1. Context

Staphylococcus aureus is an important human bacterial pathogen that is often found in the skin and the upper respiratory tract (1). It is known to be one of the main bacterial agents responsible for nosocomial and community infections (2). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was reported for the first time in the 1960s and spread rapidly in the 1980s (3). Over the past 45 years, hospital-related MRSA clones and community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) spread around the world. Without taking any specific control measures, the risk of occurrence of an epidemic with these strains is high (4). The first cases of CA-MRSA among children were reported in the late 1990s (5). It has been documented that this infection is more prevalent in gyms, military bases, and newborn nurseries. Moreover, it has been reported in homosexuals (6).

Carrying S. aureus pathogens in the nose increases the risk of infection, especially in the hospital setting (7), and is the most important risk factor for the transmission of this pathogen (8). Studies on the transmission of S. aureus by hospitalized patients in Madagascar showed that the prevalence of MRSA was between 4 and 13%, and the prevalence of S. aureus in outpatients was reported to be 38%, of which 15% were MRSA cases (9). Another study in Brazil revealed that the nasal carriage of S. aureus is 40.8% of which, 5.8% were MRSA (10). Medical staff members, including medical students, act as a bridge between the hospital and the community. Nasal carriage of S. aureus, especially CA-MRSA, has recently been proposed by medical students as a possible mechanism for increasing the transmission of these species between hospitals and the community (11). The prevalence of MRSA carriage among hospital staff is associated with the length of stay in the ward. Several studies on the prevalence of S. aureus nasal carriage have been published by medical students in recent decades (7, 10-12).

Several studies have also been conducted to estimate the prevalence of S. aureus in nasal carriage worldwide, including some national studies about the estimation of S. aureus nasal carriage by medical students, which shows the need for a comprehensive study for pooling their reported data in this field. In this approach, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published; however, different health-related populations have been investigated in them, except for medical students. For example, Emaneini et al. (13) carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis on nasal carriage rates of S. aureus and MRSA among Iranian healthcare workers. Their study showed the prevalence of S. aureus to be 22.7% and MRSA to be 32.8% among Iranian healthcare workers (13).

In addition, in another systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus carriage in the Asia-Pacific region from 2000 to 2016 has been investigated, which shows a prevalence of 0% to 23.5% in the general public and 0.7% to 10.4% in hospital settings (14). The pooled data in S. aureus and MRSA nasal carriage will help the world’s policymakers and health authorities to conduct more useful strategies to reduce the burden of the infection and reach the ultimate goal of healthier medical staff and students. For this purpose, the current systematic review evaluated studies and pooled their data on the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA nasal carriage among medical students.

2. Evidence Acquisition

This systematic review was performed based on the JBI methodology for a systematic review of prevalence evidence (15). In addition, the method of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was utilized in this project (16).

2.1. Review Questions

The questions of this review were as follows:

What is the prevalence of S. aureus among medical students?

What is the prevalence of MRSA among medical students?

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

Studies including medical students (preclinical or clinical) as the population were considered in this review.

2.2.2. Condition

Studies in which the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA nasal carriage were evaluated. We excluded all studies evaluating only the skin or pharyngeal samples.

2.2.3. Context

Studies performed in the medical education setting, including the hospital or university campus, were included in this review.

2.2.4. Types of Studies

All analytical-observational studies, including prospective and retrospective cohorts, as well as case-control, analytical, and descriptive cross-sectional studies, were included in this review. Moreover, studies published in English from 1967 were considered for inclusion in the current review.

2.2.5. Search Strategy

To find the studies (published and unpublished) on the subject, a three-stage method was used. In the first stage, the PubMed database was searched limitedly. In the next stage, the words were searched in the titles and abstracts, as well as the index terms used to describe the articles. The final search was conducted electronically using all detected keywords and index terms. This step was implemented on January 26, 2020, through the following databases: Medline (PubMed), Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science. The unpublished studies and gray literature such as ProQuest (dissertations and theses) and google scholar were searched, as well. In the final stage, the lists of references of all reports and studies of the review were investigated to find any other articles. The strategy by which the full search was performed in PubMed and Embase databases is provided in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

2.2.6. Study Selection

After searching, the detected citations were entered in Endnote software version X7.1.3, and the duplicate titles were omitted. Then, two independent critics reviewed and screened the titles and abstracts to make sure of the qualification of the studies concerning the inclusion criteria for the review. The full-texts of the selected studies were obtained and investigated in full detail by two reviewers, and the inclusion criteria were assessed for them. The full-text articles not having the inclusion criteria were omitted from the research. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved using sessions of discussion.

2.2.7. Assessment of Methodological Quality

Two independent reviewers critically reviewed the possible articles for the study using standard critical reviewing tools obtained from the Joanna Briggs Institute Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (17). Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by holding discussion sessions. All studies that were assessed as moderate or high level in terms of quality were included in this review.

2.2.8. Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers were asked to extract the needed information from the studies with the inclusion criteria using a modified standardized JBI data extraction tool (15). The extracted data included information on populations, sample size, study methods, and publication year, as well as the region of the study, mean age, gender, and measurement of outcomes and prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA among students of medicine. Any disagreements that arose between the critics were resolved using discussion sessions. In addition, the corresponding authors of the articles were contacted for missing data and additional information.

2.2.9. Data Synthesis

Data were pooled using statistical meta-analysis with Stata software version 16. The effect size was reported using the event rate (pooled prevalence rate). In addition, a confidence level of 95% was reached to begin the meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of the studies was calculated using the standard chi-square test, as well as the I2 test for heterogeneity. Statistical analyses were conducted by the random-effects method (18). Moreover, subgroup analyses were performed based on study designs and continents in which the study was performed. A sensitivity analysis was performed to locate heterogeneous studies. A funnel plot was generated in Stata software version 16 to assess publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Study Inclusion

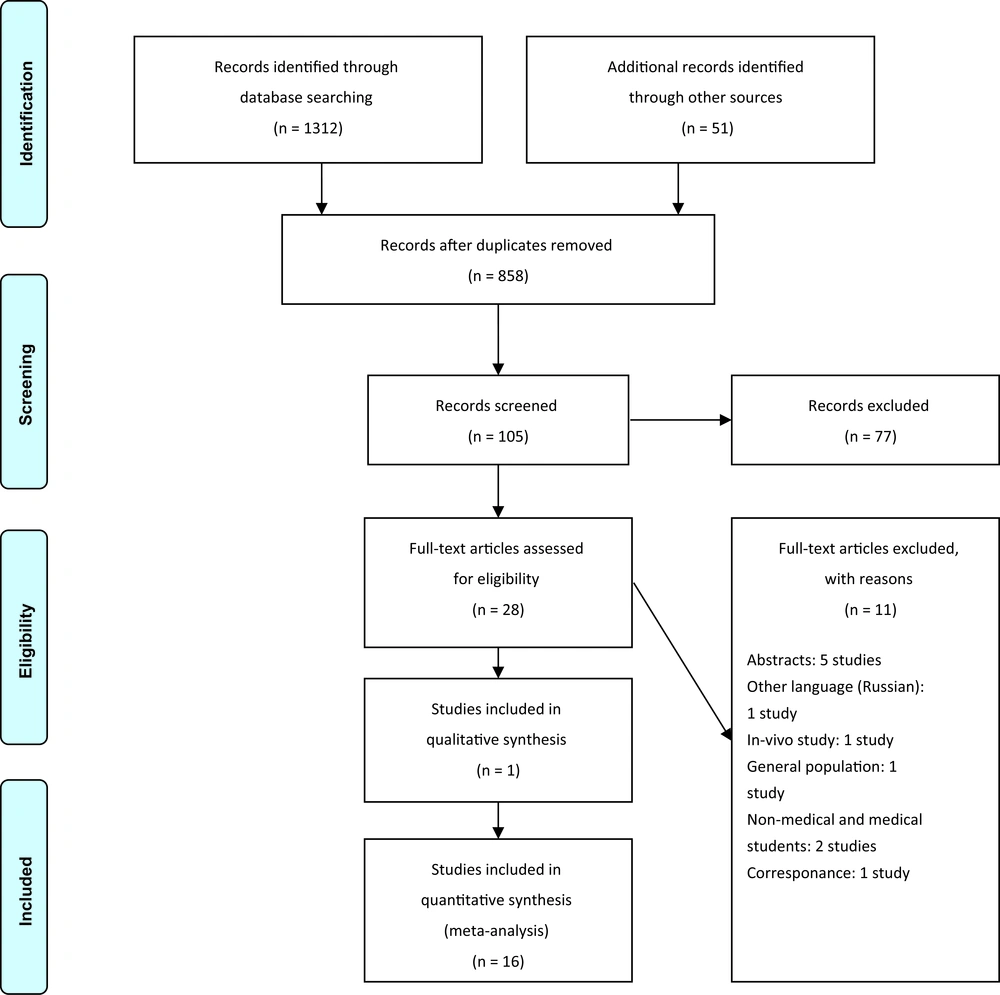

From comprehensive searching, 1,312 studies were retrieved in the electronic search and 51 studies with additional methods. Then, they were imported in Endnote X7.1.3, and duplicated records were removed. In the three steps of screening (title, abstract, and full-text), two expert reviewers selected 28 studies, of which 17 studies remained finally for the critical appraising process. You can find this selection process in PRISMA flowchart 1. Also, the reasons for excluding the articles in the full-text step are presented in Figure 1.

3.2. Methodological Quality

Totally, 16 studies were critically appraised by JBI appraisal tools for prevalence and cohort studies to evaluate the risk of biases. On that account, the quality of nine studies was assessed as high (19-27), six studies as moderate (28-33), and one study as low (34). The study with the lowest quality was excluded from this systematic review and meta-analysis (34) (Appendix 2 in Supplementary File; Table 1). Fifty percent of these studies had not appropriately sampled their populations. In most of them, they had collected participants voluntarily.

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhatta et al. (19) | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Highb |

| Ansari et al. (20) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Collazos Marin et al. (21) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Manipura et al. (22) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Hogan et al. (23) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Bettin et al. (24) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Santhosh et al. (28) | N | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderatec |

| Abroo et al. (29) | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Conceicao et al. (34) | N | N | N | N | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Lowd |

| Syafinaz et al. (25) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Zakai (26) | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | High |

| Szymanek-Majchrzak et al. (30) | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Moderate |

| Stubbs et al. (31) | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Shreyas et al. (27) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High |

| Gualdoni et al. (32) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Moderate |

| Trepanier et al. (33) | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Moderate |

| Total, % | 56.25 | 50 | 87.5 | 56.25 | 87.5 | 93.75 | 93.75 | 81.25 | 93.75 |

Critical Appraisal Results of Eligible Studiesa

3.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

Finally, after critical appraising of 16 studies, 15 studies were included. The study designs were observational, in which two studies were cohort (28, 32) and the others were cross-sectional (19, 26, 28-30, 33, 34). The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2.

| Number | Author | Year | Study Design | Country | Study Population | Sample Size | Subject Characteristics | Study Duration | Methods for Outcome Measurement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Males | Number of Females | Age | |||||||||

| 1 | Bhatta et al. (19) | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Nepal | Clinical and preclinical (first year, interns) | 200 (100 preclinical, 100 clinical) | A: 59; B: 61 | A: 41; B: 39 | A: 18 - 25; B: 22 - 30 | 5 | Nasal and pharyngeal swabs |

| 2 | Ansari et al. (20) | 2016 | Cross-sectional | Nepal | Clinical and preclinical (first year, interns) | 200 (100 preclinical, 100 clinical) | 105 | 95 | - | 1 | Nasal swabs |

| 3 | Collazos Marin et al. (21) | 2015 | Cross-sectional | Colombia | Clinical and preclinical (first year, interns) in hospital practices | 216 | 97 | 119 | 3 | Skin and nasal swabs | |

| 4 | Manipura et al. (22) | 2016 | Cross-sectional | India | Medical students (second year) | 148 | 63 | 85 | 19 - 22 | Nasal swabs | |

| 5 | Hogan et al. (23) | 2016 | Cross-sectional | Madagascar | Nonmedical students (5 different hospitals) | 1548 (685 students) | 245 | 440 | - | - | Nasal swabs |

| 6 | Bettin et al. (24) | 2012 | Cross-sectional | Colombia | Medical student | 372 | - | - | 15 - 26 (19 ± 2.21) | 6 | Nasal swabs |

| 7 | Santhosh et al. (28) | 2008 | Cohort study | India | Preclinical students | 157 | 65 | 92 | 18 - 22 | Nasal swabs | |

| 8 | Abroo et al. (29) | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Iran | Medical students (basic medical science course) | 350 | 225 | 125 | 18 - 46 | 36 | Nasal swabs |

| 9 | Conceicao et al. (34) | 2017 | Cohort study | Portugal | Nursing student | 47 | - | - | - | 48 | Nasal swabs |

| 10 | Suhaili et al. (35) | 2012 | Cross-sectional | Malaysia | Preclinical and clinical students | 209 | 81 | 128 | - | 6 | Nasal swabs |

| 11 | Zakai (26) | 2015 | Cross-sectional | Saudi Arabia | Clinical students | 150 (intern) and 32 (preclinical) | 77 | 73 | - | 6 | Nasal swabs |

| 12 | Szymanek-Majchrzak et al. (30) | 2019 | Cross-sectional | Poland | Preclinical students | 955 | 377 | 578 | 22 | 24 | Nasal swabs |

| 13 | Stubbs et al. (31) | 1994 | Cross-sectional | Australia | Preclinical and clinical | 808 | A: 124; B: 132; C: 109; D: 142; E: 30 | A: 69; B: 63; C: 60; D: 64; E: 15 | - | 1994 | Nasal swabs |

| 14 | Shreyas et al. (27) | 2017 | Cross-sectional | India | Interns | 150 | 78 | 72 | - | 2 | Nasal swabs |

| 15 | Gualdoni et al. (32) | 2012 | Cohort study | Austria | Medical students (clinical) | 79 | - | - | - | - | Nasal swabs |

| 16 | Trepanier et al. (33) | 2013 | Cross-sectional | Canada | Medical students and residents | 250 | 155 (medical stu: 68 (27.5%), resident: 87 (34.8%) | 95 (medical stu: 72.5%, resident: 65.2%) | Medical students: 21; residents: 26 | 3 | Nasal swabs |

Characteristics of Included Studies

3.4. Staphylococcus aureus Prevalence

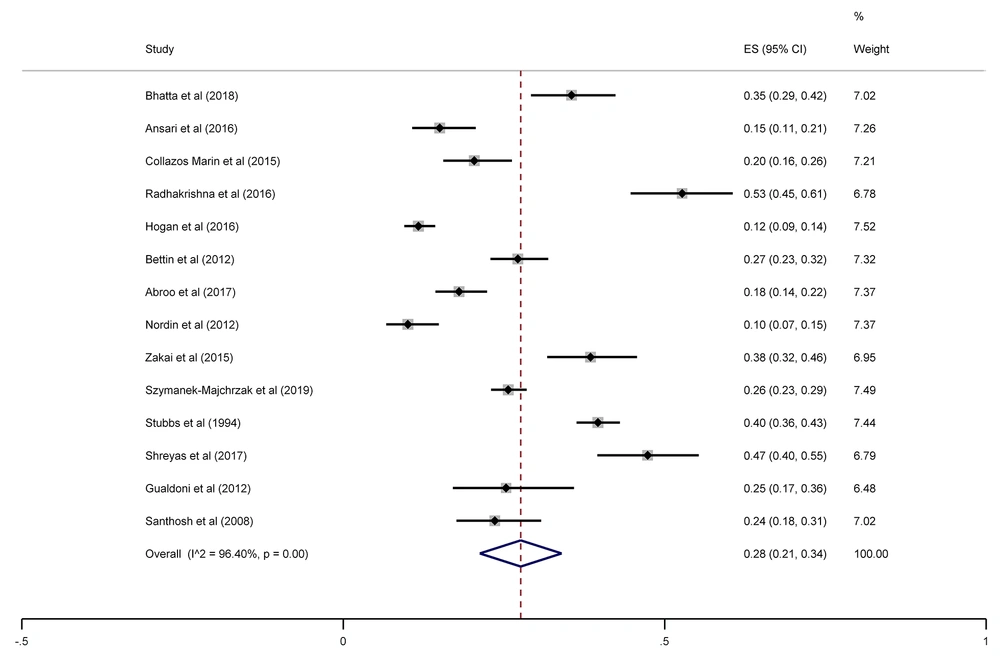

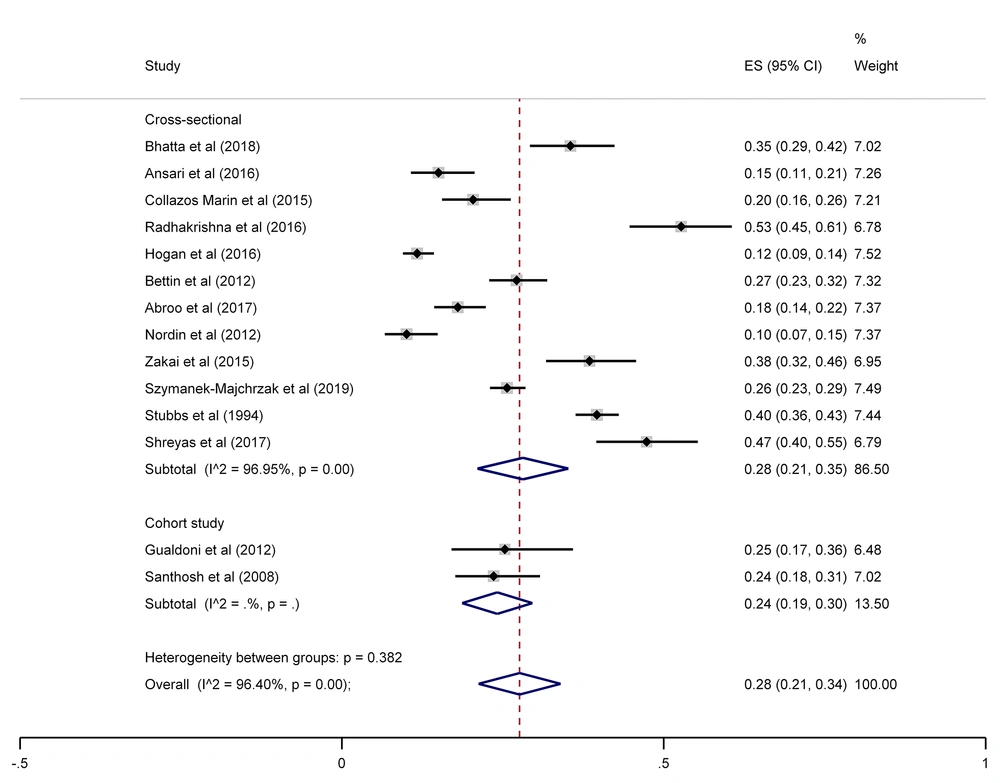

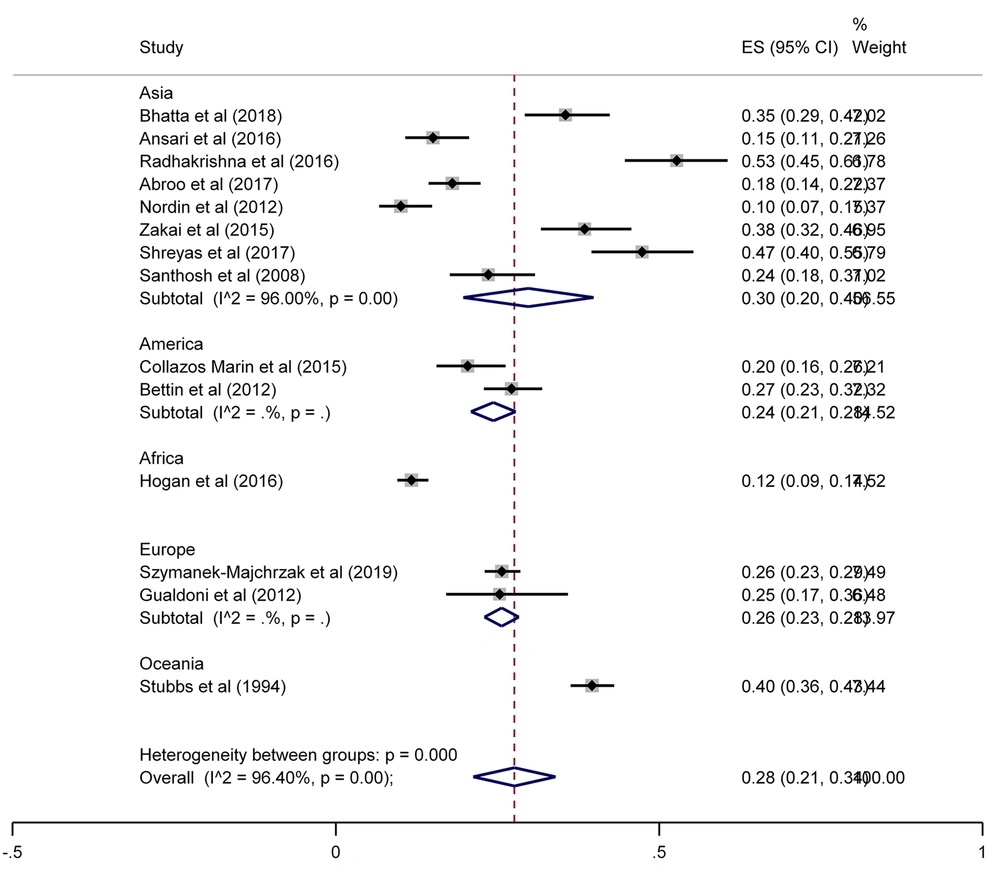

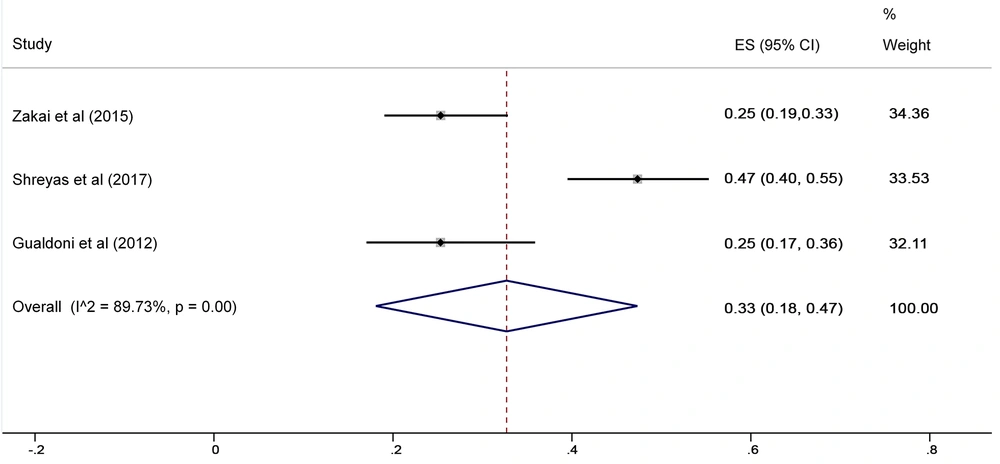

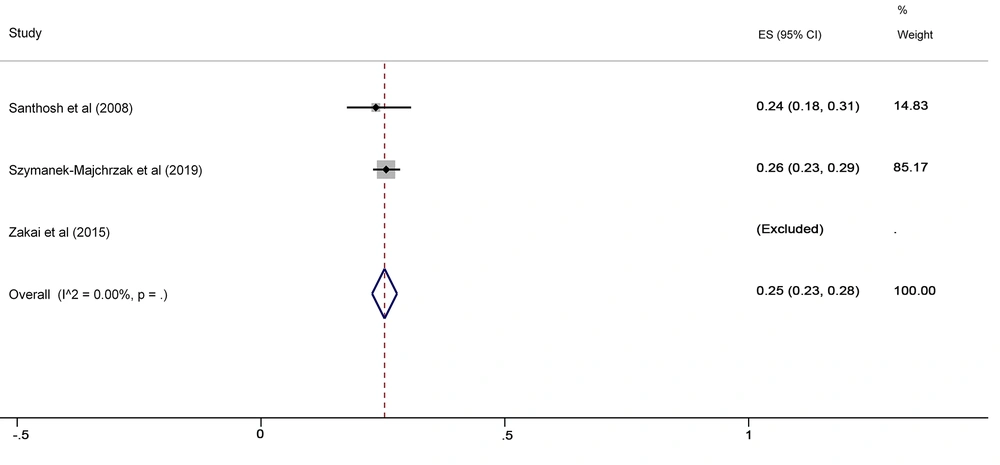

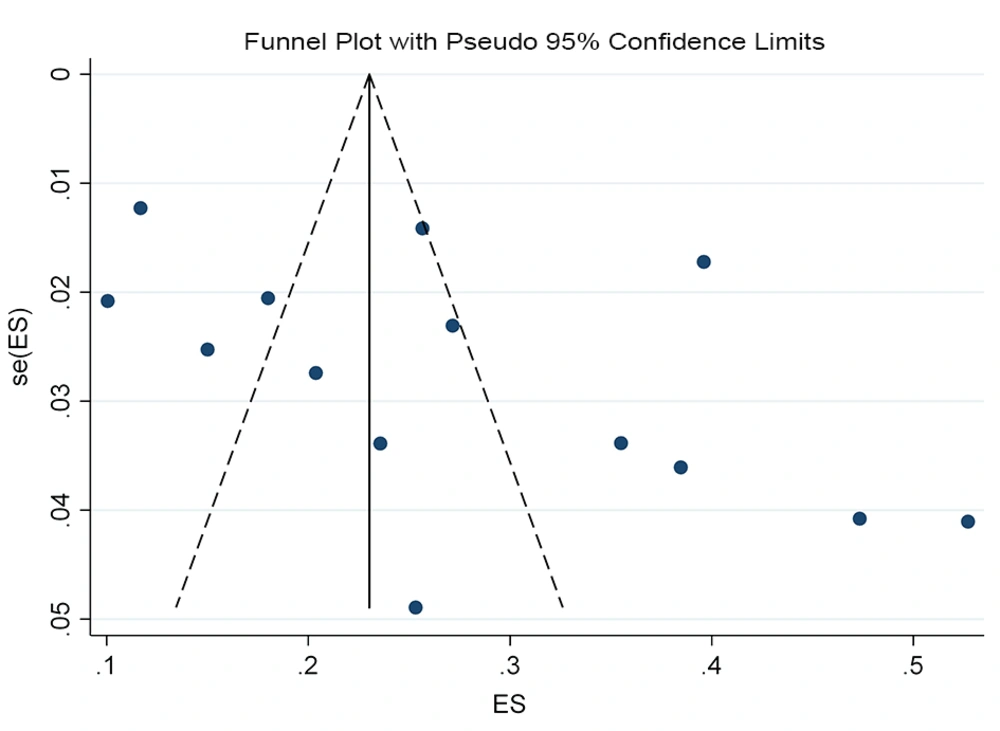

The SA prevalence was reported in 15 studies that were included in the meta-analysis. According to the results, the pooled prevalence of nasal S. aureus was 28% (prevalence: 0.028, 95% CI: 0.21 - 0.34, P < 0.001), which was varied from 10 to 72%. Moreover, the calculated heterogeneity was very high (I2: 96.40%, chi2: 360.98 (df = 14) P < 0.001) (Figure 2). Subgroup analysis based on study design was also performed in this analysis, which demonstrated 28% in cross-sectional studies and 24% in cohort studies. Furthermore, the prevalence of S. aureus among clinical students was 33% [pooled prevalence: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.18 - 0.47]; however, it was 25% among preclinical students [pooled prevalence: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.23 - 0.28] (Figure 3). In addition, subgroup analysis based on continents showed that Oceania had the highest prevalence rate of S. aureus nasal carriage (40%), and Asia (30%), Europe (26%), America (24%), and Africa (12%) had lower prevalence rates of S. aureus nasal carriage (Figure 4). Moreover, the results of the meta-analysis showed that this rate was 33% among clinical students (Figure 5) and 25% among preclinical students (Figure 6). Furthermore, to evaluate publication bias, a funnel plot was drawn. It showed that the distribution rate of studies was very high (Figure 7).

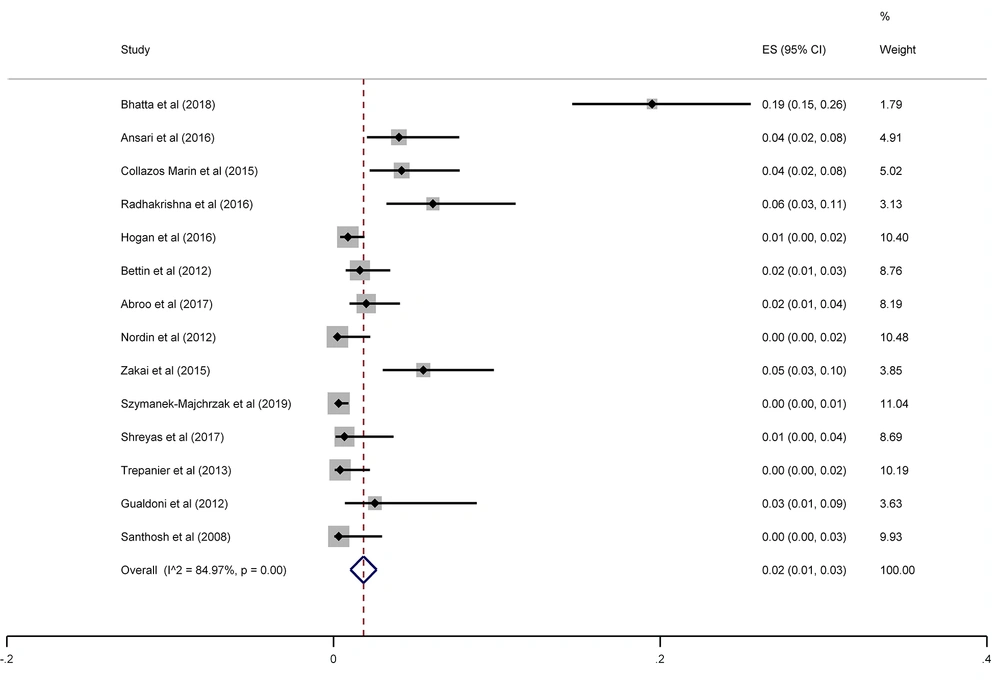

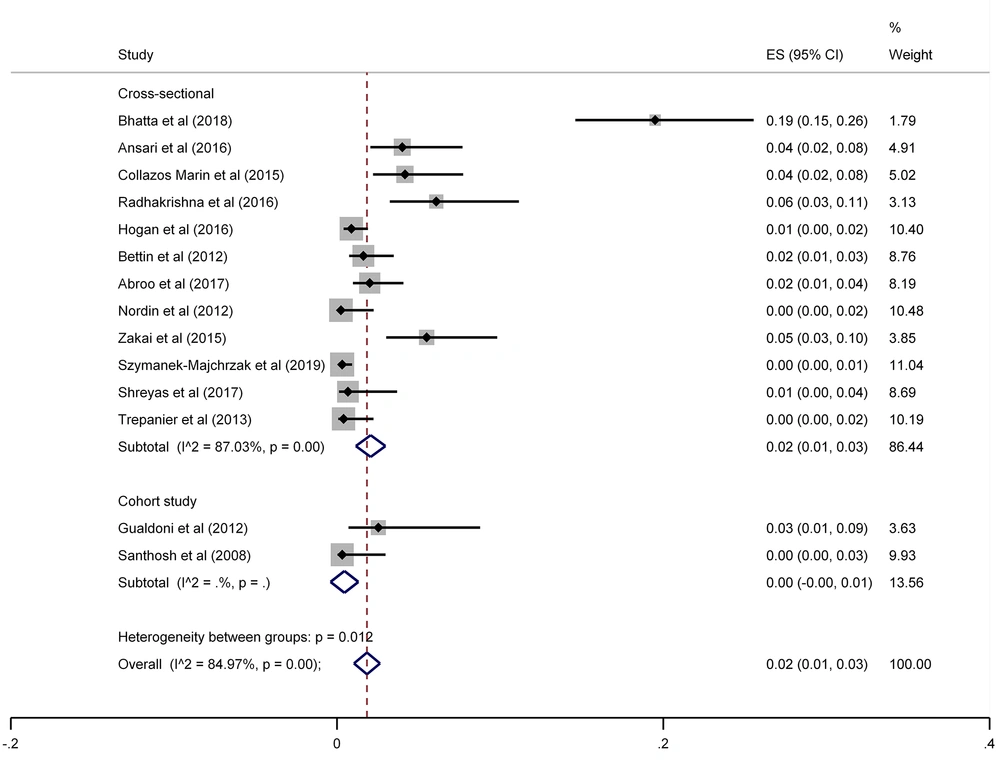

3.5. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Prevalence

The results of the meta-analysis of 15 studies that had reported nasal MRSA showed that the total prevalence among medical students was 2% (prevalence rate: 0.02, 95% CI: 0.01 - 0.03, P < 0.001) (Figure 8). This rate varied from 0 to 26% in these studies. In addition, the heterogeneity of the included studies was very high (I2: 84.97%, chi2: 86.48 (df = 14) P < 0.001). Therefore, a subgroup analysis was performed according to the study design. This meta-analysis disclosed that the pooled prevalence of MRSA was 2% and 0% in cross-sectional and cohort studies, respectively (Figure 9).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, 15 studies on S. aureus prevalence among medical students in different countries were analyzed. The prevalence rates varied widely over a range between 10 and 72%. The pooled prevalence of nasal S. aureus was 28%, which is comparable with the Kluytmans study. In this study, a mean carriage rate of 26.6% was found among Health Care Workers (HCWs) (36). However, the range of carriage rate was large (16.8 - 56.1%). This may be due to differences in the quality of sampling methods and culture techniques used in these studies (37-42). The range of carriage prevalence rate of S. aureus was higher among clinical students (33%) than in preclinical students (28%). This could be due to the increment in the possibility of exposure with S. aureus because of frequent visits to wards and clinics in the hospital setting (43).

This review incorporated 15 studies on MRSA prevalence among medical students around the world. The pooled prevalence of nasal MRSA colonization among medical students was estimated to be 2%. The estimations of the present study are more than the results of a previous review to a certain extent. That study estimated the average rate of MRSA among HCWs to be 1.8% in Europe and the United States (44). Two other reviews reported the prevalence of MRSA colonization among HCWs to be around 5% (45, 46). In both reviews, the data belonged to endemic situations and outbreaks, which was a different aspect of our review.

Despite that most of the articles were evaluated as high-quality and moderate-quality (in addition to one study evaluated as poor), the methodological assessment of the studies indicated that the quality of the articles was somehow inconsistent with the sample size and bias resolving method. Moreover, nine articles were evaluated to be of high quality. The high-quality studies showed a higher pooled MRSA involvement rate among medical students than moderate-quality studies. Possible explanations include differences in human populations, predominant strain(s), study design, and laboratory testing methods for determining resistance (47).

The major cause of classification bias was seen in the sampling location, as well as the time of evaluation of medical students (45). In most studies, sampling sites were anterior nares, and it might have led to an underestimation of the accuracy of the results of MRSA rate. The nasal samples were taken by different staff members instead of one educated person, and this could affect the reliability. Another factor was the timing of the screening test that would impact the findings of cohort studies, indicating that MRSA colonization is basically momentary (12).

Our study showed that the MRSA rate in medical students had a large variation in a range from 0% to 26%. Carriage rates among HCWs are higher than in normal populations that have no recognized risk factors (circa 0.2%) (48). This is of high importance because colonized HCWs give service to high-risk patients, including those with infections of the surgery site, neonates, and patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

In addition, it was shown that several factors can affect the design and implementation of primary studies. These factors are also effective in calculating the prevalence. It was found during this meta-analysis that cohort studies reported a lower prevalence of MRSA carriage. Although the final prevalence of MRSA carriage was reported to be circa 2%, which is similar to previous articles, a high rate of heterogeneity was seen in study populations, as well as study designs. These estimations might help find more precise estimations of the global phenomenon incidents. We might also be able to consider different factors affecting the prevalence rates.

It can be stated that the results from the present meta-analysis provide an estimation of SA and MRSA prevalence rates among medical students. This estimation comes from several performed studies among different populations. Regarding the fact that medical students are at the highest exposure risk for MRSA colonization, the prevention of MRSA colonization in this group should be considered more seriously. The results of this meta-analysis indicate that decision-makers and officials need to focus more on this public health matter and develop more accurate screening strategies for medical students in all countries.

Health care workers who are at the interface between the hospital and community may serve as specialists of cross-contamination of hospital-acquired MRSA and community-acquired MRSA. The identification of HCWs in outbreak settings colonized with MRSA is valuable in reducing the transmission and controlling the spread of MRSA. Since reducing the carrier rate of SA, especially methicillin-resistant cases, can be effective in reducing infections caused by this organism, studying and knowing the number of carriers, especially in the medical staff, can reduce nosocomial infections caused by this organism. It is suggested that the prevalence of nasal S. aureus carriage of all health professionals, including medical doctors and specialists, nurses, and other medical staff and patients at risk of infections, be evaluated in the next studies. In addition, the carrier rate of MRSA may be considered.