1. Coronavirus Disease

Coronaviruses are major pathogens that mainly target the human respiratory tract. The previous outbreaks of coronaviruses, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), showed to be highly threatening for public health. In late December 2019, several patients were admitted to hospitals whose initial diagnosis was pneumonia of unknown etiology. These patients were linked to a seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, Hubei province, China (1, 2). Coronaviruses include a large family of viruses that are responsible for a subset of diseases varying from the common cold to more severe infections including SARS, MERS, and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). The latest type of them spreading to humans is COVID-19 (3). Initial reports predicted the start of a potential coronavirus epidemic with estimates of the basic reproduction number (R0) for the new (COVID-19, designated by the World Health Organization on 11 February 2020), which was significantly higher than one (ranging from 2.24 to 3.58) (4).

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the cause of COVID-19 (5). Nowadays, COVID-19 is spread worldwide, resulting in the century pandemic (6, 7). The main symptoms of COVID-19 are high temperature (fever), cough, and shortness of breath. The affected patients develop pneumonia and multi-organ failure ending to death. Almost all expired patients had severe comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus (8, 9). Wang et al. showed that the median time from obvious symptoms to death was two weeks, but in some cases, it lasted up to six weeks (10). Many factors can affect the mortality rate. According to the current research and knowledge, accessibility to medical services, and socioeconomic status can play important roles in this regard (11). The sharp trend of this pandemic infection is life-threatening for humans and must ring a bell for everyone, especially at-risk patients.

At present, the novel coronavirus has a mortality rate of about 2% to 3%, but it possibly changes as the virus continues to spread, while SARS virus mortality is about 14% to 15%. Most deaths of COVID-19 occur in elderly people with other health problems such as heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes. According to statistics, this group of people is at greater risk of death than others due to diseases like the flu (8).

2. COVID-19 Infection and Acute Renal Failure

To find the relationship between COVID-19 infection and acute renal failure, in this review, international databases, including the Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Goggle scholar, were searched for articles up to 17 March 2020. Keywords were COVID-19, coronavirus disease, SARS-CoV-2, kidney, renal function, acute kidney injury, and acute renal failure, or a combination of them in title/abstracts. For the sensitivity of the search, after examining the titles, irrelevant studies were removed, and the remaining studies were assessed by relevant specialists. The syntax sample for PubMed was as follows: ((((COVID-19 [Title/Abstract]) OR coronavirus [Title/Abstract]) OR SARS-CoV-2 [Title/Abstract])) AND (((renal function [Title/Abstract]) OR renal [Title/Abstract]) OR acute kidney failure [Title/Abstract]) OR acute renal failure [Title/Abstract])) AND (("2019/01/12"[PDat]: "2020/03/17"[PDat])).

We know that renal and heart failures are life-threatening events. According to the study by Dong et al., on 2,143 pediatric patients with COVID-19 in China, children with COVID-19 can quickly progress to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), resulting in shock, encephalopathy, heart failure, coagulopathy, and acute renal failure injury (12). Given that COVID-19 makes patients susceptible to dysfunction in multiple organs, including the cardiovascular system, digestive tract, nervous system, and kidneys, the question is that what is the treatment method in the affected patients with renal failure (13)? For responding to this question, it is essential to review the treatment of patients in similar conditions, e.g., people developing SARS or MERS. MERS and SARS are similar viral diseases affecting many people, and compared to COVID-19, they have high mortality rates of about 37% and 10%, respectively. However, both of them are less contagious than COVID-19. The COVID-19 disease is very contagious, with a lower mortality rate than MERS and SARS (14, 15).

Another reason facilitating the spread of transmission is the similarity of COVID-19 to influenza. Both diseases have similar symptoms causing respiratory involvement and sometimes death. Additionally, they both are transmitted by contact and T-zone contamination by droplets and fomites. Measures to prevent their development are the same, including keeping hand hygiene and using respiratory masks (16, 17). Transmission is the fundamental issue in epidemics, and the passengers are the main transporters of the virus to other countries. More than 30% of transmission cases happen by the nosocomial route, and it is the main route of transmission for coronavirus infections in adults. The possibility of virus transmission from children to other people has been approved. Since children develop mild symptoms without the need for hospitalization, the rate of contact, and infection transmission from children to health care workers is low (18-22). One-third of COVID-19 cases had exposure to the epidemic area, and about 90% of children had close contact with their family (23).

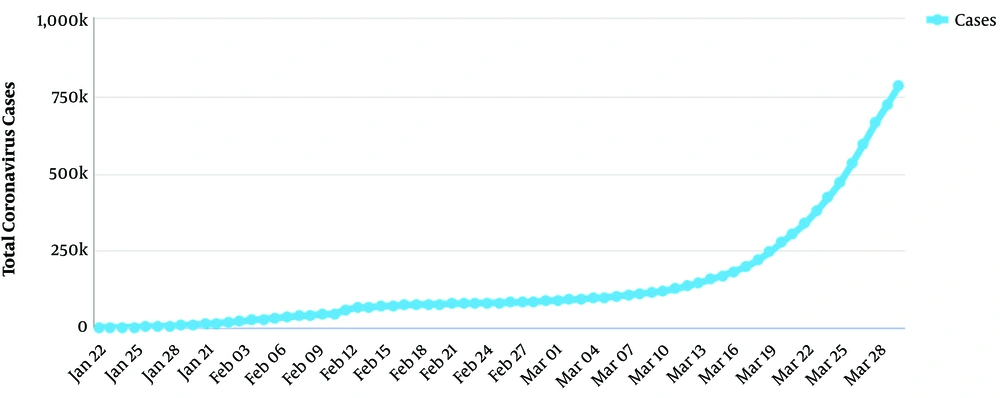

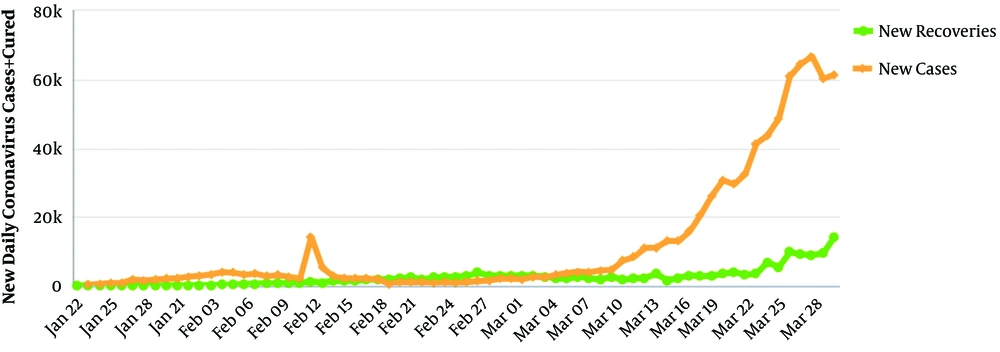

Figures 1 and 2 show the sharp increasing trend of the epidemiologic curve by 1 April 2020. MERS, similar to COVID-19, is often accompanied by Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) and organ dysfunction (24). Regarding kidney injury following coronavirus infections, MERS is responsible for severe renal involvement that drastically affects the kidneys as it is not observed in any other human coronavirus infection. However, the mechanism of renal failure following MERS is not known exactly (25, 26). It is possible that restricting oxygen to vital organs can cause dysfunction in the kidneys and the brain.

Unlike other coronaviruses that mostly affect the human respiratory tract, the virus can affect various organs, including respiratory tissues, liver, kidneys, intestine, and body's immune cells. That is why patients usually have multiple dysfunctions and finally pass away (5). Studies showed acute renal failure during MERS and SARS, but SARS is less likely to affect kidney epithelial cells. In contrast, acute renal failure was observed in many patients with MERS influencing the severity of disease (27, 28).

3. Diagnostic Methods

By the early diagnosis, the sharp trend gets wider in such a way that the isolation of affected people can interrupt the chain of transmission. The standard method of COVID-19 diagnosis is real-time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (rRT-PCR). Another method includes nasopharyngeal swabs and blood sampling, but it takes 14 days, and in this situation cannot be a suitable method (6, 29, 30).

4. Treatment of Acute Renal Failure Following COVID-19 Infection

After diagnosis, the supportive treatment should start as soon as possible. Regarding renal failure, COVID-19 patients whose disease is accompanied by renal failure should receive supportive treatment as it is done for patients with renal failure without COVID-19. Also, kidney replacement therapy is another choice for them. By now, no effective antiviral medication exists to treat these patients. New medicines cannot be prescribed without approved results (31). All routine measures for people affected with COVID-19 can also be done for COVID-19 patients with acute renal failure until the current knowledge is changed because this disease is a new pandemic that will be more clear in the future; the current knowledge may be changed by attaining new information in this regard (32). To the best of our knowledge, COVID-19 tends to involve multiple organs, and the kidney is one of them, as shown in two studies. Acute kidney injury was reported in 5.1% of the patients. Patients with renal failure have a higher risk to be expired (33-36). Various studies report multiple-organ failure. Regarding the lungs, about half of the patients were involved with moderate pneumonia, and 20% have acute upper respiratory symptoms. Chu et al. showed that 6.7% of the patients developed acute renal impairment at a median duration of 20 days after the onset of disease (33, 37). Liver impairment was reported in about 60% of the patients with the elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (38).

5. Common Symptoms in COVID-19 Patients with Renal Failure

Studies revealed the high rate of renal involvement in patients with COVID-19. Two common symptoms in COVID-19 patients with renal failure are hematuria and proteinuria as albumin in the urine. Another major issue is impaired renal function in COVID-19 patients so that two-thirds of expired patients experienced kidney dysfunction, and about one-fourth of discharged COVID-19 patients had impaired renal function. These symptoms are life- threatening, especially in patients with other comorbidities. Only 15% of the kidney function remained in COVID-19 patients. This can be a crucial symptom for the diagnosis of COVID-19 in patients with flu-like symptoms. It means that patients with renal failure should be checked regarding COVID-19 in the present and future. The authors think that a differential diagnosis (DDX) of acute renal failure should be COVID-19.

Understanding the fact that multi-organ dysfunction following COVID-19 is the main cause of death in patients necessitates it for clinicians to be alert because multiple-organ failure such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, heart failure, and renal failure in the present infection is sophisticated to be treated (39). Particularly, infants, people more than 60 years, pregnant women, and in-patients with severe comorbidities are vulnerable to COVID-19 and should stay at the intensive care unit. We know that COVID-19 involves the kidneys and results in acute renal failure, but in patients with chronic kidney disease, the effect of the virus is vague and unknown (40).

6. Do ACE Inhibitors Influence COVID-19 Disease?

On 15 March 2020, the Renal Association of the UK asserted that Angiotensin-converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers could not increase the chance of mortality by COVID-19 disease in such a way that provoking anxiety in patients with kidney disease is threatening. After stopping the ACE inhibitors, heart failure may arise. Breathlessness can be intensified by stopping the drugs of interest so that it makes it hard for clinicians to distinguish whether the symptoms are due to underlying health problems or COVID-19 disease. Stopping the drugs depends on the clinical condition except for having COVID-19 infection. Therefore, taking ACE inhibitors is not precluded (41, 42). The authors think that another differential diagnosis (DDX) of flu-like symptoms should be the use of ACE inhibitors. Now, there are no exact statistics about the number of COVID-19 patients developing acute renal failure; for example, we do not know what percentage of 7,426 COVID-19 patients by March 17 died due to acute renal failure (27). The importance of this event will be clear after new cohort studies and further cross-sectional assessments.

7. Chloroquine for COVID-19 Infection

So far, there is no approved drug for treating COVID-19 patients not only for antiviral effects but also for other symptoms including acute renal failure. Considering that acute renal failure arises after COVID-19 development, it seems that the treatment of COVID-19 disease is useful on the path of renal impairment treatment. Starting antiviral medications is proposed to maintain vital organs function; hence, it can reduce the morbidity and mortality among critical patients (43, 44). Chloroquine is a quinine of amine acidotropic form, first synthesized in Germany in approximately 85 years ago (45). Chloroquine inhibits the completion of the viral cycle with the binding of viral particles to cellular cell receptors (46, 47). Chloroquine phosphate has been widely used as a medication to treat malaria for several years. It has apparent efficacy with enough safety in patients with COVID-19, as multicenter trials approved its effect in China. Also, chloroquine may be included in the next version of guidelines to treat COVID-19 issued by the National Health Commission in China (48).

The benefits of chloroquine can be summarized as follows: "chloroquine prevents SARS Cov-2 replication", "chloroquine slows down the activity of lots of viruses in vitro", "acute viral diseases in humans have been treated using chloroquine for several years", and "big data in China show the effective role of chloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19" (49). Also, chloroquine is used to treat chronic viral diseases such as HIV infection (50). Additionally, hydroxychloroquine is used in systematic immunodeficiency diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (51). Besides the wide use of chloroquine in different viral infections, the treatment of patients with COVID-19 infected by SARS-CoV-2 was observed (49). The multicenter collaboration group of China reported that chloroquine phosphate (chloroquine) had acceptable antiviral effects, including against coronaviruses, increased the chance of treatment, reduced stay at the hospital, and led to discharge with good condition in COVID-19 patients. The group recommended using 500 mg chloroquine phosphate tablets twice per day up to 10 days (52, 53).

8. Positive RT-PCR Test After Recovery From COVID-19 Infection

On 17 February 2020, four discharged patients were reported to be a new challenge in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 infection. Thus, follow-ups should be considered regularly by telephone or email in these patients. Patients' e-mails are intended to reduce both in-person visits and the risk of recurrence because the best way to prevent COVID-19 infection is to keep far from exposure to the virus (30, 54). Although there were only four patients, which are not enough to make a clinical decision, it can make us aware of the importance of following up.

9. Conclusions

It is important to check creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), proteinuria, and hematuria on admission because patients with elevated creatinine are at risk of mortality two times more than patients with normal creatinine. Also, elevated BUN of about four times, proteinuria up to four times, and hematuria up to five times can increase the risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19. Considering that about 5% of patients referring to hospitals develop renal failure, it is important to check creatinine, BUN, proteinuria, and hematuria in the primary assessment. Taking the ACE inhibitors can be useful and its stoppage is not recommended. Chloroquine phosphate may improve the chance of treatment. Due to the probability of COVID-19 recurrence after recovery, the follow-up should be considered regularly by telephone or email in these patients. Generally, all routine measures for people affected by COVID-19 can be done for COVID-19 patients with acute renal failure until the current knowledge is changed. It is proposed to perform longitudinal studies to assess the renal function and development of kidney disease to provide strong documents in favor of decision-making.