1. Background

Many bacteria can cause urinary tract infections. Among them, Escherichia coli is the most common agent that can cause infections at different ages. Studies in different communities have shown that Gram-negative bacilli, especially E. coli, cause more than 80 - 90% of infections (1, 2). A group of researchers has emphasized that the type of E. coli phylogenetic group plays an important role in their pathogenicity (3-5). In 2000, Clermont et al., using triplex PCR and amplification of three genetic markers, TspE4.C2, chuA, and yjaA, classified extracellular E. coli strains into four groups: B2, B1, A, and D. These different isolates were separated from different sources (6). In 2013, Clermont et al. added a new arpA gene to the previous three genes to design a quadruple polymerase reaction that had greater resolution than the previous method. In this method, E. coli isolates were divided into eight phylogenetic groups B2, B1, A, D, F, E, C, and clade I (7). These phylogroups are distinct in terms of characteristics such as patterns of antibiotic resistance, virulence genes, use of sugars, and environmental characteristics (8, 9). Outpatient pathogenic strains are mainly in group B2 and to a lesser extent in group D, while commensal strains belong to groups 1B and A (4, 10, 11).

Today, one of the most important obstacles to the control and treatment of infectious diseases is the resistance of pathogenic bacteria to various antibiotics. Bacteria use different strategies to survive the harmful effects of antibiotics. Some microorganisms are inherently resistant, and others are resistant to other organisms through the mechanisms of resistance gene release. These antibiotic resistance genes are transmitted through plasmids, transposons, and integrons (12-14).

Genes resistant to tetracycline (tetA, tetB), fluoroquinolones (qnr), sulfonamides (sul), ampicillin (CITM), and cotrimoxazole (slu, dfrA) have been observed in recent decades in E. coli isolates that perform different functions (15, 16). Tetracycline resistance can be created by acquiring the tet gene. Besides, tetA and tetB genes reduce the accumulation of antibiotics within the bacterium by encoding efflux pumps, and the isolation and detection of this dozen have been reported to be higher than other tetracycline resistance genes (17, 18). Antunes et al. showed that the most important genes that make cotrimoxazole resistance (sulfonamide group) are the sul1, sul2, and sul3 genes. The sul genes are involved in the first stage of folic acid synthesis, and dfrA genes are involved in the second stage of folic acid synthesis and induce resistance to sulfonamides (19).

The quinolone resistance is due to a mutation in the DNA gyrase subunit, and the qnr resistance genes are plasmid-dependent quinolone resistance factors that inhibit the inhibitory effect of these antibiotics on DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV cause rapid spread of resistance in Enterobacteriaceae bacteria due to their location on different integrons (20, 21). In recent years, differences in the prevalence of resistance to antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in phylogenetic groups have been of great importance. Various reports have shown that the prevalence of distribution of antibiotic susceptibility and resistance profiles, as well as drug resistance genes, varies in the phylogenetic groups of uropathogenic E. coli (4, 22-25).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine the phylogenetic groups and genes of antibiotic resistance, including tetA, tetB, sul1, sul2, dfrA1, CITM, and qnr genes in E. coli species isolated from patients with urinary tract infections using the multiplex PCR method in Yasuj (Southwest Iran).

3. Methods

This study was performed on 129 E. coli isolates collected from patients with UTIs who were referred to medical diagnostic laboratories and Imam Sajjad and Shahid Beheshti hospitals in Yasuj between July and October 2017. The population of the study included outpatients with UTIs referring to medical labs for urine culture; the growth of E. coli was considered a positive result. Exclusion criteria were having an indwelling urinary catheter, being pregnant, having genitourinary abnormalities, and antibiotic therapy within the last two weeks. After collection, urine samples were cultured on MacConkey and eosin methylene blue agar (EMB) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Then, bacteria were identified using routine biochemical tests such as methyl red (MR), Voges-Proskauer (VP), Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) agar, indole production, and Simmons’ citrate agar (Merck Germany). Isolated E. coli strains were stored in Trypticase soy broth (TSB), with sterile glycerol at -20°C (1).

3.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

The susceptibility of E. coli isolates to the antibiotics cefotaxime (30 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), cotrimoxazole (25 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (30 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), and ceftizoxime (30 μg) (BD-BBL Company, American) was assessed using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method as per the CLSI and clinical standards. To control the quality of the disks, E. coli ATCC 25922 was used (1).

3.2. DNA Extraction and Phylogenetic Grouping and Antibiotic Resistance Genes

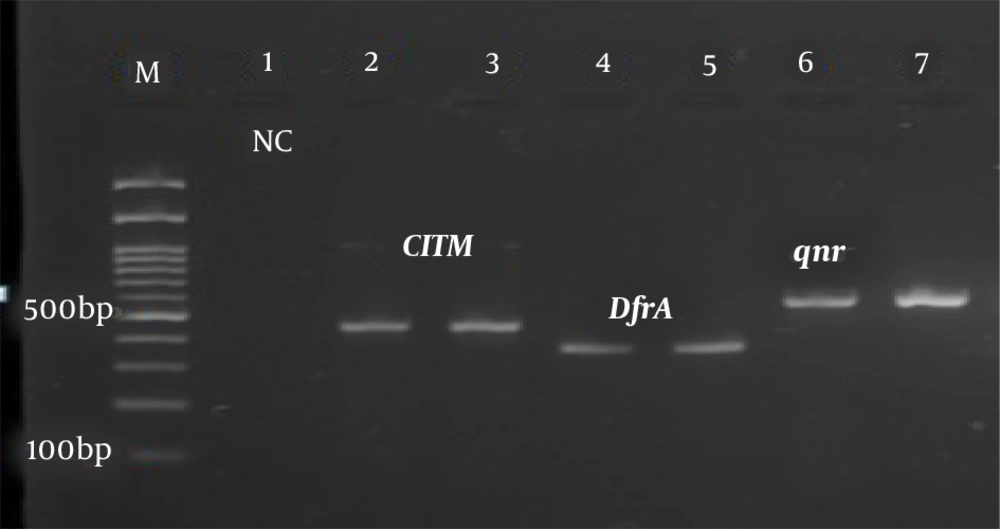

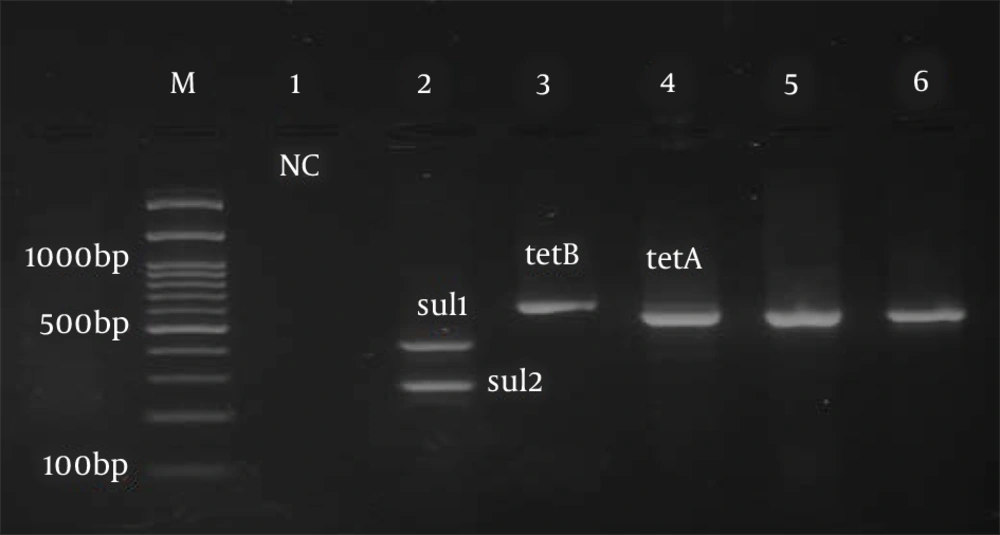

After the final diagnosis, DNA extraction from bacteria was performed by the boiling method. Briefly, several loops of bacteria (24 h) were boiled in a microtube containing sterile distilled water for 10 min at 100°C and then centrifuged. The supernatant was kept as template DNA for PCR (1). The Quadruplex-PCR method was performed using primers described by Clermont et al., to identify uropathogenic E. coli phylogenetic groups (7). Table 1 shows the primers used to detect drug resistance genes tetA, tetB, sul1, sul2, qnr, CITM, and dfrA in uropathogenic strains of E. coli. In this test, antibiotic-resistant isolates were amplified, and band formation of tetA, tetB, slu1, slu2, CITM, dfrA, and qnr genes against molecular markers confirmed the presence of these genes in the resistant isolates as positive controls from the vial. The PCR without DNA samples in which the same volume of distilled water was added, instead of DNA, was used as a negative control.

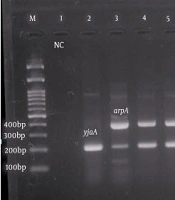

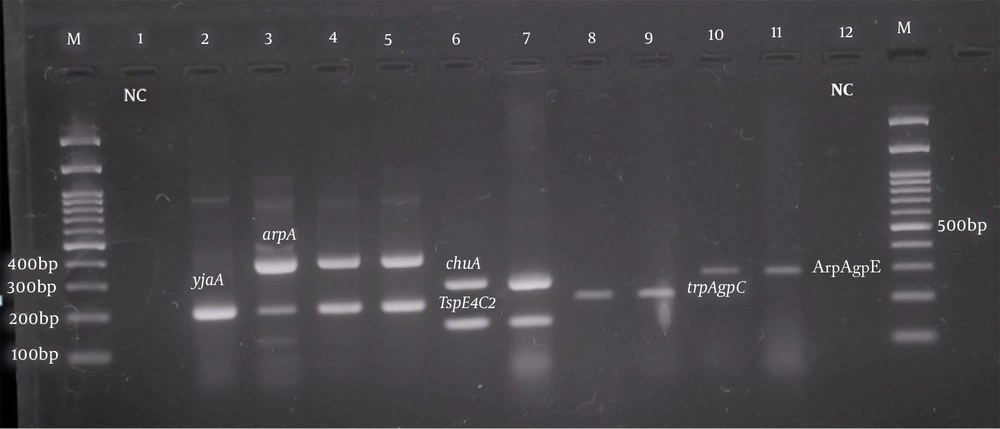

The PCR temperature program for the detection of phylogenetic groups and antibiotic resistance genes was as follows: A cycle of 95°C for 5 min, 30 cycles including 94°C denaturation for one minute, the binding temperature of the primers for phylogenetic groups of 59°C for 20 s (Figure 1), the binding temperature of the primers to the template DNA for the studied resistance genes (Table 1), amplification at 72°C for 90 s, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min (Figures 2 and 3). Electrophoresis of PCR products was performed on a 2% agarose gel with DNA safe stain dye solution in the presence of a 100 bp marker (Pishgam, Iran) and 90-volt constant voltage for 60 min. The gel was examined with a UV Transilluminator (Major Science, Taiwan).

| Antimicrobial agent/Resistance gene | Sequence | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline | (15) | |||

| tetA F | GGTTCACTCGAACGACGTCA | 58 | 577 | |

| tetA R | CTGTCCGACAAGTTGCATGA | |||

| tet B F | CCTCAGCTTCTCAACGCGTG | 58 | 634 | |

| tet B R | GCACCTTGCTGATGACTCTT | |||

| Trimethoprim | ||||

| dfra F | GGAGTGCCAAAGGTGAACAGC | 63 | 367 | |

| dfra R | GAGGCGAAGTCTTGGGTAAAAAC | |||

| Beta-lactams | ||||

| CITM F | TGGCCAGAACTGACAGGCAAA | 63 | 462 | |

| CITM R | TTTCTCCTGAACGTGGCTGGC | |||

| Quinolones | ||||

| qnr F | GGGTATGGATATTATTGATAAAG | 59 | 670 | |

| qnr R | CTAATCCGGCAGCACTATTTA | |||

| Sulfonamide | (26) | |||

| sul1 F | CGGCGTGGGCTACCTGAACG | 63 | 433 | |

| sul1 R | GCCGATCGCGTGAAGTTCCG | |||

| sul2 F | GCGCTCAAGGCAGATGGCATT | 63 | 293 | |

| sul2 R | GGGTTTGATACCGGCACCCGT |

Sequence of Primers of Antibiotic Resistance Genes Used for Polymerase Chain Reaction

Phylogenetic analysis of pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Left to right: 100 bp marker, well number one as a negative control, well numbers 2, 3, 4, and 5 with yjaA (211 bp) and arpA (400 bp), well numbers 6 and 7 with chuA (288 bp) and TspE4.C2 (152 bp), well numbers 8 and 9 with trpAgp C (219 bp), and well numbers 10 and 11 with ArpAgpE (301 bp) genes.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test with SPSS software (version 18.0). The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

The prevalence of urinary tract infections was higher in females of all age groups. In this study, 99 (76.7%) of the studied samples were related to women and 30 (23.3%) to men. The phylogenetic groups of the collected E. coli isolates were determined using the method mentioned by Clermont et al. (7). The PCR results showed that 36.4% of the strains belonged to group B2, 20.2% to the unknown group, 13.2% to group C, 10.1% to group Clade I, 9.3% to group D, 7.8% to group E, 3.1% to group A, and phylogenetic groups B1 and F were not observed among the strains studied in this study (0%). Also, the distributions of tetA, tetB, sul1, sul2, dfrA1, CITM, and qnr antibiotic resistance genes were 59.7, 66.7, 69, 62, 23.3, and 30.2%, respectively. The prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes among phylogenetic groups is shown in Table 2. In the statistical analysis based on Fisher's exact test, no significant relationship was observed between gender and phylogenetic groups (Table 3). In our study, the prevalence of antibiotic resistance and antibiotic-resistant genes was higher in the isolates of phylogenetic group B2 than in other phylogenetic groups (Table 4).

| Antibiotic resistance genes | B2 (n = 47) | D (n = 12) | C (n = 17) | E (n = 10) | U (n = 26) | Clade I (n = 13) | A (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tetA | 24 (51.7) | 7 (58.3) | 11 (64.7) | 7 (70) | 16 (61.5) | 10 (76.9) | 2 (50) |

| tetB | 32 (68) | 10 (83.3) | 12 (70.5) | 7 (70) | 15 (57.6) | 10 (76.9) | 0 (0) |

| sul1 | 35 (74.4) | 10 (83.3) | 11 (64.7) | 3 (30) | 18 (69.23) | 8 (61.5) | 4 (100) |

| sul2 | 25 (53) | 11 (91.6) | 12 (70.5) | 5 (50) | 14 (53.8) | 10 (76.9) | 3 (75) |

| dfrA | 12 (25.5) | 2 (16.6) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (20) | 2 (7.69) | 6 (46) | 1 (25) |

| CITM | 16 (34) | 3 (25) | 5 (29.4) | 3 (30) | 9 (34.6) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) |

| qnr | 11 (23.4) | 2 (16.6) | 3 (17.6) | 1 (10) | 7 (26.9) | 2 (15.3) | 0 (0) |

| qnr,sul1 | 7 (14.8) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (15.38) | 2 (15.3) | 0 (0) |

| sul1, sul2 | 17 (36.17) | 9 (75) | 9 (52.9) | 1 (10) | 8 (30.7) | 5 (38.4) | 3 (75) |

| tetA, tetB | 18 (38.2) | 5 (41.6) | 11 (64.7) | 5 (50) | 12 (46) | 9 (69.2) | 1 (25) |

| sul1, sul2, tetA, tetB | 7 (14.8) | 4 (33.3) | 6 (35.2) | 0 | 3 (11.5) | 4 (30.7) | 0 (0) |

| qnr,sul1, dfrA | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Distribution of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Relation to Phylogenetic Groups in Escherichia colia

| Sex | B2 (n = 47) | C (n = 17) | D (n = 12) | A (n = 4) | E (n = 10) | Clade I (n = 13) | Unknown (n = 26) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 11 (23.4) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (26.9) | 0.83 |

| Female | 36 (76.6) | 12 (70.6) | 10 (83.3) | 4 (3.1) | 7 (70.0) | 11 (84.6) | 19 (73.1) |

Distribution of Phylogenetic Groups Based on Gender a

| Phylogenetic groupe | Ampicillin | Tetracycline | Nalidixic Acid | Co-Trimoxazole | Ciprofloxacin | Cefotaxime | Ceftriaxone | Aztreonam | Ceftezoxim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2 (n = 47) | 36 (76.5) | 28 (59.5) | 32 (68) | 33 (70) | 25 (53) | 22 (46.8) | 22 (46.8) | 28 (59.5) | 30 (63.8) |

| C (n = 17) | 12 (70.5) | 10 (58.8) | 9 (52.9) | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41) | 7 (41) | 8 (47) | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47) |

| D (n = 12) | 11 (91.6) | 10 (83.3) | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.6) | 8 (66.6) | 7 (58.3) | 7 (58.3) | 9 (75) | 4 (33.3) |

| E (n = 10) | 8 (80) | 4 (40) | 5 (50) | 3 (30) | 3 (30) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 5 (50) | 2 (20) |

| Clade I (n = 13) | 11 (84.6) | 10 (76.9) | 5 (38.4) | 9 (69.2) | 6 (46) | 7 (53.8) | 8 (61.5) | 9 (69.2) | 10 (76.9) |

| Unknowen (n = 26) | 24 (92.3) | 20 (76.9) | 10 (38.4) | 17 (65) | 14 (53.8) | 15 (57.6) | 15 (57.6) | 22 (84.6) | 20 (76.9) |

| A (n = 4) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) |

| Total | 104 (80.6) | 85 (65.8) | 67 (51.95) | 82 (63.5) | 65 (50.3) | 63 (48.8) | 65 (50.3) | 85 (65.8) | 76 (58.9) |

| P-value | 0.340 | 0.406 | 0.048 b | 0.664 | 0.491 | 0.003 b | 0.615 | 0.120 | 0.026 b |

Frequency of Antibiotic Resistance Among Phylogenetic Groups of Uropathogenic Escherichia colia

We found a significant relationship between the E. coli phylogenetic groups of ceftizoxime (P = 0.026), cefotaxime (P = 0.003), and nalidixic acid (P = 0.048) antibiotics. Also, in this study, no significant relationship was observed between E. coli phylogenetic groups and antibiotic resistance genes. In the present study, we found a significant relationship between the presence of genes encoding antibiotic resistance, including qnr gene and resistance to nalidixic acid (P = 0.016) and ciprofloxacin (P = 0.034), the gene encoding sul1 resistance, and resistance to cefotaxime (P = 0.003), ceftriaxone (P = 0.011), cotrimoxazole (P = 0.003), and ceftizoxime (P = 0.011), the presence of tetA resistance gene and resistance to tetracycline (P = 0.006), ampicillin (P = 0.001), aztreonam (P = 0.005), and ciprofloxacin (P = 0.001) antibiotics, the presence of tetB encoding gene and tetracycline resistance (P = 0.037), as well as the presence of dfrA1 coding gene and ceftriaxone resistance (P = 0.041) (Table 5).

| Antibiotic Resistance Genes | Ampicillin | Tetracycline | Nalidixic Acid | Co-Trimoxazole | Ciprofloxacin | Cefotaxim | Cefteriaxon | Azteronam | Ceftezoxim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tetA | 69 (89.6) | 55 (71.4) | 37 (48.1) | 50 (64.9) | 34 (44.2) | 35 (45.5) | 33 (42.5) | 52 (67.5) | 37 (48.1) |

| P-value | 0.001 b | 0.006 b | 0.902 | 0.290 | 0.013 b | 0.402 | 0.597 | 0.005 b | 0.566 |

| tetB | 73 (84.9) | 57 (66.3) | 47 (54.7) | 62 (71.2) | 32 (37.2) | 43 (50) | 43 (50) | 51 (53.9) | 40 (46.5) |

| P-value | 0.072 | 0.037 b | 0.170 | 0.001 b | 0.964 | 0.159 | 0.089 | 0.426 | 0.820 |

| sul1 | 73 (82) | 52 (58.4) | 48 (53.9) | 61 (68.5) | 38 (42.7) | 46 (51.7) | 46 (51.7) | 52 (58.4) | 47 (52.8) |

| P-value | 0.201 | 0.561 | 0.203 | 0.003 b | 0.069 | 0.003 b | 0.011 b | 0.625 | 0.011 b |

| sul2 | 62 (77.5) | 54 (67.5) | 39 (48.8) | 56 (70) | 27 (33.8) | 33 (41.3) | 31 (38.8) | 44 (55) | 37 (46.3) |

| P-value | 0.111 | 0.106 | 0.160 | 0.018 b | 0.309 | 0.440 | 0.394 | 0.852 | 0.820 |

| qnr | 22 (84.6) | 14 (53.8) | 18 (69.2) | 17 (65.4) | 14 (53.8) | 15 (57.7) | 16 (61.5) | 18 (69.2) | 16 (61.5) |

| P-value | 0.638 | 0.696 | 0.016 b | 0.557 | 0.034 b | 0.299 | 0.111 | 0.247 | 0.100 |

| CITM | 31 (79.5) | 25 (64.1) | 14 (35.9) | 21 (53.8) | 13 (33.3) | 13 (33.3) | 12 (30.8) | 18 (46.2) | 15 (38.5) |

| P-value | 0.146 | 0.201 | 0.084 | 0.840 | 0.259 | 0.146 | 0.157 | 0.300 | 0.288 |

| dfrA | 24 (80) | 18 (60) | 19 (63.3) | 18 (60) | 14 (46.7) | 11 (36.7) | 7 (23.3) | 18 (60) | 17 (56.7) |

| P-value | 0.638 | 0.696 | 0.016 b | 0.557 | 0.034 b | 0.299 | 0.111 | 0.247 | 0.100 |

Distribution of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Antibiotic Resistance Patterns of Escherichia coli Strains Causing Urinary Tract Infection a

5. Discussion

Various studies have shown that the patterns of antibiotic resistance and susceptibility, the number of virulence genes, as well as genes encoding antibiotic resistance in E. coli in different geographical areas are associated with specific genetic groups (4, 27, 28). Therefore, in this study, we tried to investigate the prevalence of phylogenetic groups, antibiotic resistance genes, and the distribution of these resistance genes and antibiotic resistance patterns in uropathogenic E. coli phylogenetic groups based on the new method of Clermont et al. for the first time in Yasuj (Southwest Iran). The results of several studies indicate that extraintestinal pathogenic strains mainly belong to groups B2 and D (to a lesser extent) and, also, the commensal isolates of E. coli belong to groups A and B1 (2, 10, 22). In the present study, the most common phylogenetic groups belonged to group B2 with a prevalence of 36.4%. It was followed by unknown phylogenetic (20.2%), C (13.2%), Clade I (10.1%), D (9.3%), E (7.8%), and phylogenetic group A with a prevalence of 3.1%. As expected, in the present study, the highest frequency belonged to the B2 phylogroups.

The results of our study are consistent with other studies in Iran (2, 4, 29) and other parts of the world, including Pakistan (30), Mexico (31), and South Korea (11). However, in a study conducted in Kerman (Iran), phylogroup A and in another study in Mexico on UPEC strains, phylogroups D had a higher frequency than other genetic phylogroups. This may be due to reasons such as different distributions of E. coli strains in different geographical areas (32, 33). In our study, after phylogroup B2, the most common phylogroup belonged to the unknown group, which is consistent with the studies by Iranpour et al. and Najafi et al. in Iran, with the report of a 27% unknown phylogroup (4, 34). However, in a study conducted by Ghosh et al. in India, 77% of the isolates remained unclassified, which contradicted the results of the present study (35). Clermont et al. in 2013 reported that a new quadruplex PCR method does not classify only one percent of E. coli strains into the eight phylogenetic groups. However, about 20.2% of the total E. coli isolates in our study remained unclassified.

Although the explanation for these results is indescribable, it can be said that the strains in the unknown group are the results of recombination of different phylogroups or are very rare phylogroups (7). On the other hand, in this study, phylogenetic groups B1 and F were not found in any of the E. coli isolates studied, which is consistent with the results obtained by Ghosh et al. (35). These differences in the distribution of phylogenetic groups in the present study compared to other studies could be due to differences in geographical areas, host health status, nutritional factors, patterns of antibiotic use, genetic factors, as well as differences in the anatomical area of bacterial isolation (5, 36).

The discovery of antibiotics, the production and development of new antibiotics, and the widespread use of these antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial infectious diseases have led bacteria to become more resistant to various antibiotics. Due to the increasing prevalence of resistance to antibiotics, the rapid and timely detection of resistant strains seems necessary to select appropriate treatment options and prevent the spread of resistance (24). Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antibiotics are different. Usually, the presence of genes encoding antibiotic resistance is the main cause of antibiotic resistance in bacterial strains, and the most common resistances are controlled by transmissible plasmids (14, 37).

Tetracycline-resistant strains are highly prevalent among antibiotic-resistant E. coli. Tetracycline is a bacteriostatic antibiotic that binds to ribosomes and prevents protein synthesis from lengthening. The presence of resistant genes in bacteria is associated with the acquisition of the tet gene (18, 38). Another drug that is widely used for treating urinary tract infections is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Its resistance mechanism in E. coli is due to uropathogenicity because of the structural similarity of sulfonamides to para aminobenzoic acids (PABAs), which leads to the production of folic acid. The lsu genes cause resistance to sulfonamides (39).

Quinolones and fluoroquinolones are the drugs of choice for treating urinary tract infections caused by E. coli due to their antibiotic resistance. The qnr gene causes resistance to fluoroquinolones (20, 21). Genetic markers of bacterial antibiotic resistance have often been reported in various studies. The prevalence and distribution of these genetic profiles vary depending on the country, source, and year of bacterial isolation, and antibiotic prescribing policy (15, 33, 40). In this study, we investigated the prevalence of some genes causing antibiotic resistance in 129 E. coli isolates by PCR. The prevalence rates of the resistance genes tetA, tetB, sul1, sui2, qnr, CITM, and dfrA were 59.7, 66.7, 69, 62, 20.2, 30.2, and 23.3%, respectively. The frequency of antibiotic resistance genes in the present study was close to the results of studies conducted in Iran (14, 15, 41) and other parts of the world, including Algeria (42) and Mexico (43). The high prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes may be due to the indiscriminate use of antibiotics as well as the horizontal transmission of strains containing these antibiotic resistance genes in patients with urinary tract infections.

In this study, the distribution of multidrug resistance in different E. coli phylogenetic groups showed that phylogroup B2 isolates were more resistant than the isolates of other phylogenetic groups. Past studies have shown that the prevalence of antibiotic resistance among E. coli strains is related to the B2 phylogenetic group less than to other phylogenetic groups. Although difficult to explain, different social and environmental conditions may play a role (32, 44, 45). However, our findings are consistent with some studies that have shown the most resistant isolates were in the B2 phylogroup (4, 10, 22, 25). Our study showed a significant relationship between phylogenetic groups and antibiotic resistance (P < 0.05) (Table 4). Some studies have also reported an association between phylogenetic groups and antibiotic resistance (28, 46). This indicates that the balance between antibiotic resistance and virulence factors is disturbed, and one of the two variables is increased or decreased in favor of the other, and it can be said that the strains that carry pathogenic genes are compatible with drug resistance (11).

5.1. Conclusion

Based on this study, it can be concluded that in recent years, isolates of uropathogenic E. coli have emerged that, in addition to having multiple virulence genes, have become resistant to different types of antibiotics. This study was the first report on the prevalence of phylogenetic groups, and their relationships with antibiotic resistance patterns and antibiotic resistance genes among E. coli strains causing UTIs in Yasuj (Southwestern Iran). One of the limitations of our study is the lack of study of the prevalence of virulence genes of E. coli in general uropathogens and their distribution and relationship with these phylogenetic groups. Finally, the results of our study showed that strains belonging to group B2 were most common among other phylogroups and also antibiotic resistance genes and drug-resistant isolates in this phylogroup (phylogroup B2) had a higher prevalence among patients with urinary tract infections in Yasuj (Southwestern Iran). Also, in this study, among the antibiotic resistance genes, the tetB, tetA, slu1, and slu2 genes had a higher prevalence. Understanding the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance genes and phylogenetic groups of uropathogen E. coli causing urinary tract infections can help physicians treat urinary tract infections by selecting appropriate antibiotics in this geographical area to prevent the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains.