1. Background

Streptococcus pyogenes is a notoriously pathogenic bacterium causing a wide spectrum of diseases ranging from mild pharyngitis to severe life-threatening conditions such as streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and septicemia. Group A streptococci (GAS) disease and its sequelae such as acute rheumatic fever (ARF), rheumatic heart disease (RHD), and acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN) have contributed to significant morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). Globally, 663,000 new cases and 163,000 deaths are reported each year due to invasive GAS diseases (1). Moreover, the global emergence of macrolide-resistance strains possesses a major concern for patients with β-lactam allergy (2).

The current macrolide resistance problem is mediated by horizontal transfer of macrolide resistance genes such as ermA, ermB, and mefA as well as the spread of resistant GAS clones (3). The ermA and ermB genes, which encode proteins for ribosomal methylation as well as mefA gene, which encodes protein for macrolide efflux mechanism, are responsible for antibiotic resistance in GAS (4). Macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes isolates are documented from various studies in some Asian countries and these resistant strains can be transmitted among neighboring countries (5, 6).

The M protein is encoded by emm in the 5’ end of the hypervariable region. For the past centuries, typing of M protein was performed using specific M-typing antisera (7). Nonetheless, the reagents that were not widely available and difficulties in performing the test became the major drawbacks for its usage. In addition, there are reports of GAS strains that could not be typed by the specific antisera; thus, making it difficult to determine the distribution of M-types (7, 8). The emm typing is the analysis of the sequence of the hypervariable portion of emm gene, which is used as an alternative of M-typing using antisera. It is now considered as the gold standard since it can characterize the virulence associated M protein, which is an important epidemiological marker of S. pyogenes infections (9). Interestingly, certain emm types are associated with invasive diseases as well as antibiotic resistance (10).

Apart from emm typing, better characterization of the GAS genetic lineages are proposed by the use of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (11). MLST is a typing method that utilizes nucleotide sequence determination and targets seven neutral house-keeping genes of bacteria. The method is used to determine the relationship amongst bacteria of the same species (4). It was found very useful in the characterization and monitoring of antibiotic resistance and bacterial pathogenicity as well as the purpose of epidemiological studies since the data can be compared across the globe (12). To the authors’ knowledge, data on the erythromycin susceptibility pattern, emm type and sequence type of GAS, is still lacking among local strains in Malaysia.

2. Objectives

The current study aimed at determining the prevalence of erythromycin resistance using disk diffusion and E-test methods, detecting erythromycin resistance genes (ermA, ermB and mefA) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and characterizing the genetic profiles of GAS by emm and MLST typing methods.

3. Methods

3.1. Ethics Statement

The protocol of the study was approved by the institutional ethical committee (UPM/TNCPI/RMC/JKEUPM/1.4.18.1/F1).

3.2. Sampling and Identification

A total of 35 non-repetitive S. pyogenes species were isolated from patients in two Malaysian hospitals from August 2013 to September 2014. Clinical samples were collected from skin pus (n = 18) and blood (n = 8), followed by tissue (n = 6) and throat swabs (n = 2) (obtained from patients with gangrene and tonsillitis, respectively), and non-healing diabetic wound swab (n = 1). Invasive and non-invasive GAS isolates were categorized based on the source of isolation (13). Streptococcus pyogenes was identified by PYR test (Oxoid, United Kingdom), bacitracin susceptibility (Oxoid, United Kingdom), latex agglutination (Oxoid, United Kingdom), and 16SrRNA sequencing.

3.3. Antibacterial Susceptibility Testing

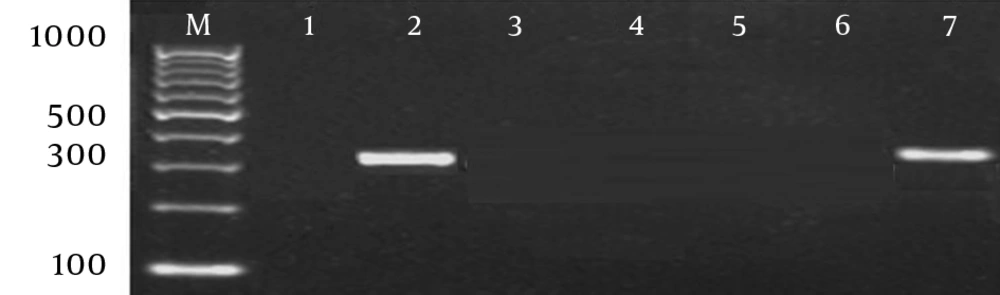

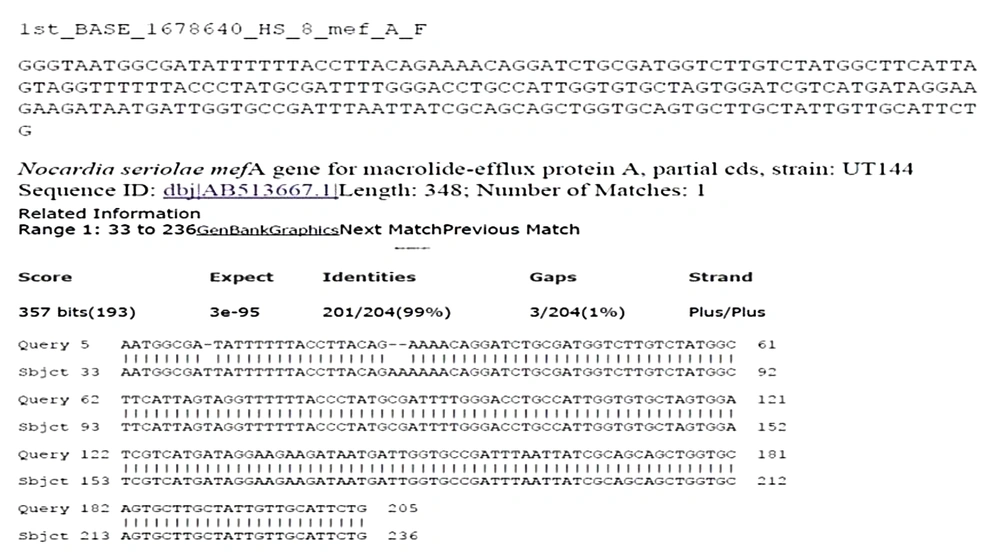

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was done by disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco, United States) supplemented with 5% sheep blood and incubated in 5% CO2 for 24 hours at 37°C according to CLSI guideline (14). The tested antibiotics were as follows: penicillin G (10 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), chloramphenicol (30 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), and vancomycin (30 µg) (Oxoid, United Kingdom). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of erythromycin was determined by E-test and interpreted based on CLSI guidelines (14). While establishing the PCR protocols, one erythromycin-susceptible isolate consistently demonstrated the presence of mefA gene in triplicate. Thus, detection of erythromycin resistance genes (ermA, ermB and mefA) was conducted in all the isolates, according to the protocol previously described (15). GOTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, USA) and Biometra thermocycler (Biorad®, Germany) were used for PCR amplification. PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis in a 2% (w/v) agarose gel (Invitrogen, USA). Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 was used as a negative control, while Staphylococcus aureus BAA ATCC 977, S. pneumoniae ATCC 700677, and S. pneumoniae ATCC 700676 were used as positive controls for ermA, ermB, and mefA, respectively.

3.4. Sequencing of emm Gene

Sequencing of the 5’ region of the emm gene was done in accordance with the protocol provided by the centre for disease control and prevention (CDC). Lysates of all the isolates were prepared and amplification was carried out by PCR using Biometra thermocycler (BioRad®, Germany). Purification and sequencing were performed by first base laboratories (1st Base laboratory Sdn Bhd, Malaysia). Sequences were edited using Bioedit software version 7.0 and compared with reference sequences using the BLAST algorithm. The emm pattern was referred to the established data based on the different types of emm obtained in the current study (16). Twenty-one representative isolates were chosen for MLST, based on the predominant emm types with the exclusion of similar isolation sites. Amplification of seven housekeeping genes and sequencing were determined as previously described (17). The MLST sequences and clonal relatedness represented as clonal clusters using eBURST clustering method were queried into the database at http://spyogenes.mlst.net. Isolates with the same emm type and sequence type (ST) were considered as the same clone.

4. Results

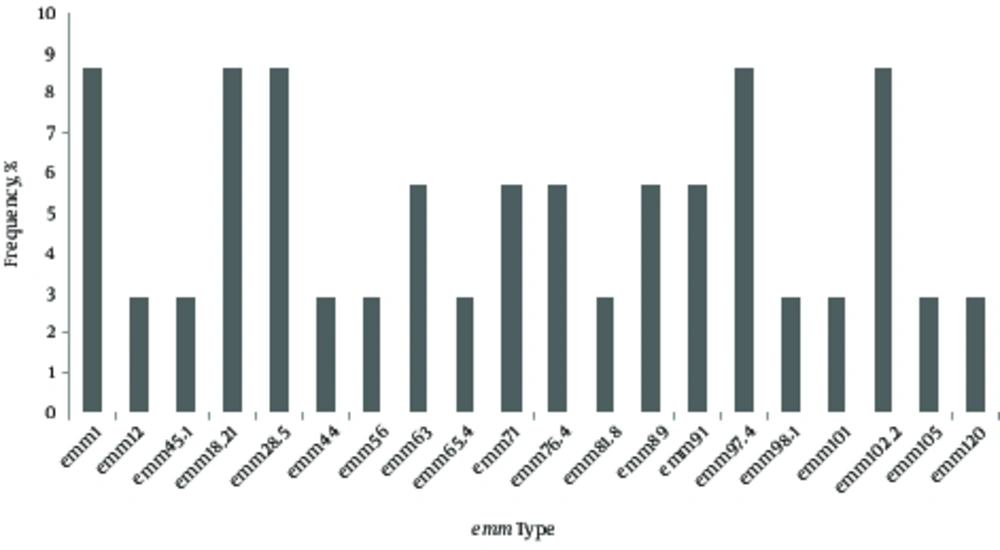

All isolates (100%) were susceptible to erythromycin, penicillin, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, and vancomycin (Table 1). However, 54.3% of GAS was resistant to tetracycline. Among the three types of resistance genes, only mefA gene was detected in one erythromycin-susceptible isolate (Figure 1). The sequence showed 99% identity to the GenBank sequence with the accession number of dbj|AB513667.1 (Figure 2). Twenty different emm types were identified, and emm1, emm18.21, emm28.5, emm97.4, and emm102.2 types/subtypes were the most frequently detected ones (8.6% for each), followed by 5.7% of emm63, emm71, emm76.4, emm89, and emm91 (Figure 3). No new emm types were identified. The emm pattern E (45.7%) was predominantly detected in the current study (Table 1). MLST analysis demonstrated eight predominant clonal clusters (CCs) and six singletons with diverse sequence types (STs) (Table 2). The predominant STs and CCs among the representative isolates were identified as follows: ST28/emm1 (CC1, 14.3%), ST60/emm102 (CC58, 9.5%) and ST473/emm28 (CC76, 9.5%), while each of these singletons (ST318/emm71 and ST402/emm18) was represented by 9.5% of the isolates (Table 2).

| Source | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Pattern | emm Pattern, nb | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | Ec | DA | TE | VA | Cl | ||||||||

| S | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | ||

| Pus | 51.4 | 0 | 51.4 | 0 | 51.4 | 0 | 25.7 | 25.7 | 51.4 | 0 | 51.4 | 0 | A - C (1), D (9), E (8) |

| Blood | 22.9 | 0 | 22.9 | 0 | 22.9 | 0 | 5.7 | 17.1 | 22.9 | 0 | 22.9 | 0 | A - C (3), D (3), E (2) |

| Tissue | 17.1 | 0 | 17.1 | 0 | 17.1 | 0 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 17.1 | 0 | 17.1 | 0 | A - C (2), E (4) |

| Wound | 5.7 | 0 | 5.7 | 0 | 5.7 | 0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 5.7 | 0 | 5.7 | 0 | A-C (1), E (1) |

| Throat | 2.9 | 0 | 2.9 | 0 | 2.9 | 0 | 2.9 | 0 | 2.9 | 0 | 2.9 | 0 | E (1) |

| Total | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 45.7 | 54.3 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | |

Abbreviations: C, chloramphenicol (30 µg); DA, clindamycin (2 µg); E, erythromycin (15 µg); n: frequency; P, penicillin G (10 µg); R, resistance; S, sensitive; TE, tetracycline (30 µg); VA, vancomycin (30 µg).

aValues are expressed as %.

bDescribed as pattern A - C: throat specialist; pattern D: skin specialist; pattern E: a generalist.

cConfirmed by E-test with MIC (susceptible < 0.25 µg/mL, intermediate 0.5 µg/mL, resistant > 1 µg/mL).

| No of Isolate | gki | gtr | murl | mutS | recP | xpt | yiqL | ST | CC | emm Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 28 | CC1 | 1 |

| HS 2 | 13 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 60 | CC58 | 102 |

| HS 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 52 | 31 | 2 | 300 | Singleton | 97 |

| HS 5 | 42 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 599 | CC83 | 76 |

| HS 6 | 4 | 3 | 62 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 313 | Singleton | 97 |

| HS 9 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 17 | 3 | 1 | 25 | CC32 | 76 |

| HS 10 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 28 | CC1 | 1 |

| HKL 2 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 3 | 101 | CC2 | 89 |

| HKL 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | CC26 | 91 |

| HKL 5 | 38 | 24 | 2 | 37 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 426 | Singleton | 63 |

| HKL 6 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 82 | 13 | 3 | 408 | CC2 | 89 |

| HKL 7 | 4 | 36 | 8 | 7 | 51 | 3 | 76 | 473 | CC76 | 28 |

| HKL 9 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 28 | CC1 | 1 |

| HKL11 | 69 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 402 | Singleton | 18 |

| HKL12 | 69 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 402 | Singleton | 18 |

| HKL14 | 2 | 10 | 35 | 7 | 2 | 57 | 1 | 318 | Singleton | 71 |

| HKL17 | 13 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 60 | CC58 | 102 |

| HKL18 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 22 | 3 | 2 | 13 | CC78 | 91 |

| HKL19 | 4 | 36 | 8 | 7 | 51 | 3 | 76 | 473 | CC76 | 28 |

| HKL22 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 50 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 306 | Singleton | 63 |

| HKL23 | 2 | 10 | 35 | 7 | 2 | 57 | 1 | 318 | Singleton | 71 |

Abbreviations: CC, clonal cluster; Gki, glucose kinase gene; gtr, glucose transporter protein gene; HKL, hospital Kuala Lumpur; HS, Hospital Serdang; murl, glutamate racemase gene; mutS, DNA mismatch repair protein gene; recP, transketolase gene; ST, sequence type; xpt, xanthine phosphoribosyl transferase gene; yiqL, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase gene.

5. Discussion

Macrolide-resistant GAS raised a considerable concern among the clinician and scientist since macrolides are commonly used as a second-line alternative for treatment (2). In addition, various reports documented the emergence of macrolide-resistant GAS in some Asian countries recently (6, 18). Ironically, all isolates (100%) were susceptible to erythromycin in the current study. High susceptibility rate (92.2%) was also observed among GAS isolates in Japan (19). More recently, an increasing trend of susceptibility towards erythromycin was reported from several countries such as Taiwan and Portugal (5, 20). These findings may be probably explained by the judicious use of erythromycin or other contributing factors (20, 21). Nonetheless, high resistance against erythromycin was reported from other countries. For instance, 15.4% and 7.0% of the isolates were also resistant to erythromycin in Brazil and Spain, respectively (22, 23). Differences in the prevalence of macrolide-resistant GAS are commonly related to geographical area, type of circulating strains or clones, and types of study population. In addition, S. pyogenes in the present study remained susceptible to penicillin and vancomycin as reported by others (3, 5, 24).

As for the clindamycin resistance, all GAS isolates in the current study were also susceptible to this antibiotic. It is well understood that clindamycin has immune-modulatory properties and is commonly used for the treatment of severe GAS infections (25). Surprisingly, a high resistance rate for tetracycline (54.3%) was observed in the present study. In contrast, only 3.5% of GAS isolates were resistant to tetracycline in Spain (23). However, the current study result was in agreement with the reports on global rise of tetracycline-resistant GAS (26, 27). With regard to the resistance gene, the presence of mefA in an erythromycin-susceptible isolate in the current study is not surprising. Similar observations were documented in a study by Brenciani et al. in which tetM gene was found in tetracycline-susceptible isolates (28). It was proposed that the resistance genes could be present in a silence form (28). Nonetheless, further study is warranted to evaluate the significance of this finding in future.

Twenty different emm types were identified in the current study. However, no new emm types were observed. A wide diversity of emm types was observed with no dominancy of a single emm type in the current study. Similar observation was reported in United Arab Emirates (29). Interestingly, erythromycin-susceptible GAS isolates with emm types of 1, 12, 81, and 89 found in the present study were also observed by others (11, 30). In contrast to current study findings, emm types of 12 and 89 were associated with erythromycin resistance in few studies (31, 32). It is well understood that the distribution of emm types may differ according to geographical region. It is proposed that the specific genetic marker (emm pattern) could be related to tissue preference. With regard to this, emm pattern E (45.7%) and emm patterns A-C (20.0%) were identified from both invasive and non-invasive sites in the present study. The emm pattern E has no predilection to any specific tissue sites (33). In contrast to the current study findings, emm patterns A - C are usually related to throat carriage and non-invasiveness (33). Whereas, 9 (75.0%) out of 12 emm pattern D (skin specialist) were identified from the skin pus.

The emm types of 1, 12, 18, 28, 44, 71, and 81 found in the current study are amongst 25 most common emm types causing overall disease in Asia (34). More interestingly, 4 emm types (n = 6; 42.9% of total invasive sites) comprising emm1 (n = 1), emm12 (n = 1), emm18 (n = 3), and emm101 (n = 1) are usually linked to invasive disease in Asia (34). The crucial development of vaccine is based on the detection of predominant emm types among invasive GAS strains and the target population involved. To the authors’ best knowledge, it is the first study on the distribution of emm type in Malaysia based on emm typing. Thus, this may give little insight for the development of vaccine in future.

MLST analysis demonstrated eight predominant CCs with diverse STs among 21 isolates in the current study. The predominant STs among the representative isolates were as follows (in descending order): ST28/emm1 (CC1, 14.3%) and ST60/emm102 (CC58, 9.5%), while each of these singletons (ST318/emm71 and ST402/emm18) were represented by 9.5% of the isolates. The occurrence of the globally acknowledged groups such as the ST28/emm1 (CC1) found in both hospitals in the study is of particular concern as it is linked to invasive diseases (34). The emm89 with different STs consisting of ST101 and ST408 both under CC2 were observed in 9.5% of the isolates. Some emm types represented by two isolates each portrayed widely divergent genetic backgrounds. Amongst them, emm63 (ST426 and ST306) both singletons, differed at 4 of the 7 housekeeping loci, emm91 represented by ST5 (CC26) and ST13 (CC78) showed differences at 5 of the 7 loci. Isolates with emm types of 1, 18, 28, 71, and 102 in the present study shared identical or highly similar allelic profiles, also observed in other studies (26, 35). The study has several limitations. Limited types of emm could be due to the small number of isolates in the present study. Thus, the predominant emm types could not be considered as the basis for vaccine development in Malaysia.

6. Conclusions

Group A Streptococcus isolates found in the current study displayed high susceptibility towards erythromycin, which could be due to low antibiotic selection pressure in Malaysian clinical settings. High genetic diversity of GAS strains are observed by emm and MLST typing methods. The presence of ST28/emm1 (CC1) among the GAS deserves special attention due to its invasive characteristics. Thus, continuous epidemiological monitoring by molecular typing methods is warranted in future.