1. Introduction

Polymyositis is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy that mainly occurs in adults. Polymyositis usually manifests itself with subacute proximal symmetrical muscle weakness. It may involve respiratory muscles contributing to respiratory insufficiency and aspiration pneumonia (1). Patients with polymyositis are also treated with immunosuppressive drugs (usually corticosteroids). As a result, they become susceptible to a broad spectrum of infections (2). Also, the literature has provided evidence that polymyositis is associated with several cancers (3). In this paper, we report concurrent pulmonary and cerebral lesions in a patient with polymyositis, whose diagnostic challenges are instructive for clinicians.

2. Case Presentation

A 56-year-old woman was referred to Labbafinejad Hospital (Tehran, Iran), complaining of productive cough and dyspnea from two weeks ago. Her symptoms gradually progressed until a sudden loss of consciousness occurred. She was a known case of polymyositis and was treated with oral prednisolone (12.5 mg daily) 18 months ago. The patient neither smoked nor consumed alcohol. On admission, the patient’s vital signs were as follows: Axillary temperature: 38.0°C, blood pressure: 110/70 mmHg, respiratory rate: 26 breaths/minute, the pulse rate: 90 beats/minute, and peripheral oxygen saturation: 87% on room air. The patient had a Glasgow coma scale of 13/15. Physical examination revealed only the use of accessory respiratory muscles.

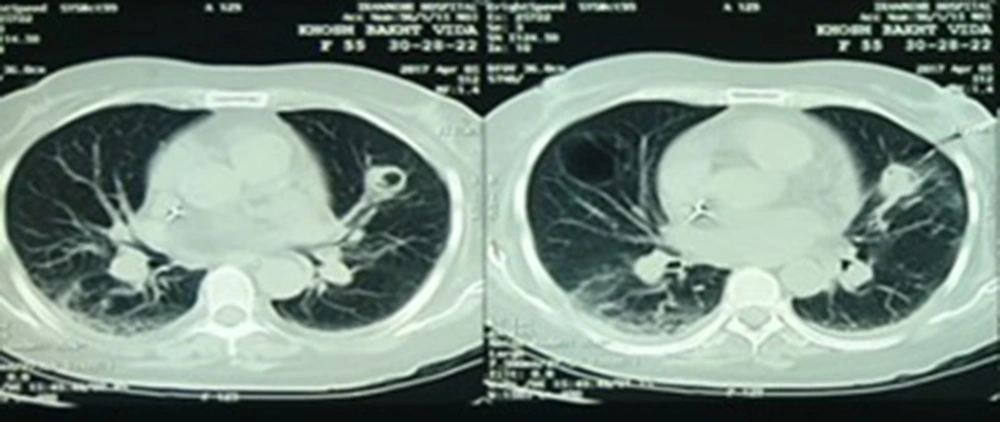

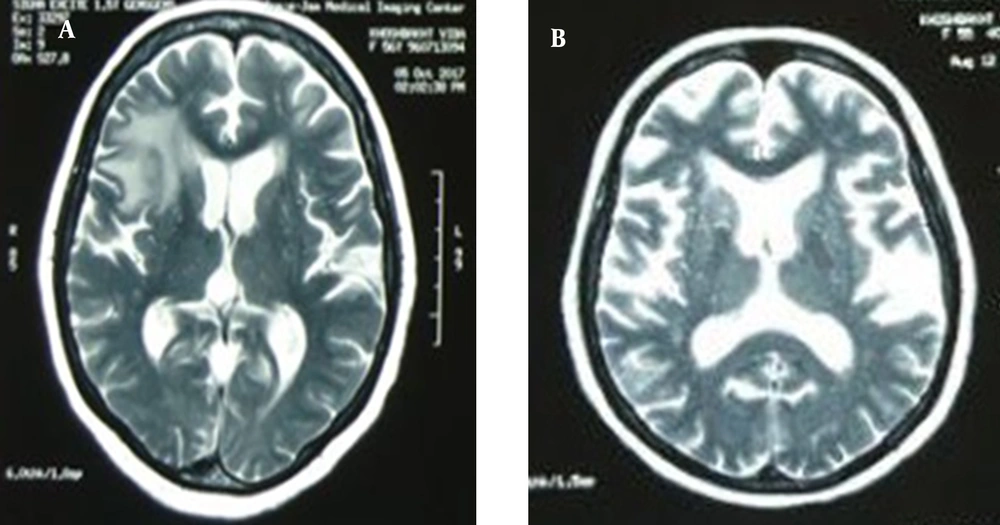

Laboratory investigation manifested Leukocyte count = 17700 cells/mm3 with 87% neutrophil, hemoglobin = 11.3 mg/dL, platelet count = 123000 cells/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) = 90 mm/h, C-reactive protein (CRP) = 103 mg/L, serum creatinine = 0.9 mg/dL, serum galactomannan = 0.1 optical density index, and negative blood culture. The lung computed tomography (CT) scan depicted a central cavitary mass lesion in the left upper lobe (with somehow thick walls and soft margins without calcification) and pleural thickening and adjacent reticular pattern airspace opacification in the right lung (Figure 1). Furthermore, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an area of increased signal intensity with surrounding edema in the right frontal lobe with a mild mass effect (Figure 2A).

Initially, the patient underwent empirical therapy with the following drugs: meropenem (500 mg every 8 hours), linezolid (600 mg every 12 hours), liposomal amphotericin B (0.25 mg daily), and hydrocortisone (50 mg every 8 hours). We administered the above antibiotics to cover bacterial and fungal etiologies of pyogenic brain abscesses. Also, because the patient’s general condition deteriorated, we changed the prednisolone (which the patient received daily) to a stress dose of hydrocortisone. During hospitalization, the patient did not respond to treatment. So, on the ninth day of hospitalization, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) were performed. Specimens obtained from TBLB revealed branched and septate hyphae. Besides, the culture of BAL specimens was positive for Aspergillus fumigatus (sensitive to voriconazole, itraconazole, and posaconazole; resistant to liposomal amphotericin B and caspofungin). As a result, we replaced intravenous voriconazole (6 mg/kg every 12 hours for the first day and 6 mg/kg every 12 hours for the next days) rather than amphotericin B. Then, the symptoms and level of consciousness improved dramatically. After three weeks of hospitalization, we discharged the patient in good general condition with oral voriconazole (200 mg every 12 hours).

At the follow-up three months later, the patient had no complaints while taking voriconazole. The lesions were cleared on a repeat lung CT scan. Amazingly, brain MRI illustrated an increase in the number and size of the lesions (Figure 2B). So, to explore the etiology of brain lesions, the patient was a candidate for stereotactic biopsy. Pathology findings confirmed an astrocytoma (grade III) in the right frontal lobe. According to the neurosurgery consultation, the patient did not indicate a surgical procedure. So, she was referred to radiotherapy.

3. Discussion

We report a known case of polymyositis with respiratory manifestations and an impaired level of consciousness. Imaging investigations revealed both pulmonary and cerebral involvement. Because the patient was treated with glucocorticoids for the long term, we considered her immunocompromised (4). Considering the lung and the brain involved simultaneously, we kept in mind the following infectious agents: Streptococcus angionosus, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Nocardia species, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Aspergillus species, Mucor species and Cryptococcus neoformans (5). Thus, we prescribed empirical and broad-spectrum therapy. After a few days of treatment, her symptoms did not improve. So, additional diagnostic measures explored invasive pulmonary infection (IPI) caused by A. fumigatus.

Aspergillus species are found in outdoor environments (e.g., soil and dust) and indoor environments (e.g., hospitals). Despite constant inhalation by humans, it does not cause disease in individuals with an intact immune system (6). Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), the most aggressive disease caused by it, mainly affects susceptible hosts. Patients with an impaired immune system (e.g., defects in neutrophil count or function, hematological malignancies, organ transplantation, and taking immunosuppressive drugs and corticosteroids) or underlying diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) have a higher risk of developing IPA (7, 8). Although there is no pathognomonic radiological sign of IPA, imaging is considered a diagnostic pillar. Imaging investigation of patients with IPA commonly presents nodules, halo sign, cavity, and air crescent sign. These findings, accompanied by clinical clues and laboratory findings, contribute to a diagnosis (9).

Due to the nonspecific manifestation of IPA in non-neutropenic patients, it can mimic bacterial pneumonia. For this reason, early diagnosis of IPA is generally a diagnostic challenge (10). Physicians should consider a blend of clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings to diagnose. In recent years, different methods have been introduced for the diagnosis of IPA. Galactomannan (one of the components of the cell wall of fungi) detection is the gold standard for diagnosing IPA (11). In non-neutropenic patients, galactomannan (at the cut-off level ≥ 1 optical density index) has higher diagnostic accuracy in BAL fluid compared with serum (12). The first-line treatment for patients with IPA is voriconazole or isavuconazole for 6 - 12 weeks. Although voriconazole is well tolerated, it may rarely develop visual disturbances, skin rashes, and abnormal liver enzymes. In terms of therapeutic efficacy, isavuconazole is not superior to voriconazole. Nevertheless, it has less cost and drug-related adverse reactions compared to voriconazole. When it is impossible to administer first-line drugs, liposomal amphotericin B or caspofungin may help. Combination therapy is not recommended except for refractory patients. Surgical interventions may be advantageous in patients with massive hemoptysis or refractory disease (7, 10).

Cerebral aspergillosis commonly presents with hypointense lesions on T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRIs (13). In contrast, the brain lesions of our patient were hypointense on T1 weighted and hyperintense on T2 weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR). It is a rare imaging finding of cerebral aspergillosis (14), which interestingly can mimic astrocytoma (15). Additionally, a brain biopsy is highly invasive and may cause neurologic deficits (16). Thus, assuming the identical etiology of pulmonary and cerebral lesions, we did not perform a brain biopsy and treated the patient with the diagnosis of aspergillosis. Gliomas are common tumors of the central nervous system. Anaplastic astrocytoma is a high-grade glioma that originates from astrocytes (17). It imposes considerable mortality and morbidity on affected adults, with a survival length of 2 - 5 years. Patients with grade III astrocytoma are commonly treated with surgical intervention, followed by chemotherapy or radiotherapy (18). The literature has provided evidence that pulmonary, renal, breast, bladder, endometrial, cervical, thyroid, and brain malignancies and lymphoma are associated with polymyositis (19). Although the mechanism of the increased risk of developing cancer in polymyositis patients is unclear, some studies attributed it to anti-transcriptional intermediary factor 1 (TIF1)-γ. Anti-TIF1-γ is an antibody produced against components of malignant cells, which has cross-reactivity with autoantigens. So, it can trigger some types of autoimmune myositis, including polymyositis (20).

3.1. Conclusions

Patients with polymyositis are prone to contracting opportunistic infections and malignancies. Both of them can mimic each other and present diagnostic challenges to physicians. Thus, it is important to consider them for early diagnosis and timely treatment.