1. Background

Fungi are heterotrophic organisms present in the environment or in the form of normal flora in humans and animals (1, 2). Currently, various fungal species (spp.) cause life-threatening infections in immunocompromised patients, whose population is on a growing trend given the increase in cancer, AIDS, and organ transplantation cases (3). Aspergillosis consists of an extensive range of pulmonary diseases, such as invasive aspergillosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, and type I respiratory hypersensitivity reactions (4). Among Aspergillus spp., Aspergillus flavus is the most common isolate in the environment (5). Alternaria spp. are other airborne fungal agents with different prevalence rates (6). Alternaria alternata is one of the most significant filamentous fungi leading to allergic reactions, especially asthma (7). Alternaria spp. can produce a few toxins, including alternariol and alternariol monomethyl ether (8). Verticillium spp. are invasive fungal pathogens affecting more than 400 plant species, including important ornamental, horticultural, agronomical, and woody plants (9).

The microbicidal effect of ultraviolet (UV) light is a well-established finding. This light has been used to eliminate contaminations in hospitals, the pharmaceutical industry, public buildings, water treatment facilities, fresh food supplies, and agricultural products (10, 11). Ultraviolet ray is divided into the three groups of UVA (320 - 400 nm), UVB (280 - 320 nm), and UVC (200 - 280 nm) based on wavelength (10, 12, 13). Among these types, the UVC ray has the shortest wavelength and the highest energy; as a result, it can induce great effects on spores (14, 15). UV germicidal irradiation is a well-known method for inactivating a significant number of microorganisms and has wide application for sterilization. However, this method is accompanied by mutagenic effects, morphological changes, and different mycotoxin production patterns (16, 17).

2. Objectives

The present study was performed to examine the effect of UVC on the antifungal susceptibility pattern of itraconazole (ICZ), voriconazole (VCZ), fluconazole (FCZ), and amphotericin B (AMB) against filamentous environmental fungi. Changes in the morphological features of the resistant strains following UVC irradiation were also investigated using scanning electron microscopy.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Collection and Initial Identification of Isolates

Surface swab specimens were collected from predefined surfaces (i.e., lamp switch, lamp, entrance handle, fountain guard, fountain door [inside], building floor, and elevator) using premoistened cotton swabs and transferred to a laboratory with a gamma source. The specimens were immediately inoculated on plates that contained Sabouraud dextrose agar medium (SDA, Merck, Germany) with chloramphenicol (to prevent bacterial growth) at 25°C for at least 7 days. After recording the colony, the colonies grown were inoculated onto a separate potato dextrose agar (PDA; Merck, Germany) medium. The initial identification of the isolated filamentous fungi was performed. All the isolates were stored in Tryptic soy broth (TSB; Merck, Germany) at -70°C for further evaluation.

3.2. Ultraviolet Irradiations

After growth on PDA at 25°C, the conidial suspensions of the fungal strains were prepared. The cell density of the suspensions was adjusted to 0.4 - 2.5 × 104 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL, and 100 µL of the suspensions were cultured on medium per plate. The open plates were irradiated twice within a 10-minute time by a UV lamp that was oriented at a distance of 40 cm from the radiation source in a sterile condition. The irradiation was performed using UVC (Power 6 W, Japan) at a wavelength of 254 nm for three different time points, including 0 (control group), 10, and 20 min. The plates were then incubated at 25°C for 5 - 7 days and subjected to regular examination. Then, the number of fungal colonies was recorded (18).

3.3. In-Vitro Antifungal Susceptibilities Testing Before and After Ultraviolet Radiation

The antifungal susceptibility testing of the fungal species to ICZ, VCZ, FCZ, and AMB was performed according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)-M38-3rd edition for filamentous fungi (19). All the antifungal agents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (USA). Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) was also used as a quality control strain. All the tests were performed in duplicate.

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (AIS2100, Seron Technology, South Korea) was used to observe morphological changes in Aspergillus spp. The strain was prepared by cutting the agar and fixing it for a minimum of 3 h in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (100 mM phosphate buffer solution, pH = 7.2) and then 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide for 1 h. The agar blocks were dehydrated using a graded ethanol sequence (30%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%; each stage was applied twice for 15 min) and ethanol: isoamyl acetate (3:1, 1:1, 1:3, and 100% isoamyl acetate twice for 30 min). A critical point dryer (Sc7620, Emitech, England) was used with liquid CO2 to dry the agar blocks. Furthermore, a gold coater was applied to coat the agar blocks for 5 min. The coated samples were visualized at an acceleration voltage of 9 kV (20).

4. Results

4.1. Initial Identification of Isolates

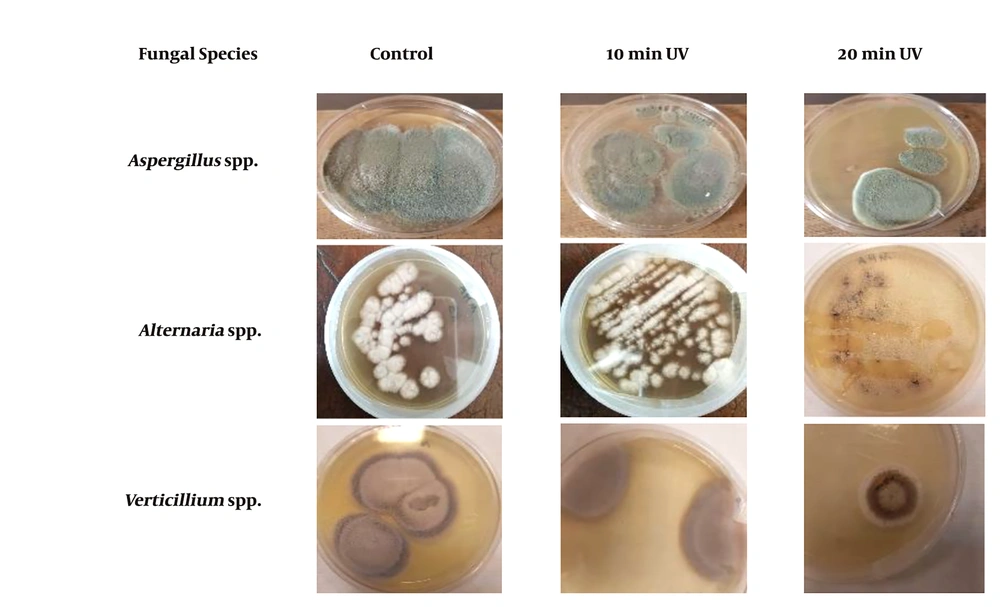

After growth of the colonies onto PDA, the identification of the isolated filamentous fungi was performed according to their macroscopic and microscopic morphological characteristics (Figure 1).

4.2. Effect of Ultraviolet C irradiation on Fungal Strains

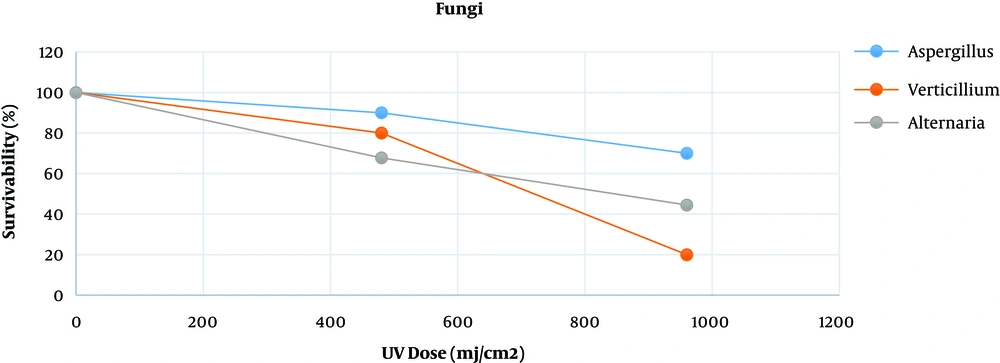

Table 1 presents the survival rates of Aspergillus spp., Verticillium spp., and Alternaria spp. exposed to various doses of UV lamp (power lamp 6W, Philips brand made in Poland; intensity: 0.8 mJ/cm2.s, length: 21.21 cm, lamp radiative power: 1.7 W, wavelength: 254 nm, distant between UV lamp and plates: 20 cm). The following formula was used to obtain the dose (16, 21).

Dose for UV (mJ/cm2) = Irradiance (mW/cm2) × time per second

| Exposure Time (min) | UV Dose (mj/cm2) | Aspergillus spp. | Verticillium spp. | Alternaria spp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 10 | 480 | 90 | 80 | 67.7 |

| 20 | 960 | 70 | 20 | 44.5 |

Figure 2 shows the survivability of the three fungal species exposed to UV radiation at different time lengths compared to that of the control group. Based on the findings, Aspergillus spp. were more resistant to radiation than Verticillium spp. and Alternaria spp. Furthermore, Verticillium spp. showed a lower survival rate than other fungi since it showed higher susceptibility after 20 min of radiation.

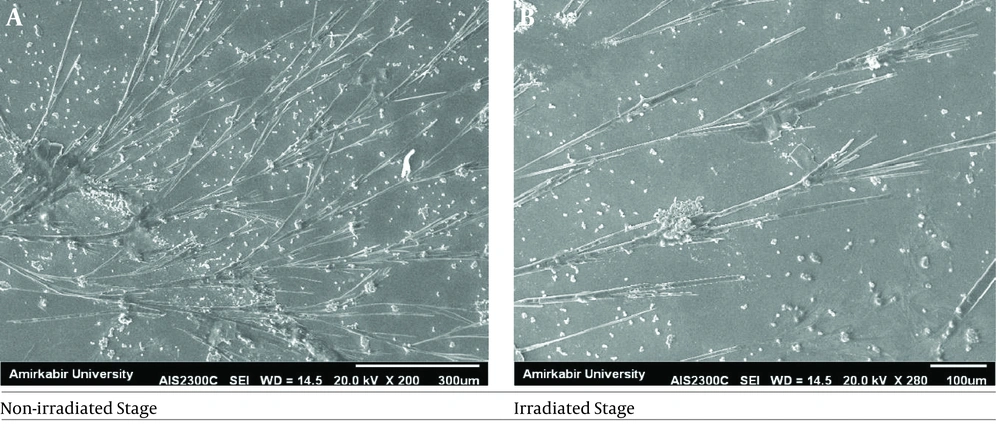

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results of the investigated antifungal agents are presented in Table 2. As the findings indicated, the MIC value of Aspergillus spp. changed after irradiation, and this species became more resistant to ICZ, VCZ, and AMB. Scanning electron microscopy was used to examine the effect of UVC irradiation on changes in the morphology of resistant Aspergillus spp. hyphae. Figure 3 illustrates the representative SEM images of Aspergillus spp. before and 20 min after UVC irradiation. The results revealed an increase in the length of the irradiated hyphae, compared to that in the non-irradiated hyphae (P < 0.05). The spore number of the non-irradiated Aspergillus spp. was huge; however, this number declined at the irradiation stage.

| Fungal Species | Antifungal Agent | Before Irradiation, Mean MIC, µg/mL | After Irradiation, Mean MIC, µg/mL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 20 min | |||

| Aspergillus spp. (n = 10) | FCZ | 8 | > 32 | >> 64 |

| ICZ | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| VCZ | 21 | > 4 | >> 8 | |

| AMB | 1 | > 2 | > 2 | |

| Alternaria spp. (n = 8) | FCZ | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| ICZ | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| VCZ | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| AMB | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Verticillium spp. (n = 5) | FCZ | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| ICZ | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| VCZ | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| AMB | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

Abbreviations: AMB, amphotericin B; FCZ, fluconazole; ICZ, itraconazole; VCZ, voriconazole; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

The collected data were analyzed in SPSS (version 19, SPSS Inc., Chicago) using analysis of variance test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

5. Discussion

The UVC ray is the most harmful and penetrating type. A positive aspect of this dangerous light is its applicability for disinfecting food contact surfaces or the storage of foodstuffs. In addition, it has deleterious effects on bone health (22) and can be used for sterilizing materials that may be otherwise impaired by excessive heat (e.g., autoclaving) spectrum (23). However, the DNA molecules in cells absorb the rays, resulting in detrimental changes for cell survival. To release free radicals (-OH), UV ray interacts with H2O molecules. These free radicals miss one or more electrons; therefore, they invade other molecules like proteins or DNA molecules to capture electrons (24, 25). Among various DNA repair systems known in fungi, nucleotide excision repair and photo reactivation are essential in repairing the damage induced by UV (26, 27). Based on evidence, UVC radiation irreversibly affects fungal colony morphology (28, 29).

In the current study, antifungal resistance was increased after irradiation (P = 0.0045); furthermore, following irradiation, Aspergillus spp. exhibited higher MIC, but the number of colony-forming units in the growth curve was significantly decreased. According to previous studies, UVC radiation can induce important alternations in fungal molecules (e.g., melanin), enhance protein production, and increase resistance to environmental conditions (30, 31). Here, the first change observed after irradiation was alteration in the colony count and morphological features of filamentous fungi in macroscopic aspects. Such morphological modifications may be caused by UVC radiation in response to physical aggression as a result of the adaptation process, which is equally observed in yeasts (32).

The present study aimed to examine whether the resistance of fungi to antifungal agents is associated with irradiation or the duration of UVC exposure. Increased resistance to antifungals may be associated with pigmentation, which has a protective role against radiation (33). Fungal resistance to radiation may be due to several former exposures to radiation. Previously, they had been in a laboratory containing gamma radiation with a 100 mCiCs source for an indefinite period of time. The pigmentation of cell walls with melanin also makes conidia less susceptible to UV damage (34, 35). Our findings are consistent with those of an earlier study performed by Abdel Hamee et al. (16), who investigated environmental fungal samples obtained from the air of mills. They concluded that UV exposure could eradicate conidia and cause an inverse correlation between exposure duration and survival fraction of conidia (16). Pourkia et al. (36) demonstrated that 8 hours of UV irradiation was effective in reducing mycelium growth in comparison with that in the control samples on Pleurotus florida. Garmon et al. (37) found the UV radiated by pulsed xenon lights reduced C. auris infection on stainless steel coupons.

Azole resistance in clinical Aspergillus spp. is significant, and in-vitro VCZ and ICZ resistance has been reported recently (38). The results of antifungal susceptibility testing revealed that the MIC of Aspergillus spp. altered significantly after UV radiation. This MIC elevation was directly associated to the duration of exposure for FCZ and VCZ. However, sensitivity to AMB did not change too much, and there was no significant difference between the Aspergillus spp. isolates exposed for 10 min and those exposed for 20 min regarding the MIC value of AMB. Similar to Aspergillus isolates, no alternation was recorded in the MIC of ICZ against Alternaria spp. after UV irradiation. However, in contrast to Aspergillus isolates, UV irradiation could not affect the MIC of AMB against Alternaria spp. These findings are in contradiction with the results of a previous study on the effectiveness of UV radiation on the drug susceptibility of Rhizopus spp., where after 10 sec of UV exposure, the MICs of FCZ (initial MIC = 16-64 µg/mL), ICZ (initial MIC = 4 - 8 µg/mL), and AMB (initial MIC = 0.5 - 2 µg/mL) decreased to less than 0.03125 µg/mL (CLSI guidelines; M38-P) (39).

In another study, the results of antifungal susceptibility testing of 12 Candida isolates to FCZ, ICZ, and AMB were reported before and after UV irradiation (CLSI guidelines (M27-A) (40). The results revealed a decrease in the MICs of FCZ, ICZ, and AMB after 10 sec of UV irradiation (40). It seems that the inconsistency of our results with previous studies may be related to the shorter duration of UV irradiation. As previously reported by Abdel Hameed et al. (16), some fungal agents may induce higher resistance to chemical and physical attacks after irradiation. Therefore, they may have a significant influence on pathogenesis. According to SEM analysis, an alternation was observed in the length of Aspergillus spp. hypha following irradiation (P < 0.05). These findings are comparable with those obtained by Abdel Hameed et al. (16), who found morphologically distinct mutants of Microsporon gypseum after UV radiation. Byun et al. (41) revealed a change in the morphology of A. flavus and A. parasiticus spores after UVC irradiation by SEM analysis.

5.1. Conclusions

Our results showed that UVC radiation could alter the antifungal susceptibility patterns of Aspergillus spp. The MICs of this species increased after radiation; consequently, it can cause systemic infections in lab technicians who are exposed to relatively high doses of radiation. The results of the SEM analysis also revealed some morphological changes in Aspergillus spp.