1. Context

As group B Streptococcus is a pathogen commonly found in rectovaginal mucosa of pregnant women, it appears reasonable to label this bacterium as a cause of neonatal diseases at birth (1). Several investigations have revealed that about 10 - 40% of healthy women carry group B Streptococcus in their vagina and/or rectum. Much as the bacterium threatens the fetus in pregnant women, it can also induce infection of the endometrium or amniotic membrane, bacteremia, as well as sepsis and meningitis in susceptible women (2, 3). Since 1970, the etiological role of group B Streptococcus in diseases was highlighted, especially with regard to its ability to cause newborn infections. Recently, two kinds of infantile diseases have been attributed to group B Streptococcus; early-onset diseases and late-onset diseases. The early-onset diseases are usually manifested during the first week after birth, while late-onset diseases may appear 2 - 3 months after birth. Pneumonia and sepsis are both attributed to early-onset diseases; however, late-onset diseases likely engender meningitis in newborn infants.

Albeit different structures have been identified as group B Streptococcus virulence factors, a polysaccharide capsule is known to carry the most important role in this regard (4). It has antiphagocytic function. Other virulence factors include secreted hemolysin, superoxide dismutase, D-alanylated lipoteichoic acid, and some of the surface proteins such as the surface-localized protease CspA. Although surface proteins of Streptococcus agalactiae may have considerable roles during various stages of infection, they attract more and more importance regarding the development of a vaccine. Adhesion to epithelial cells, interactions with human extracellular matrix or plasma proteins, and escape from host immunity are other possible roles of surface proteins of group B Streptococcus (5).

Based on the proportion of cps, group B Streptococcus has been classified into 10 serotypes; Ia, Ib, and II-IX (1, 6). The prevalence rate of group B Streptococcus infections in both pregnant and non-pregnant women varies widely depending on the population studied; however, group B Streptococcus is usually isolated from 10% - 30% of women. In Iran, an estimated average of 9.8% of women is rectovaginally infected; however, the colonization rate of their neonates at birth is not clearly known (7). Some authors believe that about 50 - 75% of infants are exposed to the organism during the birth process (8-10). The major infant’s diseases are attributed to meningitis and septicemia (11, 12). Furthermore, transmission of group B Streptococcus infection to infants at the time of birth, other group B Streptococcus-related infection complications, including premature rupture of membrane, low birth weight, and preterm labor may develop during pregnancy (13).

2. Evidence Acquisition

In the present study, almost all of the literature published from 1992 to July 2019 were reviewed to determine the prevalence of group B Streptococcus carrier state in different regions of Iran. In addition, this study shows the relative frequency of group B Streptococcus positivity with respect to geographical area, date of sampling, and type of the swab specimen.

2.1. Search Strategy

The strategy employed for identifying group B Streptococcus prevalence was searching in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science (ISI), ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and domestic databases for papers published in English or Persian. Terms such as S. agalactiae, group B Streptococcus, S. agalactiae, Streptococcus group B, and Iran were used as keywords to find the relevant published works. In order to find the maximum number of related papers and also gray literature, three local search engines, including the Iranian Scientific Information Database (www.sid.ir), Medlib (www.medlib.ir), and Magiran (www.magiran.com) were used. No limitations were applied when searching the mentioned databases. Extracted references were all reviewed, and the irrelevant titles/abstracts were excluded from the collection. The study selection process was handled by three researchers (MS, AS, NA). To reach a consensus on the selection of the relevant articles, any disagreement was discussed by the team members.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The following publications were identified as eligible to be included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis:

A) Investigations assessing the prevalence of S. agalactiae in the Iranian women,

B) Group B Streptococcus sampling from the vaginal, rectovaginal, endocervical, and rectal regions as well as the urine, and

C) Using culturing and/or PCR method as techniques applied for the detection of group B Streptococcus.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if:

A) They had failed to use a standard method for group B Streptococcus isolation,

B) They had an irrelevant source of sampling (from men, animal, etc.),

C) They were review, meta-analysis or systematic review, or a duplicate publication of the same study.

2.4. Data Collection

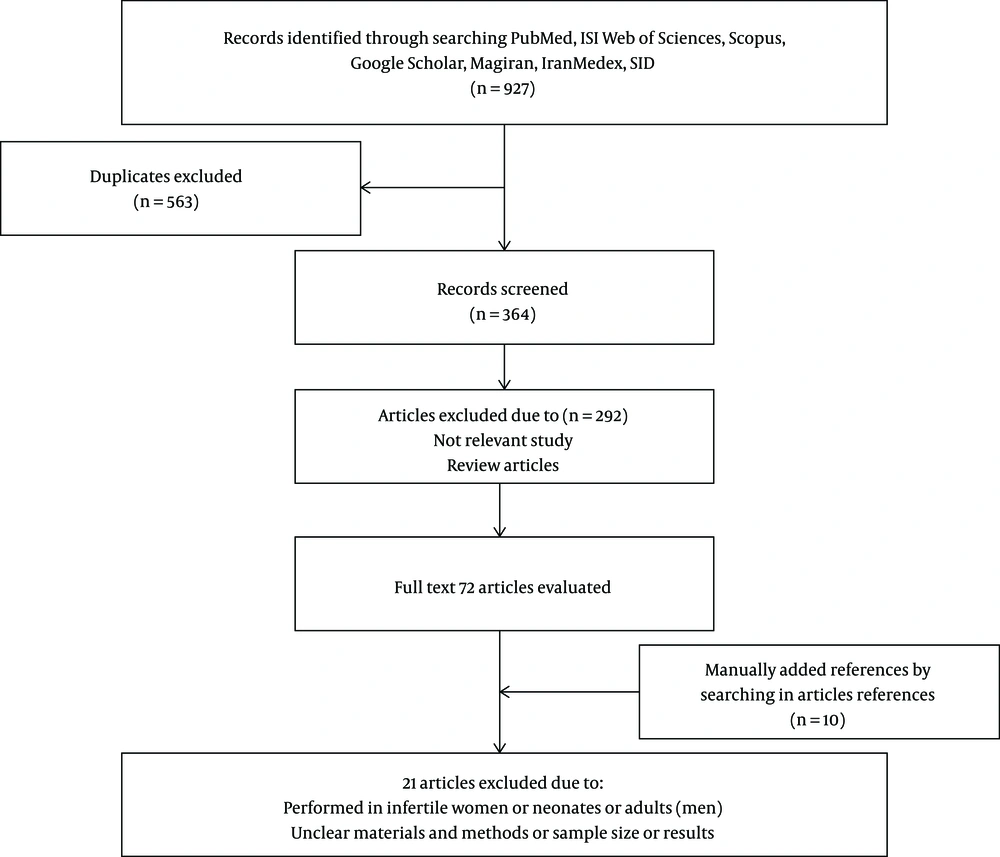

Two authors conducted the data extraction, and the following information was collected: The first author’s name and the date of publication, the participants’ status, including the pregnancy period, geographic location, group B Streptococcus isolation, and finally, the number of group B Streptococcus carriers were all noted for further investigation. Any disagreement as for data collection was discussed by the colleagues to reach the final decision (Figure 1).

2.5. Quality Assessment

In this study, a checklist recommended by Hoy et al. (14) was used for the evaluation of the methodological quality. The checklist consisted of nine questions, representing the sampling-related information, technique of sampling, the response rate, the technique applied for data collection, tools for measurement, definition of cases, and the statistical method. Each question was scored 1 or 0, defined as low- or high-risk bias, respectively. Scores 0 to 9 were selected and defined as follows: 0 to 3 as “high-risk”, 4 to 6 “moderate-risk”, and 7 to 9 as “low-risk” bias.

2.6. Limitations

The overall prevalence of group B Streptococcus carriers in our query could not be determined comprehensively. Different factors such as geographical region, collection of samples, site of sampling, socioeconomic status, and microbiological methods all contributed to the results obtained. Also, due to lack of group B Streptococcus prevalence works in some provinces such as Golestan, Semnan, Mazandaran, Zanjan, Qom, South Khorasan, North Khorasan, Sistan and Baluchestan, Hormozgan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Alborz, Qazvin, and West Azarbaijan, this review paper failed to present a full account of group B Streptococcus prevalence in Iran (Figure 2).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The total number of the participants and the number of samples with S. agalactiae were used to calculate the event rate and confidence interval. The summary estimates were derived using the DerSimonial and Laird random effects model by taking inter-study heterogeneity into account. The I-squared and Cochran’s Q tests were used to assess heterogeneity between the studies. Subgroup analysis was used to explore the prevalence rates according to the sampling year, the province in which the study was conducted, and the quality of studies. Sensitivity analysis was carried out to explore the extent to which the overall calculations might depend on a specific study. All analyses were performed using the STATA software version 11.2 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

According to Databases, 927 articles were selected, among which 563 duplicated articles were excluded. Following reviewing all abstracts of the published works, 292 articles were deleted because of being irrelevant. Full texts of 82 articles were carefully considered, and again, 21 articles that were directly related to infertile women, neonates, adults, and those with ambiguous methods were all excluded from the study. Overall, the remaining 61 articles were approved for further investigation (Figure 1).

3.1. Prevalence of Group B Streptococcus in Iranian Women

Extraction of the information of these articles revealed 36,807 pregnant and non-pregnant women had been examined for group B Streptococcus detection during 1992 - 2018, out of which 2,930 cases (9.7%) were found positive for group B Streptococcus (Table 1). Observed data demonstrated the prevalence of group B Streptococcus among pregnant women to be 11.9% (95% CI: 0.103 - 0.135). Based on swab sampling technique, positive cases were found as the following: (1) vaginal samples with 34 studies (12.9%) (95% CI: 0.103 - 0.155), (2) recto-vaginal samples with 25 studies (9.7%) (95% CI: 0.075 - 0.120), rectum samples with 10 studies (18.5%) (95% CI: 0.096 - 0.275), endocervical samples with one study (3.7%) (95% CI: -0.003 - 0.077), vaginal and urine with one study (6.1%) (95% CI: 0.030 - 0.092), and urine with three studies (2.3%) (95% CI: 0.001 - 0.044). When the recorded data regarding distribution of group B Streptococcus among non-pregnant women were extracted, 5.3% (95% CI: 0.034 - 0.072) of the cases were identified as group B Streptococcus colonized.

| First Author (Ref. No.) | Place (City) | Year (yr) | Age | Pregnancy | Pregnancy Age (wk) | Swab Samples | Identification Method | Sample Size | No. Positive GBS | Carriers (%) | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aali (15) | Kerman | 2005 | 25.6 | Preg | 38-40 | Vag | Cult | 105 | 7 | 6.7 | Low-risk |

| Absalan (16) | Yazd | 2002 | 15-40 | Preg | Recto-Vag | Cult. PCR | 250 | 49 | 19.6 | Low-risk | |

| Ahmadi (17) | Sanandaj | 2017 | 19-43 | Preg | 35-37 | Endocervical | PCR | 109 | 4 | 3.7 | Moderate-risk |

| Akhlaghi (18) | Mashhad | 2007 | NA | Preg | 33-37 | Vag | Cult | 43 | 3 | 7 | Moderate-risk |

| Arzanlou (2) | Ardabil | 2008 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 420 | 56 | 13.3 | Low-risk |

| Bakhtiari (19) | Tehran | 2011 | NA | Preg | 28-38 | Recto- Vag | Cult. PCR | 375 | 35 | 9.3 | Moderate-risk |

| Bidgani (20) | Ahvaz | 2013-2014 | 16-45 | Preg | 28-38 | Vag | Cult. PCR | 137 | 38 | 27.7 | Moderate-risk |

| Preg | Rect | Cult. PCR | 137 | 42 | 30.7 | Moderate-risk | |||||

| Bornasi (21) | Arak | 2012 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult. PCR | 500 | 60 | 12 | Moderate-risk |

| Soltan Dalal (22) | Tehran | 2008 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult. PCR | 125 | 10 | 8 | Low-Risk |

| Darabi (23) | Tehran | 2014-2015 | 18-35 | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 186 | 22 | 11.8 | Moderate-risk |

| Daramroodi (24) | Kermanshah | 2017 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult. PCR | 100 | 5 | 5 | Moderate-risk |

| Fatemi (25) | Tehran | 2008 | 16-40 | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult, PCR | 330 | 68 | 20.6 | Moderate-risk |

| Fazeli (26) | Amol | 2013 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult, PCR | 100 | 4 | 4 | Moderate-risk |

| Rect | Cult, PCR | 100 | 3 | 3 | Moderate-risk | ||||||

| Recto- Vag | Cult, PCR | 100 | 3 | 3 | Moderate-risk | ||||||

| Frouhesh (27) | Tehran | 2011-2012 | NA | Non-preg | - | Urine | Cult | 5000 | 104 | 2.1 | High-risk |

| Ghanbarzadeh (28) | Birjand | 2013-2014 | 16-37 | Preg | 30 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 500 | 26 | 5.2 | Moderate-risk |

| Goudarzi (29) | Khorramabad | 2012 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult, Real-time PCR | 100 | 17 | 17 | Moderate-risk |

| Habibzadeh (30) | Ardabil | 2010 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 420 | 19 | 4.5 | Moderate-risk |

| Rect | Cult | 420 | 19 | 4.5 | Moderate-risk | ||||||

| Recto- Vag | Cult | 420 | 24 | 5.7 | Moderate-risk | ||||||

| Hadavand (31) | Tehran | 2010-11 | 15-44 | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 210 | 7 | 3.3 | Moderate-risk |

| Hamedi (32) | Mashhad | 2008-2009 | 15-39 | Preg | 34-40 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 200 | 12 | 6 | Moderate-risk |

| Hassanzadeh (33) | Shiraz | 2006-2007 | 19-35 | Preg | < 20 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 310 | 43 | 13.9 | Low-risk |

| Jannati (2) | Ardabil | 2012 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 420 | 56 | 13.3 | Moderate-risk |

| Javadi (34) | Isfahan | 2004 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 170 | 31 | 18.2 | |

| Javanmanesh (35) | Tehran | 2012 | 16-42 | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 1028 | 234 | 22.8 | Low-risk |

| Kabiri (36) | Jahrom | 2014 | 16-40 | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 403 | 66 | 16.4 | Low-risk |

| Rect | 21 | 5.2 | Low-risk | ||||||||

| Recto- Vag | 7 | 1.7 | Low-risk | ||||||||

| Kalantar (37) | Sanandaj | 2011-2012 | 18-37 | Preg | 28-38 | Vag | PCR | 200 | 123 | 61.5 | Moderate-risk |

| Rect | PCR | 200 | 160 | 80 | Moderate-risk | ||||||

| Kasraeian (38) | Shiraz | 2007 | 18-36 | Preg | 18 | Urine | Cult | 389 | 1 | 0.3 | Low-risk |

| Khoshkhoutabar (39) | Arak | 2013 | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 268 | 14 | 5.2 | Moderate-risk | |

| Malek-Jafarian (40) | Mashhad | 2015 | 15-40 | Non-preg | Urine Vag | Cult | 1200 | 46 | 3.8 | Moderate-risk | |

| Mansouri (41) | Kerman | 2006-2007 | 20-35 | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 602 | 55 | 9.1 | Moderate-risk |

| Mashouf (42) | Hamadan | 2013-2014 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult. PCR | 203 | 15 | 7.4 | Moderate-risk |

| Mobasheri (43) | Ardal | 2010 | 17-38 | Preg | 0-40 | Vag | Cult | 85 | 2 | 2.3 | Moderate-risk |

| Nakhaei Moghaddam (44) | Mashhad | 2005-2007 | 16-40 | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 201 | 22 | 10.9 | Moderate-risk |

| Rect | Cult | 201 | 24 | 11.9 | Moderate-risk | ||||||

| Mohamadi (45) | Ilam, | 2014-2015 | 16-42 | Preg | < 35 | Vag | Cult | 90 | 4 | 4.4 | Moderate-risk |

| Mousavi (46) | Hamadan | 2013-2014 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult. PCR | 203 | 15 | 7.4 | Moderate-risk |

| Saghafi (47) | Mashhad | 2015-2016 | 15-42 | Preg | 27-37 | Vag | Cult | 200 | 3 | 2 | Moderate-risk |

| Nahaei (13) | Tabriz | 2001-2002 | NA | Preg | NA* | Vag | Cult | 965 | 17 | 1.8 | Moderate-risk |

| Namavar Jahromi (48) | Shiraz | 2003 | 14-45 | Preg | > 24 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 1197 | 110 | 9.2 | Moderate-risk |

| Nasri (49) | Arak | 2010 | 16-39 | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 186 | 30 | 16.1 | Moderate-risk |

| Nazari (50) | Yazd | 2015-2016 | 15-40 | Preg | NA | Vag | Cult | 346 | 57 | 16.5 | Moderate-risk |

| Urine | Cult | 346 | 33 | 9.5 | Moderate-risk | ||||||

| Nazer (51) | Khorram Abad | 2009 | 18-39 | Preg | 28-37 | Vag | Cult | 100 | 14 | 14 | Low-risk |

| Pirouz (52) | Tehran | 1992 | 15-43 | Preg | > 37 | Vag | Cult | 200 | 34 | 17 | Moderate-risk |

| Rabiee (53) | Hamadan | 2006 | 18-35 | Preg | > 20 | Vag | Cult | 544 | 145 | 26.7 | Moderate-risk |

| Rahbar (54) | Tehran | 2010 | 26.6 ± 19.37 (mean) | Preg | NA | Urine | Cult | 11800 | 19 | 0.2 | Moderate-risk |

| Non-Preg | - | Urine | Cult | 11800 | 479 | 4.1 | Moderate-risk | ||||

| Sadeh (9) | Yazd | 2013-2014 | 15-40 | Preg | NA | Recto- Vag | Cult. PCR | 237 | 30 | 12.7 | Moderate-risk |

| Non-Preg | - | Recto- Vag | Cult. PCR | 413 | 70 | 16.9 | Moderate-risk | ||||

| Zarean Seyyed (55) | Isfahan | 2010-2011 | 17-42 | Preg | 37 | Rect | Cult | 178 | 30 | 16.9 | Low-risk |

| 17-36 | 20-37 (Preterm labor) | Rect | Cult | 151 | 55 | 36.4 | Low-risk | ||||

| 17-42 | 37 | Vag | Cult | 178 | 36 | 20.2 | Low-risk | ||||

| 17-36 | 20-37 (Preterm labor) | Vag | Cult | 151 | 59 | 39.1 | Low-risk | ||||

| Sharifi (56) | Tehran | 2011 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 250 | 21 | 8.4 | Moderate-risk |

| Shirazi (57) | Tehran | 2009-2011 | 19-50 | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 980 | 48 | 4.9 | Low-risk |

| Tajbakhsh (58) | Bushehr | 2010-2011 | 26.39 ± 5.33 mean | Preg | 35-42 | Vag | Cult | 285 | 27 | 9.5 | Low-risk |

| Yasini (59) | Kashan | 2011-2012 | 16-45 | Preg | 28-37 | Vag | Cult | 382 | 36 | 9.4 | Moderate-risk |

| Zamanzad (60) (unpublished Persian article) | Shahrekord | 2000 | NA | Preg | Vag | Cult | 624 | 110 | 17.6 | Moderate-risk | |

| Amirmozafari (61) | Rasht | 2005 | Preg | 28-37 | Vag | Cult | 100 | 15 | 15 | High-risk | |

| Haghshenas Mojaveri (62) | Babol | 2014 | 25.9 ± 4.2 (mean) | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 400 | 31 | 7.8 | Low-risk |

| Rect | Cult | 400 | 20 | 5 | Low-risk | ||||||

| Recto- Vag | Cult | 400 | 10 | 2.5 | Low-risk | ||||||

| Jahed (63) | Tehran | 2008 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Recto- Vag | Cult | 246 | 13 | 5.3 | Moderate-risk |

| Khataie (64) | Tehran | 1998 | NA | Preg | 37 | Vag | Cult | 191 | 28 | 14.7 | Moderate-risk |

| Nasrollahi1 (65) | Sari | 2018 | < 25-30 > | Preg | 35-37 | Vag, Urine | Cult, PCR | 246 | 15 | 6.1 | Moderate-risk |

| Rostami (66) | Isfahan | 2015 | 29.35 ± 5.509 (mean) | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult, PCR | 200 | 22 | 11 | Low-risk |

| Rect | Cult, PCR | 200 | 7 | 3.5 | Low-risk | ||||||

| Sahraee (67) | Rasht | 2017-2018 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult, PCR | 245 | 19 | 7.8 | Moderate-risk |

| Rect | 245 | 24 | 9.8 | Moderate-risk | |||||||

| Abdollahi Fard (68) | Tabriz | 2006 | 22.96 ± 3.89 (mean) | Preg | 35-37 | Vag, Rect | Cult | 250 | 24 | 9.6 | Moderate-risk |

| Akbarian Rad (69) | Babol | 2012-2014 | 25.7 ± 5.55 (mean) | Preg | > 26 | Vag, Rect | Cult | 410 | 46 | 11.2 | Moderate-risk |

| Shahbazian (70) | Ahvaz | 2007 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag, Rect | Cult | 250 | 33 | 13.2 | High-risk |

| Sarafrazi (71) | Kashan | 2000 | NA | Preg | 35-37 | Vag | Cult | 400 | 32 | 5.8 | High-risk |

Abbreviations: Cult, culture; GBS, Group B Streptococcus; NA, not available; Preg, pregnant; Rect, rectal; Rect-Vag, rectovaginal; Vag, vaginal.

3.2. Prevalence of Group B Streptococcus in Vaginal and Rectovaginal Swabs of Pregnant Women

The majority of group B Streptococcus research works were based on vaginal or rectovaginal samples. Therefore, an effort was made to analyze and record the data in terms of city, quality assessment index, and year of publication (Tables 1 and 2). The papers were then classified into high-, moderate-, and low-quality index, and consequently, we found vaginal swab samples were in the low-risk (13.7%) group, while rectovaginal cases were in the high-risk (13%) group. Further observation indicated the prevalence of group B Streptococcus from vaginal samples was 15.8% before the year 2000; the city of Sanandaj carried the highest rate with 61.5%, and Tabriz recorded the lowest incidence with 1.8% (Table 2). Data observed from rectovaginal samples (Table 3) revealed that the highest incidence of group B Streptococcus had been observed in 2000 - 2009, during which Isfahan had suffered from the highest rate (18.2%), but Jahrom had the lowest rate (1.7%).

| Sample | Number of Studies | Prevalence | 95% CI | Heterogeneity | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q- Statistic | I-Squared (%) | P Value | |||||

| Experiment date | |||||||

| < 2000 | 2 | 15.8 | 0.122-0.194 | 0.40 | 0.0 | 0.528 | < 0.001 |

| 2000 - 2009 | 12 | 11.8 | 0.076-0.160 | 339.12 | 96.8 | 0.000 | |

| ≥ 2010 | 20 | 13.4 | 0.096-0.172 | 454.24 | 95.6 | 0.000 | |

| City | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Kerman | 2 | 8.7 | 0.066-0.108 | 0.76 | 0.0 | 0.384 | |

| Yazd | 1 | 16.5 | 0.126-0.204 | 0.00 | |||

| Sanandaj | 1 | 61.5 | 0.548-0.682 | 0.00 | |||

| Mashhad | 3 | 6.4 | -0.003-0.131 | 13.25 | 84.9 | 0.001 | |

| Ardabil | 2 | 4.1 | 0.023-0.059 | 0.84 | 0.0 | 0.359 | |

| Tehran | 4 | 14.1 | 0.053-0.230 | 68.97 | 95.7 | 0.000 | |

| Ahvaz | 1 | 27.7 | 0.203-0.352 | 0.00 | |||

| Arak | 2 | 13.4 | 0.096-0.173 | 1.80 | 44.4 | 0.180 | |

| Kermanshah | 1 | 5 | 0.003-0.097 | 0.00 | |||

| Amol | 1 | 4 | -0.003-0.083 | 0.00 | |||

| Khorramabad | 1 | 14 | 0.071-0.209 | 0.00 | |||

| Isfahan | 2 | 23.1 | 0.082-0.381 | 38.77 | 94.8 | 0.000 | |

| Jahrom | 1 | 16.4 | 0.128-0.200 | 0.00 | |||

| Hamadan | 3 | 13.8 | 0.012-0.264 | 69.17 | 97.1 | 0.000 | |

| Ilam | 1 | 4.4 | -0.003-0.092 | 0.00 | |||

| Tabriz | 1 | 1.8 | 0.009-0.026 | 0.00 | |||

| Bushehr | 1 | 9.5 | 0.060-0.129 | 0.00 | |||

| Kashan | 2 | 8.6 | 0.067-0.106 | 0.48 | 0.0 | 0.487 | |

| Shahrekord | 1 | 17.6 | 0.146-0.206 | 0.00 | |||

| Rasht | 2 | 10.7 | 0.037-0.177 | 3.26 | 69.3 | 0.071 | |

| Babol | 1 | 7.8 | 0.051-0.104 | 0.00 | |||

| Quality assessment | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Low-risk | 8 | 13.7 | 0.090-0.184 | 124.62 | 93.6 | 0.000 | |

| Moderate-risk | 24 | 12.8 | 0.093-0.163 | 729.01 | 96.8 | 0.000 | |

| High-risk | 2 | 10.7 | 0.040-0.174 | 3.28 | 69.5 | 0.000 | |

| Overall | 34 | 12.9 | 0.103-0.155 | 865.91 | 96.1 | 0.000 | < 0.001 |

| Sample | Number of Studies | Prevalence | 95% CI | Heterogeneity | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q- Statistic | I-Squared (%) | P Value | |||||

| Experiment date | < 0.001 | ||||||

| < 2000 | 0 | - | - | - | |||

| 2000 - 2009 | 10 | 11.3 | 0.087-0.139 | 49.39 | 81.8 | 0.000 | |

| ≥ 2010 | 15 | 8.7 | 0.056-0.117 | 286.00 | 95.1 | 0.000 | |

| City | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Yazd | 2 | 16 | 0.092-0.228 | 4.36 | 77.1 | 0.037 | |

| Mashhad | 1 | 6 | 0.026-0.094 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Ardabil | 3 | 10.7 | 0.052-0.162 | 21.40 | 90.7 | 0.000 | |

| Tehran | 7 | 9.9 | 0.041-0.156 | 132.41 | 95.5 | 0.793 | |

| Ahvaz | 1 | 13.2 | 0.090-0.174 | 0.00 | . | 0.000 | |

| Arak | 1 | 5.2 | 0.025-0.080 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Amol | 1 | 3 | -0.010-0.070 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Birjand | 1 | 5.2 | 0.032-0.072 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Khorramabad | 1 | 17 | 0.096-0.244 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Shiraz | 2 | 11.2 | 0.067-0.157 | 4.77 | 79.0 | 0.029 | |

| Isfahan | 1 | 18.2 | 0.124-0.241 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Jahrom | 1 | 1.7 | 0.004-0.031 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Tabriz | 1 | 9.6 | 0.059-0.133 | 0.00 | . | . | |

| Babol | 2 | 6.8 | -0.018-0.153 | 24.23 | 95.9 | 0.000 | |

| Quality assessment | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Low-risk | 6 | 12.2 | 0.049-0.195 | 281.57 | 98.2 | 0.000 | |

| Moderate-risk | 16 | 8.1 | 0.065-0.097 | 67.98 | 77.9 | 0.000 | |

| High-risk | 3 | 13 | 0.076-0.183 | 7.01 | 71.5 | 0.000 | |

| Overall | 25 | 9.7 | 0.075-0.120 | 373.41 | 93.6 | 0.000 | < 0.001 |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The present systematic review and meta-analysis has summarized 61 published works on group B Streptococcus distribution in Iran. Among 36,807 samples examined, 2,930 samples (9.7%) were reported positive for group B Streptococcus. The prevalence was estimated to be 11.9% in pregnant and 5.3% in non-pregnant women (Table 1). The worldwide investigations show that a total of 11% - 30% of women are carriers of group B Streptococcus in their genital system. The important point is that contaminated women may transfer the bacterium to their fetus or neonates (9, 45, 72).

The knowledge resulting from the present review of group B Streptococcus colonization allows us to conclude that since up to 9.7% of females have been found to be group B Streptococcus-positive, it seems reasonable to suggest a strengthened program for screening the pregnant women to illuminate the more accurate prevalence of group B Streptococcus among the Iranian population. Moreover, a variation was discovered in the reported data, which could be mainly due to different methods for group B Streptococcus detection. Therefore, it is essential to document a more sensitive method for the studies to come. Furthermore, more serious measures are needed to represent an account of group B Streptococcus in infected pregnant women for preventing the transmission of bacterium to their neonates. Additionally, a treatment program must be optimized to eradicate the infection in pregnant women and carriers. Finally, despite controversy in reported data from different populations, group B Streptococcus is surely present in different races around our country. As a result, documenting a legal program is highly recommended for screening pregnant women in rural and low-income populations in this country.