1. Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common chronic viral hepatitis in the world. It is estimated that 350 million carriers exist in the world and around one million of them die annually (1). About 30% of the world population has been exposed to HBV (2). The prevalence of HBV infection varies between different countries. Some geographical regions such as China, southeast of Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa are highly prevalent areas with more than 7% chronic carrier rates, while west-Europe and North American countries have less than 2% chronic carrier rates (low prevalent) (3). The prevalence of HBV infection in Iran varied 2.7% to 7.2 %, but after the national vaccination program it decreased to below 2% (4, 5). Traditionally, chronic HBV infection was expressed as existence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in serum.

Occult HBV infection (OBI) is defined as the presence of HBV DNA in serum, lymphocytes or hepatocytes with undetectable HBsAg in serum (6-8). There are certain evidences that OBI may be accompanied with other chronic liver diseases such as HCV infection, nonalcoholic liver disease, HIV infected cases, and hemodialysis patients (9-13). OBI has been reported as an additional risk factor for progression of alcoholic liver cirrhosis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and HIV infection to hepatocellular carcinoma (14-17). The etiologies of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis are not clear in at least 10% of individuals, so called “cryptogenic liver disease” (18). The prevalence of OBI in cryptogenic chronic liver disease varies 19 - 30%. In a study in Iran, the prevalence of OBI was 1.9% in people with cryptogenic chronic liver disease (19), while in some regions of India, the prevalence of OBI in patients with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis was reported 38% (20). A recent study showed 38% prevalence of OBI in Iranian patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis (21). Usually, the HBV DNA level in patients with OBI is low and currently, PCR is the only available diagnostic tool to detect HBV DNA in sera of patients with OBI (22).

2. Objectives

The aim of the present study was to compare the prevalence of OBI between patients with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis referred to the hepatology clinics of Ahvaz Jundishapur University, and a group of healthy individuals. Ahvaz is the capital of Khuzestan province, located at the southwest region of Iran with a population of 1.5 million.

3. Patients and Methods

In this case-control study, 50 patients with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis, referred to gastroenterology and hepatology clinics of Ahvaz Jundishapur University, were selected during May 2011 to June 2012. Liver cirrhosis was defined if there were compatible liver biopsy or clinical plus imaging and laboratorial evidences in favor of portal hypertension and hepatocellular dysfunction. All the patients underwent comprehensive study to rule out autoimmune, metabolic, drug induced and alcohol-related liver injuries. Viral hepatitis was excluded using negative serological markers for HBV and HCV infections. Cryptogenic liver cirrhosis was defined if the patients had cirrhosis without established specific etiology. The control group was selected from the volunteers who were present in the clinics as relative of patients with non-liver diseases, if they had no risk factor for HBV infection. The proposal was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology of Ahvaz Jundishapur University (code = ETH-335).

3.1. Serology and Biochemical Tests

After blood collection from each patient, the following tests including alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), prothrombin time (PT), bilirubin, serum albumin, complete blood count (CBC) were carried out. The serological HBV markers (HbsAg, HBsAb, anti HBcIgM and anti HbcIgG) tests were performed for each individual and the control group by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Diagnostic BioProbe, Milan, Italy). The serum of the each patient was kept at -80°C prior to performing the PCR tests. Nested PCR amplification assay was used to detect OBI for all the patients as well as the control group (23).

3.2. DNA Extraction

A volume of 200 µL serum of each patient as well as each individual in the control group was used for extraction of the viral DNA, using high pure nucleic acid kit (Roche Applied Sciences, Germany). Nested PCR was applied for amplification of the S region of the HBV DNA gene using the following primers (24): FHBS1 (244 to 267 position), FHBS2 (255 to 278 position), RHBS2 (648 to 671 position), and HBS1R (668 to 691 position). Five microliter of the extracted DNA from each serum sample was added in a 25-µL reaction mixture containing dNTP (10 mM) 0.5 µL, PCR buffer (10 x) 2.5 µL, Taq DNA polymerase 5U (Roche, Germany) 0.15 µL, 50 pmol/µL of both FHBS1 (5'-GAG TCA AGA CTC GTG GTG GAC TTC-3') and RHBS1 (5'-AAA TKG CAC TAG TAA ACT GAG CCA-3') primers, and distilled water 20.35 µL.

Using a thermal cycler (Techneco, UK) for the first round of nested PCR, first amplification was carried out with initial denaturation at 94°C for five minutes and then by denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 56°C for 30 seconds, and extraction at 72°C for 30 seconds for a total of 30 cycles. For the second round, 5 µL of each PCR product was added to a 25-µL reaction mixture, containing dNTP, PCR buffer and Taq DNA polymerase with 50 pmol/µL of each FHBS2 (5'-CGT GGT GGA CTT CTC TCA ATT TTC-3') and RHBS2 (5'-GCC ARG AGA AAC GGR CTG AGG CCC-3') primers. The amplification was carried out in the thermal cycler with the same program for the first amplification. Then, 8 µL of the nested PCR product (417 bp) was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis on 2% gel in 0.5 x TBE buffer.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Pearson chi-Square test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables and students T-test for continuous variables, using SPSS 16 package program for statistical analysis (Chicago, IL, USA). P value more than 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

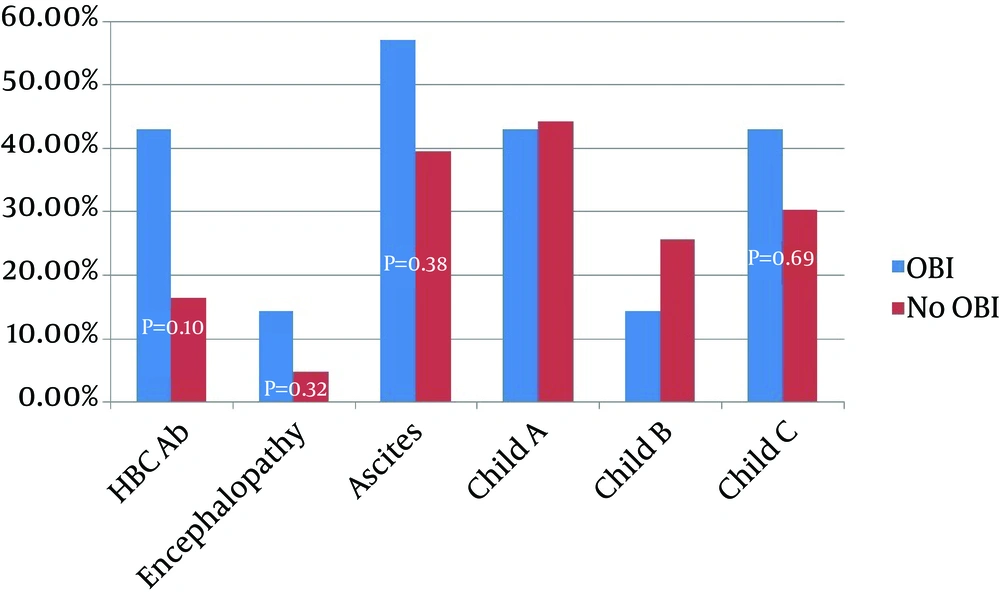

Anti-HBC antibody was detected in serums of 10 (20%) patients with cirrhosis and 8 (10%) healthy subjects (P = 0.10). Anti-HBS antibody was detected in 12 (24%) of cirrhotic and 18 (21%) of healthy subjects (P = 0.84) (Table 2). Seronegative OBI was noted in 4 (57%) of our OBI cases. Three OBI cases had positive anti-HBcAb (two cases of IgG and one case of IgM), but none of them had anti-HBsAb. All the OBI-infected patients were older than 40 years. There were no significant differences in severity of liver dysfunction parameters, transaminases and demographic variables between cirrhotic patients with and without OBI; however, the duration from diagnosis of cirrhosis to the first sign of decompensation was shorter in patients with OBI (1.47 ± 1.283 years vs. 4.327 ± 3.92 years, P = 0.002, 95% CI = -4.585 to -1.230) (Table 3Figure 1).

A total of 165 cirrhotic patients were evaluated. The most common cause of liver cirrhosis was HBV infection (42%), followed by cryptogenic cirrhosis (30.3%) and autoimmune hepatitis (14%) (Table 1). We found 55 cases with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis, but five of them were excluded because of disagreement with blood sampling. Therefore, 50 cases were evaluated in the study; 36 (72%) of them were male and the mean age of the patients was 53.34 ± 14.73 years (Table 2). According to the Child-Pugh scoring system, 22 (44%) of the cases had Child A, 12 (24%) had Child B, and 16 (32%) were in the Child C stage of liver cirrhosis. Eighty healthy subjects including 27 (33.8%) males with a mean age of 32.65 ± 8.51 years were evaluated as the control group and the result of the tests were compared between the two groups.

HBV DNA was found in 7 (14%) sera of the patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis; 5 (71.2%) of cases with OBI were male with a mean age of 54 ± 8.38 years. None of the healthy controls group had HBV DNA in their sera (P = 0.001). Anti-HBc antibody was detected in sera of 10 (20%) cirrhotic patients and 8 (10%) healthy subjects (P = 0.10). HBsAb was detected in 12 (24%) cirrhotic and 18 (21%) healthy subjects (P = 0.84) (Table 2); 4 (8%) of the cases with OBI were seronegative, 2 (4%) had positive anti-HBcIgG and 1 (2%) had anti-HBcIgM, but none of them had HBsAb. All the patients with OBI were older than 40 years. There were no significant differences in severity of liver dysfunction parameters and demographic variables among cirrhotic patients with or without OBI; however, the duration from the initial diagnosis of cirrhosis to the first sign of decompensation was shorter in patients with OBI (1.47 ± 1.283 years vs. 4.327 ± 3.92 years, P = 0.002, 95% CI = -4.585 to -1.230) (Table 3Figure 1).

| Variable | Cryptogenic Cirrhosis (n = 50) | Healthy Control (n = 80) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 53.34 ± 14.73 | 32.65 ± 8.51 | 0.001 |

| Male | 36 (72) | 27 (33.8) | 0.001 |

| ALT IU/L | 39.48 ± 14.73 | 28.40 ± 11.85 | 0.005 |

| AST IU/L | 57.46 ± 25.93 | 24.55 ± 8.49 | 0.0001 |

| HBcAb | 10 (20) | 8 (10) | 0.100 |

| HBsAb | 12 (24) | 18 (21) | 0.843 |

| OBI | 7 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Variable | HBV DNA-Positive (n = 7)b | HBV DNA-Negative (n = 43) b | P Value | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 5 (71.2) | 31 (72.1) | 0.90 | |

| Age, y | 54.00 ± 8.386 | 8.386 ± 15.590 | 0.849 | -11.42 to 12.96 |

| ALT, IU/L | 45.8571 33.363 | 38.441 ± 31.260 | 0.567 | -18.423 to 9.265 |

| AST, IU/L | 73.8571 ± 46.8950 | 54.790 ± 20.438 | 0.071 | -1.671 to 39.80 |

| AlkP, IU/L | 197.857 ± 9.940 | 218.488 ± 58.482 | 0.038 | -40.092 to -1.170 |

| Bilirubin | 1.20 ± 0.472 | 1.353 ± 0.837 | 0.640 | -0.809 to 0.503 |

| Albumin | 3.628 ± 0.419 | 3.630 ± 0.587 | 0.994 | -0.468 to 0.464 |

| PT, s | 15.857 ± 2.1157 | 15.0605 ± 2.59396 | 0.395 | -1.284 to 2.877 |

| FBS, mg/dL | 102.8571 ± 21.95 | 98.860 ± 23.442 | 0.675 | -15.066 to 23.593 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 200.714 ± 13.047 | 197.697 ± 12.279 | 0.553 | -7.126 to 13.160 |

| Time to decompensation, y | 1.47 ± 1.283 | 4.327 ± 3.920 | 0.002 | -4.585 to -1.230 |

Characteristics of Cirrhotic Patients With and Without Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infectiona

5. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated 50 patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis and 80 healthy controls to evaluate the prevalence of OBI in the two groups. We found a prevalence of 14% in patients with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis. All of our OBI cases were over 40 years of age. No patient in the control group was positive for HBV DNA. There have been several studies addressing the prevalence of OBI in Iran with different results. Honarkar et al. evaluated OBI in liver tissues of 35 cases with liver cirrhosis with different etiologies using tissue PCR and reported a prevalence of 22% (25). Kaviani et al. reported a prevalence of 1.9% for OBI in 104 patients with cryptogenic chronic hepatitis using real-time PCR (19). Ramezani et al. reported a prevalence of 3% among 926 high-risk patients, while the prevalence of OBI in the control group was zero (26). Sofian et al. declared a prevalence of 2.1% for patients with OBI, positive for HBcIgG in 531 blood donors; however, they did not perform PCR for seronegative cases (27).

In our study, 4 (57%) of seven cases with OBI were negative for HBcAb and HBsAb (seronegative); 1 (2%) of the patients with OBI was positive for anti-HbcIgM, which may be in the window period of acute HBV infection. In this study, we focused on cryptogenic cirrhosis and selected healthy individuals mainly for validation of our tests. Of the control group, 2 (2.5%) were positive for anti-HBcIgG, but both of them were negative for HBV DNA, which was compatible with other studies in Iran. The prevalence of OBI has been investigated in many countries. While Heringlake et al. (28) did not detect any occult viral infection among 162 presumed cryptogenic liver cirrhosis patients in Germany, Fang et al. (29) reported 28.8% OBI in 159 Chinese patients. Song et al. from Korea tested 1091 HBsAg-negative adults in the general population and found 7 (0.7%) OBI cases including five anti-HBcAb negative subjects. In agreement with our study, almost all the cases with OBI in that study were over 40 years old (30). These findings suggest that the epidemiology of OBI is the same as overt HBV infection and national vaccination program may prevent OBI.

Evidences which show high prevalence of OBI among subjects with high-risk behavior support this hypothesis. The prevalence of OBI has been reported to be 41.1% among four drug abuser in Taiwan and 4.5% in female workers in Turkey (31, 32). Since the viral load in patients with OBI is very low, the estimated prevalence can be affected by the method of HBV DNA testing. Nested PCR is a highly sensitive method for detection of low-level HBV-DNA; it can detect HBV DNA in serum containing more than 19 IU/mL or 0.1 to 0.01 pg/L of HBV-DNA (7, 33), but may give false positive result due to contamination (24). We considered a control group to address the possibility of contamination and false positive result. We did not detect any positive HBV DNA result is samples of the control group, so the estimated prevalence in our study was scientifically valid. There are several explanations for persistence of HBV infection without presence of HBsAg in serum samples, including mutation in the S gene causing different or no antigen production (34-36), antigen-antibody immune complex formation with secondary reduction in HBsAg titer to undetectable level (37), HBV-DNA integration into the genome of hepatocytes, and insensitivity of laboratory tests to detect low level antigenemia.

Superimposed or concomitant infection with other viral agents such as HCV and HDV can decrease the HBsAg titer to undetectable levels, and finally in the setting of acute HBV infection, HBS antigen may be undetectable before the appearance of anti-HBsAb (serologic window period) (38, 39). There are controversial evidences about the role of OBI in progression of liver dysfunction and development of hepatocellular carcinoma (15). While Covolo et al. (40) and Ikeda et al. (41) in separate studies reported an eight-fold increase in the likelihood of chronic liver disease by OBI, Vakili et al. (42) suggested that OBI may be an insignificant entity. In our study, patients with OBI had statistically non-significant more advanced diseases. For example, they had more frequency, ascites, encephalopathy, and Child C stage of liver cirrhosis (P > 0.05) (Figure 1). The duration from the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis to the first sign of decompensation was significantly shorter in infected cases (1.47 ± 1.283 years vs. 4.327 ± 3.92 years, P = 0.002, 95% CI = -4.585 to -1.230) (Table 3). However, the evaluation of these parameters needs greater numbers of positive cases.

In conclusion, our study showed that OBI is common in patients with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis, especially in older patients. It may contribute to rapid progression to liver decompensation; so, we suggest evaluation of cases with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis for OBI. Infected patient should follow closely for complication.

5.1. Study Limitations

Liver biopsy samples were not available for all the cases, so we performed nested-PCR only on serum samples, which may underestimate the prevalence of OBI. The number of positive cases was not sufficient for comparing the clinical implication of OBI on liver cirrhosis.