1. Background

Dental caries is one of the most common and among costly and expensive oral diseases for treatment (1). Streptococcus mutans is the main etiologic bacterium initiating caries and expressing important virulence factors related to dental caries pathogenesis. Streptococcus mutans uses three specific glucosyltransferases (GTFs) to convert sucrose to a sticky extracellular polysaccharide (ECP) that allows them to attach to dental surfaces and form plaque (2). A large number of glucan-binding proteins are known in S. mutans, such as SpaP and GbpB and C. The spaP gene encodes the P1 protein that has a high affinity for binding to the salivary glycoprotein of S. mutans (3). Biofilm maturation is controlled by the Quorum Sensing system (QS). Streptococcus mutans also contains two density-dependent transmission systems. The QS and interspecific transmission systems are encoded by the luxS gene (4). Biofilm formation can increase bacterial antibiotic resistance and restrict the ability of the host’s inflammatory cells to engulf biofilm-surrounded organisms. Acid production by biofilm forming bacteria destroys tooth enamel, leading to hole creation and tooth decay (5).

A new approach to fight and control biofilm formation by bacteria is to use specific bacteriophages as the viruses invading and killing bacteria (6). They are ubiquitous and approximately 50 times smaller than bacteria (20 - 200 nm), enabling them to effectively penetrate into biofilm layers (7). Phages infect the target bacteria without affecting the normal flora and are naturally eliminated by the eradicating of the bacterium. One advantage of phages is that they can be easily administered either orally, intravenously, or nasally (8). There are few reports on the isolation of lytic phages of S. mutans, and there is no study on the potential effects of these phages on the expression of the genes contributing to S. mutans biofilm formation.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to isolate S. mutans bacteriophages from wastewater and assess their effects on the expression of the genes involved in biofilm formation by S. mutans.

3. Methods

3.1. Isolation and Confirmation of Streptococcus mutans

Eighty-one dental plaque samples were taken by a dentist from the patients with dental caries, referred to the dental clinic of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. To isolate S. mutans, brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Merck, Germany) and Mitis-Salivarius agar (QueLab, Canada) were used to incubate bacteria for 24 - 48 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After Gram staining, suspected S. mutans colonies were confirmed by tests such as catalase, carbohydrate fermentation, and urea hydrolysis to obtain pure cultures (9). Streptococcus mutans ATCC35866 was considered as a positive control.

3.2. PCR Identification of Streptococcus mutans Isolates

Initially, DNA of the isolated S. mutans was extracted using the method described by Hoshino et al. (10). A nanodrop device (Thermo, Lithuania) was used to determine the concentration of the obtained DNA. The oligonucleotide sequences of the primers (Metabion, Germany) used for the PCR amplification of virulence genes have been displayed in Table 1 (10-13). Amplification was carried out by applying a thermocycler (Peqlab, China), and PCR products were visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

| Target Gene | Primer Sequence (5’ → 3’) | PCR Product, bp | PCR Programs | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gtfD | F: -GGCACCACAACATTGGGAAGCTCAGTT- | 431 | 1 cycle: 95°C (5 min); 35 cycles: 94°C (45 s), 59 to 68°C (based on primers, 60 s), 72°C (60 s); 1 cycle: 72°C (5 min) | (10) |

| R: -GGAATGGCCGCTAAGTCAACAGGAT- | ||||

| gtfB | F: -AGCAATGCAGCCAATCTACAAAT- | 96 | (11) | |

| R: -ACGAACTTTGCCGTTATTGTCA- | ||||

| gtfC | F: -CTCAACCAACCGCCACTGTT- | 91 | (11) | |

| R: -GGTTTAACGTCAAAATTAGCTGTATTAG- | ||||

| spaP | F: -AACGACCGCTCTTCAGCAGATACC- | 192 | (12) | |

| R: -AGAAAGAACATCTCTAATTTCTTG- | ||||

| luxS | F: -ACTGTTCCCCTTTTGGCTGTC- | 93 | (13) | |

| R: -AACTTGCTTTGATGACTGTGGC- |

Oligonucleotide Sequences of Primers and PCR Amplification Program

3.3. Sampling, Isolation, and Purification of Bacteriophages

Raw sewage from urban wastewater of Tehran was supplied, and after overnight, 10 mL of the collected specimens was centrifuged for 10 min at 6000 g and 4°C. The supernatant was passed through a 0.22 µm filter, and 1 ml of the filtered liquid was poured into a tube containing 5 mL of BHI broth with S. mutans (106 CFU/mL) to be incubated for 24 h at 37°C while shaking (120 rpm). The tube was centrifuged again for 10 min at 6000 g (4°C), and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm filter. The filtered liquid was evaluated by the double-layer agar method, which was repeated several times to separate a single plaque. For purification of bacteriophages, the plate surface was rinsed using 4 mL of the SM buffer and incubated for 5 h while shaking. Finally, the supernatant was passed through a filter and assessed by the double-layer agar method until the isolation of pure plaques. The SM buffer with 20% glycerol was used to preserve bacteriophages. The sensitivity of the isolated phages was measured by the temperature (4°C - 70°C) and pH (3 - 10) tests. To determine bacteriophages’ hosts, the agar spot method was used for Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212, Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 6303, Streptococcus agalactiae ATCC 12386, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, and the isolated S. mutans (14).

3.4. Bacteriophage Morphology

Bacteriophage morphology was studied using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Drops of the bacteriophage were placed on a copper grid coated with carbon, stained by 2% uranyl acetate, and assessed by a Zeiss-Em10c-100k transmission electron microscope.

3.5. Inhibitory Effects of Isolated Lytic Phages on Streptococcus mutans Biofilm Formation

At first, the biofilm formation ability of S. mutans isolates was evaluated at 550 nm by the microtiter plate method. Then the inhibitory effects of isolated lytic phages on S. mutans biofilm formation were investigated. For this purpose, 100 µL of 0.5 McFarland standard S. mutans suspension in the TSB containing 2% sucrose and 50 µL phage was poured into the wells of a microtiter plate and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with CO2. After washing three times, the plate was left to dry, then stained with 1% crystal violet (Merck, Germany), and incubated at 37°C while shaking (120 rpm) for 15 min. The OD of each well was measured at 550 nm using an ELISA reader. Each test was repeated three times (15). The percentage of biofilm formation was calculated according to this formula:

In this equation, C is the mean OD of control wells, B represents the mean OD of negative controls, and T shows the mean OD of test wells (16).

3.6. Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

The biofilms formed in the microtiter plates, with or without bacteriophages (each with 3 replicates) were subjected for RNA extraction using a high-pure RNA isolation kit (Roche, Germany). The quantity and purity of the extracted RNA was measured by a Nano Drop device. Applying a cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific Revert Aid), the extracted RNA was converted to cDNA based on the manufacturer’s instructions. Each reaction tube contained 10 µL of the extracted RNA, 1 µL Hexamer primer, 2.5 µL DEPC water, 4 µL 5x standard buffer, 1 µL dNTPs, 0.5 µL RiboLock RNAase, and 1 µL M-MLV, in a total volume of 20 µL. Real-time PCR reaction tubes contained 2 µL of the cDNA, 1 µL of each of forward and reverse primers, 7.5 µL SYBR green PCR master mix, and 5.5 µL DEPC water, applying the Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagene-6000) instrument and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagene). As the housekeeping gene, the 16srDNA gene (Metabion, Germany) was used.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 software was used for statistical analyses. Due to the normality of the data, one way ANOVA test was utilized to compare means.

4. Results

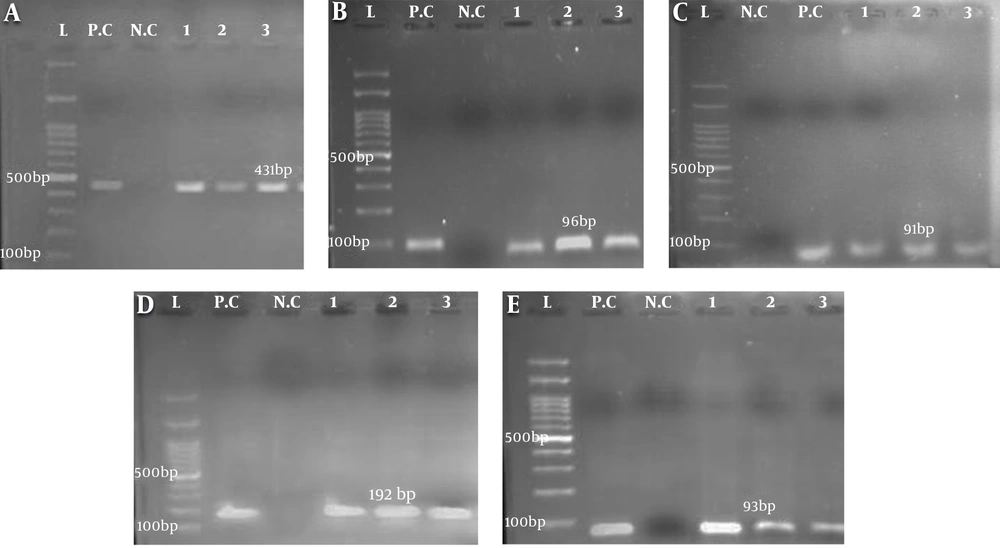

Out of 81 dental plaque samples, 32 (39.5%) were identified as S. mutans strains. Regarding the age of patients, the isolated bacteria were categorized into four different age groups with the highest number (16 cases, 50%) of S. mutans strains belonging to the age group of < 7 years. There was a significant relationship between dental caries and the presence of S. mutans (P < 0.05). Molecular analysis of the gtfD, gtfB, gtfC, spaP, and luxS genes showed that all S. mutans isolates expressed the gtfD gene. The frequency of the studied genes was as follows: gtfB17 (53.12%), gtfC19 (53.37%), spaP13 (40.62%), and luxS23 (17.87%) (Figure 1).

Gel electrophoresis of PCR amplicons of genes from isolated Streptococcus mutans, A, gtfD (431 bp); B, gtfB (96 bp); C, gtfC (91 bp); D, spaP (192 bp); E, luxS (93 bp). L, Ladder (100 bp); P.C, positive control S. mutans ATCC35866; N.C, negative control (the tube containing distilled water, gene primers, and Master Mix). The numbers indicate the samples expressing the target genes.

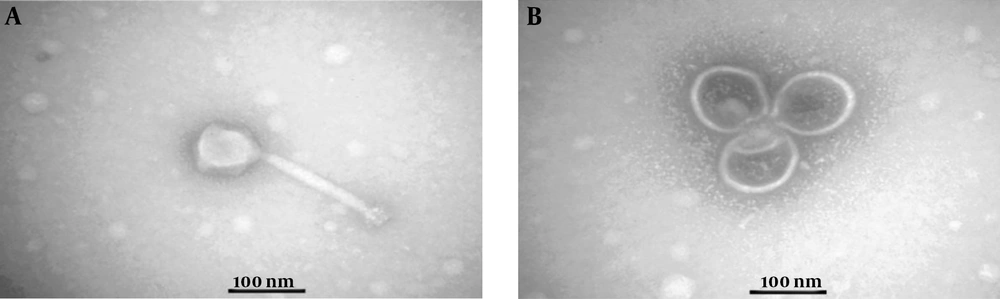

Regarding the ability of S. mutans isolates to form biofilms, it was noticed that 5 (15.6%) isolates produced no biofilms while 3 (9.4%), 21 (65.6%), and 3 (9.4%) isolates formed weak, moderate, and strong biofilms, respectively. Following the purification of phages, the lytic plaques degrading S. mutans biofilms were seen on the surface of the plate (Figure 2). Transmission electron microscopy images revealed the isolation of two lytic bacteriophages. One of them had an icosahedral head and a tail, belonging to the Siphoviridae family. The other one had a non-enveloped icosahedral head and no tail and belonged to the Tectiviridae family (Figure 3). The isolated phages showed a decrease in the number of plaques at 50°C and higher temperatures and revealed high stability at pH = 7 while they tolerated pH = 3 - 6.

Transmission electron micrographs: A, The morphology of Siphoviridae phage, showing an icosahedral head (88 nm) and a tail (181 nm); B, The morphology of Tectiviridae phage, showing an icosahedral head (108 nm) without a head-tail. The negative control was stained by uranyl acetate 2%. TEM Zeiss -EM10C-100 KV

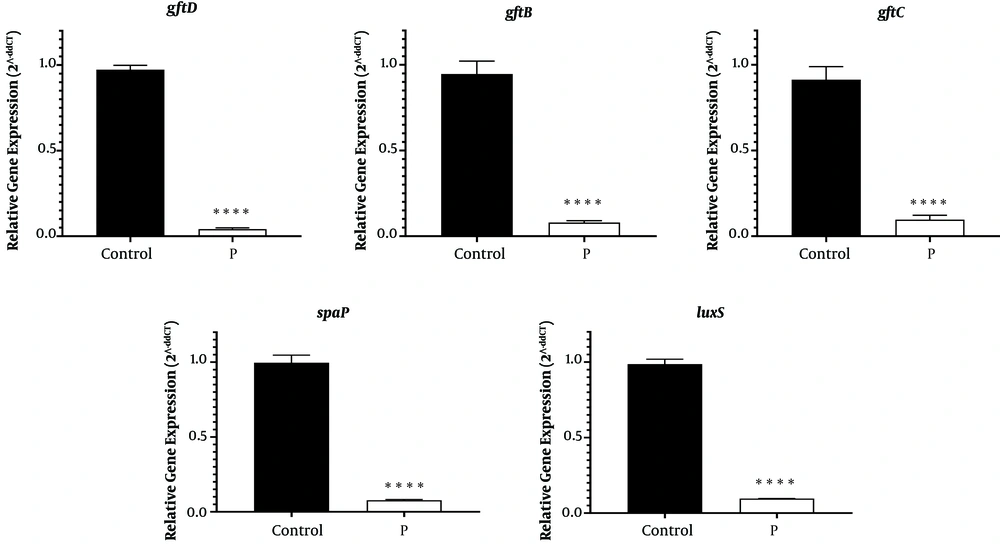

Bacteriophage host assessment showed specificity towards the isolated S. mutans strains. The addition of the isolated lytic bacteriophages of S. mutans prevented the formation of biofilm by these bacteria up to 97%. Real-time PCR findings showed that in the presence of bacteriophages, the expressions of the assessed genes significantly reduced (Figure 4, P < 0.0001).

5. Discussion

Dental caries is a damage to a tooth that can happen when decay-causing bacteria in the mouth produce acids and start to decay the tooth’s surface (17). When saliva, foods, and oral bacteria are combined together, sticky pale-yellow plaques are formed between teeth and gums. About 4 h after brushing, dental plaques, as structural and functional biofilms, begin to form. Streptococci are known as the main colonizers of oral biofilms, which account for about 63% of the bacteria isolated at the early stages of enamel biofilm formation. Streptococcus mutans is able to directly bind to receptors on salivary pellicles (18). In this study, 32 (39.5%) S. mutans isolates were identified with the highest number (16, 50%) being related to the patients under the age of seven years. The highest number of referrals was seen in 4-year-old children. There was a significant relationship between dental caries and the presence of S. mutans (P < 0.05).

Various studies have been performed in Iran and abroad to assess the relationship between S. mutans and tooth decay index, especially among preschool children. The results of Batoni et al. (19), Okada et al. (20), Soltan Dallal et al. (21), and Ghasempour et al. (22) indicated that S. mutans was the main pathogen linked with dental caries with a remarkably higher frequency than other oral streptococci, especially among children under seven years of age. Our findings and those of other studies show that the presence of S. mutans in the oral cavity exposes individuals to a high risk for dental plaque formation. Differences in the reported frequencies of S. mutans probably reflect variations in the genetics, culture, and diets of people in different regions and countries.

Phage therapy is considered a viable alternative for the treatment and control of pathogenic bacteria (23). In this study, we isolated phages from urban wastewater and tested the ability of the bacteriophages in reducing biofilm formation by S. mutans and inhibiting the expression of the genes involved in biofilm production. In earlier reports, Beheshti Maal et al. (24) and Dalmasso et al. (25) extracted S. salivarius and S. mutans phages from the waters of the Caspian Sea and saliva, respectively. However, we here isolated phages from raw urban sewage. According to TEM micrographs, two different lytic bacteriophages were identified, belonging to the Siphoviridae and Tectiviridae virus families. As mentioned, Beheshti Maal et al. (24) isolated two bacteriophages against S. salivarius from the Caspian Sea, which belonged to the Tectiviridae and Cystoviridae families. Dalmasso et al. (25) by screening 85 saliva samples, isolated only one phage against S. mutans. On the other hand, Bacharach et al. (26) and Hitch et al. (27) could not isolate any phage against S. mutans from saliva, which is probably due to the difficulty of isolating phages from the oral cavity. So, using a proper source for isolating bacteriophages is important, and according to our study, raw urban sewage can be a better source for phage isolation. The lytic bacteriophages isolated in the present study were specific for S. mutans.

In this study, all the isolates contained S. mutans specific gtfD. Besides, luxS, gtfB, and gtfC genes were identified in 23 (71.87%), 17 (53.12%), and 19 (53.37%) isolates, respectively. The least frequency was related to the SpaP gene, rendering positivity in 13 (40.62%) isolates. In another study on 61 dental plaque samples, 19 (41.7%) and 8 (4.1%) isolates expressed the gtfB and gtfC genes, respectively (28). However, the relationship between gtfS genes’ expression and the quantity of produced ECP differed among clinical S. mutans isolates. Normally, various enzymes can influence the expression and activity of the genes involved in biofilm formation by S. mutans. For the first time, we investigated the effects of bacteriophages on the expression of the genes related to biofilm production by a bacterium. Our results showed that lytic bacteriophages strongly inhibited the expression of the assessed genes. Our molecular results (gene expression) were consistent with the effects of bacteriophages on the biofilm formation ability of S. mutans, as evidenced by the microtiter plate method, which its results agreed with those of previous phenotypic reports conducted by Beheshti Maal et al. (24) and Dalmasso et al. (25). Overall, phages and their enzymes can successfully be used to target oral bacteria, in planktonic and biofilm forms, and control the formation of oral biofilms.

5.1. Conclusions

Drug resistance, especially in the biofilm mode, is one of the most challenging issues for treating bacterial infections. To overcome this problem, bacteriophages can be used as new alternatives to limit the growth of pathogenic bacteria and develop new approaches to design effective antibacterial drugs. Based on our results and those of previous studies, phage therapy can provide an efficient way to control biofilm development and help to reduce the colonization of tooth surfaces by S. mutans.