1. Background

Macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin B (MLSB) antibiotics are structurally different with a same mechanism of action. These drugs, especially clindamycin, are alternative drugs for some Staphylococcus aureus infections such as skin and soft tissue infections particularly in penicillin-allergic patients (1, 2). Clindamycin resistance in S. aureus strains may be either constitutive (cMLSB) or inducible (iMLSB). Inducible resistance to clindamycin was first recognized in the early 1960s. Relapse of infection in a patient with S. aureus endocarditis was reported in 1976 (3). Detection of isolates with inducible clindamycin resistance is a problematic issue for the routine diagnosis, because they are erythromycin resistant and clindamycin susceptible in vitro and in the condition that they are not place adjacent to each other. In these cases, in vivo treatment with clindamycin may lead to clinical therapeutic failures (4, 5).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence of inducible clindamycin resistance in S. aureus isolates collected from clinical specimens in this geographic area.

3. Materials and Methods

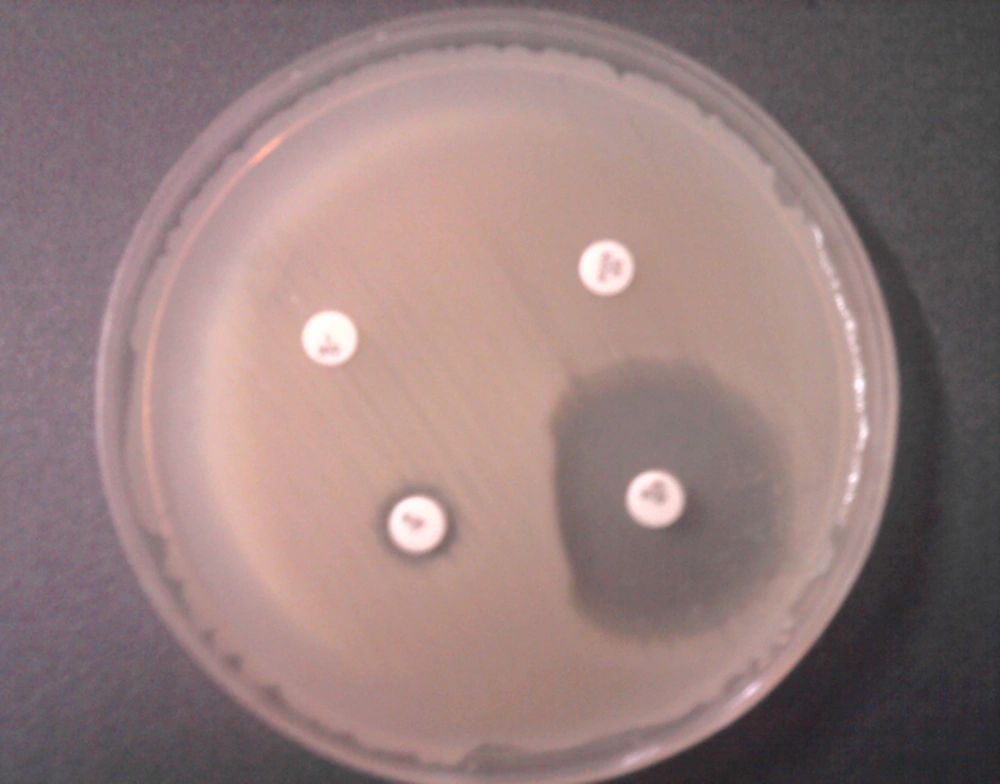

Totally 162 S. aureus isolates were collected from clinical specimens of patients admitted to three university hospitals with 462, 420 and 300 bed capacities in Kerman, south-east of Iran, from March 2011 to February 2012. Confirmation of S. aureus isolates and detection of methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) were performed by phenotypic and genotypic methods as previously described (6). Only one isolate per patient was included in the study. ‘D-test’ was used for detection of inducible resistance to clindamycin. This test was performed by placing an erythromycin (15 µg) disk (Mast, Group Ltd., Merseyside, UK) at a distance of 15 to 20 mm from clindamycin (2 µg) disk (Mast, Group Ltd., Merseyside, UK) on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate inoculated with 0.5 McFarland standard bacterial suspensions. Following overnight incubation at 37°C, flattening of the clindamycin zone adjacent to the erythromycin disk (D shaped) indicated inducible clindamycin resistance (7). S. aureus ATCC 25923 was used as the control strain.

4. Results

From 162 S. aureus isolates tested for determination of inducible clindamycin resistance, 70 (43.2%) were MSSA and 92 (56.8%) isolates were MRSA (Table 1). Susceptibility to erythromycin and clindamycin of these isolates is presented in Table 1. Sensitivity to both erythromycin and clindamycin was significantly higher in MRSA compared to MSSA isolates. Resistance to methicillin, erythromycin and clindamycin was observed in 92 (56.8%), 75 (46.29%) and 46 (28.4%) of the isolates, respectively. Inducible resistance to clindamycin was determined in 14 (8.64%) isolates (D-test positive, Figure 1). Table 2 shows the distribution of D-test positive S. aureus isolates in clinical specimens. Among those, 11 (78.57%) were MRSA and 3 (22.43%) were MSSA (Table 2).

| Susceptibility Pattern (Phenotype) | MSSA | MRSA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erys Clis | 57 (81.43) | 26 (28.26) | 83 (51.23) |

| Eryr Clir (cMLSB) | 2 (2.85) | 44 (47.82) | 46 (28.39) |

| Eryr Clis (D test positive, iMLSB) | 3 (4.28) | 11(11.95) | 14 (8.64) |

| Eryr Clis (D test negative) | 5 (7.14) | 10 (10.87) | 15 (9.26) |

| Erys Clir | 2 (2.85) | 1 (1.08) | 3 (1.85) |

| Total | 70 (43.2) | 92 (56.8) | 162 (100) |

aAbbreviations: MSSA, Methicillin susceptible S. aureus; MRSA, Methicillin resistant S. aureus; Ery, Erythromycin; Cli, Clindamycin; s, Sensitive, r, Resistant; cMLSB, Constitutive macrolide lincosamide and streptogramin B; iMLSB, Inducible macrolide lincosamide and streptogramin B.

bData are presented as No. (%).

| Isolated Area | D-Test Positive | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MSSA | MRSA | Total | |

| Urine, (n = 45) | 1 (2.22) | 6 (13.33) | 7 (15.55) |

| Wound, (n = 38) | 1 (2.63) | 5 (13.15) | 6 (15.78) |

| Bronco alveolar lavage, (n = 14) | 1 (7.14) | 0 | 1 (7.14) |

| Other samplesc, (n = 65) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total, (n = 162) | 3(1.85) | 11(6.8) | 14 (8.64) |

aMSSA, Methicillin susceptible S. aureus; MRSA, Methicillin resistant S. aureus.

bData are presented as No. (%).

cIncluding: blood, skin and soft tissue, cerebrospinal fluid.

5. Discussion

Clindamycin is an effective antibiotic agent used in the treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections caused by S. aureus isolates. This antibiotic has good tissue penetration, potential antitoxin effects, and also accumulates in abscesses (8). However, resistance to clindamycin may develop in S. aureus isolates with inducible phenotype and these isolates have a high rate of spontaneous mutation which would enable these isolates to develop constitutive resistance to clindamycin during therapeutic process (4).

A positive D-test indicates the existence of inducible resistance to clindamycin. In this study 8.64% of 162 S. aureus isolates were D-test positive that is comparable with the findings of the studies by Rahbar and Hajia (9.7%) (9) and Sedighi et al. (6.3%) (10) From Iran and Azap et al. (5.7%) from Turkey (11). The prevalence of inducible and constitutive clindamycin resistance differs in different geographic areas (12).

In our study high number (46.29%) of S. aureus isolates were resistant to erythromycin. Among those, 14 (18.66%) isolates had positive and 15 (20%) had negative D-test results and 46 (61.33%) were constitutive clindamycin resistance. In this study the prevalence of inducible and constitutive resistance to clindamycin in MRSA (11.95% and 47.8% respectively) is higher than those in MSSA (4.28% and 2.85%, respectively). Our results were in accordance to the results of Seifi et al. (13) from Iran. The results of this study revealed that inducible resistance to clindamycin in S. aureus isolates is relatively high in this region. Since isolates with inducible resistance may mutate and change to constitutive resistance. Therefore, D-test should be performed to prevent treatment failures of S. aureus infections caused by the agents that are resistant to erythromycin and sensitive to clindamycin.