1. Background

Enterococci are pervasive and predominant inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals, found in soil, water and food (1). For many years, they were considered as normal flora and unharmful to man (2). However, over the last years, enterococci have emerged as major nosocomial pathogens, representing an increasingly important problem for public health (3). Indeed, these bacteria have a great ability to acquire resistance to some antimicrobial agents such as glycopeptides, in particular vancomycin, which are important for human therapy (4). Although enterococci are normally of relatively low virulence, they can transfer their antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors to other intestinal microflora and/or virulent bacteria, resulting in an increased pathogenicity (5).

The climbing incidence of antibiotic resistant Enterococcus spp. is the result of increased use of antibiotics in human health care system and animal growth promoters (6). The presence of large numbers of enterococci, in particular multidrug resistant ones, occurs commonly in vegetables, dairy and animal products (7). This dilemma, in part, is because of extensive usage of antimicrobial agents in modern farm industry (8). Due to limited therapeutic options for treating vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), they are considered as a major cause of concern. VRE has been isolated from hospital sources, food animals, environment, and waste water. Previously, we investigated more about VRE from clinical samples, surface water and sewage treatment plants in Iran. The results of our prior studies showed isolation of a high number of VRE isolates from water and sewage (9, 10).

2. Objectives

In view of the lack of information about VRE isolates in food samples, we studied the occurrence of VRE in meat, chicken and cheese which were sold in local markets.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection and Processing

Thirty food samples, each 10 from chicken, meat and cheese were collected from Tehran local markets from April to September 2010. The samples were sealed in a plastic bag, labeled immediately and transported to a microbiology laboratory in a cold cycle. Ten grams of each sample were suspended in 90 mL of saline and then heavily vortexed. The mixture was filtered using 0.45 µ filter membrane (Millipore, Sparks, MD, USA). The filters were then transferred to m-Enterococcus agar (Becton Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with 4 µg/mL vancomycin and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C.

3.2. Identification of Isolates

Colonies suspected to be Enterococcus were subjected to identification tests using the following characteristics: growth and hydrolysis of bile-esculin agar, growth in the presence of 6.5% NaCl, absence of catalase, presence of pyrrolidonyle arylamidase, 0.04% tellurite reduction, arabinose utilization, arginine dehydrolase activity, methyl-a-d-glucopyranoside acidification, and motility and pigmentation. Species identifications were confirmed by PCR using specific primers (11).

3.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Tests

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for vancomycin, teicoplanin and gentamicin were determined using the E test (Biodisk AB, Solna, Sweden). Susceptibility tests to ampicillin (10 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), gentamicin (120 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), chloramphenicol (30 µg), linezolid (30 µg), and quinupristin/dalfopristin (Q-D) (15 µg), (Mast Diagnostics Ltd., Bootle, Merseyside, UK) were performed by disc diffusion method according to the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines (12). Enterococcusfaecalis ATCC29212 was used as control.

3.4. DNA Extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction

All the VRE isolates were investigated for vancomycin resistance genes. For DNA extraction, one isolated colony from each plate was transferred into 200 μL distilled water and boiled at 100°C for 15 minutes. The mixture was centrifuged and 10 μL of the supernatant was used as the DNA template in the PCR mix. Identification of van genotypes (vanA, vanB) for each isolate of VRE was performed by a separate PCR with specific primers as follows: vanA, 5’-CATGAATAGAATAAAAGTTGCAATA-3’, 5’-CCCCTTTAACGCTAATACGATCAA-3’; vanB, 5’-GTGACAAACCGGAGGCGAGGA-3’, 5’-CCGCCATCCTCCTGCAAAAAA-3’. The PCR assay was performed in a total volume of 25 μL containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH = 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTPs, 0.5 U TaqDNA polymerase (HT Biotechnology, Cambridge, UK), and each primer (40 pmol). The PCR cycle was as follows; initial denaturation at 94°C for five minutes, 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for one minute, annealing at 54°C for one minute and extension at 72°C for one minute, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes (13). The PCR was performed with an Eppendorf Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY).

3.5. Typing of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Isolates

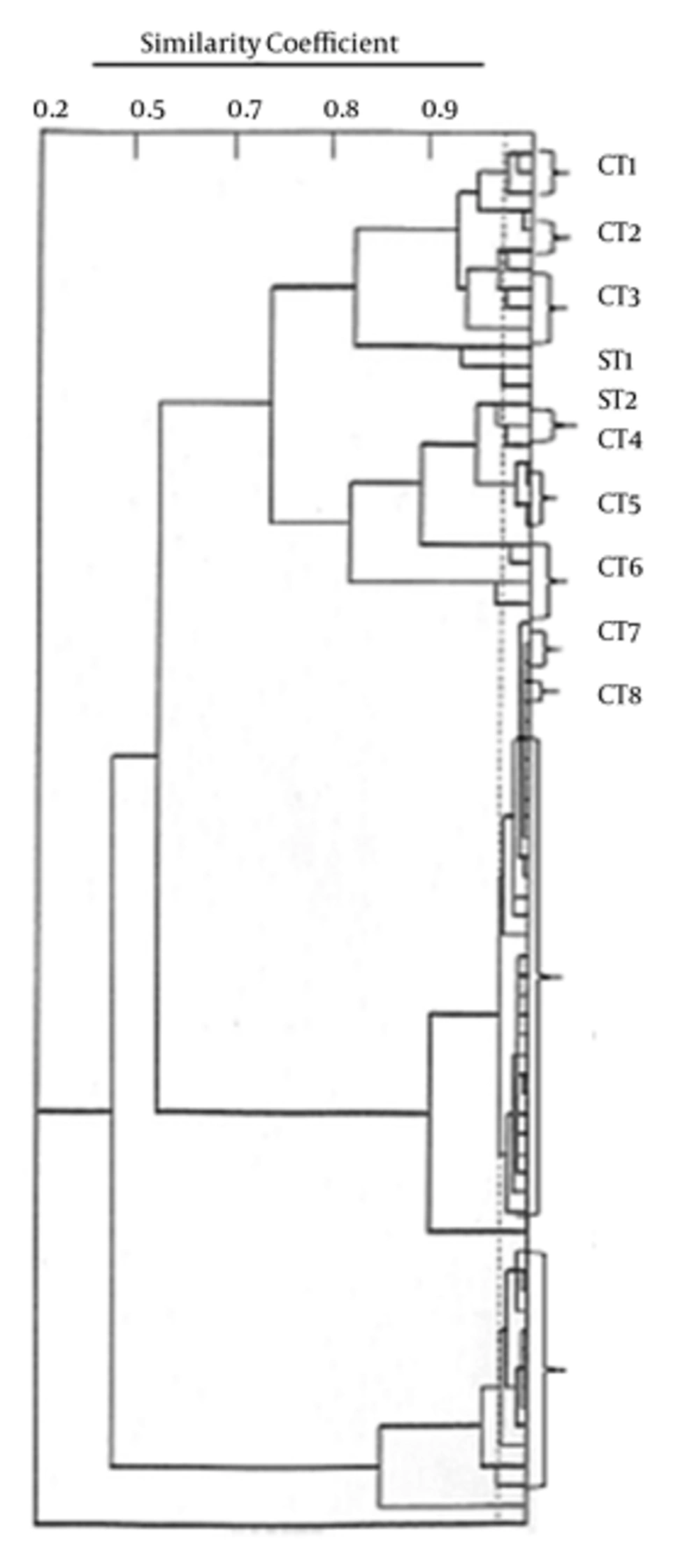

All the isolated VRE were typed using a high-resolution biochemical fingerprinting method, Phene plate (PhPlate) system, which is specifically developed for typing of enterococci strains (The PhPlate AB, Stockholm, Sweden). Microplates with 11 carbohydrate substrates were specifically chosen to differentiate between strains of enterococci. Preparation and inoculation of the plates were according to the manufacturer instruction. Briefly, a loopful of a fresh bacterial culture was inoculated in PhPlate growth media containing 0.2% (w/v) protease peptone, 0.05% (w/v) yeast extract, 0.5% (w/v) NaCl and 0.011% (w/v) bromothymol blue. The plates were then incubated at 37°C and images of the plates were scanned after 16, 24 and 48 hours using an HP Scanjet 4890 scanner. After the final scan, the PhPlate software (PhPWin 4.2) was used to create the absorbance data (biochemical fingerprint) from the scanned images. The correlation coefficient using a pair-wise comparison of the biochemical fingerprints and clustered was determined according to the unweighted pair group method (UPGMA) with arithmetic averages. The mean similarity between the compared isolated minus 2SD was taken as the ID-level of the system. Isolates showing similarity to each other above this level were considered as identical (Common Biochemical Phenotypes: C-BPT) (13).

4. Results

4.1. Vancomycin resistant Enterococci Detection and Identification

According to the biochemical tests, a total of 102 isolates belonged to enterococci, 48, 40 and 14 of which were from meat, chicken and cheese, respectively. Antibiotic susceptibility test revealed that 35, 27 and 8 isolates obtained from meat, chicken and cheese, respectively, were vancomycin-resistant. Conventional and molecular identification tests exhibited that all the isolates were E. faecium carrying vanA. None of the isolates harbored vanB.

4.2. Antibiotic Resistance

Using the method of CLSI, all the isolates were tested for their resistance against antimicrobial agents. All the VRE isolates were susceptible to linezolid, quinupristin-dalfopristin and tetracycline. However, they showed different degrees of resistance to other antibiotics. All the VRE isolates were also resistant to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin and ampicillin (100%). Almost the same antibiotic resistance was observed for gentamicin (95%), but only 5% of the isolates were resistant to chloramphenicol. The MIC of the isolates for vancomycin and teicoplanin was ≥ 256 µg/mL and for gentamicin-resistant isolates it was 1024 µg/mL.

4.3. Typing

The results of typing with PhPlate system showed a diversity of Di = 0.78 for the E. faecium population. A total of 14 types with 10 common types (C-BPT) constituting 66 isolates and four single types (S-BPT) were seen (Figure 1). Each common type comprised 2 - 31 strains. The VRE from the meat samples showed 11 types comprising 35 isolates, while the chicken isolates contained only four types. Some of the isolates collected from different food samples on different sampling occasions were found to have the same C-BPT (Table 1).

| BPT | Number of VRE Isolates | Number of Sampling | Sample Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT1 | 3 | 1,2 | Meat |

| CT2 | 2 | 1,2 | Meat |

| CT3 | 4 | 3,5 | Meat |

| CT4 | 2 | 4,6 | Meat, chicken |

| CT5 | 3 | 1,3 | Meat |

| CT6 | 4 | 1,6 | Meat |

| CT7 | 2 | 2,4 | Meat |

| CT8 | 2 | 1,7 | Meat , chicken |

| CT9 | 31 | 1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9,10 | Meat, chicken, cheese |

| CT10 | 13 | 2,3,4,6,7,8 | Chicken, cheese |

| ST1 | 1 | 3 | Meat |

| ST2 | 1 | 4 | Meat |

| ST3 | 1 | 10 | Cheese |

| ST4 | 1 | 7 | Cheese |

Number of Vancomycin resistant Enterococci Strains in Each Phene Plate Type and Their Sample Types and Number of Sampling a

5. Discussion

A high rate of vanA containing Enterococcus isolates was detected in food samples of chicken (9/10) and meat (10/10) in this study. Isolation of vanA-containing enterococci strains in poultry and fresh slaughtered chicken samples has been reported in Germany (14). Furthermore, high-level glycopeptide-resistant VanA-type strains from supermarket-purchased chicken were detected in England (15). On the other hand, absence of VRE from meats was reported in studies performed in the US (16, 17) which reflected the absence of VRE isolation in animal food product. Elimination of VRE, in part, may have been resulted during the food processing. On the contrary, in European countries, VRE have been frequently isolated from meat products, which might be due to the usage of glycopeptides avoparcin antibiotic in food animal production environments before banning this antibiotic (18, 19). In this study, we obtained similar results to the European countries which may indicate the presence of similar diets in Iran.

Our results showed the presence of enterococci strains in 50% of cheese samples. In contrast, in a study by Giraffa and Sisto, there was no evidence of VRE in dairy products (20). However, some years later, Giraffa and colleagues in Italy found that 50% of the cheeses examined were contaminated by VRE (7). E. faecium was the only species isolated in all the samples in our study, while in most of the studies E. faecium and E. faecalis were simultaneously isolated from food samples. Klein et al. reported a total of 34 VRE strains isolated from raw minced beef and pork and 38% of VRE isolates were identified as E. faecium, 35% were E. faecalis, and the remaining isolates were from the E. faecium group (21). Moreover, similar results were detected in the UK in fresh and frozen chicken, 58% and 40% of which were E. faecium and E. faecalis, respectively (15).

Antibiotic susceptibility tests showed that in the present study, the VRE isolates were resistant to at least four antibiotics including gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin and ampicillin. This has been confirmed by other studies which have found the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant enterococci in farm animals and their meat to be higher than 60% (22, 23). These studies showed that extensive agricultural use of glycopeptides or other antibiotics has created animal reservoir of resistant enterococcal species to antibiotics which has complicated the control of infections caused by enterococci. Here we determined that resistance to gentamicin was very high among the animal products (95%). Using the synergism between aminoglycosides and B-lactams or glycopeptides eliminated owing to high-level aminoglycoside resistance, which is of vast clinical importance (24). Peters and colleagues have reported a very low gentamicin resistance in food from animal origin in Germany (25). The difference in the reported antibiotic resistance among animal products could be due to geographical differences and the policy as well as production practices performed in these countries.

All of our isolates were susceptible to tetracycline, in comparison with the results from Peters and colleagues who found a high rate of tetracycline resistance in their strains (25). The reason for the absence of resistance to tetracycline in this study may be due to the fact that tetracycline is not used as a therapeutic antimicrobial in veterinary medicine in Iran. In consistent with another study, here we reported that the prevalence of chloramphenicol resistance was very low among E. faecium strains (26).We found no resistant isolate to oxazolidinone, linezolid and Q-D in this study (25). Although surveillance of enterococci from food sources for resistance to linezolid has not been reported extensively (26), there are some resistance reports to Q-D in the USA, given the use of the analogue virginiamycin since 1974 (27, 28).

In PhPlate analysis, we found that some of the C-BPT were found on different sampling occasions and food samples (i.e. C8, C9), indicating a high prevalence of certain E. faecium C-BPT in the food. In addition, in another study, typing with PhPlate exhibited a high diversity in a large number of enterococci isolated from different sources including food samples (29). On the other hand, genotyping with Pulse-Field Gel Electrophoresis profile (PFGE) and Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) PCR revealed a marked heterogeneity in food isolates (30, 31). These results also showed that isolates with identical BPT pattern were found in different sampling occasions in the same food sample (i.e. isolates in C10), suggesting that some of the strains persisted for a period of time.

In conclusion, the high prevalence of multidrug resistance among enterococci isolated from food is a serious threat to public health. To the best of our knowledge, there is no use of antibiotic other than human use, in animal feeding in Iran. The data presented here, on the other hand, suggested the presence of antibiotic pressure in food animals. The level of antibiotics in animal product, in turn, may be due to treatment regimens used for infections in animals. Controlled use of antibiotics in animal husbandry is highly suggestive in Iran.