1. Context

The Staphylococcaceae family received approval in 2009 (1, 2), encompassing nine genera (3). Ogston’s original description in 1883 introduced the genus Staphylococcus (4, 5). Later, Rosenbach further classified this genus into Staphylococcus albus and Staphylococcus aureus (4, 6). In 1886, Flügge distinguished Staphylococcus from Micrococcus (4, 7), emphasizing differences in DNA G+C content: 33 - 40 mol% for Staphylococcus species and approximately 70 mol% for Micrococcus species (4). The validation of the Staphylococcus genus was ultimately confirmed in 1980 (8, 9). Staphylococcus is a member of the Domain Bacteria, Kingdom Bacillati, Phylum Bacillota, Class Bacilli, Order Caryophanales, and Family Staphylococcaceae (10). This genus is the most prevalent member of this family (11). Up to the present time, the S. aureus complex comprises S. aureus, S. roterodami, S. argenteus (formerly identified as S. aureus clonal complex 75 or CC75) (12), S. schweitzeri, and S. singaporensis, playing an essential role in infections affecting both humans and animals. The cell wall structure and chemical composition of Staphylococcus species closely resemble those of other Gram-positive bacteria. Peptidoglycan, protein, and teichoic acid constitute the cell wall of this group of bacteria (13). In some species, the peptidoglycan type is Lys-Gly5–6, and teichoic acids consist of glycerol, ribitol, and N-acetylamino sugars (4). Additionally, the notable fatty acids in S. roterodami are anteiso-C15:0, anteiso-C17:0, and iso-C15:0 (14). The current article emphasizes that this review distinctly focuses on the lesser-known and overlooked members of the S. aureus complex, particularly S. argenteus, S. roterodami, S. schweitzeri, and S. singaporensis. Unlike previous review articles that predominantly focused on S. aureus, our article surveyed recent taxonomic updates, virulence factors, and antibiotic resistance profiles specific to these species. Previous studies reported S. argenteus, S. aureus, S. roterodami, and S. singaporensis from human infections (15, 16). Additionally, we emphasize their important roles in clinical infections and food safety, which have not been addressed enough in the literature. By providing a comprehensive review of existing knowledge and emphasizing the clinical manifestation and epidemiological implications of these species, our review aims to fill important and vital gaps and inspire further research in this field.

2. Isolation from Human Clinical Specimens

Staphylococcus species, especially S. aureus, is a frequent source of various infections in hospitals and the community (17). These bacteria can be isolated from various clinical specimens such as a catheter (18) and skin (4, 19-21) [The swab technique is suitable for isolation (22), and the plate should be incubated at 34 - 35°C for 72 to 96 hours]. Additionally, it can be isolated from sepsis and blood culture (21, 23-25), body fluids (4, 24), joints [joint aspirate and/or intraoperative tissue samples are isolated and cultured on selective media] (24, 26), ocular sources (4, 27), sputum (21), ears (19, 21), and urine when there are 100,000 bacterial cells or more per mL in a midstream specimen. However, this criterion varies in different references. The urine specimen is homogenized, and the loop is vertically introduced into the bottle. The specimen is then seeded onto a blood agar (BA) medium and incubated for 18 to 24 hours at a temperature of 35°C (4, 28), as routinely performed in clinical laboratories. Some data are presented in Table 1. Typically, this genus is isolated on sheep BA in the primary culture within 18 - 24 hours (4). Various selective media isolate Staphylococcus from stool specimens and similar samples like nasal and skin specimens. These include Columbia CNA agar (containing blood, colistin, nalidixic acid) (29), lipase-salt-mannitol agar, mannitol salt agar (30, 31), phenylethyl alcohol agar (containing pancreatic digest of casein, papic digest of soybean meal, sodium chloride, agar, defibrinated sheep blood, phenylethyl alcohol, distilled water] (32), and Schleifer-Krämer (SK) agar [this medium has been used for selective isolation of Staphylococcus species and contains tryptone or peptone from casein, beef extract, yeast extract, glycerol, sodium pyruvate, glycine, KSCN, NaH2PO4 H2O, Na2HPO4 2H2O, LiCl, agar, and distilled H2O] (4) and, tellurite glycine agar (containing tryptone, yeast extract, mannitol, K2HP04, lithium chloride, glycine, agar, potassium tellurite) (33). The incubation period for these specimens is at least 48 - 72 hours (4) at 37°C. Additionally, S. argenteus and S. schweitzeri were cultured on tryptone soy agar (TSA) (enzymatic digestions of casein and soybean meal, sodium chloride, and agar) at 37°C (34, 35). Staphylococcus argenteus has been isolated from community-acquired or healthcare-associated settings (36). Schutte et al. reported that S. roterodami could grow on BA, Brucella BA, chocolate BA, MacConkey agar without salt, and Muller-Hinton agar (14).

| Variables | Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus argenteus (MSHR1132T) | Staphylococcus schweitzeri | Staphylococcus singaporensis (SS21T) | Staphylococcus roterodami |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigmentation | + | -1 a | +2 b | - | |

| β-Hemolysis | + | + | + | + | + |

| Arginine Dihydrolase | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acetoin Production | + | ||||

| Alkaline Phosphatase | + | + | + | + | + |

| Catalase | + | + | + | + | + |

| Coagulase | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nitrate Reduction | + | + | + | ||

| Ornithine Decarboxylase | - | - | |||

| L-Pyrrolidonyl Arylamidase | + | + | + | + | |

| Urease | d c/- | - | - | + | - |

| Hydrolysis of Esculin | - | ||||

| Resistance to Novobiocin | - | - | - | - | |

| Resistance to Polymixin B | + | + | + | + | |

| β-Galactosidase | - | - | - | - | |

| β-Glucosidase | + | - | - | ||

| β-Glucuronidase | - | - | - | - | |

| L-Arabinose | - | ||||

| D-Cellobiose | - | ||||

| Maltose | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Mannitol | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Mannose | + | + | + | + | + |

| Raffinose | - | - | - | - | - |

| D-Trehalose | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sucrose | + | + | + | + | + |

| D-Turanose | + | ||||

| D-Xylose | - | - | - | - | - |

| D-Glucose | + | ||||

| D-Fructose | + | ||||

| D-Galactose | + | + | - | + | |

| Lactose | - | - | - | + | + |

| Growth in 6.5 % NaCl | + | + | + | + | |

| Ref. | (4, 35) | (35) | (35, 37) | (38) | (14) |

a Positive for 11 to 89% of strains.

b Creamy white appearance.

c Yellowish-pigmented, nucA gene was positive in all of species.

3. Food Specimens

Two species of this complex have been isolated from food products, including S. aureus (4, 39) and S. argenteus (32, 36, 40-42). Staphylococcal food poisoning and gastroenteritis may result from the consumption of food contaminated with enterotoxins (43). For isolation of these bacteria from food materials, non-selective enrichment of S. aureus, tryptic soy broth (TSB), and TSB containing 20% NaCl, Egg Yolk Tellurite enrichment, Trypticase soy broth with 10% NaCl and 1% sodium pyruvate (4), Baird-Parker agar (basal medium is containing agar, beef extract, glycine, lithium chloride 6H2O, tryptone, yeast extract) (4, 36), salt egg yolk (SEY) agar (41), and SK agar (basal medium containing agar, beef extract, distilled H2O, glycine, glycerol, KSCN, LiCl, NaH2PO4 H2O, Na2HPO4 2H2O, tryptone or peptone from casein, sodium pyruvate, yeast extract) (4) have been recommended. The incubation period is set at 35 - 37°C for 24 - 48 hours.

4. Animal Specimens

Previous studies have reported the isolation of these bacteria from animals such as bats (44), bovine mastitis (45), gorillas (46, 47), pigs (47, 48), chickens (48), and rabbits (20) (S. argenteus). These studies have also reported infections in bats (44, 49, 50), gorillas (50), and monkeys (50, 51) (S. schweitzeri). Olatimehin et al. employed nutrient broth and Mannitol salt agar to isolate the S. aureus complex from fecal samples of Eidolon helvum at 37°C for 48 hours (44). In another study by Schaumburg et al., the S. aureus complex was isolated from animals and humans by culturing on Columbia BA plate, Columbia CAP selective agar (containing aztreonam and colistin) plate and SAID [S. aureus ID] agar plate for 18 - 36 hours at 36°C (51). Indrawattana et al. used sheep blood and Mannitol salt agar to isolate S. argenteus (at 37°C for 24 - 48 hours) (20).

5. Phenotypic Identification

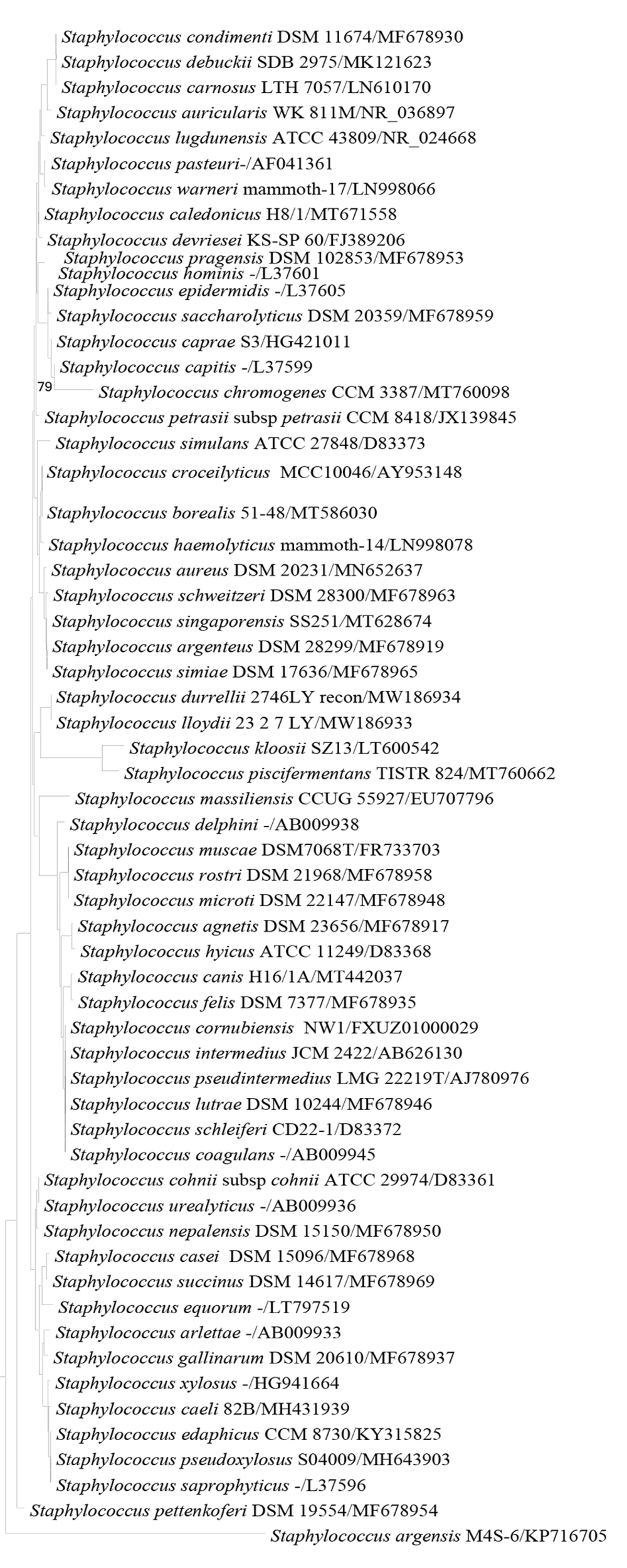

Colonies suspected to be Staphylococcus should undergo gram staining and be identified at both the genus and species levels. Schutte et al. reported that S. aureus and S. roterodami exhibit similar Gram staining characteristics under microscopic examination (14). The color of S. argenteus colonies is silver, as this bacterium lacks the carotenoid pigment staphyloxanthin (52-54). Various phenotypic tests can differentiate staphylococci from other gram-positive cocci with catalase production. These tests include susceptibility to erythromycin and lysostaphin (55), bacitracin (56), furazolidone (57), growth in 6.5% NaCl, coagulase, nitrate reduction, urease, colony morphology, OF (oxidation-fermentation) test, oxidase, hydrolysis of Esculin, acid production from various carbohydrates such as arabinose, cellobiose, maltose, mannitol, mannose, raffinose, trehalose, sucrose, turanose, xylose, glucose, fructose, galactose, lactose, and others (58, 59). Staphylococci are non-motile, non-spore-forming bacteria; some species are facultative anaerobes, and catalase and benzidine tests are positive in these species (4). Staphylococcus roterodami, S. argenteus, S. schweitzeri, and S. singaporensis test positive for coagulase enzymes, similar to S. aureus (14, 35, 38). They exhibit proximity to S. aureus when considering phenotypic and genotypic features (60). According to the phenotypic tests presented in Table 1, phenotypic identification alone is not entirely suitable for the S. aureus complex, and molecular methods are necessary for accurate identification at the species level. 16S rRNA gene sequence of S. simiae is similar to other members of the S. aureus complex (Figure 1), but some phenotypic test results such as coagulase, a-glucosidase, b-glucosidase, hydrolysis of DNA and esculin, and D-mannose were negative. However, acid production from D-maltose, D-mannitol, D-melezitose, D-trehalose, N-Acetylglucosamine, and resistance to polymyxin B were positive (61), indicating differences from these members. Conventional identification is inadequate for distinguishing four species in the S. aureus complex (38). To date, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has also been utilized for identifying the S. aureus complex (14, 20, 25, 35, 37, 44, 49, 62). Tong et al. compromised MALDI-TOF MS identity scores with two databases: A standard clinical database and an amended database with profile proteins from S. aureus, S. argenteus, and S. schweitzeri. In the standard/amended database, identity scores for S. aureus, S. argenteus, and S. schweitzeri were 2.295/2.295, 2.071/2.700, and 1.847/2.676, respectively (35). Indrawattana et al. used two methods, NRPS sequencing and MALDI TOF MS, to identify eight suspicious isolates of S. argenteus. The results of the two methods were reported to be similar (20). Another study by Chen et al. employed MALDI TOF MS for accurate differentiation between S. aureus and S. argenteus. They reported that this method correctly distinguished 100% of the 72 S. argenteus isolates from the 72 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus samples (25).

6. Molecular Identification

16S rRNA gene sequence analysis showed that this genus belongs to the phylum Firmicutes (59). DNA-DNA hybridization (4), 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and their comparative oligonucleotide (63) reveal genetic differences between the two genera Staphylococcus and Micrococcus. Staphylococcus is closely related to genera such as enterococci, Lactobacilli, Listeria, micrococci, and streptococci (4, 59). The DNA G+C content is 30 - 39 mol% in the Staphylococcus genus (4). More than 30 species of the genus Staphylococcus, especially S. aureus, S. argenteus, S. schweitzeri, S. roterodami, and S. singaporensis have been completely sequenced (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/?term = Staphylococcus). Analysis of full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences showed that S. argenteus, S. roterodami, and S. schweitzeri have sequences that are closely related to S. aureus (14, 38). Additionally, these species exhibit differences in nuc gene nucleotides (37). Tong et al. reported the amplification of the nuc gene using conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in S. argenteus, utilizing specific primers provided by Brakstad et al. (5'-GCGATTGATGGTGATACGGTI-3’ forward and 5'-AGCCAAGCCTTGACGAACTAAAGC-3’ reverse (64). They also reported the number of mismatches in the primer sites (35). Eshaghi et al. reported that 22 isolates of S. argenteus tested negative for nuc gene primers specific to S. aureus (37). Hansen et al. reported that the nuc length was 670 bp in all of the isolates of S. argenteus, whereas the nuc length was 687 bp in S. aureus. Additionally, they reported that the S. argenteusnuc gene homology was 83% with the S. aureusnuc gene (19). Another study by Zhang et al. reported that NRPS gene (nrps-F: 5'-TTGARWCGACATTACCAGT-3’/nrps-R: 5'-ATWRCRTACATYTCRTTATC-3’) could simultaneously recognize and differentiate S. argenteus and S. schweitzeri from S. aureus, producing PCR products of ~340 base pairs and ~160 base pairs, respectively (36). Designing primers specific to S. roterodami, S. argenteus, S. schweitzeri, and S. singaporensis will be necessary for accurate and rapid identification. There are various methods for bacterial whole-genome sequencing (WGS), including massively parallel sequencing, Sanger sequencing, and single-molecule sequencing (65, 66). There are various sequencing platforms, including Illumina, MiSeq, MiniSeq, NextSeq, NovaSeq, Ion Torrent, S5, Pyrosequencing, Pacific Biosciences, and Oxford Nanopore sequencing techniques (66-68). To date, WGS is a reliable tool for the taxonomic description of bacterial species, epidemiological studies, and clinical data (69, 70). Based on complete genome sequencing, we can generate a phylogenomic tree and assess the position of species on the evolutionary tree. Also, we can compare two or more species with DNA-DNA hybridization and average nucleotide identity by blast (ANIb) based on the genomic sequences (71). The standard cut-off for ANIb is generally set at 95 - 96% (72, 73). Comparisons based on the whole-genome of S. argenteus (MSHR1132T) and S. schweitzeri (DSM 28300T) to S. aureus demonstrate significant phylogenetic differences, with an average nucleotide identity (ANI) value and DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) of 95% and 70% respectively (35). Average nucleotide identity by blast between S. argenteus MSHR1132 T and S. schweitzeri DSM 28300 T was 92.03%, below the species delineation cut-off. Suzuki et al. conducted a comparative genomic analysis and reported that S. simiae is the sister taxon of S. aureus (74). The ANIb and the percentage of aligned nucleotides [%] for the whole genome sequences of two members of the S. aureus complex are shown in Table 2. The last study reported that multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is a powerful tool for identifying S. argenteus.

| Organism | Staphylococcus argenteus MSHR1132 T | Staphylococcus aureus 502A | Staphylococcus roterodami Zoo-28 | Staphylococcus schweitzeri DSM 28300 T |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. argenteus MSHR1132 [T] | - | 87.62 (84.55) | 93.47 (87.04) | 92.03(86.41) |

| S. aureus 502A | 87.41 (85.98) | - | 87.85 (84.39) | 88.69 (86.05) |

| S. roterodami Zoo-28 | 92.82 (87.55) | 87.81 (81.67) | - | 92.74 (85.00) |

| S. schweitzeri NCTC13712 [T] | 91.82 (87.40) | 88.72 (86.13) | 92.83 (86.83) | - |

a Genome sequence of type strain S. singaporensis was not available in Genebank database.

7. Multilocus Sequence Typing

Multilocus sequence typing is a method that generally involves the amplification of seven housekeeping gene loci using PCR. In the following, PCR products are sequenced, and then these nucleotide sequences are compared to established allelic profiles. A variation in a single nucleotide at any loci showed a distinct allele, contributing to determining the sequence type (ST) (75). Zhang et al. reported three new STs, including ST3261, ST3262, and ST3267 (36). In the literature, for the taxonomy of the genus Staphylococcus, five housekeeping genes, namely gap, hsp60, rpoB, sodA, and tuf, have been used and are suitable for distinguishing S. argenteus from S. aureus (76). Wu et al. utilized the MLST method with several housekeeping genes such as arcC, aroE, glpF, gmk, pta, tpi, and yqil to identify S. argenteus. In their study, eight different STs were identified in the 114 isolates, and they reported five new types, including ST5054, ST5055, ST5056, ST5057, and ST5058. ST2250 was the most common ST, and the prevalence of ST1223, ST2854, ST5057, ST5054, ST5056, ST5058, ST5055 were 14.0%, 2.6%, 2.6%,1.8%,1.8%,1.8%,0.9% respectively. They reported two clonal complexes, including CC2250 and CC1223 (42). Indrawattana et al. reported STs in the Staphylococcus complex, including ST4209, ST4210, ST4211, ST4212, and ST4213 (20). Hsu et al. performed MLST on 96 isolates of S. argenteus, and they reported four STs: ST1223 (10.4%), ST2198 (2.1%), ST2250 (75%), and ST2793 (12.5%). In their study, all ST2250 isolates harbored CRISPR loci, while other types did not carry CRISPR loci. They also employed pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and Spa typing for genetic associations. Other genes, including Coa, DnaJ (hsp40), GroEL (hsp60), spacer sequencing, and accessory gene regulator (agr) group have been sequenced and analyzed (62). The phylogenetic tree of the Staphylococcus species was constructed using the molecular evolutionary genetics analysis program version 5 (MEGA5) (Figure 1).

8. Clinical Diseases, Virulence Factors, Antibiotic Resistance, and Epidemiology

Staphylococcus argenteus infections caused by S. argenteus are associated with various clinical manifestations, with a higher prevalence in skin and soft tissue infections. Compared to S. aureus, this bacterium is more sensitive to oxidative stress and susceptible to neutrophil killing due to the lack of pigment staphyloxanthin and fewer virulence factors (4, 77, 78). Human infections with S. argenteus are linked to a milder course of the disease (12, 79). Compared with S. aureus, S. argenteus infections cause less respiratory failure during hospitalization, with a non-significant similar trend for shock and no difference in mortality within 28 days. S. argenteus is also more susceptible to antimicrobial drugs (24). Although it can induce blood infection (24, 79, 80), bacteremia associated with S. argenteus poses a higher risk of mortality than methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) associated with bacteremia (81). Additionally, it may lead to nosocomial infections and invasive diseases (25, 79). Staphylococcus argenteus has been isolated from the blood culture of a woman with necrotizing fasciitis infection in Australia (52). This bacterium (22WJ8192) was isolated from a blood sample taken from the peripheral vein of a seven-month-old female infant in Eastern China (29). On the other hand, S. argenteus infection is more likely to lead to kidney disease and diabetes in adults than MSSA (79). It causes various infections such as mycotic aortic aneurysm (82), bone and prosthetic joint infection (83-85), purulent lymphadenitis (86), foreign-body infections (87), atopic dermatitis lesions (88), and keratoconjunctivitis (89). Although this group of bacteria may be pathogenic in food and milk, it may also trigger bovine mastitis (90). Small colony variants (SCVs) of S. argenteus strain pose challenges to therapeutic strategies, especially when amikacin is used or in chronic infections (91). Staphylococcus argenteus carries several toxin genes, such as Panton-Valentine leukocidin (20, 41, 47, 77, 80, 92-94). However, some findings have indicated a lower prevalence of virulence genes than S. aureus (77, 93). Other findings suggest the absence of the pvl virulence gene in it (24, 95-98).

Recently, whole genome sequencing (WGS) revealed that the nucleotide sequence similarity in the pvl gene between S. argenteus and S. aureus is 75%, and this gene is more prevalent among S. argenteus isolates (94). Staphylococcus argenteus contains the esxB to induce pathogenesis of abscess; the ear gene is proposed for penicillin-binding protein and, ebh, esaB, seh, chp, lip, seg, esaC, esxB, sei, selu2, selm, and selo as adherence genes (19). Furthermore, other virulence factors such as atlE (autolysin), ebp (elastin binding protein), (37), icaA, icaB, icaC, and icaR, clfA, clfB, fnbA, fnbB, fib, and cna (intercellular adhesion) (37, 42, 84), sak (staphylokinase) (19, 21, 37, 47, 85, 99-101), scn (staphylococcal complement inhibitor) (19, 37, 47, 85, 101), spa (staphylococcal protein A) (37, 38), sspB (cysteine protease), hysA (hyaluronate lyase) (37), geh and lip (lipase) (19, 37), coa (staphylocoagulase) (37, 38, 99), nuc (thermonuclease) (37), cap5 and cap8 (capsular) (19, 37), hla (alpha hemolysin) (20, 37, 41, 77, 93, 94, 99), hld (delta hemolysin) (37), eta (exfoliative toxin type A) (37, 99) and hlgA, hlgB, and hlgC (gamma hemolysin) (37, 99), tst (toxic shock syndrome toxin) (19-21, 23, 37, 41, 47, 77, 92-94, 99, 101, 102), esaC, esxB, esxA, esaG, essA, essB, essC, adsA, and essA (type VII secretion system) (19, 47), mazE, Yef M [antitoxin component of type-II toxin-antitoxin (TA) system] (47), can (collagen binding protein), bap, and eno (biofilm production genes) (42), bbp (sialoprotein-binding protein gene) (62) have been reported in this group of bacteria. It forms silver colonies due to the lack of production of the carotenoid pigment staphyloxanthine, encoded by the operon crtOPQMN. Carotenoid pigment expression is associated with decreased bacterial virulence and density in the cardiac valve, spleen, and kidneys (53). The rate of antibiotic resistance appears to be lower in the members of the genus of S. aureus complex than in S. aureus (24). Staphylococcus argenteus strains seem to acquire more antibiotic resistance genes (Table 3) than other species (S. schweitzeri, S. singaporensis, and S. roterodami), especially in clinical isolates, and it is an issue of concern (103). While the isolates of penicillin-resistant (with or without blaZ) strains are common (20, 21, 23, 99-101), other antibacterial resistance are scarce, such as tetracycline (with or without tet genes), gentamycin, clindamycin, erythromycin, fusidic acid, ampicillin, and daptomycin (18, 41, 42, 99, 100, 104). Regarding the prevalence of methicillin resistance isolates (cefoxitin or oxacillin with or without mecA genes), findings vary across the globe (19, 37, 101, 103, 104). Nevertheless, the presence of SCCmec type IV is rarely indicated (19, 94, 101). In numerous epidemiological studies, S. argenteus is associated with various human and animal specimens. It has been reported from Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand (4 studies), Japan (6 studies), Myanmar, Taiwan, China (2 reports each), and Singapore (1 study). Relatively few studies have been reported from African and European countries, including Sweden (2 studies), Gabon, Nigeria, Denmark, France, Belgium (each country with one report), and England (2 studies), However, recent efforts have shown an increased focus on these regions (Table 4).

| Bacterium | Common Resistant Antibiotics | Common Susceptible Antibiotics | Resistance Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus argenteus | Penicillin (with/without blaZ), tetracycline (with/without tet genes), gentamicin, clindamycin, erythromycin, fusidic acid, ampicillin, daptomycin | More susceptible than S. aureus; lower antibiotic resistance overall | mecA (variable prevalence), SCCmec type IV (rare), blaZ, tet genes |

| S. schweitzeri | No reported resistance | Susceptible to all tested antibiotics | No known resistance genes |

| S. singaporensis | One isolate resistant to gentamicin | Susceptible to penicillin, mupirocin, oxacillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, fusidic acid, ciprofloxacin, minocycline, linezolid, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, teicoplanin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, vancomycin | No known resistance genes |

| S. roterodami | Resistant to polymyxin B | Susceptible to cefoxitin, benzylpenicillin, oxacillin, gentamicin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, linezolid, teicoplanin, vancomycin, tetracycline, fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin, fusidic acid, mupirocin, rifampicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | No known resistance genes |

| Country | Year | Type of Study | Sample Type | Total Sample | Values | Identification Method | Bacteria Species | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-based/ Conventional PCR Methods | Band-based Methods | MALDI-TOF | ||||||||

| Thailand | 2016 | Prospective cohort observational study | Sepsis (abscesses n = 163, blood n = 115, bone or arthocentesis n = 21, body fluids, biliary tract and cerbrospinal fluid n = 7, pus from implanted surgical hardware n = 3, pus from spaces such as sinuses and inner ear n = 2) | 311 | 58 (19) | MLST | PFGE | S. argenteus | (24) | |

| Japan | 2017 | Case study | Fecal specimens, food, table, workbench, and empty lunch boxes | 10 | 10 | WGS, MLST | S. argenteus | (40) | ||

| Japan | 2018 | 2 case study | Fecal specimens, food samples, and swabs of cooking utensils | 51 | 36 | MLST | PFGE | S. argenteus | (40) | |

| Gabon | 2016 | Research article | Faucal specimens of wild-living apes (gorilla) | 1 | - | MLST | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (46) | |

| Japan | 2020 | Retrospective observational cohort study | Blood culture | 21 | 2 (1) | MLST | S. argenteus | (23) | ||

| Thailand | 2015 | Cohort | Invasive infection (Blood culture) | 246 | 10 (4.1) | MLST | S. argenteus | (18) | ||

| Myanmar | 2017 | Nasal swab (food handlers) | 563 | 5 (4.5) (in 110 carrier) | MLST | S. argenteus | (105) | |||

| Taiwan | 2018 | Retrospective study | Blood culture | 915 | 97 | MLST | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (25) | |

| Thailand | 2019 | Original article | Pus (rabbits) | 67 (19 bacteria isolates) | 3 | MLST | MALDI‐TOF MS. | S. argenteus | (20) | |

| Gabon | 2021 | An in vitro study | Monkeys (n = 38), bats (n = 16), humans (n = 3) and gorilla (n = 1) | 156 | 58 | MLST, WGS | S. schweitzeri | (50) | ||

| Nigeria | 2020 | Fomites samples (currency note, computer keyboard) | 239 | 2 | MLST, Wholegenome sequencing | MALDI-TOF MS | S. schweitzeri | (106) | ||

| Nigeria | 2018 | Original article | Fecal samples from E. helvum | 250 samples (53 isolates) | 11 (14) | MLST | MALDI-TOF MS | S. schweitzeri, S. argenteus | (44) | |

| Gabon | 2017 | Short communication | Pharyngeal swabs (Bat) | 133 | 2 (4) | PCR, MLST | MALDI-TOF MS | S. schweitzeri | (49) | |

| Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Congo | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | Anterior nares and the pharyngeal mucosa (human and monkey) | Human (1288) and animal (698) | 24 | PCR, MLST | S. schweitzeri | (51) | ||

| United Kingdom | 2021 | Molecular epidemiology case-study | Nasal and throat swab RM recruits) | 1012 | 6 (4 recruits) | WGS, MLST | S. argenteus | (99) | ||

| Japan | 2019 | Clinical specimens: Sputum (6), pharyn× (2), nasal discharge (2), stool (4), skin and abscess (3), urine (2), vaginal discharge (2), ear discharge (1), blood ( 1), and subdural abscess (1) | 23 patients | 24 | PCR, MLST | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (21) | ||

| Thailand | 2017 | Invasive infection | 68 | WGS, MLST, PCR | S. argenteus | (100) | ||||

| Denmark | 2017 | Skin and soft tissue infection, wounds, the ear, the nose | 25 | WGS, MLS, PCR | S. argenteus | (19) | ||||

| Sweden | 2019 | Throat swab, perineum, wound, abces, eczema | 16 | WGS | PFGE | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (104) | ||

| Belgium | 2016 | Retrospectively study | Clinical laboratories, nasal samples | 1650 | 3 (0.16) | MLST and SCCmec typing | S. argenteus | (101) | ||

| China | 2016 | Short communication | Food products, healthy humans, or hospital infections | 839 | 6 | MLST | S. argenteus | (36) | ||

| United Kingdom | 2021 | Original article | Human, Pig, Gorilla | 132 | MLST, CRISPRCasFinder web-server | S. argenteus | (47) | |||

| France | 2020 | Case study | Prosthetic-joint infection | 1 | WGS | S. argenteus | (84) | |||

| Sweden | 2020 | Short Research Communication | Prosthetic-joint infection | 1 | WGS | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (87) | ||

| North American | 2021 | Original article | Clinical samples (sterile sites, 11 from nonsterile sites, and 4 from surveillance screens) | 22 | WGS, 16S rRNA gene analysis | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (37) | ||

| Singapore | 2021 | Retrospective cohort study | Clinical and screening samples | 43 | 37 | WGS, MLST | S. argenteus, | (38) | ||

| Singapore | 2021 | Retrospective cohort study | Clinical and screening samples | 43 | 6 | WGS, MLST | S. singaporensis sp. | (38) | ||

| Indonesia | 2021 | Foot wound | 1 | 16S phylogeny, MLST | MALDI-TOF MS | S. roterodami sp. | (14) | |||

| Gabon | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | Human throat swabs, skin lesions | 103 | 3 (2 from school children) | MLST | S. schweitzeri | (107) | ||

| China | 2020 | Retail foods (4300 samples) | 1581 | 114 | MLST | S. argenteus | (42) | |||

| United States | 2020 | Case report | Hemodialysis catheter | 1 | MALDITOF MS | S. argenteus | (18) | |||

| Taiwan | 2020 | Blood | 96 | MLST | PFGE | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (26) | ||

| Myanmar | 2019 | Research article | Nasal isolates of healthy food handlers (563), clinical isolates (wound swab, pus, and blood) | 144 + 137 | 6 | MLST | S. argenteus | (108) | ||

| Japan | 2020 | Case report | Conjunctival scraping | 1 | Whole-genome sequence, MLST | MALDITOF MS | S. argenteus | (89) | ||

| Japan | 2021 | Clinical specimens | 82 | 3 (0.66) | MALDI-TOF MS | S. argenteus | (103) | |||

Abbreviations: RM, royal marines; WGS, whole-genome sequencing; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; MLST, multilocus sequence typing.

Staphylococcus schweitzeri: S. schweitzeri is typically acquired as a strain that colonizes the nasopharynx of Afrotropical wildlife, particularly in primates and bats. However, it can also be found on fomites (50, 51, 106), and three S. schweitzeri isolates have been reported from human nasopharyngeal samples in Gabon (107). It has exhibited nearly the same virulence factor as those presented in other S. aureus complexes, such as exfoliative toxins, toxic shock syndrome toxin (tst) enterotoxins (seb, sec), Panton-Valentine leukocidins (50, 51), autolysins, hemolysins (hla) (49, 50), adhesins, polysaccharide capsules, immune evasion factors, and fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPA, FnBPB) (50, 51). It can exert a cytotoxic effect on the human cell line (77) and has demonstrated host cell invasion, activation of host cells with the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and intracellular cytotoxicity comparable to S. aureus. However, its extracellular cytotoxicity surpasses that of S. aureus. Moreover, it can produce more biofilm than S. aureus but is lower than Staphylococcus epidermidis. It is also capable of escaping from phagolysosomes (50). However, fecal specimens from straw-colored fruit bats (Eidolon helvum) (44) and fomites S. schweitzeri isolates revealed the absence of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes. Only one of the isolates contains icaC (intracellular adhesion gene) (106). Seems likely S. schweitzeri will emerge as a zoonotic strain within the genus Staphylococcus. As of now, no antibiotic resistance has been reported (107). In terms of epidemiology, S. schweitzeri appears to be associated with wildlife. It has been reported in several countries, including Gabon (2 reports), Nigeria (2 reports), Côte d’Ivoire, and Congo (1 report).

9. Staphylococcus singaporensis and Staphylococcus roterodami

The clinical manifestations of S. singaporensis isolated from cholecystostomy were similar to those caused by S. aureus. It led to skin and soft tissue infections in 66.7% of cases. However, S. singaporensis appears to possess fewer toxin genes than S. aureus. This bacterial group contains staphylococcal protein A, coagulase, and crtM genes, but it lacks staphylococcal enterotoxins, tst-1, pvl, and mobile genetic elements such as phages, pathogenicity islands, and genomic islands (38). Staphylococcus roterodami has been isolated from a foot wound specimen in the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam. However, this bacterium’s pathogenicity and virulence factors have not been investigated (14). Overall, S. singaporensis isolates are susceptible to various antibiotics, including penicillin, mupirocin, oxacillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, fusidic acid, ciprofloxacin, minocycline, linezolid, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole, teicoplanin, quinupristin – dalfopristin, and vancomycin while one isolate shows resistance to gentamicin (38). On the other hand, S. roterodami is susceptible to all antimicrobial drugs, including cefoxitin, benzylpenicillin, oxacillin, gentamycin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, linezolid, teicoplanin, vancomycin, tetracycline, fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin, fusidic acid, mupirocin, rifampicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, except for polymyxin B (14). S. singaporensis and S. roterodami differ in their epidemiology; S. singaporensis has been reported from Singapore, while S. roterodami has been indicated from Indonesia. As of this writing, no further reports of these bacteria have been published, and no data on resistance genes, virulence factors, and the epidemiology of these bacteria are available.

10. Role of Staphylococcus aureus Complex in Food Poisoning

Staphylococcal food poisoning (SFP) is caused by staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs), which are formed beforehand in food products. Various species of Staphylococci, including S. aureus and recently S. argenteus, carry SE genes found in mobile genetic elements (41, 109). Different studies have proposed twenty SE and SE-like genes, including five classical enterotoxins (sea-to-see genes) (110, 111). Various new SEs (SEG, SEH, SEI, SEM, SEN, and SEO) have recently been identified as triggers for SFP without producing SEs (112, 113). As mentioned, S. argenteus is also one of the leading causes of foodborne diseases globally, with various staphylococcal enterotoxin genes (sea, sec, sed, seb, seg, sei, sem, sen, seo, selu2, sec3, ear, selk, selq, selX, secY, sey, sea, sed) reported from food specimens (19-21, 23, 41), (37, 47, 77, 92-94), (99, 101, 102).

11. Conclusions

The present review focuses on the unique clinical, taxonomic, and antimicrobial resistance profiles of the S. aureus complex, specifically S. argenteus, S. schweitzeri, S. roterodami, and S. singaporensis. Although S. argenteus and S. aureus share similarities, S. argenteus has a lower virulence but a higher bacteremia-related mortality. S. schweitzeri is mainly linked to wildlife and has the potential to be transmitted to humans, while S. singaporensis and S. roterodami remain poorly understood. Significant knowledge gaps in global epidemiology, resistance mechanisms, and transmission patterns need further genomic and clinical research. Accurate diagnosis, infection control, and food safety monitoring are crucial to minimize these emerging pathogens’ risks.