1. Introduction

Intracranial infection is a common complication after neurosurgery. The blood-brain barrier prevents many antibiotics from reaching effective therapeutic concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain tissue, making anti-infection treatment difficult. In recent years, Acinetobacter baumannii has been considered the dominant causative agent of Gram-negative meningitis, accounting for 3.6 to 11.2% of hospital bacterial meningitis cases (1). The resistance rate of A. baumannii has demonstrated a significant increase (2), and the selection of effective antibacterial drugs, especially for pediatric patients, has become a severe challenge to clinicians. In this study, we report a five-year-old child with extensively drug-resistant intracranial A. baumannii (XDRAB) infection successfully treated with colistin via the intrathecal (ITH)/intraventricular (IVT) route combined with intravenous (IV) tigecycline and cefoperazone/sulbactam.

2. Case Presentation

A five-year-old boy weighing 22 kg was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of spontaneous intraventricular hemorrhage and underwent bilateral frontal external ventricular drainage on the second day of admission. After the operation, 150 ml of pale red CSF was drained from the bilateral ventricular drainage tube. On the fifth day of admission, the boy presented with remittent fever (peak 38.6°C) associated with meningeal signs such as recurrent vomiting and turbid CSF. Blood analysis showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 16.58 × 109/L, with 87.2% neutrophils, and C-reactive protein (CRP) < 8 mg/L. Empirical antimicrobial treatment was initiated with vancomycin (60 mg/kg/d, every eight hours, intravenous drip) and cefepime (100 mg/kg/d, every 24 hours, intravenous drip) (3). On the seventh day of admission, the patient underwent cerebral digital subtraction angiography (DSA), which showed a right temporal, occipital arteriovenous malformation. On the eighth day of admission, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRI) showed residual hemorrhage in the right ventricle (Figure 1A).

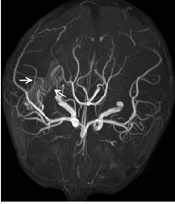

The dynamic changes of cranial contrast-enhanced MRI before and after treatment of ventriculitis. (A) On the seventh day of admission, there was still residual hemorrhage in the right ventricle (marked by the white arrow), and there was no apparent ventriculitis-related imaging manifestation; (B) On the 20th day of admission, the residual hemorrhage in the ventricle was significantly reduced. There was an imaging manifestation of ventriculitis-ependymal enhancement and increased meningeal enhancement along the cerebral sulci (marked by the white arrow); (C) After three months, ependymal enhancement and meningeal enhancement disappeared.

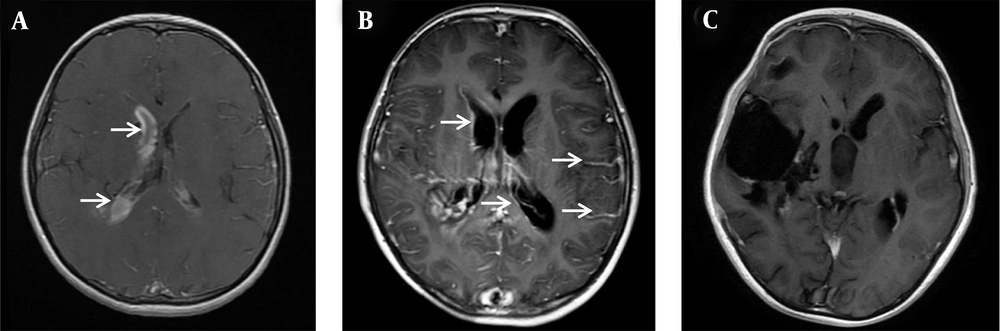

On the 10th day of admission, the patient still had a recurrent fever, headache, and vomiting. The CSF analysis revealed a WBC count of 410 × 106/L, 75% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and a glucose concentration of 3.28 mmol/L. The antimicrobial treatment was switched to meropenem (120 mg/kg/d, every eight hours, intravenous drip) combined with vancomycin (60 mg/kg/d, every six hours, intravenous drip). On the 13th day of admission, cranial Computed Tomography (CT) showed that the intraventricular hemorrhagic foci were significantly absorbed. Due to the poor management of CNS infection, the ventricular drainage was removed, and lumbar cistern drainage was inserted. On the 15th day of admission, CSF analysis showed a WBC count of 4582 × 106/L and a glucose concentration of 1.0 mmol/L. The CSF culture was positive for A. baumannii, and a drug susceptibility test showed that it was sensitive only to polymyxin (MIC = 1 μg/mL) and tigecycline (MIC ≤ 1 μg/mL). Acinetobacter baumannii was identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Dalton, Germany). Susceptibility to antibiotics was verified by an automatic drug sensitivity analysis system (Vitek 2 compact system) and an ASTGN card (bioMérieux, France) combined with the disc diffusion method and broth microdilution method, interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute criteria (4). On the 16th day of admission, the antimicrobial treatment was switched to tigecycline (1.5 mg/kg for the first dose and 1 mg/kg/time for the second dose, every 12 hours, intravenous drip) plus cefoperazone/sulbactam (240 mg/kg/d, every six hours, intravenous drip) and amikacin (10 mg/time, every 24 hours, intraventricular injection) (5). On the 21st day of admission, the patient’s body temperature was still high, with a Tmax of 39.1°C. The WBC count and glucose concentration in the CSF did not improve, and the CSF culture results and drug susceptibility were the same as those on the 15th day after admission. Besides, CE-MRI showed apparent signs of ventriculitis (Figure 1B), and Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) showed a malformed vascular mass in the right temporal lobe (Figure 2), consistent with DSA results.

On the 22nd day of admission, the tigecycline dosage was adjusted to 1.5 mg/kg q12h, and intraventricular amikacin was stopped and replaced with intraventricular polymyxin B (50,000 units/time, every 24 hours) (3). The boy had no fever on the 25th day of admission thereafter, with negative CSF cultures on the 27th day of admission onward. On the 33rd day of admission, the lumbar cistern drainage was removed, and an Ommaya reservoir was inserted into the left lateral ventricle. Subsequently, polymyxin B was administered by the Ommaya reservoir. On the 50th day of admission, the polymyxin B treatment course stopped after four weeks of implementation. The combined cefoperazone/sulbactam and tigecycline treatments continued to complete a course of six weeks. Before discharge, repeated CSF cultures were negative, and the boy’s general condition was good. At the third-month follow-up, the boy underwent the embolization of the right temporal, occipital arteriovenous malformation. Besides, MRI showed disappeared ependymal and meningeal enhancement (Figure 1C). The boy was in good clinical condition at the one-year follow-up without any abnormal tooth or bone development.

3. Discussion

Acinetobacter baumannii is a severe hospital-acquired pathogen. The risk factors of CNS infection include traumatic or surgical damage, CSF leakage, and internal ventricular catheters (ie, CSF shunts) (2). Other factors associated with the development of postneurosurgical intracranial infections include concomitant infection at the incision site and the duration of surgery for more than four hours (6). An analysis of bacterial meningitis in children revealed that A. baumannii-induced pediatric bacterial meningitis was closely associated with underlying diseases, including intracranial tumors, hydrocephalus, intracranial hemorrhage, admission to the intensive care unit, and invasive procedures such as neurosurgery (7). Studies have shown that long-term and high-dose administration of antibiotics can inhibit the growth of normal human flora and increase the colonization of drug-resistant A. baumannii, thereby increasing the chance of infection and drug resistance (8).

The pediatric patient in this study underwent bilateral frontal external ventricular drainage for severe ventricular hemorrhage, and an external drainage tube was placed after the surgery. Due to postoperative recurrent fever, postoperative antibiotics were administered short-term. We believe that the main risk factors for intracranial A. baumannii infection in this pediatric patient were his underlying disease, neurosurgery, placement of the external drainage tube, and not short-term use of antibiotics. Acinetobacter baumannii is the most commonly isolated Gram-negative bacterium in the CSF in China. The resistance rate of A. baumannii to most antibacterial drugs is more than 45%; in particular, the resistance rate to carbapenems exceeds 70%, and it has low resistance only to tigecycline and polymyxin B (9). Drug-resistant A. baumannii can be divided into multidrug-resistant A. baumannii (MDRAB), XDRAB, and Pandrug-resistant A. baumannii (PDRAB) (10). Extensively drug-resistant A. baumannii (XDRAB) is defined as A. baumannii that is insensitive to all antimicrobial species (at least one in each category), except for those in categories 1 - 2 (10). In the present pediatric case, XDRAB was cultured from the CSF and was sensitive only to colistin and tigecycline. However, among pediatric patients, many limitations in the choice of antibiotics and poor CSF penetration of available antibiotics make the treatment of intracranial infection caused by XDRAB very difficult.

As known, ITH or IVT colistin administration has been considered a safe and effective treatment for intracranial infections caused by XDRAB. De Bonis et al. reported that IV + IVT colistin treatment achieved 100% CSF sterilization (a negative CSF culture result) versus 33.3% with IV colistin alone, suggesting that IVT colistin administration is more effective than IV colistin alone (11). Karaiskos et al. investigated 81 patients (including 10 children and neonates) with A. baumannii meningitis treated with IVT and/or ITH colistin and found that 89% (72/81) of the patients achieved successful clinical and bacteriological outcomes (1). Among pediatric patients, a dose of 2,000 IU/kg (0.16 mg/kg) up to 125,000 IU (10 mg) colistin was administered via the IVT or ITH route, and 90% (9/10) of children were cured. Polymyxin B and colistin (polymyxin E) are polypeptide antibiotics and are essentially equivalent due to similarities in their chemical structure and activity spectrum.

Increasing evidence shows that IVT polymyxin B administration effectively acts against MDRAB-induced intracranial infections (12). Polymyxin B is also recommended for antimicrobial therapy in patients with A. baumannii-induced ventriculitis and meningitis. Neurotoxicity is a common adverse reaction to IVT/ITH injection of polymyxins, with an incidence of up to 21.7%, primarily including chemical ventriculitis, chemical meningitis, and epilepsy (1). In the present pediatric case, CSF sterilization was detected four days after ITH administration of polymyxin B dosage of 5 mg every 24 hours. The child received ITH/IVT polymyxin B for four weeks in total and did not show any related adverse reactions, such as chemical ventriculitis, chemical meningitis, or epilepsy, during the hospital stay. Furthermore, no related adverse reactions were observed one year after discharge.

Tigecycline and sulbactam are alternative potential antimicrobial agents against carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii. Tigecycline has poor permeability to the blood-brain barrier. Ray et al. reported that low CSF tigecycline concentrations failed treatment in a patient with A. baumannii cerebritis (13). Clinical case reports have shown that intravenous overdose administration of tigecycline can effectively treat XDRAB-induced intracranial infection (14). Falagas et al. also reported that an overdose of tigecycline has certain advantages over conventional doses (15). The ITH or IVT administration of tigecycline can increase the concentration of tigecycline in the CSF to successfully treat XDRAB and even colistin-resistant Acinetobacter strains (16). Sulbactam offers direct antimicrobial activity against Acinetobacter species, including XDRAB and PDRAB (17). Cefoperazone and sulbactam can penetrate the CSF in bacterial meningitis, and the CSF penetration of cefoperazone/sulbactam may enhance after neurosurgical impairment of the blood-brain barrier (18). Tigecycline combined with cefoperazone/sulbactam is more effective than cefoperazone/sulbactam alone against pulmonary MDRAB and XDRAB infections (19). Besides, high-dose cefoperazone/sulbactam sodium improves the antibacterial activity of tigecycline against XDRAB (20). In addition to ITH polymyxin B administration, the child, in this case, received IV tigecycline plus cefoperazone sulbactam at the maximum dose for another two weeks after ITH polymyxin B administration until the patient’s clinical conditions were stable.

The application of tigecycline may increase the all-cause mortality of patients; however, pediatric clinical trials on the efficacy and safety of tigecycline have not been conducted. Additionally, because tigecycline affects bone and tooth development in children that are similar to those of tetracycline antibiotics, the instructions clearly state that tigecycline is prohibited for children under eight years of age. Recently, many reports on the efficacy and safety of tigecycline in children have been published. Lin et al. reported that among 47 cases of MDRAB infection treated with tigecycline, the overall clinical improvement rate was 47.3%, the pathogen clearance rate was 38.9%, and no severe side effects were observed (21). A systematic evaluation of tigecycline in children under eight years showed that tigecycline had an effectiveness rate of 74.2% and was well tolerated (22). The boy in the present study received intravenous tigecycline administration for six weeks in total. One year after discharge, he had no abnormal tooth or bone development.

3.1. Conclusions

Intracranial XDRAB infection is associated with high morbidity and mortality in children. Besides, ITH/IVT polymyxin B combined with IV tigecycline and cefoperazone sulbactam could be an effective therapy in the treatment of intracranial XDRAB infection. In this case, we did not observed any related adverse reactions relted tegacyclin and ITH/IVT polymyxin B. However, multicenter randomized studies are still needed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of tigecycline and ITH/IVT polymyxin B in pediatric patients.