1. Background

Many chiral drugs which are used together as a racemic mixture might cause catastrophic side effects. Due to this problem, production of single enantiomer drugs is of interest of the pharmaceutical industry. Enantiomerically pure drugs preparation through enzymatic resolution of enantiomers is an attractive subject (1). Extracellular lipase of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica is frequently used as biocatalyst for the resolution of enantiomers in the racemic mixtures (2, 3). In recent years, high-level production of extracellular lipase by Y. lipolytica has been a favorite subject for the researchers (4-6). Y. lipolytica utilizes hydrophobic substrates, including alkanes, fatty acids, fats and oils by activating several enzymes such as lipases/esterases (LIP genes), cytochromes P450 (ALK genes), and peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidases (POX genes). Triglycerides are first hydrolyzed by lipase into free fatty acids, which are then taken up by the cell (7-12).

Depending on the media composition and environmental conditions, Y. lipolytica is able to produce several extracellular, membrane-bound, and intracellular lipases ( 13 , 14 ). Extracellular lipase Lip2 (38.5 kDa) is encoded by LIP2 gene (GenBank Accession No. AJ012632). This gene is responsible for the whole extracellular lipase activity of Y. lipolytica . Extracellular lipase gene (LIP2) encodes a 334-amino acid precursor protein containing the putative 13-amino acid signal sequence (SS), followed by a stretch of four dipeptides (DP); a short 12- amino acid pro-region (PRO), including the Lys-Arg (KR) cleavage site of the KEX2-like XPR6 endo-protease; and the mature 301- amino acid lipase (MATURE). The promoter (P) and terminator (T) regions consisting of 1.06 and 0.97-kbp fragments are situated upstream and downstream from the LIP2 ORF, respectively (see Figure 1) ( 15 , 16 ).

Shown are the putative 13-amino acid signal sequence (SS), followed by a stretch of four dipeptides (DP); a short 12-amino acid pro-region (PRO), including the Lys-Arg (KR) cleavage site of the KEX2-like XPR6 endo-protease; and the mature 301- amino acid lipase (MATURE). Diamonds indicate the positions of the potential signals for asparagine-linked glycosylation (Asn-X-Thr/Ser). The promoter (P) and terminator (T) regions, consisting of 1.06 and 0.97-kbp fragments are situated upstream and downstream from the LIP2 ORF, respectively.

In our previous work, to obtain the yeast strains producing high levels of extracellular lipase, Y. lipolytica DSM3286 was subjected to mutation. Y. lipolytica U6 mutant strain produced extracellular lipase about 10.5fold higher than that of the wild type strain (4).

2. Objectives

The aims of the study were cloning and molecular analysis of extracellular lipase genes from DSM3286 native and U6 mutant Y. lipolytica strains in Escherichia coli to find suitable targets for inverse metabolic engineering and site-directed mutagenesis to achieve high-level extracellular lipase production in Y. lipolytica and other yeasts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Strains and Culture Conditions

Y. lipolytica strain DSM 3286 was obtained from the culture collection of Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ), Germany. The Y. lipolytica U6 mutant strain was obtained by physical mutagenesis (with ultraviolet radiation) from the wild strain DSM 3286 (4). Yeast strains were grown on 50 mL of YPD medium (glucose, 1.5%; yeast extract, 1%; casein peptone, 1%) in 250-mL flasks at 30°C and 200 rpm (8). E. coli strain DH5α (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, MD, USA), used for transformation and amplification of the recombinant plasmid DNA, was grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/mL), when required (17).

3.2. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Genomic DNA from Y. lipolytica strains were extracted by phenol extraction method and then purified DNA was used as a template (18). Primers were designed and checked by OLIGO software (version 5.0, w. Rychlik) and blasted using BLAST facilities available on the NCBI website against the LIP2 nucleotide sequence from Y. lipolytica strain DSM3286 (GenBank Accession No. HM486899). Primers were as follows: Ylip2START (5'-ACGGGATCCATGAAGCTTTCCACCATCC-3') with BamHI restriction site as the forward primer and Ylip2STOP (5'-TCCGAATTCCGCTTAGATACCACAGACACCCTC-3') with EcoRI restriction site as the reverse primer (Figure 1).

PCR amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with a final volume of 50 µL containing 5 µL 10 × buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9, 500 mM KCl, and 15 mM MgCl2), 200 mM dNTP (200 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP), 30 - 60 ng of template, 50 pmol of appropriate primers, and 0.5 U of Pfu (Fermentas, Canada) DNA polymerase. Twenty five PCR cycles were carried out with the following program: denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 min/kbp (4).

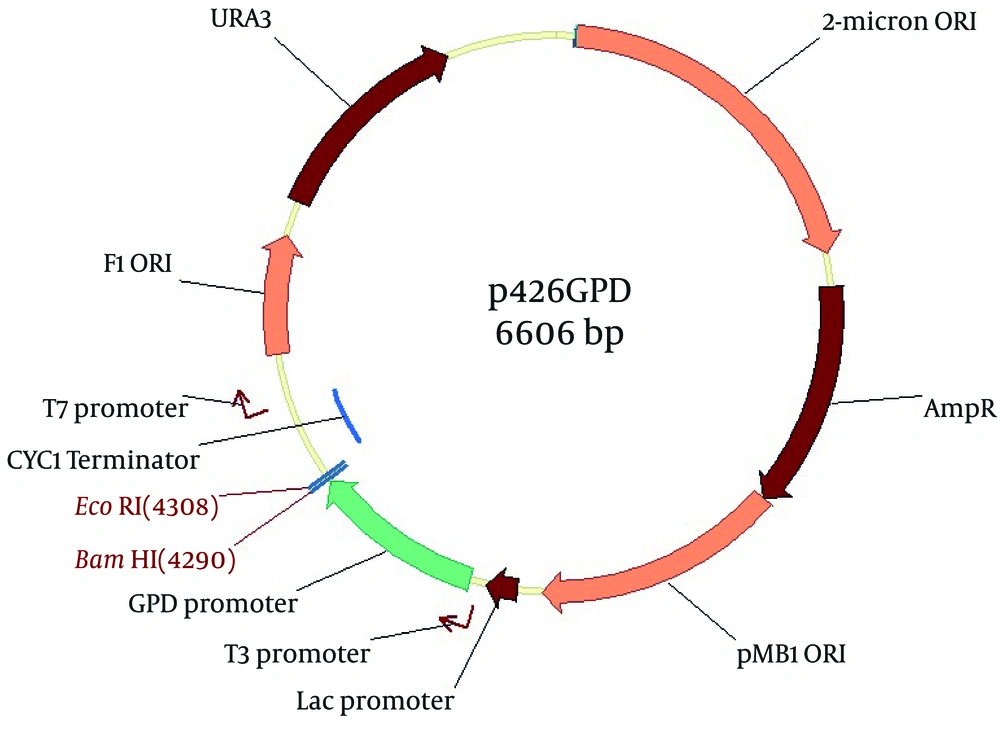

3.3. Construction of New Vector Containing LIP2 Gene

Saccharomyces cerevisiae expression vector p426GPD (Yeast 2 µ expression vector with GPD promoter and URA3 marker; GenBank Accession No. DQ019861) was used in this work (Figure 2). DNA fragments and PCR products were recovered from the agarose gels using an AccuPrep Gel Purification Kit (Cat. No. K-3035; Bioneer, South Korea). The purified PCR products and S. cerevisiae expression vector p426GPD were digested with BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzymes, and then ligated using T4 ligase (17, 19).

GPD promoter, glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase promoter; Lac promoter, lac promoter; T3 promoter, T3 phage promoter; T7 promoter, T7 phage promoter; AmpR, ampicillin resistance gene; URA3, URA3 marker; 2-micron ORI, Yeast 2 µ expression replication origin; pMB1 ORI, origin replication of E. coli; F1 ORI, origin of replication.

3.4. Transformation of E. coli

Competent cells of E. coli were prepared by calcium chloride treatment, and then the vector was transformed into the competent cells using the heat shock method. Alkaline lysis method was used to isolate the vector from the transformed E. coli cells (18).

3.5. DNA Sequencing

DNA was sequenced on an automated sequencer (ABI 3730 XL, PerkinElmer Biosystem) using synthetic primers and the dye terminator procedure (Bioneer, South Korea).

4. Results

4.1. Cloning of the LIP2 Gene From Native and Mutant Y. lipolytica Strains

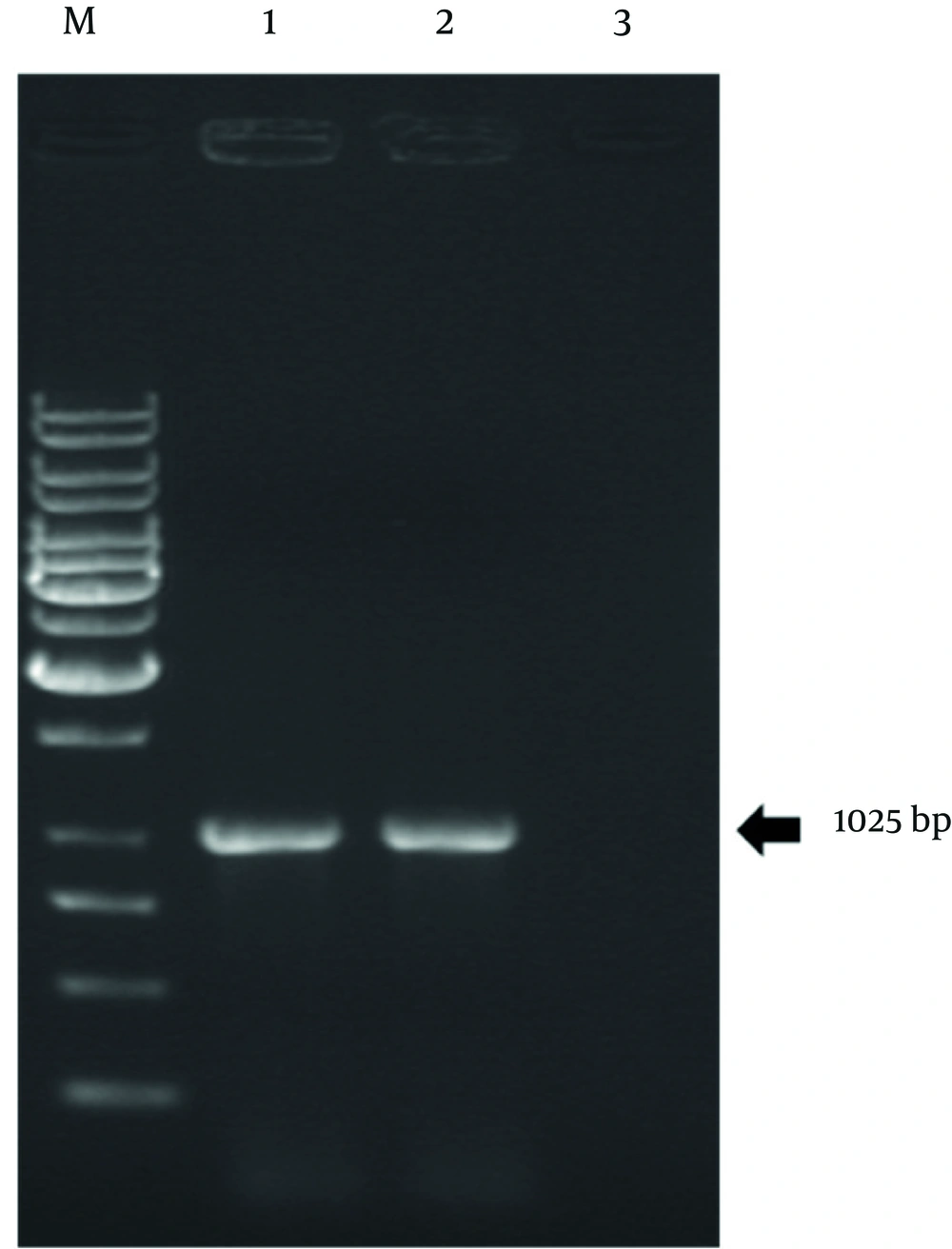

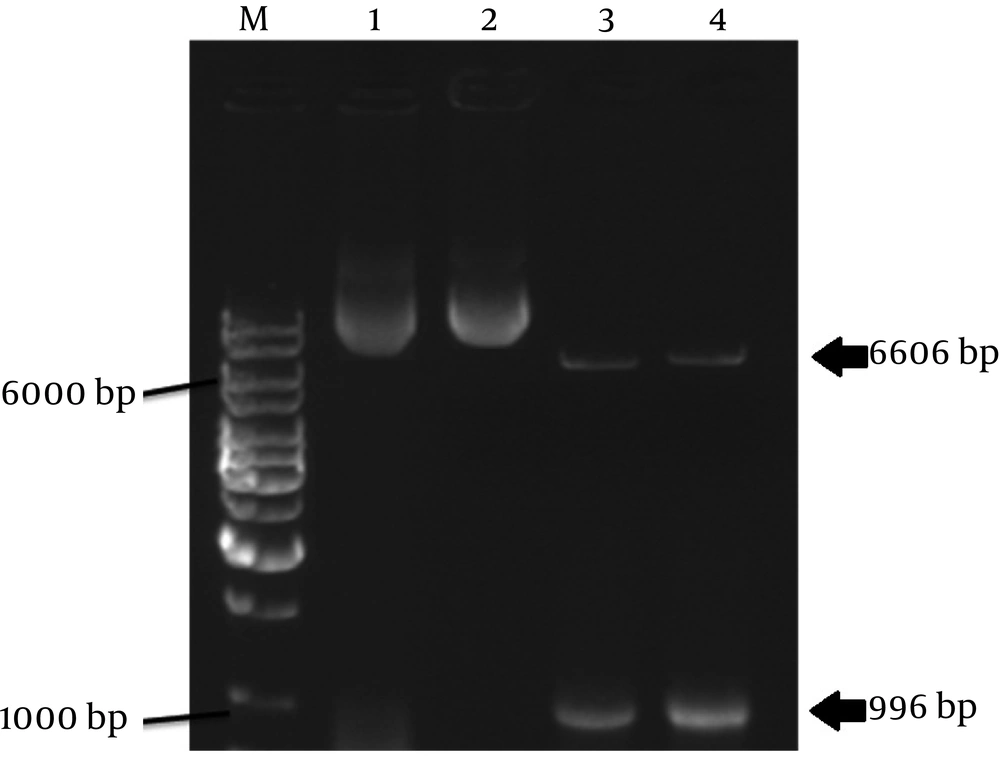

Genomic DNA strands lipolytica were extracted from native and mutant Y. lipolytica strains by phenol extraction method. The concentration and purity of the total DNAs were analyzed by spectrophotometer and gel electrophoresis. The purified DNA then was used as a PCR template. The forward primer Ylip2START with BamHI restriction site and the reverse primer Ylip2STOP with EcoRI restriction site were used for PCR amplification of native and mutant LIP2 genes from Y. lipolytica DSM 3286 native strain and Y. lipolytica U6 mutant strain, respectively. The results are shown in Figure 3.

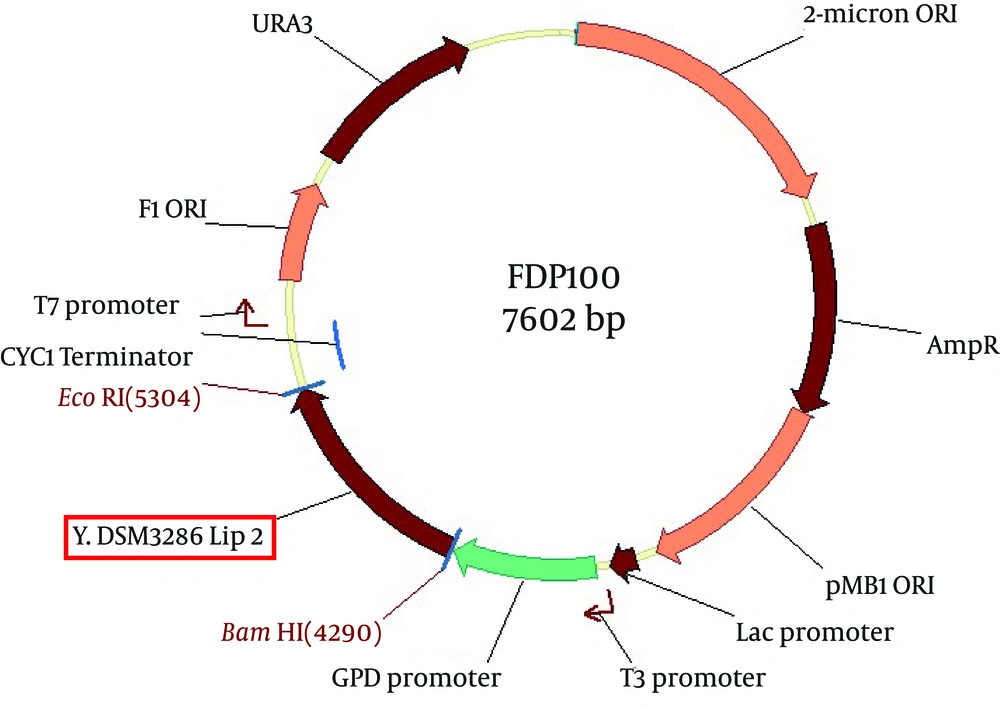

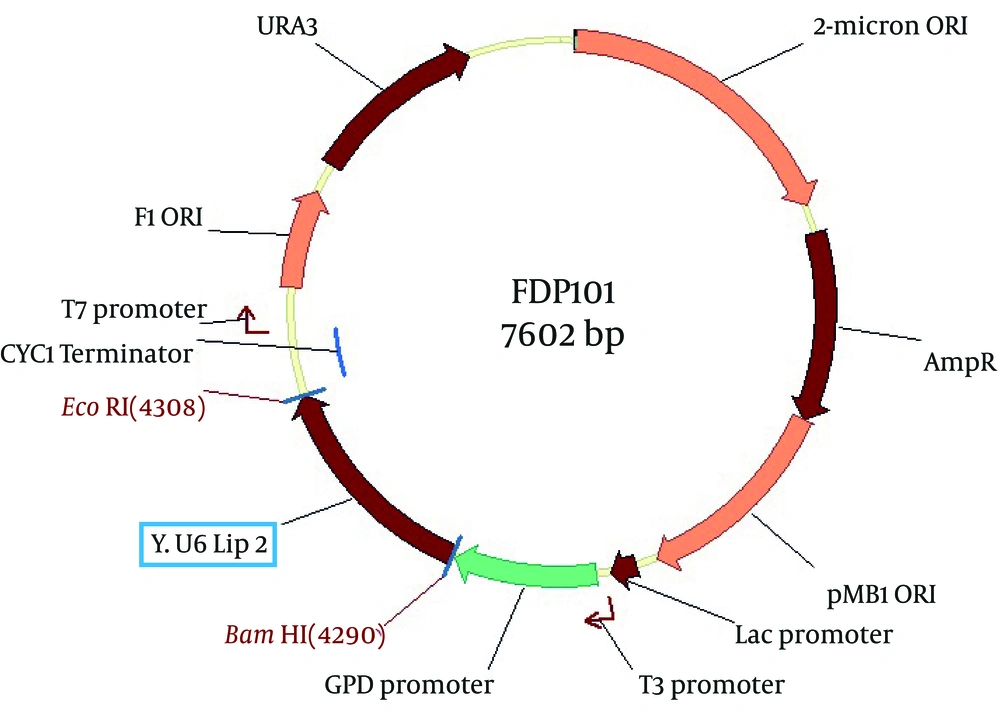

The PCR products and p426GPD vector were digested with BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzymes. They got recovered from the agarose gels and then ligated using T4 ligase enzyme with the proper ratio. The resulting constructs, designated as pFDP100 and pFDP101, contained the native and mutant LIP2 gene, respectively (Figures 4 and 5).

The new vectors were transformed to competent cells of E. coli DH5α strain, and then the new recombinant E. coli cells containing native and mutant extracellular lipase enzymes were named E. coli FDE100 and FDE101, respectively.

4.2. Analysis of Y. lipolytica Native and Mutant LIP2 Genes

The vectors were isolated from the transformed E. coli cells by alkaline lysis method after being grown of E. coli FDE100 and FDE101 on Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin. Afterwards, correct structure of the new vectors and the presence of extracellular lipase genes in the vectors were checked by restriction endonuclease digestion (Figure 6) and PCR methods (data not shown).

The native and mutant extracellular lipase ORFs were sequenced for further analysis and finding the differences in the nucleotide sequences. Results of the sequencing were blasted using BLAST facilities available on NCBI website. Sequence alignment of the extracellular lipase LIP2 ORFs from Y. lipolytica DSM3286 and U6 strains show that the C nucleotide of the position 362 was substituted with a T nucleotide and the A nucleotide at the position 385 was substituted with a T nucleotide in the extracellular lipase LIP2 ORFs of Y. lipolytica U6 mutant strain compared to the wild-type strain (data not shown).

5. Discussion

Overexpression of the extracellular lipase in Y. lipolytica was initially achieved by two different approaches. In the Nicaud group, LIP2 gene was cloned under the control of the strong, oleic acid-inducible POX2 promoter, using multiple copies of the gene. The resulting strains were actually constructed by metabolic engineering, producing unstable amounts of lipase on the expensive laboratory medium. In the Thonart's group, overproducing mutants were isolated from the wild-type strain CBS6303 by successive rounds of chemical mutagenesis using N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine. This led to the selection of the second-generation mutant LgX64.81, which produced stable amounts of lipase in the cheap medium and is now used as an industrial strain (20).

Inverse metabolic engineering by elucidation of a metabolic engineering strategy involves the following steps: first, identifying, constructing, or calculating a desired phenotype; second, determining the genetic or the particular environmental factors conferring that phenotype; and third, endowing that phenotype on another strain or organism by directed genetic or environmental manipulation (21). Now, inverse metabolic engineering is a good strategy in microbial enzyme biotechnology. To successfully attain the inverse metabolic engineering of Y. lipolytica extracellular lipase lipolytica, in the first step, we constructed the high-level lipase producer strain U6 by UV mutagenesis that resulted in a 10.5-fold-higher lipase production compared to the wild-type strain DSM3286, and could be used in the industrial scale (4). The effects of genetic changes in LIP2 expression must be analyzed stepwise in a suitable host. To address this problem, the ORF regions of the mutant and native LIP2 were selected for cloning in E. coli.

In this study, S. cerevisiae expression vector p426GPD containing a strong constitutive glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD) promoter was used for LIP2 gene expression (Figure 2). The native LIP2 gene from Y. lipolytica DSM3286 and the mutant LIP2 gene from the mutant Y. lipolytica U6 were cloned into the vector without any modifications. Sequence analysis showed strict identity between the LIP2 sequences of Y. lipolytica DSM3286 and its mutant strain U6. However, only two silent substitutions at the positions 362 and 385 were observed in the ORF region of LIP2 gene. Fickers et al. detected a single silent substitution of T for C at the LIP2 coding region as well as six single substitutions and duplication of the ACAGATCAT sequence in the promoter region of the industrial mutant strain LgX64.81 (22).

In this study and previous studies, some genetic changes of the LIP2 ORF region were found in the high-level extracellular lipase producer Y. lipolytica mutant (22). Therefore, these genetic changes are suitable targets for inverse metabolic engineering and site-directed mutagenesis of high-level extracellular lipase production in Y. lipolytica and other similar organisms. Y. lipolytica yeast produces different lipases, thus the analysis of the LIP2 ORF region genetic changes is so difficult in this microorganism. S. cerevisiae cannot produce extracellular lipase and utilizes low-cost lipid substrates (23). Hence, new vectors constructed in this study using the S. cerevisiae expression vector p426GPD, could be used to target the expression in S. cerevisiae in the future. The results will help us construct recombinant oily-substrate-consumer S. cerevisiae strains, and compare the LIP2 ORF region genetic changes of the native and mutant Y. lipolytica extracellular lipases in S. cerevisiae.