1. Background

Brucellosis is a zoonotic bacterial infection caused by Brucella species and continues to be a major public health issue, especially in developing countries (1, 2). Approximately half of a million new human brucellosis infections are reported annually, and it is still endemic, mainly in the Mediterranean basin, Middle East, Latin America, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent (1, 3). The disease is usually transmitted by close contact with infected animals (most commonly sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs) or by consuming unpasteurized milk and milk products (2-4). Human brucellosis is a systemic inflammatory disease that can affect any organ or system of the body. Patients with brucellosis may present diverse non-specific clinical manifestations, such as fever, fatigue, sweating, arthralgia, myalgia, headache, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. The definitive diagnosis frequently depends on the results of laboratory testing because there are no disease-specific pathognomonic symptoms or signs (1, 5-7).

Several bacteriological, serological, and molecular methods have been improved for the laboratory diagnosis of brucellosis. Each of these methods has advantages and limitations and needs careful interpretation. Although bacterial culture is accepted as the superior diagnostic method, the isolation rate of Brucella spp. varies based on the disease stage, previous antibiotic use, clinical sample, and the culture technique, and culture is generally unsuccessful owing to the inability to provide optimum culture conditions (1, 6, 8). Therefore, serological tests are more widely used as diagnostic and screening tools in routine laboratory practice. However, serological tests sometimes yield false positive or negative results due to cross-reactions with other Gram-negative bacteria, the presence of blocking antibodies, or high antibody titers interfering with the antigen-antibody complex formation known as the prozone phenomenon (4, 8-10). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been demonstrated to be more sensitive and specific than culture and serological methods in the laboratory diagnosis of brucellosis (1, 6). Nevertheless, due to the high costs, and long and labor-intensive process, PCR assays are not appropriate for widespread use in many medical laboratories, particularly in developing countries.

Because of the difficulties in the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of brucellosis, identifying novel, specific, and cost-effective biomarkers is important for resolving the diagnostic obstacles, especially in endemic regions. The systemic inflammatory burden could be evaluated using various biomarkers. Increased values of C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), two well-known acute phase reactants, have been usually reported in patients as a result of inflammatory response in brucellosis (7, 8, 11-14). The CRP to albumin ratio (CAR), obtained by dividing CRP by albumin, is a new biomarker extensively studied as a diagnostic and prognostic tool in various diseases (15-18). In recent years, hematological and biochemical parameters, such as neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio (MHR), have been investigated as potential indicators of systemic inflammation in several infectious and non-infectious diseases (7, 11, 19-23). These inflammatory markers are broadly available and affordable parameters that can be easily calculated based on routine complete blood count (CBC) and biochemical analysis.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the predictive performance of novel and traditional inflammation markers to diagnose brucellosis and guide clinicians in the diagnostic process.

3. Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted at Suleyman Demirel University Research and Practice Hospital, Isparta, Turkey. The medical records of patients with brucellosis and healthy controls who were admitted to the inpatient/outpatient clinics of the hospital during July 2018 - January 2020 were analyzed.

3.1. Patients and Controls

Fifty-five patients with newly diagnosed brucellosis and 60 healthy controls with similar age and gender distribution were enrolled in the study. Participants with any autoimmune disease, malignancy, severe chronic disease, and recent infectious disease were excluded from the study. In the patient group, the diagnosis of brucellosis was based on bacteriological, serological, and clinical data according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reference guidelines and previous reports (6-8, 11-14, 20, 21, 24). Confirmed brucellosis was defined as the positivity of blood culture for Brucella spp. and/or serological test positivity (a four-fold or greater rise in antibody titer between two serum specimens obtained at least two weeks apart) by both serological methods in the presence of compatible clinical symptoms, signs, and anamnesis. Presumptive brucellosis was defined as serological test positivity (a single antibody titer ≥ 1/320) in the presence of clinical symptoms, signs, and anamnesis. All participants in the patient group met the criteria for confirmed brucellosis and received specific antimicrobial therapy (a combination of doxycycline and rifampin or streptomycin for 6 weeks). The control group consisted of healthy volunteers attending outpatient clinics for a routine health check-ups. None of the control subjects met the criteria for confirmed or presumptive brucellosis.

3.2. Laboratory Analysis

Venous blood samples (5 - 8 mL) were obtained from each participant and were centrifuged before analysis. The specific antibodies against Brucella infection were detected by the Brucellacapt test (Vircell, Granada, Spain) and Brucella Coombs gel test (Across Gel, Dia Pro, Turkey). The serum samples were analyzed at the dilutions of 1/20 - 1/5120. The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibody titers at 1/320 and higher for both serological methods were interpreted as a positive reaction for brucellosis, while those lower than 1/320 were interpreted as negative.

Blood cultures were processed using the BacT/ALERT 3D (bioMérieux, France) automated blood culture system. The isolated bacterial strains were identified by conventional methods (colony morphology, Gram staining, biochemical tests, oxidase, and urease tests). Serum biochemical parameters were analyzed using Beckman Coulter AU5800 clinical chemistry analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA). The CBC and ESR measurements were performed using Beckman Coulter UniCel DxH 800 hematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA) and Test-1 analyzer (Alifax, Padova, Italy), respectively. For CBC and ESR analyzes, blood specimens withdrawn from each participant were collected in blood tubes containing citrate or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. All assays were performed according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. The values of CAR, NLR, LMR, PLR, and MHR were calculated based on CBC and biochemical analysis.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The SPSS software version 22 was used for statistical analysis (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The continuous variables were compared between the groups utilizing the Mann-Whitney U test or Student's t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Results of descriptive statistics were presented as frequency and percentage, or mean ± standard deviation. Moreover, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted for significant variables, and the areas under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC) values with 95% CI were calculated. The optimal cut-off values were identified for predicting brucellosis. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated. The correlations between variables were assessed by Spearman’s correlation analysis. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

The comparison of demographic features, including age and gender, and the results of biochemical tests, CBC, and ESR between the patient and control groups is demonstrated in Table 1. The patients with brucellosis had significantly higher hsCRP, CAR, ESR, monocyte, MHR, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and creatinine levels compared to the controls. On the other hand, patients had significantly lower mean platelet volume (MPV), LMR, albumin, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels than the control group (P < 0.05). No significant difference was found in leukocyte count, neutrophil, lymphocyte, hemoglobin, red blood cell distribution width (RDW), platelet, NLR, PLR, fasting blood glucose, alanine aminotransaminase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels between the two groups (P > 0.05).

| Patient Group (N = 55) | Control Group (N = 60) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 45.73 ± 14.85 | 49.78 ± 12.8 | 0.119 |

| Gender | 0.626 | ||

| Male | 30 (54.5) | 30 (50) | |

| Female | 25 (45.5) | 30 (50) | |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 21.92 ± 20.25 | 2.38 ± 1.71 | < 0.001 |

| CAR | 6.06 ± 6.16 | 0.57 ± 0.41 | < 0.001 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 28.4 ± 21.51 | 9.51 ± 6.92 | < 0.001 |

| Leukocyte (×103/µL) | 7.44 ± 2.55 | 6.83 ± 2.04 | 0.159 |

| Neutrophil (×103/µL) | 4.68 ± 2.31 | 4.15 ± 1.57 | 0.146 |

| Lymphocyte (×103/µL) | 1.96 ± 0.58 | 1.97 ± 0.57 | 0.89 |

| Monocyte (×103/µL) | 0.62 ± 0.24 | 0.52 ± 0.2 | 0.015 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.66 ± 1.43 | 14.05 ± 1.78 | 0.201 |

| RDW (%) | 14.65 ± 1.58 | 14.56 ± 1.86 | 0.779 |

| Platelet (×103/µL) | 258.94 ± 93.34 | 255.43 ± 58.99 | 0.808 |

| MPV (fL) | 8.12 ± 0.92 | 8.53 ± 0.75 | 0.015 |

| NLR | 2.61 ± 1.52 | 2.21 ± 0.98 | 0.094 |

| LMR | 3.61 ± 1.89 | 4.17 ± 1.44 | 0.01 |

| PLR | 142.23 ± 66.04 | 137.64 ± 45.04 | 0.662 |

| MHR | 17.79 ± 7.55 | 11.82 ± 5.08 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 101.68 ± 14.64 | 102.71 ± 32.3 | 0.829 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 26.7 ± 19.23 | 22.04 ± 10.02 | 0.103 |

| AST (IU/L) | 27.69 ± 13.37 | 22.42 ± 6.87 | 0.008 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 14.14 ± 4.16 | 14.21 ± 3.44 | 0.92 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.79 ± 0.17 | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 0.045 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3.85 ± 0.5 | 4.16 ± 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 133.97 ± 61.34 | 131.6 ± 55.3 | 0.828 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 170.2 ± 43.26 | 182.89 ± 37.16 | 0.031 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 106.53 ± 34.17 | 110.58 ± 31.01 | 0.507 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 36.9 ± 9.31 | 45.97 ± 9.75 | < 0.001 |

Comparison of Demographic Features and Laboratory Findings Between the Patient and Control Groups

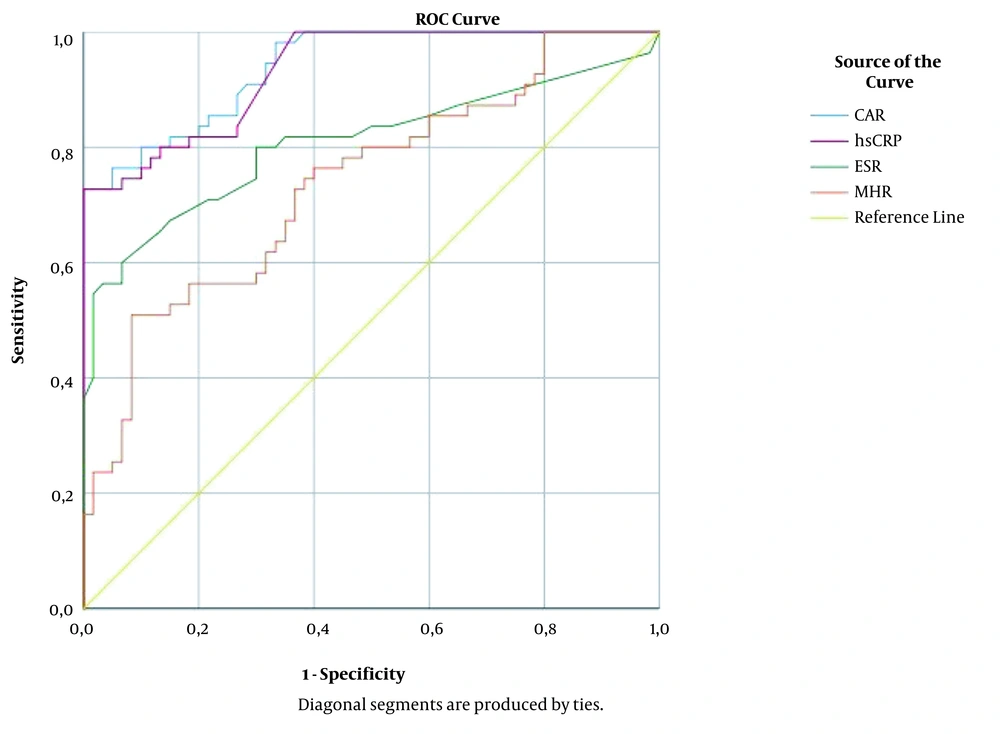

The correlations between inflammation-associated laboratory parameters in patients with brucellosis are shown in Table 2. The CAR levels were positively correlated with hsCRP, ESR, and MHR, while negatively correlated with LMR, MPV, and albumin. The MHR levels had a positive correlation with CAR, hsCRP, ESR, and NLR and negative correlations with LMR, MPV, and albumin. The ROC curve analysis for the significant variables was performed to evaluate their predictive performance for diagnosing brucellosis. The AUC values for CAR, hsCRP, ESR, and MHR were calculated as 0.939 (95% CI: 0.901 - 0.978), 0.932 (95% CI: 0.891 - 0.974), 0.807 (95% CI: 0.721 - 0.892), and 0.737 (95% CI: 0.647 - 0.828), respectively (Figure 1). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV values are presented in Table 3 at the optimal cut-off values of 0.8 and 1.5 for CAR and the optimal cut-off values of 11 and 18.1 for MHR.

| Parameter | CAR | hsCRP | ESR | MHR | LMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR | - | 0.996 (< 0.001) | 0.596 (< 0.001) | 0.476 (< 0.001) | -0.267 (0.004) |

| hsCRP | 0.996 (< 0.001) | - | 0.589 (< 0.001) | 0.472 (< 0.001) | -0.260 (0.005) |

| ESR | 0.596 (< 0.001) | 0.589 (< 0.001) | - | 0.187 (0.045) | -0.180 (0.054) |

| MHR | 0.476 (< 0.001) | 0.472 (< 0.001) | 0.187 (0.045) | - | -0.653 (< 0.001) |

| LMR | -0.267 (0.004) | -0.260 (0.005) | -0.180 (0.054) | -0.653 (< 0.001) | - |

| MPV | -0.342 (< 0.001) | -0.342 (< 0.001) | -0.231 (0.013) | -0.340 (< 0.001) | -0.211 (0.024) |

| Albumin | -0.410 (< 0.001) | -0.350 (< 0.001) | -0.284 (0.002) | -0.255 (0.006) | 0.193 (0.038) |

| NLR | 0.043 (0.648) | 0.048 (0.608) | 0.126 (0.178) | 0.246 (0.008) | -0.665 (< 0.001) |

| PLR | -0.015 (0.871) | -0.029 (0.757) | 0.197 (0.035) | -0.065 (0.491) | -0.414 (< 0.001) |

| RDW | 0.103 (0.273) | 0.089 (0.345) | 0.206 (0.027) | 0.060 (0.526) | -0.024 (0.801) |

Correlation Between Inflammation-Associated Laboratory Parameters [r Value (P-Value)]

| Cut-off Value | Sensitivity % | Specificity % | PPV % | NPV % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR ≥ 0.8 | 90.9 (80.4 - 96.1) | 71.7 (59.2 - 81.5) | 74.6 (63.1 - 83.5) | 89.6 (77.8 - 95.5) |

| CAR ≥ 1.5 | 72.7 (59.8 - 82.7) | 98.3 (91.1 - 99.7) | 97.6 (87.4 - 99.6) | 79.7 (69.2 - 87.3) |

| MHR ≥ 11 | 80 (67.6 - 88.4) | 51.7 (39.3 - 63.8) | 60.3 (48.8 - 70.7) | 73.8 (58.9 - 84.7) |

| MHR ≥ 18.1 | 50.9 (38.1 - 63.6) | 91.7 (81.9 - 96.4) | 84.8 (69.1 - 93.3) | 67.1 (56.3 - 76.3) |

Diagnostic Performance of CAR and MHR Cut-off Values in Predicting Brucellosis According to ROC Curve Analysis

5. Discussion

The clinical and laboratory diagnosis of brucellosis continues to be a challenge for clinicians because of its non-specific clinical manifestations, low isolation rates in blood cultures, and the possibility of false-positive or false-negative results in the serological methods. Nevertheless, an early and accurate diagnosis is essential to prevent the mismanagements and serious complications associated with brucellosis. Although numerous investigations have attempted to identify the predictive biomarkers for the diagnosis of brucellosis, there are yet no clinically valuable biomarkers that could be specific for brucellosis (7, 8, 11-14, 19-21). In the current study, besides well-recognized inflammatory markers, such as hsCRP and ESR, we investigated novel inflammatory markers which can reflect systemic inflammatory burden in patients with brucellosis.

It is known that positive acute phase reactants, CRP and ESR, are increased in brucellosis as a consequence of the inflammatory process. CRP is a sensitive but non-specific biomarker of systemic inflammation and is synthesized by the liver in response to proinflammatory cytokine signaling primarily mediated by neutrophils and monocytes (12, 13, 25). Serum CRP levels elevate within hours of inflammation and infection and can be easily determined by the high-sensitivity assays in routine laboratory practice. The hsCRP measurements detect even low serum concentrations of CRP, which are significantly associated with certain inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases. Many studies have reported the clinical utility of CRP and ESR in brucellosis (7, 8, 11-14, 26).

In a prospective case-control study in Iran, Akya et al. reported significantly higher CRP levels in patients with brucellosis compared to healthy individuals. The authors observed higher ESR values in patients with brucellosis than in healthy subjects. However, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (8). In another study, Celik et al. revealed statistically significant increases in CRP and ESR in patients with brucellosis compared to the control group (12). A multicentric study carried out in Turkey demonstrated mild to moderate elevations in CRP and ESR in patients with genitourinary brucellosis (26). Similarly, in the present study, hsCRP and ESR values were significantly higher in patients than in control subjects (Table 1), and a positive correlation (r = 0.589, P ≤ 0.001) was found between hsCRP and ESR (Table 2). The findings of the current study and previous reports suggest that serum CRP level and ESR could be used as suitable markers of systemic inflammation in brucellosis.

Albumin is a negative acute-phase reactant produced in the liver, and its level in the serum decreases during inflammation. The combination of CRP and albumin into a single index (ie, CAR) has been proposed previously as a strong biomarker of systemic inflammation. CAR has been widely investigated in recent years as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in many clinical conditions, such as sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis, and some malignancies (15-18). Yılmaz suggested that CAR can be used as a promising potential inflammatory marker for determining the prognosis in acute pancreatitis cases (16).

In another study, Kim et al. reported that CAR was superior to CRP in predicting long-term mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock (18). However, to our knowledge, CAR has not yet been evaluated in patients with brucellosis. In the present study, it was found that patients with brucellosis had significantly higher CAR values compared to the control group (Table 1). Furthermore, positive correlations were noted between CAR, hsCRP, ESR, and MHR (Table 2), and it was observed that CAR had higher AUC values than hsCRP, ESR, and MHR (Figure 1). The cut-off values of ≥ 0.8 and ≥ 1.5 for CAR were shown to have diagnostic sensitivities of 90.9% and 72.7% and diagnostic specificities of 71.7% and 98.3%, respectively, in predicting brucellosis (Table 3).

The systemic inflammatory reaction leads to alterations in the blood levels and functions of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets. Neutrophils are among the first cells to react in the acute inflammatory response, and especially in bacterial infections, neutrophilia and relative lymphocytopenia are observed (7, 21, 27, 28). Platelets, in addition to their hemostatic functions, stimulate the release of proinflammatory cytokines and empower the migration of inflammatory cells, particularly monocytes and neutrophils, to the inflammatory sites (8, 20). Therefore, NLR, LMR, and PLR, which include neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, and platelet counts, have been regarded as the indicators that effectively reflect systemic inflammatory status. This study found higher NLR and PLR and lower LMR values in patients with brucellosis than in healthy controls. However, only the difference in LMR values between the two groups was statistically significant (Table 1).

limited number of studies have investigated NLR, LMR, and PLR values in brucellosis, and discrepant results have been reported about the significance of these values (7, 8, 11, 14, 19-21). Although no statistically significant difference was determined in terms of NLR and PLR values in our study, Aktar et al. observed significantly increased NLR and PLR in children with Brucella arthritis (20). Bozdemir et al. reported significantly increased NLR and decreased MPV in childhood brucellosis. However, the authors found no significant difference in PLR values (7). In another study, reduced LMR and MPV values and increased NLR and PLR values were found to be significantly related to specific organ involvement in adult patients with brucellosis (21). Interestingly, in contrast to the literature, Olt et al. observed significantly lower NLR values in adult patients with brucellosis compared to the controls (19). As a result, the findings related to the hematological inflammatory parameters in patients with brucellosis were relatively different in various studies and raise questions regarding the role of these markers in the diagnosis of brucellosis. These inconsistent results may be due to the differences in sample size, age groups, or study population. In the light of these data, the results for the hematological inflammatory parameters show a diverse distribution in cases with brucellosis, and more detailed and comprehensive studies are required to elucidate the role of hematological inflammatory markers in brucellosis.

It has been recently demonstrated that increased MHR levels were related to the systemic inflammatory burden, and MHR might be used as a predictive factor of future cardiovascular disease (22, 23, 29-32). Circulating monocytes and macrophages in tissues play an essential role in initiating inflammation and activating the immune response and phagocytosis. However, the recruitment of monocytes aggravates oxidative stress and inflammation, particularly in the progression of atherosclerosis. The HDL, which has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, suppresses monocyte activities and decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease by inhibiting new atherosclerotic plaque formations. As a result, combining the measurements of monocyte and HDL levels as MHR may reliably reflect the inflammatory process (22, 23, 29-32).

In an observational prospective cohort study conducted by Kanbay et al., it was noted that MHR could predict adverse clinical cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease (29). In another study, MHR was demonstrated to be an independent predictor of the severity of coronary artery disease and future cardiovascular events in patients with the acute coronary syndrome (30). There is no published report on the association between brucellosis and MHR. The present study indicated that MHR levels in patients with brucellosis were higher than those of the control subjects (Table 1). MHR values were positively correlated with CAR, hsCRP, ESR, and NLR and negatively correlated with LMR, MPV, and albumin (Table 2). The cut-off values of ≥ 11 and ≥ 18.1 for MHR were shown to have diagnostic sensitivities of 80% and 50.9% and diagnostic specificities of 51.7% and 91.7%, respectively, in predicting brucellosis (Table 3). As a practical and cost-effective marker, MHR could be used in clinical practice to assess the inflammatory status of brucellosis. Furthermore, MHR, together with hsCRP, which predicts cardiovascular risk, may provide a perspective for determining the patients with brucellosis at an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease.

The present research had some limitations that should be taken into account. First, it was a retrospective, single-center study with a relatively limited number of patients and controls. Second, we measured the levels of inflammatory markers only on admission, and we could not assess the changes in the levels of markers after the treatment. In spite of these limitations, we believe that our preliminary data can provide valuable insights for future research.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that increased CAR and MHR might reflect the systemic inflammatory burden in patients with brucellosis. These markers are significantly correlated with hsCRP and ESR and can be used as the markers of inflammation in diagnosing brucellosis. However, further studies with a larger sample size are required to support our findings and suggestions.