1. Introduction

The prevalence of invasive fungal infections caused by emerging fungal pathogens has increased significantly over the last two decades. This trend can be attributed to several factors, including the rising incidence of malignancies across various populations and the significant increase in the number of patients undergoing organ transplantation, immunosuppressive therapies, chemotherapy, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and invasive medical procedures (1). However, diagnosing these emerging fungal infections is often challenging due to their resistance to conventional antifungal drugs and their frequent association with higher mortality rates.

Trichosporon spp. are emerging basidiomycetous yeasts that can cause both superficial and invasive infections (2). Trichosporon asahii is the most commonly isolated species in invasive trichosporonosis (3). However, in recent years, several other Trichosporon spp. have been reported as causative agents of invasive infections. Trichosporon coremiiforme is phylogenetically closely related to T. asahii (3, 4). While it has been isolated from the bloodstream in clinical samples, T. coremiiforme has been recognized as an opportunistic agent of invasive infections (4), primarily affecting cancer patients and those exposed to invasive medical procedures.

Most invasive Trichosporon spp. infections are thought to begin with colonization of mucosal or cutaneous surfaces. A break in the integrity of these surfaces then leads to the seeding of the bloodstream (5, 6). Such breaks can result from epithelial damage caused by chemotherapy or intravascular catheters (6). Antibiotics may also increase the incidence and extent of colonization and may contribute to the risk of human infections. The ability of Trichosporon species to form biofilms on implanted devices, the presence of glucuronoxylomannan in their cell wall, and their production of proteolytic and lipolytic enzymes are factors likely contributing to the pathogenicity of this genus and, consequently, to the progression of invasive trichosporonemia (3).

Disseminated trichosporonosis is increasingly reported worldwide, posing challenges to both diagnosis and species identification. In this report, we describe a recurrent vulvovaginal infection caused by T. coremiiforme in an immunocompetent patient with menorrhagia, identified using molecular methods.

2. Case Presentation

In July 2023, a 35-year-old woman with a BMI of 39.54 was referred to Babol Medical Center due to recurrent vulvovaginitis. The patient presented with symptoms including inflammation, pruritus, dyspareunia, and discharge. Her medical history included a preterm cesarean delivery in 2020 and an ovarian cystectomy in 2021 due to the sudden onset of lower abdominal pain. Ultrasound observations indicated a 31 mm cyst in the left ovary and a Nabothian cyst in the cervical stroma. The patient had no history of underlying diseases.

In the clinical examination of the vagina, inflammation of the cervix was observed, along with abundant white and mucous discharge in the vagina and cervix. The patient was prescribed 250 mg azithromycin capsules, 500 mg metronidazole tablets, and clindamycin and clotrimazole vaginal cream (Dalavag C) for one week. The patient's history indicated that, three months prior, she had presented with symptoms of menorrhagia and recurrent infections and was referred to Babol Medical Center. An ultrasound examination revealed cervical hypertrophy and right ovarian atrophy. A gynecologist conducted a vaginal examination and observed severe inflammation of the cervix and vagina, along with severe tenderness of the uterus in the adnexa.

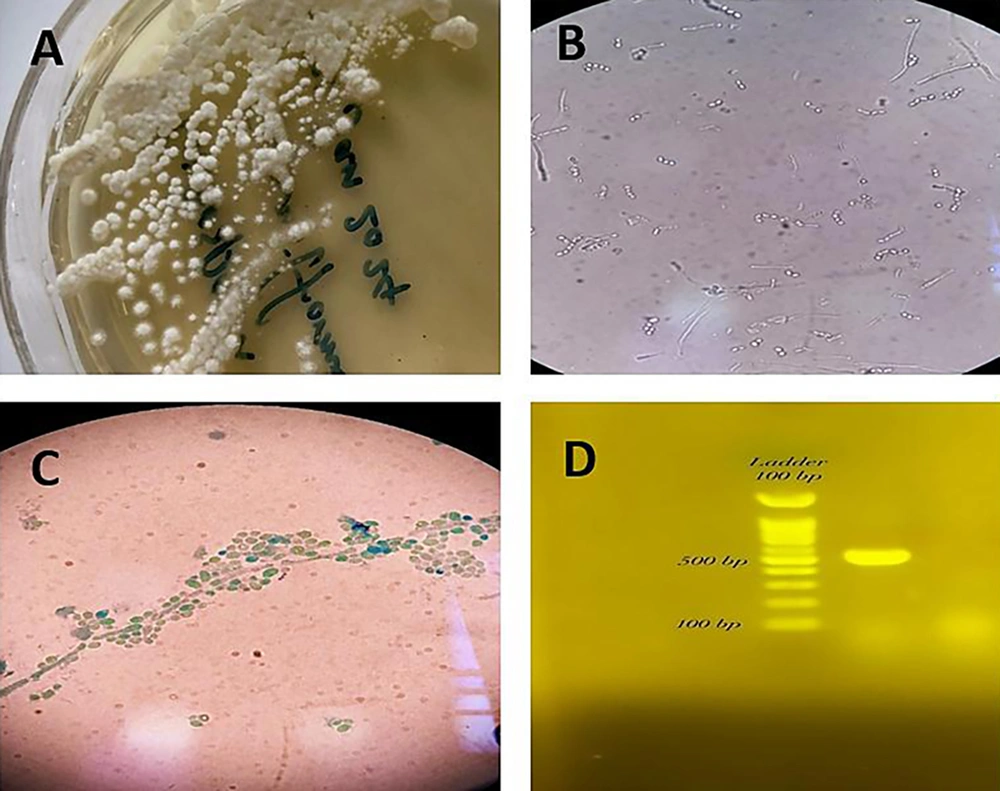

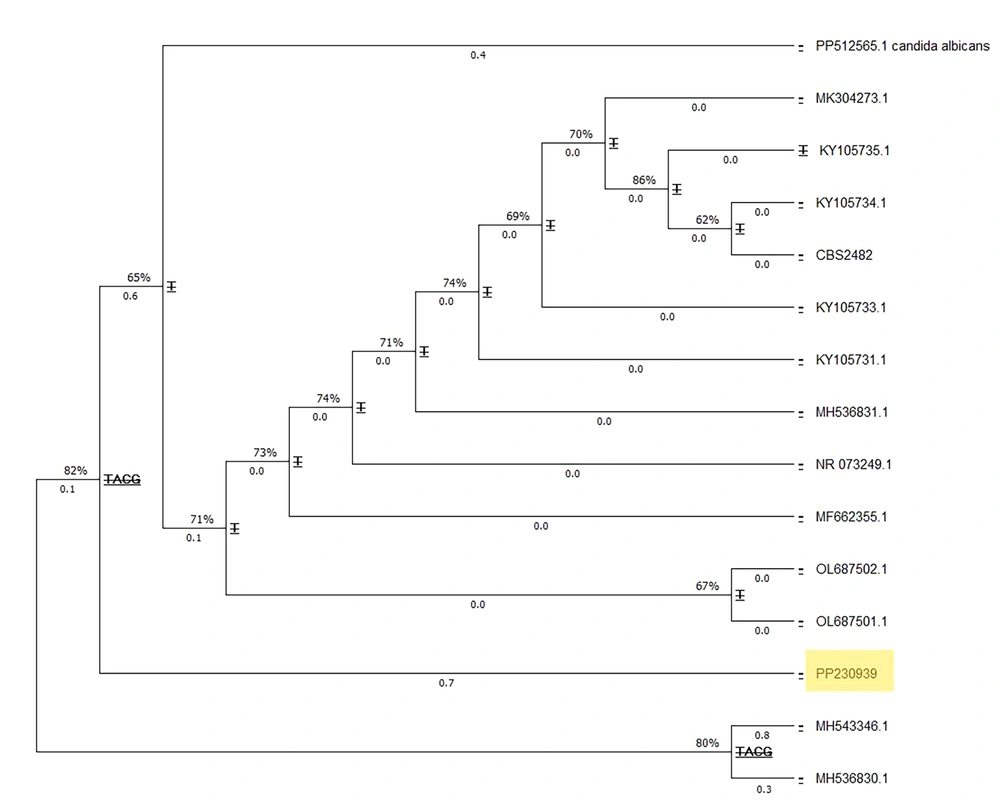

For clinical laboratory examination, the vaginal sample was stained with methylene blue and cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar medium (Merk, Germany) containing chloramphenicol (Sc). The culture media were incubated at 25°C and 37°C. Microscopic examination of the stained slides and the germ tube test confirmed the presence of numerous arthroconidia. The specimen was re-cultured on CHROM agar Candida medium (Merk, Germany), resulting in dark green colonies with a dry appearance. For precise molecular identification, the Colony PCR (7) reaction of the ITS region amplification was performed using primers ITS1 (5' TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG 3') and ITS4 (5' TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC 3'), and the DNA products were detected on a 1.5% agarose gel (Merk, Germany) (Figure 1). The PCR products were sequenced and then blasted using the NCBI database, with T. coremiiforme deposited in GenBank under accession number PP230939 (Figure 1). The closest matches to each sequence were determined using the BLASTN sequence similarity search tool in GenBank. Multiple alignments were performed with ClustalW using the default settings. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with MEGA11 using a maximum likelihood tree phylogram with the Tamura-Nei model. The confidence of branching was assessed through 500 bootstrap re-samplings. Candida albicans (GenBank accession number PP512565) was used as the outgroup (Figure 2).

A, Trichosporon coremiiforme on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar at 37°C after 4 days; B, arthroconidia and blastoconidia of T. coremiiforme in the sample inoculated with 0.5 mL of human serum; C, chains of arthroconidia from the hyphae and lateral blastoconidia at the sides of arthconidial chains or hyphae; D, electrophoresis results of the PCR products on 1.5% agarose gel.

In vitro, the antifungal susceptibility test was performed according to the recommendations stated in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-A4 guidelines (8, 9). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were ≥ 8 μg/mL for amphotericin B, 4 μg/mL for ketoconazole, 0.03 μg/mL for voriconazole, 4 μg/mL for miconazole, 4 μg/mL for fluconazole, and 4 μg/mL for clotrimazole. The patient was prescribed voriconazole 200 mg tablets daily for 20 days, levofloxacin 750 mg tablets (Tavanex) daily for 1 week, and miconazole 2% vaginal ointment for nightly use over 1 week. The patient returned to Babol Medical Center for a follow-up visit 20 days later. There were no signs of inflammation or itching, and the menorrhagia had completely resolved. The uterine examination was normal, with no inflammation or abnormal discharge in the cervix or vagina. To confirm healing, a sample of vaginal and cervical mucus was collected with a sterile swab and placed in saline. A liquid cervical smear was also taken and sent to the laboratory. The microscopic examination showed no evidence of fungal organisms. Negative mycological results were obtained from both vaginal and cervical mucus cultures. The Pap smear was also reported as normal.

3. Discussion

Trichosporon spp. is an emerging basidiomycetous yeast that can cause both superficial and invasive infections. This yeast-like fungus is characterized by morphological and physiological complexity and exhibits similarities to C. albicans. Like other dimorphic fungi, Trichosporon has the ability to grow as a budding yeast and develop filaments, which produce septate hyphae containing numerous arthroconidia and blastoconidia (1). The ability of Trichosporon to infiltrate the skin and various tissues relies on several virulent characteristics, such as the transition from yeast to hyphae, biofilm formation, enzymatic actions of lipases and proteases, and changes in the composition of the cell wall (10) (Figure 2).

These infections are most commonly found in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematological malignancies and neutropenia. Surgery and antibiotic use have been found to have a statistically significant association with higher rates of trichosporonosis. The genus Trichosporon is known to cause a variety of conditions, including white piedra, summer-type hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and various types of invasive infections. These invasive infections primarily affect individuals with compromised immune systems and can pose a significant risk to their lives. Despite antifungal treatment, the mortality rates for invasive trichosporonosis range from 42% to 90% (3).

Recently, Trichosporon spp. has been reported to cause invasive infections in humans; however, studies on vaginitis caused by Trichosporon spp. remain limited. Previous studies have shown that T. inkin is occasionally found in vulvovaginal cultures, though it is usually considered a nonpathogenic agent. Trichosporon species, such as T. asahii, are more commonly associated with systemic and invasive skin diseases, while T. inkin has been isolated primarily from genital specimens (2). Instances of T. coremiiforme have been documented in non-clinical samples, as well as in cases of summer hypersensitivity pneumonitis (SHP) caused by Trichosporon species in animals, and in nail and skin samples. It has also been successfully isolated from soil samples in Iran (10, 11). However, clinical cases of trichosporonosis caused by T. coremiiforme remain relatively rare (Table 1).

| Clinical Specimens | Method | Patients Age or Age Range/Gender | Origin | Associated Condition(s) | Therapy | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous abscess/urine | IGS1 region sequencing | NAa | Spain | NA a | NA a | NA a | (12) |

| Skin/nails | IGS1 and ITS region sequencing | NAa | Brazil | NA a | NA a | NA a | (13) |

| Bloodstream | IGS1 region sequencing | 10 days/female | Brazil | Pulmonary emphysema/pulmonary hypertension | Fluconazole | Survived | (6) |

| Bloodstream | MALDI-TOF MS | 15 - 49/male | Chin | NA a | NA a | NA a | (3) |

| Catheter-related bloodstream | MALDI-TOF MS | 46/female | Argentin | HIV/pulmonary tuberculosis/leukopenia/thrombocytopenia | Amphotericin B and fluconazole | Survived | (6) |

| Vaginal discharge | ITS region sequencing | 35/female | Iran | _ | Voriconazole and miconazole (vaginal oinment) | Survived | Current study |

a NA: Clinical and epidemiological data for patient were not available.

An important case report from 2019 documented the isolation of T. coremiiforme from a blood culture taken from an HIV-positive woman; however, there is no report of trichosporonosis caused by T. coremiiforme in vaginal samples. We report a case of vulvovaginal trichosporonosis in an immunocompetent patient. In this case, the resolution of symptoms was consistent with a previously positive vaginal culture for T. coremiiforme, which became negative after antifungal treatment. Transient colonization of Trichosporon species occurs mainly in African-American women with significant vaginal flora disturbances, such as bacterial vaginosis and increased trichomoniasis (14). The pathogenic consequences of Trichosporon colonization in the vagina appear to be very rare. Treatment should continue until a second culture shows persistence of Trichosporon species in a symptomatic patient in whom no other cause of symptoms has been identified (12). Accurate identification of opportunistic pathogens at the species level is crucial for understanding species-specific pathology and determining appropriate antifungal therapy (15).

Trichosporon species exhibit variations in their susceptibility to antifungal drugs, making precise identification necessary. Identifying the genus Trichosporon is essential for determining the best antifungal therapy because, like other Basidiomycete yeasts, it is intrinsically resistant to echinocandins (16). The fragment sequences of ITS1-5.8rRNA-ITS2 obtained in this study were found to be identical to sequences of T. coremiiforme and T. montevideense isolated from humans. This suggests that these isolates are pathogens that can be transmitted between humans. However, species identification in clinical laboratories remains a challenge because conventional identification methods are not reliable, and DNA-based methods are generally only available in reference laboratories (1, 2, 10).

In this study, the In vitro activity of six antifungal drugs on T. coremiiforme was tested, and azole drugs were found to be more effective than amphotericin B, which is consistent with other studies. Based on laboratory susceptibility, clinical eradication of T. coremiiforme should be followed by treatment with topical or oral azoles. According to Guo et al., voriconazole exhibited superior efficacy due to its requirement for the lowest concentration to inhibit growth (3) (Table 2).

| Sources (Human) | Minimium Inhibitory Concentration (μg/mL) | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB (S ≤ 1 μg/mL; R > 1 μg/mL) | FLU (S ≤ 8 μg/mL; R ≥ 64 μg/mL) | VOR (S ≤ 1 μg/mL; R ≥ 4 μg/mL) | ||

| Fecal material | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | (15) |

| Bloodstream | 1 | 1 | 0.03 | (6) |

| N/A | 8 | 0.25 | - | (1) |

| Blood | 0.5 | 4 | 0.06 | (3) |

| Blood and respiratory tract | 2 - 4 | 0.5 - 4 | 0.03 - 0.06 | (2) |

| N/A | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | (16) |

| Urine, subcutaneous abscess | 4.0 - 4.0 | 2.0 - 2.0 | 0.06 - 0.12 | (12) |

| N/A | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.03 | (16) |

| Vaginal discharge | ≥ 8 | 4 | 0.03 | Current study |

| TrichosporoncoremiiformeMIC range | 0.5 - 8 | 0.25 - 4 | 0.03 - 1 | - |

Abbreviations: AMB, amphotericin B; FLU, fluconazole; VOR, voriconazole; R, resistance; S, sensitive; MIC, minimium inhibitory concentration.

a N/A: Clinical and epidemiological data for patient were not available.

3.1. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of a vulvovaginal T. coremiiforme infection worldwide. Early diagnosis using accurate methods, such as PCR sequencing, and treatment with antifungal drugs like voriconazole or amphotericin B, is effective in managing such infections in patients.