1. Background

Meningitis is the infection and inflammation of the meningeal membranes in the brain and spinal cord. Headache is one of the prominent symptoms of this disease, but most patients are asymptomatic before the onset of systemic manifestations or only present with fever (1, 2). Prodromal symptoms of this disease include headache, sore throat, runny nose, cough, and conjunctivitis. With the onset of the severe phase of the disease, symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, myalgia, and arthralgia are also observed (3, 4). The causes of this disease are diverse, with infectious causes including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi (4-6). Despite significant advances in medical fields, the incidence of this disease has not decreased among people (1, 7). Meningitis is considered a medical emergency that requires rapid diagnosis and treatment; otherwise, it can lead to death and irreparable complications (3).

Escherichia coli K1, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Haemophilus influenzae are common bacterial causes of meningitis in infants and children (4, 7-9). In adults, Neisseria meningitidis and S. pneumoniae are jointly responsible for 80% of bacterial meningitis cases, although the risk of infection with L. monocytogenes increases in people over 50 years of age (5, 8, 10, 11). Although culture has been the gold standard for diagnosing meningitis infections in hospitals for many years, research today shows that nucleic acid-based methods are more sensitive. For instance, a retrospective study in 2019 on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples of individuals diagnosed with bacterial infections demonstrated that the frequency of infections was 95.8% using the molecular method and 31.9% using the culture method (12).

2. Objectives

The objective of this study is to utilize a molecular polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique to detect the causative bacterial agent of meningitis in CSF samples obtained from hospitalized patients suspected of having meningitis. The results obtained with this method will then be compared with the results of conventional culture used in Hamadan hospital laboratories.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

This study was conducted on 104 CSF samples from hospitalized patients suspected of having meningitis. Individuals were sampled prior to antibiotic consumption from February 2022 to August 2023. After coordinating with the hospitals of Hamadan province, 2 cc of CSF was transferred to the microbiology laboratory of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran, and used for DNA extraction and PCR. It should be noted that diagnostic procedures were also carried out using the culture method on the CSF samples in the hospital diagnostic laboratories.

3.2. DNA Extraction

The tubes containing CSF samples were subjected to a centrifugal process, after which the upper layer of the solution was discarded. The residual sediment was transferred into 1.5 mL microtubes for subsequent DNA extraction. The protocol for DNA extraction was executed in accordance with the guidelines established by the DNA extraction kit (Sina Clone Co, Tehran, Iran). Following PCR, the DNA samples were stored at -20°C.

3.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction

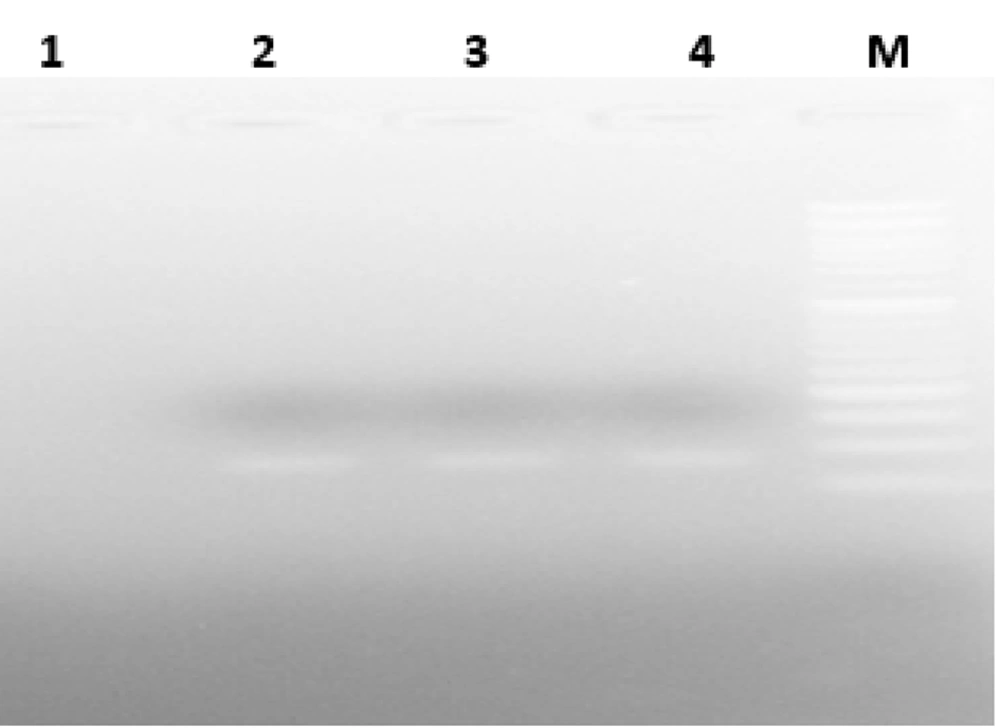

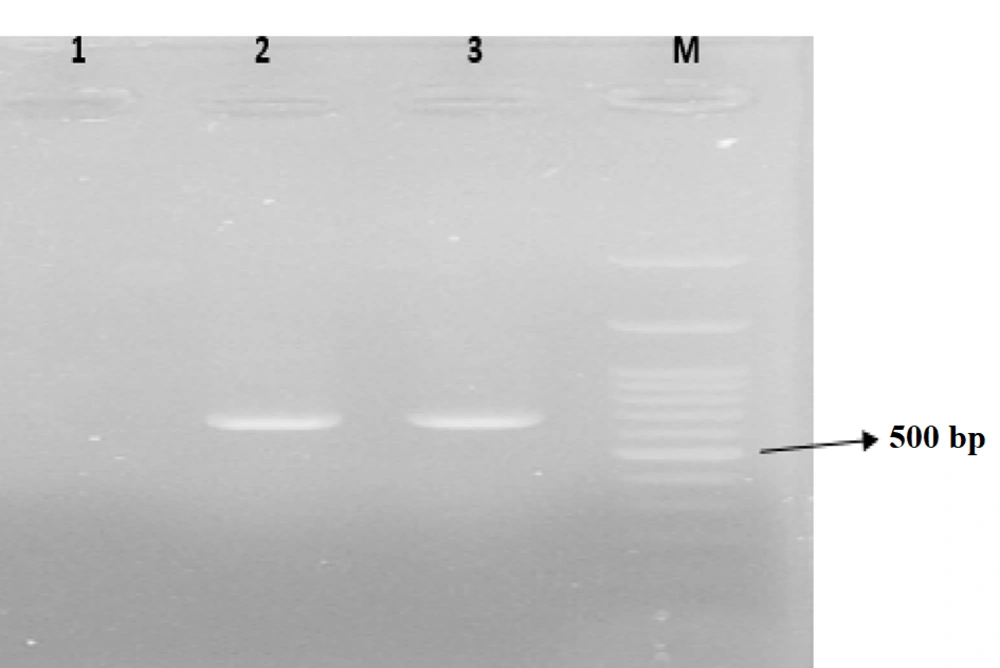

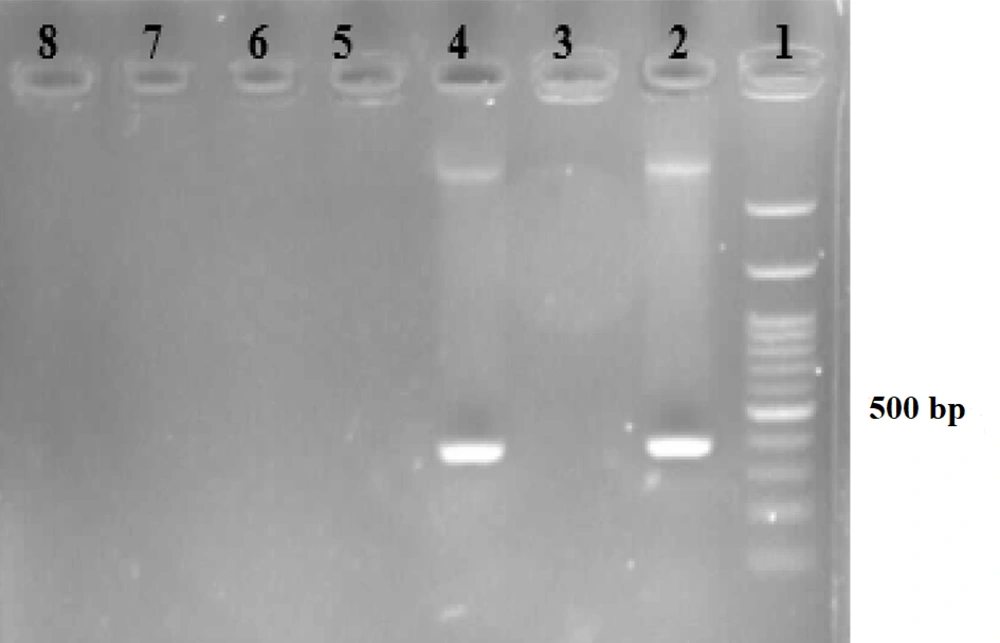

The desired reaction was performed (1-3) in a volume of 25 microliters of PCR Master Mix (Pars Tous Company, Iran) using the designed primers (Table 1). The product was then electrophoresed on an agarose gel and examined under UV light for the presence or absence of DNA bands for each bacterium (Figures 1 - 3).

| Bacterial | Reverse Primer (5’ - 3’) | Forward Primer (5’ - 3’) | Genes | PCR Product (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neisseria meningitides | TTGTCGCGGATTTGCAACTA | GCTGCGGTAGGTGGTTCAA | ctrA | 140 | (1) |

| Streptococcus pneumonia | CTCTTACTCGTGGTTTCCAACTTGA | TGCAGAGCGTCCTTTGGTCTAT | lytA | 81 | (1) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | CAATCCTAAGTATTTTCGGTTCATT | TAGGAACATGTTCATTAACATAGC | cpsL | 688 | (1) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | GGCCAAGAGATACTCATAGAACGTT | TATCACACAAATAGCGGTTGG | bex | 181 | (2) |

| Listeria monocytogenes | CAAAGAAACCTTGGATTTGCGG | GCTGAAGAGATTGCGAAAGAAG | hlyA | 370 | (3) |

| Escherichia coli K1 | TCTTTGAGCCTAGCTTCAACTGG | ATGGTGATGTTTCTGTTGGAGAAG | neuC | 150 | (1) |

Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Electrophoresis gel for amplification of hlyA gene in Listeria monocytogenes. Lane 1: 100 bp ladder; lane 2: Positive control for L monocytogenes (370 bp); lane 3: Negative control; lane 4: Positive sample polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for L monocytogenes; lanes 5 - 8: negative sample PCR for L monocytogenes.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data were entered into SPSS software version 22. Subsequently, the data were summarized in the form of tables, graphs, percentages, and averages.

4. Results

The mean age in this study was 31.57 ± 25.85 years. The oldest participant was 89 years old, and the youngest was 1 month old. The frequency of participants by gender included 53.85% males and 46.15% females. The highest frequency of specimens was from the neurology department at 30.77%, while the lowest frequency was from the neonatal department at 4.81%. In the context of hospital laboratories, no bacterial isolates were identified from the CSF samples examined by the culture method. However, PCR revealed the presence of bacterial infection in 5 (4.81%) CSF samples. The bacterial identifications made using the PCR method included L. monocytogenes (0.96%), S. pneumoniae (1.92%), and S. agalactiae (1.92%). The culture method yielded only one case (0.96%) of Staphylococcus epidermidis, which was not the objective of the study. The results are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

| Variables | Values a |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 25.85 ± 31.57 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 56 (53.85) |

| Female | 48 (46.15) |

| Inpatient department | |

| Neonatal | 5 (4.81) |

| Infants | 30 (28.85) |

| Neurology | 32 (30.77) |

| Neurosurgery | 29 (27.88) |

| ICU | 8 (7.69) |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

| Bacterial | PCR | Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Neisseria meningitides | 0 | 0 |

| Escherichia coli K1 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 2 (1.92) | 0 |

| S. pneumonia | 2 (1.92) | 0 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 0 | 0 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 1 (0.96) | 0 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | - | 10 (9.6) |

Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

The mortality rate associated with bacterial meningitis varies based on the treatment modality, the age of the patient, and the primary etiological factor. For infants, the mortality rate following a single episode of bacterial meningitis ranges from 20% to 30%. This risk is much lower in older children, with mortality reaching about 2%, but it increases again in adults, reaching 19 - 37% (7, 9). The incidence of this disease in newborns in developed and Western countries is 0.2 - 0.5%, while in developing countries, it is 1.1 - 1.9% (13, 14). In the present study, the prevalence rate of common bacteria causing meningitis by the PCR method was 5 (4.81%) cases, while the frequency of detection of these bacteria by the culture method was 0.96%.

A meta-analysis study in Iran investigating the prevalence of acute bacterial infections in meningitis patients reported the prevalence of N. meningitidis infection as 13%, H. influenzae type B as 15%, S. pneumoniae as 30%, and coagulase-negative staphylococci as 14% (15). In 2019, Pourmohammed et al. conducted a study to detect the frequency of bacterial infections in CSF samples of children hospitalized in a Tehran Hospital. Using the PCR method to analyze 119 samples, they documented the prevalence of N. meningitidis, H. influenzae type b, and S. pneumoniae infections as 11, 10, and 7 cases, respectively. The researchers concluded that nucleic acid-based bacterial infection tests exhibit heightened sensitivity and accuracy (16).

In 2019, Sharma et al. investigated bacterial infections in CSF samples in Nepal. They examined the CSF samples of 384 individuals to determine the prevalence of N. meningitidis, H. influenzae type b, and S. pneumoniae using both culture and PCR methods. The culture method revealed frequencies of 2.34%, 2.08%, and 3.13% for N. meningitidis, H. influenzae type b, and S. pneumoniae, respectively. The PCR method yielded similar results, with frequencies of 2.34%, 3.13%, and 3.13%, respectively. The study concluded that molecular methods are more sensitive for detecting bacterial infections, underscoring the importance of meningitis detection (17).

In 2014, Attarpour et al. investigated bacterial infections in 182 CSF samples in Iran, aiming to determine the prevalence of N. meningitidis, H. influenzae type b, and S. pneumoniae. The study's findings indicated frequencies of 14%, 26%, and 36%, respectively, suggesting that immunization with a vaccine can be effective in reducing these infections (18). In a 2021 study by Peletir et al., the prevalence of bacterial infections was investigated in CSF from Nigeria. They performed a multiplex real-time PCR test on the CSF samples of 210 people to ascertain the prevalence of bacterial infections. The prevalence of N. meningitidis, H. influenzae type b, and S. pneumoniae infections was 67.1%, 2.3%, and 3.4%, respectively. These results were consistent with those of other studies, which concluded that the molecular method is more sensitive and accurate in detecting bacterial meningitis infections (19).

In 2021, Hemmati et al. conducted a study to investigate bacterial infections causing meningitis. They tested CSF samples from 212 individuals using a multiplex quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method. The study's findings revealed the prevalence of specific bacterial infections, including N. meningitidis, E. coli K1, S. pneumoniae, and S. agalactiae, with observed frequencies of 28, 17, 15, and 21 cases, respectively (20).

The findings of our study, when compared to those of other research, indicate a minimal prevalence of bacterial agents responsible for meningitis in CSF samples. However, a crucial point that merits further investigation is the accurate diagnosis of meningitis by clinical experts, given the results. The findings of this research indicated that a significant proportion of the patient samples exhibited an absence of bacterial infection. Given the logistical challenges associated with CSF sampling in patients, it is imperative that clinical experts exercise greater caution when interpreting symptoms to ensure an accurate diagnosis of meningitis. In light of the low frequency of bacterial infections observed in this study, it is imperative to consider the role of viral agents in the diagnosis process. However, a notable limitation of our study was the inability to detect other potential infectious agents of meningitis, such as viruses and protozoa, due to constraints in financial resources. The results of our study, in conjunction with those of other research groups, indicate that clinical experts should prioritize the diagnosis of infectious agents using more precise methods, such as molecular techniques, for more accurate diagnoses.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of this study showed a low prevalence of common bacterial infections in CSF samples and demonstrated that the molecular method is more accurate and sensitive for detecting these bacteria compared to culture. It is recommended that PCR be performed simultaneously with CSF culture, which, when considered in the context of the patient's clinical symptoms, can serve as a diagnostic guide for medical professionals.