1. Background

Bloodstream infection (BSI) is a major threat to patients in intensive care units (ICUs) (1). Bloodstream infection due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most serious nosocomial infections, with a mortality rate ranging from 8% to 50% (2-4). Pseudomonas aeruginosa is resistant to several antibiotics due to its intrinsic resistance and rapid acquisition of additional resistance mechanisms (5). As a result, the choice of appropriate antibiotics is difficult, and combinations of broad-spectrum antibiotics are usually used in early empirical treatment. This can lead to side effects and the development of antibiotic resistance (1).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to identify the clinical risk factors affecting mortality and the development of DTR-PA in patients with P. aeruginosa bloodstream infection. In the literature, there are differing results regarding the risk factors associated with mortality in patients with P. aeruginosa bacteremia (1, 2). The rate of antimicrobial resistance varies according to the local region and increases annually (6). Therefore, the geographic situation of antimicrobial resistance rates should be known and followed.

3. Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in a 100-bed adult ICU between January 2020 and December 2022. A total of 7,923 patients were followed up in the ICU during the study period. A confirmed case was defined as any patient who had BSI due to P. aeruginosa at least 48 hours after ICU admission. A total of 216 patients aged > 18 years were found to have P. aeruginosa growth in their blood cultures. A total of 76 patients were excluded because they developed P. aeruginosa bacteremia in the first 48 hours of ICU admission. A total of 140 patients were enrolled in the first clinical episode of BSIs.

3.1. Definitions

Bloodstream infections were identified by the presence of P. aeruginosa in one or more blood cultures. Secondary BSI and central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) were evaluated according to the definitions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (7). Pseudomonas aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance was defined according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023 Guidance (8). Appropriate empirical antimicrobial treatment was defined as receiving at least a new antimicrobial agent to which the pathogen was susceptible within the first 48 hours of blood culture (9).

3.2. Data Collection

Several clinical and epidemiological variables were studied using hospital electronic records: Age, gender, underlying diseases such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HT), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebrovascular disease (CVD), dementia, or malignancy, use of pulse steroid therapy for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), clinical conditions, invasive procedures, antibiotic use in the month before bacteremia, laboratory parameters, and patient outcomes. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) scores at the time of ICU admission were calculated for each patient (10, 11). The quick Pitt bacteremia score (qPitt) was calculated on the day the blood culture was drawn (12).

3.3. Laboratory Methods

Bacterial isolate identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed using the VITEK2 compact automated system (bioMérieux, France). Antibiogram evaluation was performed according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) standards (13).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS) version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to calculate the normal distribution. An independent samples t-test was used for normally distributed parametric data. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed parametric data. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical data. Cox regression analyses and logistic regression analysis were used to identify the risk factors associated with mortality and the development of DTR-PA BSI. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

During this study period, Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections (PA BSI) developed in 1.76% (140) of ICU patients. The mean age was (66 ± 17.5) years, and 48% of the patients were male. The most frequently observed comorbidity was HT (n = 61, 43.5%), followed by DM (n = 40, 28.5%) and CVD (n = 23, 16.4%). A total of 114 (81.4%) patients required invasive mechanical ventilation (MV), and 11 (7.8%) required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Inotropic support was initiated in 77 (55%) patients during bacteremia. A total of 73 (52.1%) patients were considered to have secondary BSI. A total of 43 (30.7%) patients had ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), 27 (19.2%) had catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), and 3 (2.1%) had surgical site infections. Central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) developed in 66 (47.1%) patients. A total of 90 (64.2%) P. aeruginosa strains were resistant to Carbapenem s. Colistin resistance was detected in 4 strains (2.8%).

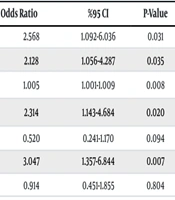

In this study, 62.8% of P. aeruginosa strains were classified as DTR-PA (n = 88). Univariate analysis revealed that mechanical ventilation, inotropic support requirement, central venous catheter use, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and meropenem and colistin exposure were significantly higher in BSI patients with DTR-PA (P = 0.028, P = 0.033, P = 0.027, P = 0.003, P = 0.019, P = 0.006, respectively) (Table 1). Logistic regression analysis revealed that CRP levels were significantly higher in DTR-PA BSI patients, and meropenem exposure was an independent risk factor for DTR-PA BSI [odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.00 to 1.01; P = 0.007, odds ratio, 2.68; 95% CI, 1.24 to 5.80; P = 0.012, respectively] (Table 2).

| Variables | DTR (n = 88) | Non-DTR (n = 52) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.36 ± 18.23 | 68.65 ± 16.25 | 0.285 |

| Gender; male | 41 (46.6) | 26 (50.0) | 0.696 |

| APACHE II score | 19.11 ± 9.21 | 20.37 ± 9.63 | 0.446 |

| CCI score | 3.79 ± 2.59 | 3.59 ± 2.61 | 0.660 |

| qPitt score | 3.0 (2.0 - 5.0) | 2.0 (2.0 - 3.0) | 0.098 |

| COVID-19 | 38 (43.2) | 18 (36.0) | 0.409 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 76 (86.4) | 37 (71.2) | 0.028 a |

| Inotropic support | 54 (62.8) | 23 (44.2) | 0.033 a |

| Central venous catheter | 84 (95.5) | 44 (84.6) | 0.027 a |

| Leukocyte count (/mm3) | 10060 (7310 - 15688) | 12000 (8400 - 16900) | 0.315 |

| C-reactive protein (0 - 5 mg/L) | 147 (84.8 - 224) | 100 (21.5 - 163) | 0.003 a |

| Procalcitonin (≤ 0.25 µg/L) | 1.05 (0.32 - 3.32) | 0.72 (0.30 - 2.84) | 0.526 |

| Antibiotic exposure | |||

| Meropenem | 60 (68.2) | 25 (48.1) | 0.019 a |

| Ceftriaxone | 19 (21.6) | 18 (34.6) | 0.091 |

| Piperacilin-tazobactam | 32 (36.4) | 20 (38.5) | 0.804 |

| Ceftazidime avibactam | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0.705 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 22 (25.0) | 7 (13.5) | 0.104 |

| Aminoglycosides | 4 (4.5) | 2 (3.8) | 0.844 |

| Colistin | 37 (42.0) | 10 (19.2) | 0.006 a |

| Appropriate empirical treatment | 45 (51.1) | 26 (50.0) | 0.705 |

| ICU length of stay (day) | 45 (27 - 66) | 33 (21 - 72) | 0.267 |

| 30-day mortality | 40 (45.5) | 22 (42.3) | 0.717 |

Abbreviations: DTR-PA, P. aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance; APACHE-II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; qPitt, quick Pitt; ICU, intensive care unit.

a P-value < 0.05.

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | %95 CI | P-Value | Odds Ratio | %95 CI | P-Value | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2.568 | 1.092-6.036 | 0.031 | |||

| Inotropic support | 2.128 | 1.056-4.287 | 0.035 | |||

| C-reactive protein | 1.005 | 1.001-1.009 | 0.008 | 1.006 | 1.002-1.010 | 0.007 a |

| Meropenem exposure | 2.314 | 1.143-4.684 | 0.020 | 2.683 | 1.240-5.804 | 0.012 a |

| Ceftriaxone exposure | 0.520 | 0.241-1.170 | 0.094 | |||

| Colistin exposure | 3.047 | 1.357-6.844 | 0.007 | |||

| Piperacilin-tazobactam exposure | 0.914 | 0.451-1.855 | 0.804 | |||

Abbreviations: DTR-PA, P. aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance; BSI, bloodstream infection; CI, confidence interval.

a P-value < 0.05.

In this study, 62 (44.2%) patients died within 30 days. The 30-day mortality rate due to BSIs with Carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (CR-PA) was 45.5%, whereas this rate was 45.4% for DTR-PA BSIs. Univariate analysis revealed that the presence of dementia, invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, inotropic support requirement, development of CLABSI, and qPitt score were significantly higher in deceased patients (P = 0.023, P = 0.033, P = 0.048, P < 0.001, P = 0.027, P = 0.012, respectively) (Table 3). The laboratory values of the patients on the day of blood culture collection were analyzed; CRP, procalcitonin, creatinine, and D-dimer levels were significantly higher, and platelet levels were lower in deceased patients (P = 0.038, P < 0.001, P = 0.041, P = 0.021, P = 0.007, respectively) (Table 3). Multivariate analysis revealed that the inotropic support requirement was an independent risk factor for 30-day mortality [hazard ratio, 2.50; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.33 to 4.68; P = 0.004] (Table 4).

| Variables | Survive (n = 78) | Non-survive (n = 62) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.53 ± 18.28 | 69.18 ± 16.32 | 0.119 |

| Gender; male | 37 (47.4) | 30 (48.4) | 0.911 |

| APACHE II score | 20.45 ± 10.29 | 18.48 ± 7.97 | 0.218 |

| CCI score | 3.58 ± 2.79 | 3.90 ± 2.30 | 0.473 |

| qPitt score | 2.00 (1.75 - 4.00) | 3.00 (2.00 - 5.00) | 0.012 a |

| Comorbidity | |||

| DM | 18 (23.1) | 22 (35.5) | 0.106 |

| Arterial HT | 34 (43.6) | 27 (43.5) | 0.996 |

| CHF | 7 (9.0) | 7 (11.3) | 0.650 |

| COPD | 6 (7.7) | 7 (11.3) | 0.466 |

| Chronic renal failure | 3 (3.8) | 2 (3.2) | 0.844 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 13 (16.7) | 10 (16.1) | 0.932 |

| Dementia | 6 (7.7) | 13 (21.0) | 0.023 a |

| Malignancy | 6 (7.7) | 6 (9.7) | 0.677 |

| Pulse steroid therapy (prednisolone) | 0.278 | ||

| None | 68 (87.1) | 48 (77.4) | |

| 250 mg | 9 (11.5) | 11 (17.7) | |

| 1000 mg | 1 (1.2) | 3 (4.8) | |

| COVID-19 | 32 (41) | 24 (40.0) | 0.903 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 58 (74.4) | 55 (88.7) | 0.033 a |

| Inotropic support | 32 (41.6) | 45 (73.8) | < 0.001 a |

| ECMO | 3 (3.8) | 8 (12.9) | 0.048 a |

| Central venous catheter | 69 (88.5) | 59 (95.2) | 0.160 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.06 ± 1.40 | 8.78 ± 1.40 | 0.238 |

| Leukocyte count (/mm3) | 9950 (7877 - 15335) | 12930 (8300 - 17000) | 0.196 |

| Platelet count (/mm3) | 239000 (153250 - 300500) | 165500 (91250 - 258000) | 0.007 a |

| C-reactive protein (0 - 5 mg/L) | 122.00 (50.50 - 166.00) | 150.50 (66.25 - 252.00) | 0.038 |

| Procalcitonin (≤ 0.25 µg/L) | 0.44 (0.19 - 1.74) | 1.96 (0.53 - 4.34) | < 0.001 a |

| Creatinine (0.5 - 0.9 mg/dL) | 0.67 (0.47 - 1.33) | 0.91 (0.57 - 1.40) | 0.041 a |

| D-dimer (< 0.5 µg/mL) | 1.97 (1.27 - 4.50) | 3.00 (1.79 - 6.95) | 0.021 a |

| Lactate (0.5 - 1 mmol/L) | 1.30 (0.90 - 2.10) | 1.80 (1.22 - 2.29) | 0.059 |

| DTR-PA | 48 (61.5) | 40 (64.5) | 0.729 |

| Source of BSI | |||

| VAP | 26 (33.3) | 17 (27.4) | 0.451 |

| CAUTI | 15 (19.2) | 12 (19.4) | 0.985 |

| CLABSI | 30 (38.5) | 36 (58.1) | 0.027 a |

Abbreviations: APACHE-II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; qPitt, quick Pitt; DM, diabetes mellitus; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; DTR-PA, P. aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance; BSI, bloodstream infection; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infection; CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; HT, hypertension.

a P-value < 0.05.

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | %95 CI | P-Value | Hazard Ratio | %95 CI | P-Value | |

| CLABSI | 1.649 | 0.990 - 2.748 | 0.055 | - | - | - |

| Inotropic support | 2.516 | 1.400 - 4.523 | 0.002 | 2.502 | 1.335 - 4.689 | 0.004 a |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.640 | 0.746 - 3.609 | 0.219 | - | - | - |

| ECMO support | 2.369 | 1.122 - 5.003 | 0.024 | - | - | - |

| qPitt score | 1.649 | 0.990 - 2.748 | 0.055 | - | - | - |

| Dementia | 1.856 | 1.004 - 3.430 | 0.049 | - | - | - |

| C-reactive protein | 1.002 | 1.000 - 1.004 | 0.020 | - | - | - |

| Procalcitonin | 1.020 | 1.000 - 1.040 | 0.045 | - | - | - |

| Creatinine | 1.472 | 1.127 - 1.923 | 0.005 | - | - | - |

| D-dimer | 1.040 | 1.005 - 1.076 | 0.023 | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infection; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; qPitt, quick Pitt.

a P-value < 0.05.

5. Discussion

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been associated with serious and life-threatening infections, especially in ICU patients (1). Previous studies have shown that P. aeruginosa exhibits high rates of resistance (6, 14, 15). The EUROBACT-2 international cohort study, which included 2,600 patients from 333 ICUs in 52 countries, revealed that DTR-PA was present in 10.1% of the PA BSI strains (1). In our study, DTR-PA isolates were found in a higher percentage of blood culture samples (62.8%). This may be attributed to problems with antimicrobial stewardship at our hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study revealed that P. aeruginosa is resistant to most antibiotics, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (14, 15). Among the 140 P. aeruginosa isolates in our study, the highest resistance rate was found in piperacillin-tazobactam (67.8%). The higher resistance rate for piperacillin-tazobactam may be related to its preference for empirical treatment in our ICU. Recent studies have demonstrated that P. aeruginosa species have a wide range of colistin resistance levels (0.8 - 15%) (6, 16, 17). However, we found that the isolated P. aeruginosa strains showed a lower percentage of colistin resistance (2.8%). This may be due to the avoidance of colistin use because of its risk of nephrotoxicity. However, colistin consumption increases when there is high Carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa.

In this study, univariate analysis revealed that prior meropenem and colistin exposure, invasive MV, inotropic support requirement, central venous catheter usage, and elevated CRP levels were significantly higher in patients with DTR-PA BSI, which aligns with findings from previous studies on CR-PA (3, 18). In the literature, many studies have shown that prior antibiotic use is a risk factor for the development of antimicrobial resistance (19, 20). Recent studies have also identified prior Carbapenem use as an independent risk factor for CR-PA (18, 21). Similarly, prior meropenem use was found to be an independent risk factor for DTR-PA BSI in our study. PA BSI is a major cause of mortality, particularly in ICU patients (1). In a recent study from Turkey, the 30-day mortality rate was 44.6% for patients with PA BSI and 48% for DTR-PA BSI in ICUs (22). Our study demonstrated a 30-day mortality rate of 45.4% due to DTR-PA. The all-cause mortality rate in our study was 44.2%, consistent with the results of previous studies (2, 3).

In our study, univariate analysis revealed that the presence of dementia, a higher qPitt score, CLABSI, MV, ECMO, inotropic support requirement, thrombocytopenia, and higher CRP, procalcitonin, creatinine, and D-dimer levels were associated with poor outcomes, similar to previous studies (3, 4, 22). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that the requirement for inotropic support was an independent risk factor for 30-day mortality. This finding may be primarily related to septic shock. The mortality rate is high in septic shock patients, and clinical symptoms such as oliguria, shortness of breath, enteral feeding intolerance, changes in consciousness, and coagulation disorders may rapidly progress to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (23). Additionally, septic shock has been identified as an independent risk factor for mortality in recent studies of patients with PA BSI (24, 25).

Our study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a total of 42 (30%) patients were admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of COVID-19. In the literature, there are studies showing that admission with a COVID-19 diagnosis and prior corticosteroid therapy were associated with PA BSI mortality (26-28). However, our study revealed that COVID-19 had no significant effect on mortality in PA BSI patients. Nevertheless, our study had several limitations. This retrospective study was conducted at a single medical center. We did not analyze the P. aeruginosa resistance mechanisms associated with the clinical presentation.

5.1. Conclusions

Our results revealed that prior meropenem exposure is an independent risk factor for the development of DTR-PA BSI. Additionally, the need for inotropic support was identified as an independent risk factor for 30-day mortality in this study. These findings highlight the urgent need for action to reduce P. aeruginosa infections in the ICU. Strengthening infection control measures and promoting rational antimicrobial use are crucial for reducing PA BSIs and improving patient outcomes.