1. Background

Blastocystis is a zoonotic protozoan parasite living in the digestive system of some vertebrates (1). For the first time in 1911, it was found as a fungal yeast in human stool specimen; then, it was identified as a nonpathogenic protozoan and was forgotten for decades (2, 3). Between 1970 and 1980 with several studies conducted on Blastocystis, the first spark of attraction was paid in relation to biology and clinical features of this parasite (4). In recent decades, identification of this parasite has had a significant progress (3). The results of epidemiological studies, in vitro studies, and research on laboratory animals has shown that this parasite is potentially pathogenic (3).

Several factors such as parasite load, secreting enzymes such as cysteine protease, parasite subtypes, parasite proteins and even host conditions are involved in the pathogenesis of parasite (5-8). Blastocystis has a worldwide distribution and is transmitted by cysts via contaminated food and water (9, 10). Its prevalence in developing countries is more than in developed countries, which is a result of poor health (11). Isolates of the parasite separated from human are called Blastocystishominis and those from animals are generally called Blastocystis sp. In addition, some classifications may be based on the relevant hosts (12). To recognize the genotypes of Blastocystis sp., a PCR was performed using seven pairs of sequence-tagged sites (STS) primers (13).

Each subtype has a specific tendency to specific hosts. For example, human is the main host of ST3, pig and cattle are the main hosts of ST5, and rodents are the main hosts of ST4; but these hosts are not specific for Blastocystis and the parasite has been reported in human too, which is the sign of zoonotic Blastocystis (3). Blastocystis is mysterious and unique with several morphologies and sizes. Its microscopic diagnosis is difficult so that it is sometimes even ignored by experienced people. Various methods such as direct wet-mount, Lugol's iodine staining, formaldehyde-ether sedimentation, dedicated staining, culture and PCR have been used for its diagnosis; PCR is the most sensitive method with high specificity (14, 15).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the subtype of Blastocystis in infected cattle in Khorramabad city, Iran, using seven pairs of STS primers. It was performed for the first time in Iran as an introduction to future studies of subtype prevalence in other animals, also assessing the effect of subtypes on pathogenicity of parasites in animals, particularly in cattle.

3. Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was performed on 196 isolates from cattle stool samples collected from slaughterhouse in Khorramabad city, Iran, in 2012. The samples were collected in disposable containers with no fixative. To eliminate waste, 2 g of stool was added to 10 mL of normal saline solution and the mixture was passed through an 80-micron filter. Afterwards, it was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 200 rpm and 200 mg of the sediment was added to a 1.5 mL microtube (16). DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA stool mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The samples were stored at -20ºC for later use.

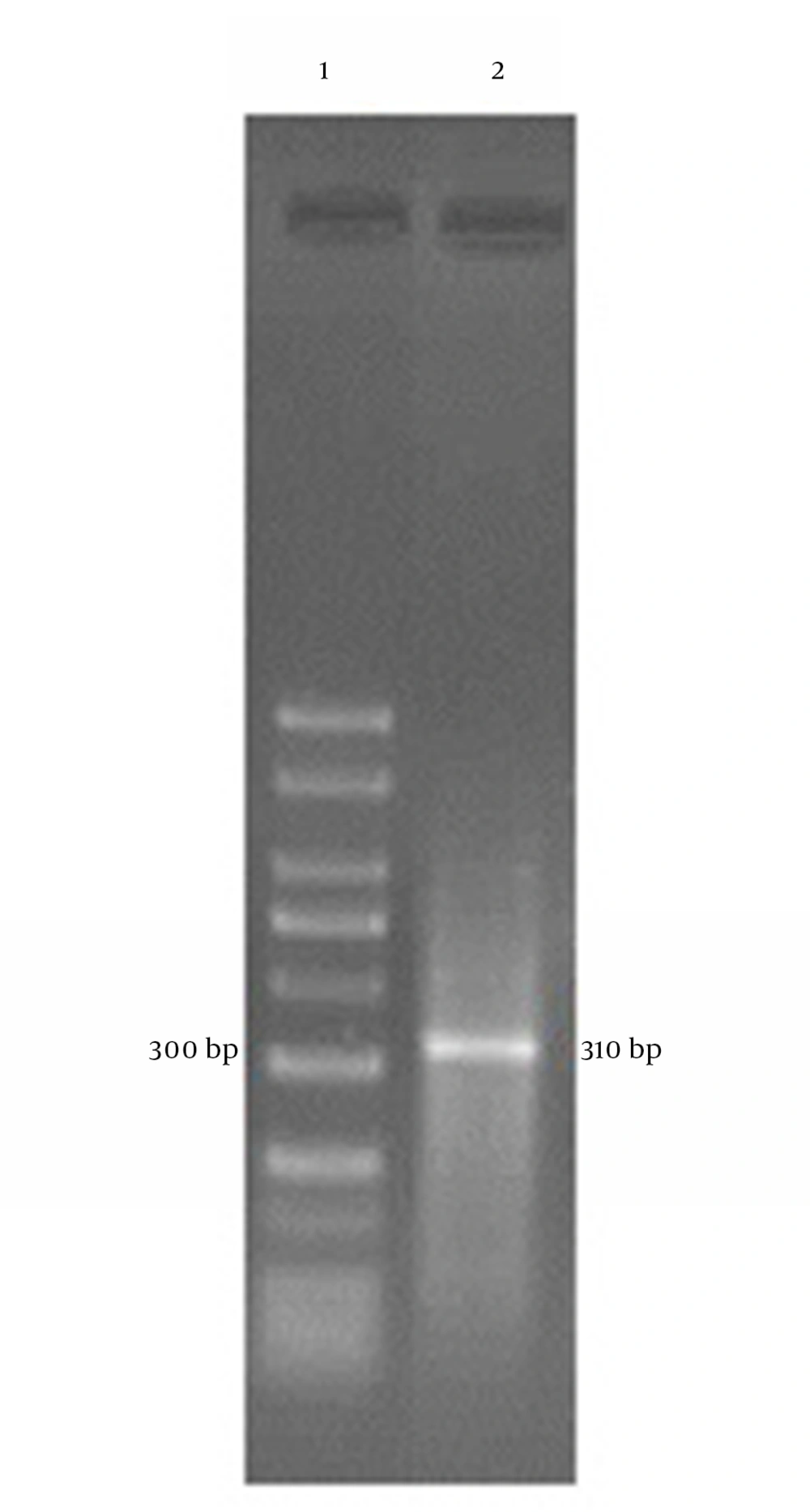

First, primary primers were used according to previous studies for Blastocystis identification (14), b11400 FORC (5`-GGA ATC CTC TTA GAG GGA CAC TAT ACA T-3`) and b11710 REVC (5`-TTA CTA AAA TCC AAA GTG TTC ATC GGA C-3). The PCR was performed in a thermocycler (Corbett, Australia) with the following conditions: one initial denaturing cycle at 94ºC for five minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 94ºC for one minute, 58ºC for one minute, and 72ºC for one minute, and finally one cycle of 72ºC for five minutes (14). At the end, the PCR products were analyzed using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. The expected PCR product was 310 bp.

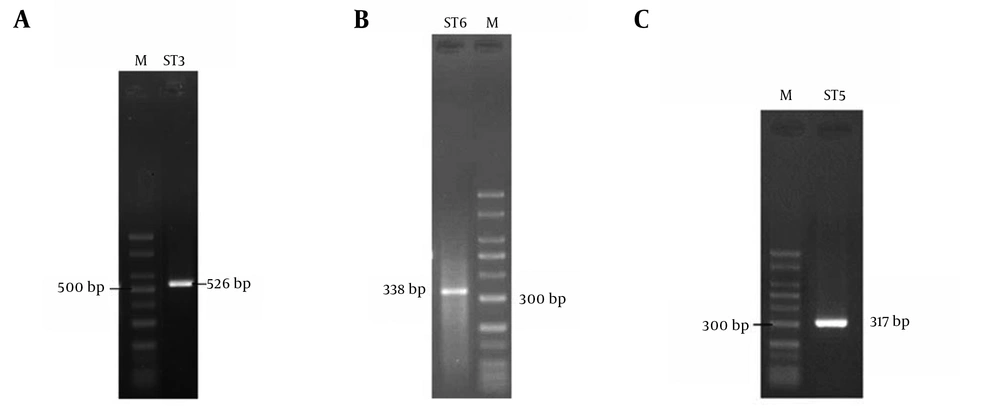

To determine the subtype of Blastocystis in positive samples, seven pairs of STS primers were used as shown in Table 1 (13, 17). The PCR program was conducted with an initial denaturation at 94ºC for five minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 94ºC for 40 seconds, 57ºC for 40 seconds, 72ºC for 40 seconds, with a final extension at 72ºC for five minutes (13, 17). The expected PCR products for each subtype are shown in Table 1. The DNA was prepared by PCR, using seven pairs of STS primers and was sent to Bioneer Corporation, Korea, for sequencing.

| Primer Subtype | Primer Name | Product Size, bp | Gen Bank Acc. No. | Sequences of F and R Primers (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST I | SB83 | 351 | AF166086 | F: GAAGGACTCTCTGACGATGA/R: GTCCAAATGAAAGGCAGC |

| ST II | SB340 | 704 | AY048752 | F:TGTTCTTGTGTCTTCTCAGCTC/R: TTCTTTCACACTCCCGTCAT |

| ST III | SB227 | 526 | AF166088 | F:TAGGATTTGGTGTTTGGAGA/R: TTAGAAGTGAAGGAGATGGAAG |

| ST IV | SB337 | 487 | AY048750 | F:GTCTTTCCCTGTCTATTCTTGCA/R: AATTCGGTCTGCTTCTTCTG |

| ST V | SB336 | 317 | AY048751 | F:GTGGGTAGAGGAAGGAAAACA/R: AGAACAAGTCGATGAAGTGAGAT |

| ST VI | SB332 | 338 | AF166091 | F:GCATCCAGACTACTATCAACATT/R: CCATTTTCAGACAACCACTTA |

| ST VII | SB155 | 650 | AF166087 | F:ATCAGCCTACAATCTCCTC/R: ATCGCCACTTCTCCAAT |

Primer Sequences Used in the Study a

4. Results

Of 198 specimens, 19 (9.6%) were infected with Blastocystis (Figure 1). Three subtypes including ST3, ST5 and ST6 were found by PCR analysis of the positive samples using the STS primers (Figure 2). Among the 19 positive samples, the most common subtype was ST5 (47.36%), followed by ST3 (10.53%) and ST6 (10.53%) (Figure 2). Two (10.53%) samples had mixed infections by ST3 and ST5. The four isolates not amplified by any STS primer were probably unknown genotypes. ST1, ST2, ST4, and ST7 were not identified in the samples under study. The obtained sequences were compared to the sequences reported in Gene Bank and the results showed high homology with Blastocyctis sp. Nucleotides sequence data with accession numbers CJX524459, CJX483863, and CJX524460 respectively for ST3, ST5 and ST6 have been submitted to the GenBank database.

5. Discussion

More studies on this parasite have been performed within the recent 10 years and many indices such as morphology, mode of transmission, parasite dissemination, reservoir hosts, and medical importance have been found, while unknown issues like pathogenicity have remained. Studies have been performed on pig and dog in Iran to evaluate gastrointestinal parasites such as Blastocystis by the microscopy method (18, 19). This study was the first to investigate the Blastocystis subtype in cattle using molecular methods in Iran. In the present study, the highest prevalence was for ST5 which is so important for epidemiology and risk of human infection. As has been reported in similar studies, there is a higher risk of ST5 existence in animals and humans who live close to them (20-22).

The main hosts of ST5 are pig and cattle; most of the studies have been conducted on pig for its use in food worldwide (23). In Iran, due to Islamic issues, pork is not consumed and instead, beef is commonly used. Therefore, people's contact with cattle is more common than pig. In some studies, it has been reported that being in contact with animals has provided the transmission of animal subtypes to human (24). The reports of high prevalence of ST5 in studies on humans in Iran can confirm that this subtype is zoonotic (20-22, 25). However, some researchers believe that ST5 is not zoonotic and is found only in pig and cattle (23, 26).

On the other hand, ST3 reports in cattle as a subtype in human shows the risk of infection transfer between human and cattle. Since many of the cattle in this study grazed on farms contaminated with human stool, the zoonotic nature of Blastocystis was reconfirmed. Another important point in this study was the ST6 report. In studies conducted in other countries, ST6 has been reported with mixed infections with ST7 in birds. According to this subtype report in this study, further researches and revision of the division of the subtype host are necessary (27).

The lack of determination for four subtypes of the 19 positive samples, as reported in previous studies, may be due to genotype diversity, implying that only some of them are known (28). This suggests that further studies are needed to find other genotypes. Finally, it seems that gathering epidemiological data, ie, identification of zoonotic isolates at the subtype level, is needed for a better understanding of the potential animal reservoirs for human infection.