1. Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a gram-negative bacterium that frequently causes opportunistic infections in humans. Pneumonia, sepsis, diarrhea, liver abscess, endophthalmitis, meningitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and bacteremia are several infections caused by K. pneumoniae. Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia (MDR-KP) strains are an important cause of community- and hospital-acquired infections. The MDR-KP often exhibits resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins [mainly associated with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)], carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones (1). Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKp) is often associated with the production of carbapenemase genes blaOXA-48 and blaKPC, as well as the metallo-beta-lactamase gene blaNDM, which has recently increased throughout the world, mainly due to the excessive use of carbapenem, restricting the effectiveness of treatment regimens (2). Polymyxins (polymyxin B and colistin) are the last drugs of choice for the treatment of severe CRKp infections (3).

In recent years, the growth of colistin-resistant (ColR) isolates has dramatically increased due to the widespread use of colistin in livestock and humans (4). The ColR CRKp isolates are the major cause of high mortality (69%) in blood infections induced by this bacterium, posing serious treatment challenges for physicians (5). The mechanism of resistance to colistin occurs in two ways: One, mutations in the chromosome, and two, acquisition of plasmid mcr genes (6, 7). Estimating the prevalence of resistance to colistin as a last-resort treatment option in a hospital in Tehran at different times can lead to epidemiological information that will help control and prevent its spread in the future.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed at determining the frequency of cephalosporin, carbapenem and colistin resistant and in addition the prevalence of ESBL, carbapenemas, and mcr-1 genes in K. pneumoniae isolates from patients admitted to a hospital in Tehran, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Specimen Collection and Identification

This cross-sectional study was conducted in a referral care hospital with more than 1,000 beds in Tehran, during March 2020 to February 2021. A total of 380 K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from hospitalized patients in different age groups and wards. The biochemical identification of K. pneumoniae isolates were performed by using biochemical tests (8).

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Isolates of K. pneumoniae from hospitalized male or female patients (all ages) from all hospital wards were included. K. pneumoniae isolated from outpatients and duplicate isolates from the same patient were excluded. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran before commencement of the study. Clinical information of the isolates was collected and recorded in a Microsoft Excel database. The isolates were coded to facilitate cross-referencing between samples. Though, no patient names were supplied.

3.3. Identification of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates

All K. pneumoniae isolates were screened for ESBL production using cephalosporins including cefotaxime (CTX; 30 µg). Then potential of K. pneumoniae isolates (CTX resistant isolates) for the production of ESBL were confirmed by the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) recommended combined disk test using CTX (30 μg), cefotaxime/clavulanate (CTX/CTL; 30/10 μg) and ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftazidime/ CTL (30/10 μg) (9).

3.4. Identification of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolate

Non-susceptibility of K. pneumoniae isolates to any of the carbapenems, including imipenem (IMI; 10 µg), meropenem (MEM; 10 µg), and ertapenem (ETP; 10 µg), was defined as CRKp isolates based on CLSI 2024 criteria (10). Phenotypic confirmation of CRKp isolates was conducted by the Carba NP test according to CLSI guidelines (10). Briefly, solution A contains 0.5% phenol red solution and 10 mM ZnSO4 solution was prepared. Solution B was made by adding 10 mg/mL IMI-cilastatin to solution A. The bacterial mass was directly suspended in both tubes containing 100 µL of 20 mM Tris-HCl lysis. Then, 100 µL of solution A was added, and the steps were repeated with 100 µL of solution B. The tubes were incubated at 37°C. Isolates giving any coloration change (yellow or light yellow) were interpreted as a positive result.

3.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates

The antimicrobial susceptibility of all CRKp isolates was determined using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method as recommended by CLSI 2024 (10) for the following antibiotics (Mast Co., UK): Levofloxacin (LVX; 5 µg), cefepime (FEP; 5 µg), ciprofloxacin (CIP; 5 µg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT; 1.25/23.75 µg), doxycycline (DOX; 30 µg), tobramycin (TOB; 10 µg), amikacin (AN; 30 µg), aztreonam (ATM), and piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP; 100/10 µg). Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 was used as a quality control strain.

3.6. Carbapenem Minimal Inhibitory Concentration Determination of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates

The MIC values (μg/mL) of the CRKp isolates for IMI (Merck, Sharp and Dohme Corporation, West Point, PA, USA) were determined by the E-test method and were interpreted according to CLSI guidelines (10).

3.7. Colistin Susceptibility Determination of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates

The MIC of colistin (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO, USA) was obtained by the broth microdilution method (11). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Proteus mirabilis ATCC 12453 were employed as control strains. The susceptible MIC breakpoint for colistin against Enterobacteriaceae is > 4 𝜇g/mL, and the isolates with MIC > 4 were considered as ColR (11). Therefore, CRKp isolates were grouped into ColR CRKp vs. ColS CRKp isolates.

3.8. Molecular Detection of Resistant Genes

Genomic DNA of CRKp isolates was extracted by the boiling method (9). The quality of the DNA was confirmed using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Roskilde, Denmark), and the ratio of absorbance at 260/280 nm was calculated. The ESBL encoding genes were recognized by sequential PCR using specific primers for the blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, blaKPC, blaNDM, blaOXA-48, blaIMP, blaVIM, and mcr-1 genes (12-18). The PCR products were sequenced, and the obtained sequences of the amplified target sites were aligned and compared with those in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information database, with the aid of the BLAST program. Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 7881 and K. pneumoniae ATCC BAA-1706 were utilized as positive and negative control strains, respectively.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

The analyses of all data were performed using SPSS software (version 20.0). The characteristics of isolates were compared by Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. In all experiments, the threshold for statistical significance was P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. General Clinical Characteristics

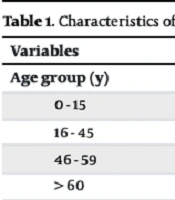

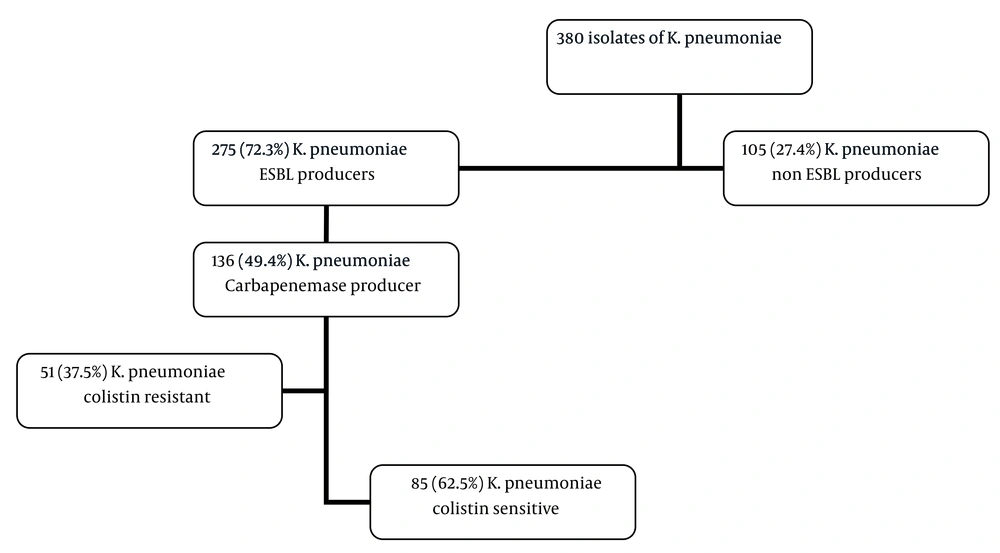

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 380 K. pneumoniae isolates were collected in this study. Two hundred twenty-seven (58%) of the patients were aged 60 years or older, and the remaining were below that age (40.2%). Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were mostly obtained from clinical samples of urine (n = 141, 37%). One hundred eighty-three (48.2%) isolates were recovered from patients who were in the ICU. Among the 380 isolates of K. pneumoniae collected in this study, 275 (72.3%) isolates had resistance to cephalosporins and were confirmed as ESBL producers. Among the 275 K. pneumoniae isolates, 136 (49.4%) were CRKp with MIC of the IMI ranging from 4 to 32 μg/mL. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants with K. pneumoniae infection (CRKp and CSKp). Of the 136 CRKp, these were more frequently isolated from women (n = 77, 57%); patients over 60 years (n = 84, 62%); urine samples (n = 49, 36%); patients in the ICU (n = 87, 63.9%); patients who utilized urinary catheters (n = 65, 48%); and those with cardiovascular diseases (n = 53, 72%). As illustrated in Table 1, there were no statistical differences between the CRKp and CSKp groups in terms of gender, age, distribution of specimens, and type of infection. ICU admission, utilization of invasive medical devices such as central venous catheters and urinary catheters (P ≤ 0.001 and 0.013), presence of underlying diseases such as diabetes and cancer (P ≤ 0.001 and 0.001), previous hospitalization (P ≤ 0.001), and antibiotic usage including carbapenems and macrolides (P ≤ 0.001) were significantly associated with CRKp infection.

| Variables | Total (N = 380) | CRKp (N = 136) | CSKp (N = 244) | P-Value | Odds Ratio (95%) Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (y) | |||||

| 0 - 15 | 14 (27) | 4 (3) | 10 (4) | 0.565 | 1.33 (0.32 - 5.48) |

| 16 - 45 | 21 (5.5) | 9 (6) | 12 (5) | 0.487 | 1.00 (0.39 - 2.59) |

| 46 - 59 | 118 (31) | 39 (28) | 79 (32) | 0.265 | 0.88 (0.56 - 1.39) |

| > 60 | 227 (58) | 84 (62) | 143 (58) | 0.547 | 1.06 (0.71 - 1.58) |

| Female | 228 (60) | 77 (57) | 151 (62) | 0.315 | 0.41 (0.11 - 0.54) |

| Distribution of specimens | |||||

| Tracheal aspirates | 37 (10) | 8 (9) | 29 (11.8) | 0.06 | 0.80 (0.36 - 1.79) |

| Urine | 141 (37) | 49 (36) | 92 (37.7) | 0.746 | 0.96 (0.69 - 1.33) |

| Sputum | 112 (29) | 40 (29) | 72 (29.5) | 0.984 | 1.00 (0.71 - 1.40) |

| Catheter | 22 (6) | 7 (5.1) | 15 (6.1) | 0.441 | 1.20 (0.46 - 3.15) |

| Blood | 26 (7) | 13 (9.5) | 13 (5.3) | 0.117 | 1.81 (0.71 - 4.52) |

| Broncho alveolar lavage fluid | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | 0.929 | 1.14 (0.06 - 20.21) |

| Tissues | 10 (2.5) | 4 (3) | 6 (2.4) | 0.778 | 1.25 (0.38 - 4.10) |

| Throat | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | 0.929 | 1.14 (0.31 - 5.21) |

| Synovial fluid | 3 (0.7) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0.929 | 1.75 (0.29 - 10.53) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | 10 (3) | 4 (3) | 6 (2.8) | 0.778 | 1.20 (0.38 - 3.72) |

| Pleural fluid | 7 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (1.6) | 0.679 | 1.38 (0.34 - 5.48) |

| Wound swab | 6 (1.5) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (0.8) | 0.872 | 3.63 (0.73 - 18.00) |

| Type of unit | |||||

| ICU | 183 (48.2) | 87 (63.9) | 96 (39.3) | 0.002 | 2.44 (1.39 - 4.28) |

| Surgical ward | 97 (25.5) | 31 (22.8) | 66 (27.1) | 0.751 | 0.82 (0.46 - 1.46) |

| Emergency | 59 (15.5) | 12 (8.9) | 47 (19.2) | 0.654 | 0.42 (0.20 - 0.89) |

| Pediatric | 31 (8.2) | 4 (3) | 27 (11.1) | 0.138 | 0.26 (0.07 - 0.94) |

| Other | 10 (2.6) | 2 (1.4) | 8 (3.3) | 0.112 | 0.41 (0.06 - 2.32) |

Characteristics of Patients in the Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and CSKP Groups a

4.2. Characteristics of Antibiotic Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates

The prevalence of blaCTX-M, blaSHV, and blaTEM in ESBL-producing isolates was 68% (n = 198/275), 52.3% (n = 144/275), and 35.2% (n = 97/275), respectively. In CRKp isolates, the antibiotic resistance pattern showed that COL (62.5%), AN (39%), and TZP (49%) are the options for the treatment of severe infections based on the antibiotic resistance pattern. Eighty-five (62.5%) isolates were ColS, while 51 (37.5%) were ColR. The range of MIC of colistin in 51 isolates was 16 to 32. As depicted in Table 2, in both ColR and ColS isolates, the highest antibiotic resistance was against FEP, SXT, CIP, and LVX, and the lowest resistance was against AN and TZP. The PCR of the ESBL genes in 275 ESBL-producing isolates showed the prevalence of blaCTX-M, blaSHV, and blaTEM were 68% (n = 198/275), 52.3% (n = 144/275), and 35.2% (n = 97/275), respectively. In addition, blaCTX-M (n = 122, 90%) was the most common gene in CRKp isolates. Detection of carbapenemase genes using specific primers in the CRKp isolates indicated that blaOXA-48 was the most dominant gene (n = 79, 58%). However, blaKPC, blaIMP, and blaVIM genes were not detected in any of the CRKp isolates. Among CRKp isolates, 48% (n = 65) harbored both blaOXA-48 and blaNDM genes. Regarding carbapenemase genes, the prevalence of the blaNDM gene was significantly higher in ColR (35%) than in ColS (20%) isolates (P = 0.038).

| Characters | CRKp Isolates | Colistin Resistance CRKp Isolates | Colistin Susceptible CRKp Isolates | P-Value c | Odds Ratio (95%) Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of isolates | 136 | 51 | 85 | - | - |

| Female | 77 (57) | 30 (59) | 47 (55) | 0.688 | 0.82 (0.46 - 1.47) |

| Deceased | 73 (54) | 29 (57) | 44 (52) | 0.625 | 0.87 (0.48 - 1.56) |

| Age group (y) | |||||

| 0 - 15 | 4 (3) | 3 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.148 | 3.00 (0.30 - 30.00) |

| 16 - 45 | 9 (6) | 5 (10) | 4 (5) | 0.209 | 1.25 (0.31 - 5.13) |

| 46 - 59 | 39 (28) | 13 (25) | 26 (30) | 0.06 | 0.48 (0.24 - 0.95) |

| > 60 | 84 (62) | 30 (59) | 54 (63) | 0.07 | 0.93 (0.56 - 1.53) |

| Site of isolation of clinical samples | |||||

| Sputum | 40 (29) | 14 (27) | 26 (31) | 0.698 | 0.88 (0.42 - 1.80) |

| Urine | 49 (36) | 15 (29) | 34 (40) | 0.144 | 0.63 (0.35 - 1.12) |

| Wound swab | 4 (2.9) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (2.3) | 0.410 | 1.72 (0.25 - 11.74) |

| Blood | 13 (9.5) | 5 (10) | 8 (9) | 0.585 | 0.88 (0.31 - 2.51) |

| Tracheal aspirate | 8 (9) | 1 (2) | 7 (8) | 0.132 | 0.14 (0.02 - 1.23) |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (1) | > 1.000 | - |

| Catheter | 7 (5.1) | 6 (11.7) | 1 (1) | 0.028 | 5.92 (0.53 - 65.72) |

| Tissues | 4 (3) | 3 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.158 | 2.92 (0.26 - 33.02) |

| Throat | 1 (0.7) | 1 (2) | 0 | > 1.000 | - |

| Synovial fluid | 2 (1.4) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.514 | 1.00 (0.04 - 56.54) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | 4 (3) | 3 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.116 | 3.00 (0.28 - 33.00) |

| Pleural fluid | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.685 | 0.50 (0.04 - 2.76) |

Whereas Table 2 presents, the frequency of isolates obtained from catheters was 4%, which showed a significant difference between the samples acquired from ColS and ColR isolates (10% vs. 1%; P = 0.028). Evaluation of the prevalence of underlying diseases, use of medical devices, duration of hospitalization, and the use of colistin one month before hospitalization displayed no significant difference between the two groups of CRKp (ColR and ColS) isolates (P > 0.05, OD: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.03 - 3.50).

5. Discussion

In this study, we identified four risk factors related to the acquisition of CRKp isolates, including the previous use of aminoglycoside antibiotics, medical devices, long hospitalization, and having an underlying disease. As we and other studies have indicated, the use of carbapenems, long hospitalization, use of medical devices, and underlying disease are considered risk factors for acquiring an infection with CRKp (19). This is probably because people admitted to the hospital for long periods are usually undergoing surgery, taking antibiotics for an extended period, and using a catheter. On the other hand, because these patients are physically weak, they need special care from nurses and staff, and all these are important factors for the spread of resistant bacteria. Therefore, informing the doctor about the high sensitivity of people who are hospitalized for a long time, especially when they have immunocompromised diseases such as diabetes and cancer or use medical devices, can prevent higher mortality after CRKp infection and treatment failure (20). According to another study, the use of fluoroquinolones has a direct relationship with the increased probability of acquiring CRKp because of the mutation or increased spread of carbapenemase genes, which is not the same as in our study (21). In our study, the use of aminoglycosides has a significant association with CRKp isolates, but more detailed molecular studies and the use of a large number of fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside users as a target study population can be helpful.

In gram-negative bacilli, there are various mechanisms involved in microbial resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, the most important of which is the production of beta-lactamase enzymes, particularly ESBLs (22). In the present study, the prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates was 72.3% (n = 275/380). According to a review article, the highest resistance was displayed to be 73% in 2017 (23). In Germany, this rate is 12%, whereas it is 58% in Italy (22, 24). A possible reason for the high frequency of cephalosporin-resistant isolates could be the excessive use of this class of antibiotics. In our research, the most common broad-spectrum beta-lactamase gene was blaCTX-M (68%; n = 168/275), which was in line with other investigations (25, 26).

Carbapenems are often used as the drug of choice in the treatment of severe infections caused by resistant isolates. The emergence and spread of carbapenem-resistant isolates have made treatment more difficult (27). The prevalence of CRKp isolates in Iran has been reported as 11.3% on average (28), but in Italy and the United States, it is 26.9% (29) and 25% (30), respectively. In the current study, the prevalence of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates was 49.4% (n = 136/275), which is most likely due to the inefficacy of beta-lactams and high consumption of carbapenems.

In Enterobacteriaceae, the production of carbapenemases is the main resistance mechanism to carbapenems and mainly includes the enzymes KPC, NDM, IMP, and OXA-48, whose prevalence differs in various countries (30-32). KPC is the most frequent carbapenemase enzyme in North and South America, Europe, Asia (China), and the Middle East (Israel) (33-37). Metallobetalactamase-producing isolates have mostly been reported from countries such as Japan (IMP), Taiwan (IMP), India (NDM), and Greece (VIM) (34, 37, 38). In our study and another conducted in Iran, the carbapenemase genes blaOXA-48 and blaNDM were highly prevalent among K. pneumoniae isolates (39). While we found a high prevalence of resistance to aminoglycosides and quinolones, similar to other surveys, TZP, AN, and colistin indicated favorable activity against CRKp, which can be considered for treating carbapenem-resistant isolates (40). With the increasing prevalence of carbapenem resistance, the use of colistin as the last treatment option has increased in hospitals (41), eventually resulting in the emergence of ColR K. pneumoniae isolates (42). The prevalence rate of colistin resistance varies in different countries (29, 43). Like other studies, the prevalence of colistin resistance was high (37.5%) in our study, which suggests increased usage of colistin (40).

According to another study, the presence of a catheter and resistance to colistin were predictors of mortality, and in our study, catheter use is a risk factor for infection by ColR CRKp. Therefore, in the context of limited antibiotics for treating severe infections, preventing the spread can control mortality. Furthermore, there is no significant correlation between previous exposure to colistin and acquiring ColR CRKp infection. Patients with ColR CRKp without colistin exposure may have received ColR CRKp from another source, such as a person or instrument exposed to colistin, or potentially from food consumption or an indirect diet pathway, which needs verification by molecular epidemiology investigations.

Recently, a plasmid-mediated resistance gene, which plays a key role in the transmission of colistin resistance (mcr), has been reported in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from animals and humans worldwide (42). However, similar to some other investigations (42, 44, 45), we could not find the mcr-1 gene, which was first reported in Iran in 2019 at a rate of 21.8% (29). It is suggested for future studies to investigate other mcr variants and the varied mechanisms of resistance to colistin (44). Studies have also highlighted that NDM-producing isolates of the metallo-betalactamase family have higher lethality (46). Based on the findings of this study, the prevalence of the blaNDM gene was significantly higher in ColR CRKp compared to ColS CRKp, which imposes a serious challenge to the treatment of these isolates.

5.1. Conclusions

The high prevalence of colistin and carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae demands special attention to the existing therapies in the country. The emergence and dissemination of colistin resistance in MDR isolates should be considered by physicians in hospitals to prevent the further spread of resistant isolates by limiting the prescription of last-line antibiotics. Moreover, infection control committees should inhibit the transmission of resistant isolates and subsequent mortality by applying preventive strategies such as protected contacts, staff training, and using separate rooms, particularly for those at higher risk, i.e., the elderly and people with catheters.

5.2. Study Limitations

Limited funds have prevented the collection of more CRKP isolates from all hospitals in the Tehran province. It was also not possible to use more advanced molecular typing technologies, such as multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), to investigate the molecular epidemiology of ColRKp in this study.

5.3. Suggestions

Further studies are needed to identify the most common clones of ColRKp in Tehran.