.66 | 1808 | 0.229 |

Comparison of Male and Female College Students' Awareness About Infertility Risk Factors by Using Mann-Whitney U test

4.3. General Comparison of Students' Awareness About IRFs at Different Levels of Education

Results showed that the average level of males’ awareness of infertility risk factors at Jami institute of technology was generally lower than that of females (52.27% vs 59.46%) (Table 3).

The female participants studying at the graduate level (MS and PhD) correctly answered the questions slightly more often than the undergraduates among them (associate degree and bachelor of science) (62.42% vs. 56.42%) (Table 3). But in males the awareness of undergraduate students was more than that of graduate students (55.14% vs. 49.40%). But the overall awareness of male and female+ undergraduate and graduate students was similar (55.78% vs. 55.95%).

4.4. General Comparison of Students’ Awareness About Infertility Risk Factors

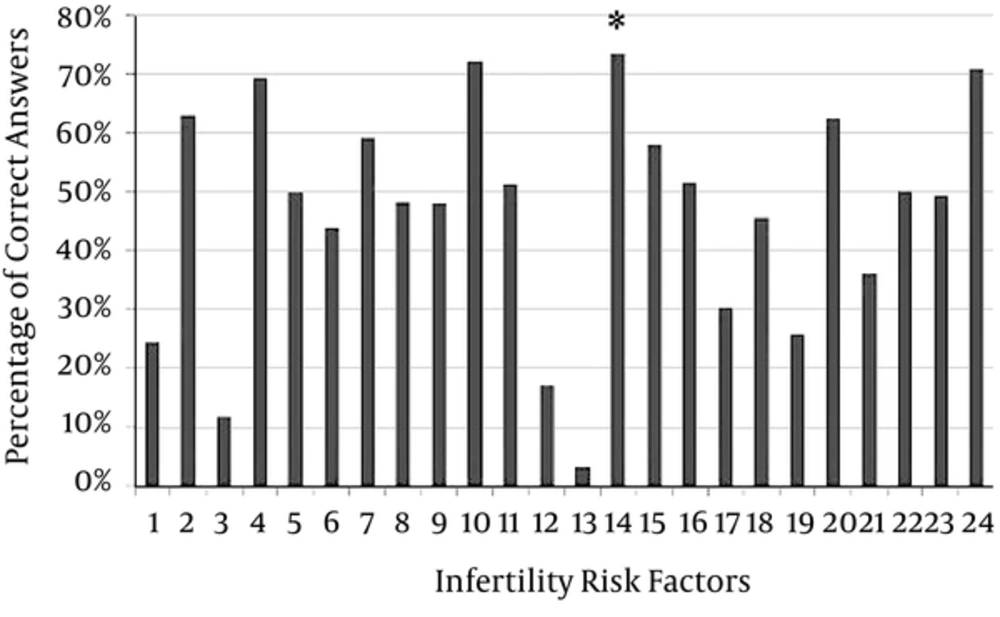

According to Table 3, the general awareness of college students was 55.86%. As shown in Figure 1, the most recognized infertility risk factor among these students was smoking.

| Parameter | Males | Females | Average Awareness of Males and Females |

|---|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate | 55.14 | 56.42 | 55.78 |

| Graduate | 49.40 | 62.5 | 55.95 |

| Average awareness | 52.27 | 59.46 | 55.86 |

Percentage of Infertility Risk Factors Known by Undergraduate and Graduate Males and Femalesa

5. Discussion

Today, infertility is an increasingly significant issue worldwide. Despite the importance of youth knowledge about prevention of infertility and infertility risk factors, these issues are often neglected.

According to our results, male awareness about the adverse effects of smoking on fertility was significantly greater than female, which may be related to the fact that in Iran males are more closely associated with smoking. In contrast to our study, Rouchou et al. illustrated that the awareness of males and females about the effects of smoking on human fertility is almost equal (56). Moreover, in our study smoking was the most recognized infertility risk factor among these students, which could be the consequence of more information in the media about the deleterious effects of smoking.

The significantly greater awareness of female students about cell phone radiation, fast food, and stress than of males which was observed in our study can be related to females’ sensitivity to their fertility, childbearing, and motherhood, and their greater uptake of information from the media. In contrast to our results, in one study it was shown that the awareness of males and females about the effects of radiation on human fertility is equal, also similar proportions of male and female students knew about adverse environmental factors, which is inconsistent with our results (56). Other studies have shown a lack of adequate knowledge about infertility risk factors among college students (52-54) and also significantly higher awareness in females than in males (57). Moreover, Sumera et al. (57) observed that less than half of students are aware of the negative effects of alcohol consumption on fertility, while in our study this was higher (around 60%). This result could be due to the fact that the majority of people in Iran are Muslim and alcohol consumption is prohibited in Islam.

The low levels of awareness about the other mentioned IRFs may be related to lack of sufficient information given about them in the media, schools, and universities.

Our results also demonstrated that higher educational attainment can slightly increase female awareness of infertility risk factors. Since these students’ fields of study are engineering-related, such as chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, and civil engineering, there is no course in the curriculum related to reproduction and fertility; therefore, higher female knowledge about IRFs may be obtained by extra-university study and may be related to their concerns about fertility.

As shown in Table 3, the overall awareness of undergraduate and graduate students is similar, but Sumera et al. showed that people with higher education have better knowledge in comparison to those with less education (57). Consequently, higher education does not increase student awareness about infertility risk factors in Iran, and this is related to the lack of campus teaching about this important subject.

Therefore, our study demonstrates that college students have a moderate level of knowledge about IRFs, that there is a gap relating to these factors, and that unfortunately education cannot be expected to increase their awareness. Therefore, a broad-based approach is needed to improve college students’ knowledge in this area. The results also show that it is beneficial to have a teaching module curriculum that specifically focuses on the topic of infertility risk factors and infertility prevention. However, in order to provide this proposed education, more quantitative statistical studies should be undertaken to determine the content of such a module. In addition to observations from campuses, the media can provide accessible information with the aim of promoting awareness in society about factors that influence fertility, so as to promote reproductive health and prevent infertility in our society.

Our study demonstrates that college students have a considerable knowledge gap relating to risk factors that affect fertility and that the awareness of females is more than that of males. Unfortunately, education cannot be expected to increase their awareness, but more accurate and detailed studies should be conducted in the future.

One of the limitations of the study is the generalizability of the results of this study. Our participants were from one university whose courses are all related to engineering, so our results cannot be representative of the views of other students from other universities and also the general population of Iran. Therefore, it would also be very beneficial to conduct a similar study in other universities and also perform comparisons among them to exactly determine college students’ knowledge about IFRs.

Also, it is possible that, due to the nature of the questions being asked in the questionnaire, some students who were unsure of the answers were persuaded to choose the right answer rather than their actual choice, which is another limitation of this study.