1. Background

Acinetobacter baumannii is responsible for a wide range of infections including upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, surgical wounds, bacteremia, meningitis, and life threatening infections (1). Acinetobacter baumannii is becoming a serious clinical concern due to the acquisition of a wide variety of antibiotic resistance genes and also environmental adaptation in various harsh environments. Over the past decades, regardless of new therapeutic options, A. baumannii strains have shown a remarkable ability to rapid development of multi-drug resistance (MDR). This rapid increase of MDR is not only due to the intrinsic resistant genes carried by these strains, but also to their outstanding capacity to acquire resistant elements from other bacteria (2).

Increasing levels of resistance to antimicrobial agents in nosocomial isolates of A. baumannii and also dissemination of MDR A. baumannii (MDRAB) have challenged health care. Most A. baumannii clinical isolates are now resistant to a wide range of antibiotics (3). In Acinetobacter spp., the acquisition and dissemination of an antimicrobial-resistant determinant in hospitals and community are frequently facilitated by horizontal gene transfer of mobile elements, including plasmids, transposons, and integrons. Among these mobile elements, integrons are considered unique for their capacity to carrying and expressing resistance genes (4, 5). Integrons are widely present in the genome of MDRAB, and has been documented to be relatively stable over a prolonged period of time (6).

Integrons are mobilizable platforms-DNA elements capable of spreading MDR particularly in Gram-negative pathogens. They are normally motionless but are contained in transposons and plasmids and can be transferred through these mobile genetic elements (4). The basic structure of integrons is composed of 5’and 3’-conserved segments with gene cassettes containing antibiotic resistance genes which can be inserted or excised by a site-specific recombination mechanism catalyzed by the integrase. The 5’-conserved region contains a promoter, PC, and an intI gene encoding integrase, and the 3’-conserved region consists of sequences derived from transposons (2).

To date, five main classes of integrons have been described upon the basis of the sequence identity of the int gene. Among these five classes of integrons, classes 1 and 2 integrons are the most frequently identified integrones in clinical isolates of A. baumannii. Reports on the other classes of integrons are scarce (4). According to literature, integrons, as the most prevalent integron type in capture and accumulation of many antibiotic resistance genes in A. baumannii clinical isolates, are useful tools for studying molecular epidemiology of nosocomial infectious outbreaks caused by this bacterium in critical wards of hospitals, such as ICU (7).

2. Objectives

Considering these points, the present study aimed to determine the occurrence of drug resistance, presence, and dissemination of different classes of integrons in A. baumannii isolates recovered from hospitalized patients in ICUs.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolates

Between October 2015 and April 2016, a total of 105 non-repetitive A. baumnnii isolates were obtained from 430 clinical specimens of hospitalized patients in ICUs of 4 medical centers located in different regions of Tehran. The research was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR-SBMU-1855). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients to use their samples for research purposes. Acinetobacter baumannii was identified using conventional biochemical tests and API 20 NE system (bioMerieux SA, Marcy-1’Etoile, France). Species identification was confirmed through detection of blaOXA-51-like gene as previously described (4, 7). The confirmed A. baumannii strains were stored at -70°C in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, Merck Co., Germany) containing 20% glycerol for further molecular investigation. Fresh isolates were sub-cultured twice on 5% blood agar plates (Merck Co., Germany) for 24 hours at 35°C prior to each experiment.

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Determinations

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) titer for 17 antibiotics including amikacin (AK), ampicilin/sulbactam (AMS), cefepime (FEP), cefotaxim (CTX), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftriaxone (CRO), ciprofloxacin (CIP), colistin (CS), gentamicin (CN), imipenem (IMI), meropenem (MRP), netilmicin (NET), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP), polymixin B (PB), tetracyclin (TE), trimetoprim- sulfamethoxazole (SXT), and tobramycin (TOB) was determined using E-test strips (Liofilchem, Italy) according to the clinical and laboratory standards institute guidelines (8). MDR was defined as resistance to 3 or more unique antimicrobial drug classes. Extensive drug-resistant (XDR) A. baumannii was defined as resistance to 3 or more unique antimicrobial drug classes and carbapenems (4). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as the control strain.

3.3. Extraction of DNA and Amplification of Integrase Gene

Chromosomal and plasmid DNA extraction was carried out using commercial standard kit InstaGene Matrix (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The presence of integron was screened in all the isolates using PCR with specific primers to conserved regions of integron-encoded integrase gene intI1, intI2, imtI3, as described by Japoni et al. (9). All primers were obtained by Cinnagene Co. (Tehran, Iran). PCR conditions for amplification of the integrase gene by thermocycler (Eppendorf co., Hamburg, Germany) were as follows: initial denaturation for 5 minutes at 94ºC, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94ºC for 30 seconds, annealing at 55ºC for 50 seconds, and extension at 72ºC for 45 seconds. The final extension was carried out at 72ºC for 5 minutes. The expected size of amplicon (491 bp) was ascertained through electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) prepared in TAE buffer. PCR product was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV transillumination (UVItec, Cambridge, UK).

3.4. Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism Analysis

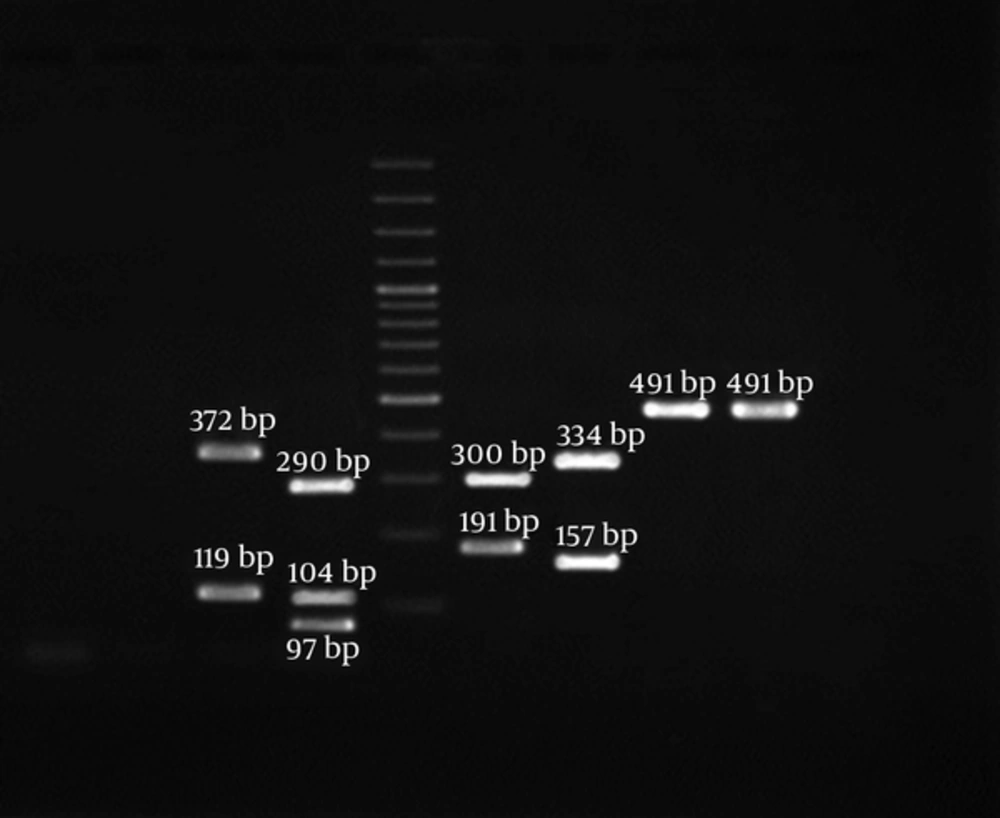

To detect integron classes, PCR positive products were digested using two restriction enzymes RsaI and HinfI and the resulting restriction patterns were analyzed through electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels (5). Restriction digests were carried out at 37°C in 20 µL volumes containing integrase PCR product (10 µL), appropriate buffer (2 µL), double distilled water (7 µL), and 1 µL of 10 U RsaI and HinfI. The size and number of generated fragments are given in Table 1.

| PCR Product | Enzyme | No. of Fragment | Fragment Size (s), bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Int I1 | Rsa I | 1 | 491 |

| Hinf I | 1 | 491 | |

| Int I2 | Rsa I | 2 | 334, 157 |

| Hinf I | 2 | 300, 191 | |

| Int I3 | Rsa I | 3 | 97, 104, 290 |

| Hinf I | 2 | 119, 372 |

RFLP Classification of Integrase PCR Products

4. Results

During the 7-month period of the study, a total of 105 A. baumnnii clinical isolates were obtained from different clinical specimens including wound (n = 65, 61.9%), blood (n = 25, 23.8%), catheter (n = 8, 7.6%), and cerebrospinal fluid (n = 7, 6.7%). The average age of the participants was 39 years (median 43.6 years, ranging from 1 to 61 years) and the age distribution was as follows: 25 patients were ≤ 20 years old, 76 patients 21 - 45 years old, and 4 patients ≥ 60 years old. Also, 74 patients (70.5%) were male and 31 (29.5%) were female.

4.1. Antimicrobial Resistance Profile

As given in Table 2, the highest levels of resistance were observed to be related to ciprofloxacin (96.2%) and gentamicin (80%) and the lowest levels of resistance were related to netilmicin (40%), trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole (43.8%), and meropenem (45.7%). The rates of resistance to other antibiotics tested were between 52% - 80%. Fortunately, all A. baumnnii strains were susceptible to colistin and polymixin B and inhibited at similar MIC50 and MIC90 1 µg/mL. Moreover, in vitro susceptibility of the A. baumnnii isolates to 17 antibiotics was tested; the ranges of MIC50 and MIC90 are shown in Table 2.

| Antibiotics | Integron Positive (N = 98) | Inetgron Negative (N = 7) | Total | MIC, µg/mL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | I | S | R | I | S | Resistance | 50% | 90% | |

| Ampicilin/sulbactam | 61 (62.2) | 0 (0) | 37 (37.8) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (42.9) | 65 (61.9) | 326 | 642 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 67 (68.4) | 0 (0) | 31 (31.6) | 6 (85.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 73 (69.5) | 128 | 256 |

| Cefepime | 58 (59.2) | 2 (2) | 38 (38.8) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) | 63 (60) | 64 | 64 |

| Cefotaxim | 74 (75.5) | 5 (5.1) | 19 (19.4) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (42.9) | 78 (74.3) | 128 | 128 |

| Ceftazidime | 55 (56.1) | 0 (0) | 43 (43.9) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (57.1) | 58 (55.2) | 32 | 64 |

| Ceftriaxone | 76 (77.5) | 4 (4.1) | 18 (18.4) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 83 (79) | 64 | 128 |

| Imipenem | 63 (64.3) | 0 (0) | 35 (35.7) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (71.4) | 65 (61.9) | 64 | 64 |

| Meropenem | 45 (45.9) | 3 (3.1) | 50 (51) | 3 (42.8) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 48 (45.7) | 16 | 32 |

| Gentamicin | 78 (79.6) | 5 (5.1) | 15 (15.3) | 6 (85.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 84 (80) | 64 | 64 |

| Amikacin | 80 (81.6) | 0 (0) | 18 (18.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 80 (76.2) | 32 | 64 |

| Netilmicin | 40 (40.8) | 4 (4.1) | 54 (55.1) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (71.4) | 42 (40) | 16 | 32 |

| Tobramycin | 48 (49) | 0 (0) | 50 (51) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 55 (52.4) | 16 | 32 |

| Tetracyclin | 59 (60.2) | 1 (1) | 38 (38.8) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) | 64 (60.9) | 32 | 64 |

| Polymixin B | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 98 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 | 1 |

| Colistin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 98 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 98 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (57.1) | 101 (96.2) | 16 | 32 |

| Trimetoprim- sulfamethoxazole | 40 (40.8) | 0 (0) | 58 (59.2) | 6 (85.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 46 (43.8) | 76 | 152 |

Antibiogram Results and Integron Frequency in A. baumannii Isolated from ICUa

According to the standardized definition of MDR strains, all the isolates exhibited the MDR pattern. A total of 75 isolates (71.4%) were XDR. The most common resistance pattern among the isolates studied was resistance to 7 antibiotics which were common in 37 (35.2%) isolates.

4.2. Detection and Typing of Integrons

Based on the results of the present study, the presence of integron was confirmed for 98 (93.3%) strains of A. baumannii. Of the 105 MDRAB strains, 70 (66.7%) and 21 (20%) isolates were identified as being positive for class 1 and class 2 integrons, respectively. Among the 105 tested isolates, 4 isolates (3.8%) were found to simultaneously carry class 1 and class 2 integrons. Surprisingly, for the first time in Iran, class 3 integron was observed in 3 MDRAB strains (2.9%).

Class 3 integron was distributed among isolates resistant to 14, 12, and 11 antibiotics. All the isolates harboring class 3 integron belonged to XDR isolates and the age group 21 - 45 years old. Co-existence of classes 1, 2, and 3 integrons was detected in two isolates one of which isolated from a 43-year-old HIV positive patient with bacteremia and another isolated from a farmer with wound infection. Co-existence of class 1 and class 3 integrons was detected in one isolate. PCR-RFLP products of the integrase gene are depicted in Figure 1. isolates (6.7%) did not harbor integrons. Distribution of different resistance patterns among MDRAB strains isolated from clinical samples of hospitalized patients in ICU is presented in Table 3.

PCR-RFLP of Integrase Gene Products. Lane 1, Hinf I Treated of Products Represent of Class 3 Integron; Lane 2, Rsa I Treated of Products Represent of Class 3 Integron; Lane 3, Hinf I Treated of Products Represent of Class 2 Integron; Lane 4, Rsa I Treated of Products Represent of Class 2 Integron; Lane 5, Rsa I Treated of Products Represent of Class 1 Integron; Lane 6, Hinf I Treated of Products Represent of Class 1 Integron; Lane M, 100 pb DNA Ladder

| Number of Drugs | Resistance Profile | Number of Isolates | Type of Integrons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | I, II | III | Without | |||

| 14 | CIP, IMI, CN, AK, CRO, CTX, TZP, AMS, TE, FEP, CAZ, TOB, MRP, SXT | 5 (4.8) | 2 (40) | - | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | - |

| 12 | CIP, IMI, AK, CRO, TZP, AMS, TE, FEP, TOB, MRP, SXT, NET | 9 (8.6) | 5 (55.6) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | - |

| CIP, IMI, CN, AK, CRO, CTX, TZP, AMS, TE, CAZ, MRP, SXT | 12 (11.4) | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | - | - | - | |

| 11 | CIP, IMI, CN, AK, CRO, CTX, TZP, AMS, TE, FEP, SXT | 8 (7.6) | 6 (75) | 2 (25) | - | - | - |

| CIP, CN, CTX, TZP, TE, FEP, CAZ, TOB, MRP, SXT, NET | 3 (2.9) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | - | - | |

| CIP, IMI, CN, AK, CTX, AMS, FEP, CAZ, MRP, SXT, NET | 5 (4.8) | 2 (40) | - | - | 1 (20) | 2 (40) | |

| 10 | IMI, CN,AK, CRO, CTX, TZP, AMS, FEP, TOB, SXT | 4 (3.8) | 3 (75) | - | - | 1 (25) | |

| CIP, IMI, CN, CRO, CTX, AMS, TE, FEP, CAZ, TOB | 15 (14.2) | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | - | - | ||

| 9 | CIP, IMI, AK, CTX, TZP, AMS, FEP, TOB, MRP | 7 (6.7) | 6 (85.7) | - | - | 1 (14.3) | |

| 7 | CIP, CN, AK, CRO, CTX, TE, TOB | 12 (11.4) | 6 (50) | 6 (50) | - | - | |

| CIP, CN, AK, CRO, TZP, CAZ, NET | 18 (17.1) | 15 (83.3) | - | − | 3 (16.7) | ||

| CIP, CN, CTX, TZP, FEP, MRP, NET | 7 (6.7) | 7 (100) | - | - | |||

Distribution of Different Classes of Integrons and Resistance Profile in A. Baumannii Isolated from ICUa

5. Discussion

The rapid expansion of A. baumannii clinical isolates exhibiting MDR pattern leads to difficulties in treating infections caused by this pathogen. Resistance to antimicrobial agents may be the main advantage of A. baumannii in causing large-scale nosocomial infectious outbreaks (7, 10). In the current study, all the isolates were MDR, which demonstrates a more serious situation of multidrug resistance. This finding is similar to those reported in previous studies in China (93.5%) (1) and Poland (100%) (2).

In the present study, 96.2% of the isolates were found to be resistant to ciprofloxacin. Our finding, compared to those of other studies, shows that resistance to ciprofloxacin is increasing among clinical A. baumannii isolates in Iran (2, 11). However, this is similar to the results in Al-Agamy who reported the resistance rate of 85% in A. baumannii collected from Egyptians (12). Much higher percentage (100%) was observed among A. baumannii isolated from ICUs in Iran (13).

In the present study, isolates resistant to aminoglycosides, such as gentamicin (80%), amikacin (76.2%), and tobramycin (52.4%), were frequently observed. In a study conducted by Nasr et al. (14), a high rate of resistance to amikacin (90%) and gentamicin (85%) was reported. Zhu et al. (15) reported that among 39 A. baumannii isolates tested, 33 (84.6%) were resistant to gentamycin and 32 (82.1%) were resistant to amikacin. In another study form Taiwan, the rates of resistance to gentamycin and amikacin were 57.5% and 56.7%, respectively (16). In the current study, it was found that 40% of MDRAB isolates were resistant to netilmicin. The prevalence of netilmicin resistance is very similar to that found in the study of Koczura et al. in Poland (2).

Resistance to carbapenems as drugs of choice for the treatment of infections caused by A. baumannii is increasingly being observed worldwide. In a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in Iran in 2016, Pourhajibagher et al. reported that 55% of A. baumannii strains were resistant to imipenem and 74% were MDR. They also expressed that MDRAB population in Iran is rapidly changing toward a growing resistance to imipenem (17). In the present study, the majority of the isolates (61.9%) were resistant to imipenem. This value is lower than the rates found in Turkey (80%) (18) and China (72.2%) (11) and higher than those reported in Iran (53%) (19), Russia (45%) (20) , Poland (41%) (2), Taiwan (36.6%) (16), and Nepal (36%) (3). The most probable reasons of imipenem resistance include improper prescription of this antibiotic in clinics, extensive misuse of carbapenems, and production of carbapenem hydrolyzing enzymes.

Although ampicillin/sulbactam has been proven to be more efficacious than polymyxins in treating carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii infection, high resistance to ampicillin/sulbactam in MDRAB isolates has been reported in many countries (21). In the present study, high resistance rates to ceftriaxone (79%), cefotaxime (74.3%), piperacillin/tazobactam (69.5%), ampicillin/sulbactam (61.9%), cefepime (60%), and ceftazidime (55.2%) were observed. As for the findings, the present study is consistent, to some extents, with the previous studies conducted in Egypt (14), Iran (4), Poland (2), Turkey (18), and China (11).

In MDRAB isolates studied, resistance to trimetoprim-sulfamethoxazole had relatively the lowest frequency (43.8%). In contrast, in a study conducted by Huang et al. (11) in China, resistance to trimetoprim-sulfamethoxazole was detected in 81.4% of A. baumannii isolates.

Colistin and polymyxin B are the last options for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii. Several studies from Iran reported colistin-resistant A. baumannii strains. In Vakili et al. study, colistin resistance in clinical isolates of A. baumannii was determined. They investigated 60 isolates of A. baumannii from ICUs and showed resistance to colistin in 7 isolates (11.6%) (22). In another study conducted in Iran in 2015, Sepahvand et al. investigated the susceptibility of 100 A. baumannii strains by E-test. Resistance to colistin was reported in 6% of isolates (23). In the present study, colistin retained its activity against all the MDRAB isolates, which is consistent with the reports of previous studies in Iran (4) and USA (24). High susceptibility rate to these antibiotics is likely because of its infrequent use due to its serious side effects.

Although the emergence of MDR pattern in A. baumannii isolates is extremely complicated, it could be linked to transposable elements (transposons, plasmids, and integrons) which can transfer resistance genes among bacteria. As mentioned, integrons are widely known for their role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance, particularly among Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. Class 1 integron, as the most prevalent class among mobile integrons in MDRAB clinical strains, has globally been confirmed. The present study demonstrated the detection of class 1 integron in 66.7% of A. baumannii clinical isolates that is in concordance with the rates reported from other geographical regains including Poland (63.5%) (2), and Taiwan (71.4%) (25), and yet is considerably higher than the rates reported from Turkey (6.4%) (18) and Iran (7.5%) (26). Much higher percentages were reported from Korea (89.3%) (27) and Egypt (85%) (12). However, in Iran, different frequency of resistance to imipenem has been reported, ranging from 7.5 to 93.3%, depending on location, type of A. baumannii isolates tested, and the time of the study (4, 26). This report highlights that class 1 integron is widely disseminated among MDR AB in the ICUs of hospitals in Tehran, Iran.

Although some studies explained the existence of class 2 integron among A. baumannii strains, only 21 MDRAB strains (20%) harbored class 2 integron in the current study. This result is in agreement with that reported in a study carried out on MDRAB in Brazil detecting class 2 integrons in 23% of isolates (6). In Taherikalani’s study (28) investigating the frequency of classes 1, 2, and 3 integrons among A. baumannii isolates in Tehran, the distribution of class 2 integron was reported in 14% of A. baumannii tested isolates. In contrast to the results of the present study that indicated the presence of class 2 integron in a limited number of MDRAB strains, this class was detected as the most frequent type in studies conducted by Kamalbeik et al. (67.5%) (26) and Mirnejad et al. (82%) (29). In contrast to the studies conducted in Iran (28), Thailand (30), Korea (27), China (11), and Poland (2), that did not detect any class 3 integron, in the current study, we found class 3 integron at a frequency of 2.9% in A. baumannii isolates, for the first time in Iran.

5.1. Conclusion

In summary, we observed a high level of A. baumannii strains harboring integrons in the hospitals studied, which can be used as an indicator to identify MDR isolates. Moreover, for the first time in the country, the present study revealed existence of class 3 integron among the isolates studied. Considering the role integrons play, as a genetic element, in horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes as well as MDR, the high frequency of integron in the current study can be due to the failure of treatments in patients. Still, further investigation should be conducted to study the epidemiology of integrons in different molecular types of A. baumannii.