1. Background

Hepatitis B is a global health problem. According to the World Health Organization report, about 350 million individuals are infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and 650,000 patients die due to hepatitis B complications, annually. The spectrum of clinical manifestations of hepatitis B varies between the asymptomatic carrier state and chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (1). Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) consists of two phases: early replicative phase with active liver disease and non- or low-replicative phase with normal liver function (2). During the initial phase of chronic HBV infection, the patients have HBeAg and high levels of HBV DNA in their blood serum (3). The early-replicative phase is predominantly observed in patients who prenatally acquired the infection. The majority of HBeAg-positive patients have high serum HBV DNA and normal alanine transaminase (ALT) levels and show minimal changes on liver biopsy (immune tolerance (IT) phase).

Most of the patients in the IT phase develop CHB with high HBV DNA and ALT levels in their later life (immune clearance (IC) phase) (4). Among patients in the IC phase, the annual rate of HBeAg clearance is about 8% to 12%. After HBeAg seroconversion, some patients enter the non- or low-replicative phase which is characterized by normal serum ALT concentration, absence of HBeAg and presence of anti-HBeAb, low or undetectable HBV DNA in serum, and minimal or no histological changes on liver biopsy while, some cases continue to have moderate levels of HBV replication and high levels of ALT with moderate to severe changes on liver biopsy in the absence of HBeAg. This presentation can be explained by the presence of HBV variants with mutations in the precore or basal core promoter regions (5). Precore and basal core promoter variants were observed more in HBV genotype D, which was found to be the most prevalent isolated genotype of HBV from patients in Iran (6, 7). These cases usually have more progressive forms of liver disease than HBeAg-positive patients (8). Recently, a quantitative HBsAg assay has been introduced for evaluation of treatment response to interferon and assistance in diagnosis of HBV clinical stages.

2. Objectives

In this study, we aimed to assess different laboratory and histological characteristics of HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive CHB.

3. Patients and Methods

The present study included a total of 151 treatment naive patients with CHB, who were referred to the Tehran Blood Transfusion Hepatitis Clinic (Tehran, Iran) from 2011-2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients whom participated in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 declaration of Helsinki. The criteria for diagnosis of CHB were the presence of HBsAg in the patient’s serum for more than six months, HBeAg positivity or serum HBV DNA > 20,000 IU/mL, persistent or intermittent elevation in ALT/aspartate transaminase (AST) levels, and/or liver biopsy showing chronic hepatitis with moderate to severe necroinflammation (9).

Individuals with positive serology for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis D virus, and hepatitis C virus were excluded from the study. Also, patients with inactive HBV carrier state were excluded. The study population was divided into two study groups of HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive CHB. Laboratory assessments including liver function tests, HBV DNA and HBsAg quantification (HBV DNA and HBsAg levels) were assessed for the study population. Upper normal limit of ALT was considered 34 IU/L for non-overweight women (BMI of less than 25) and 40 IU/L for non-overweight men (10). Hepatitis B virus DNA level using COBAS TaqMan HBV test (Roche Diagnostics), HBsAg level using HBsAg II quant assay (Roche Diagnostics) and liver biopsy (the results were reported by hepatitis activity index or grading and fibrosis scores or staging according to the scheme introduced by Ishak) were assessed (11). On liver biopsy, liver fibrosis score (stage) ≤ 2 and liver necroinflammation score (grade) ≤ 4 were considered as cutoff values to show mild liver damage (12).

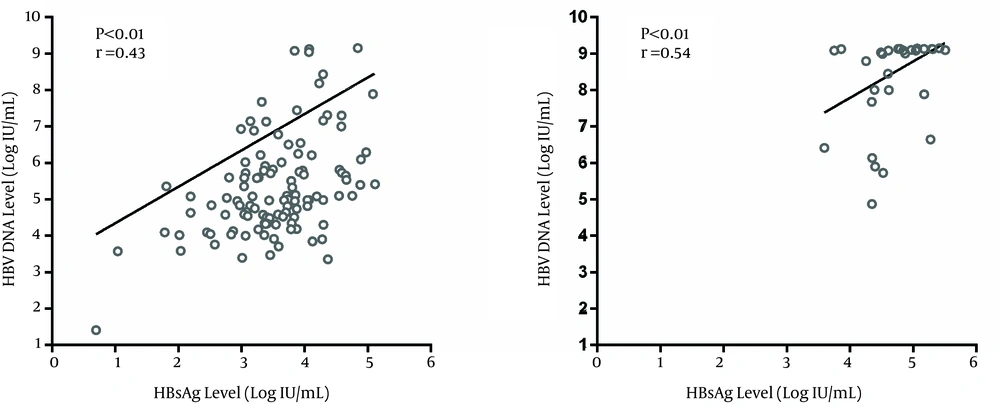

The liver histological assessment was not obligatory for stratification of liver disease in patients with high HBV DNA level (> 20,000 IU/mL) and/or ALT of more than two folds of upper normal limit since the diagnosis of CHB was definite in these patients (9). Comparison between categorical variables was performed using Fisher’s exact test and comparison between continuous variables was performed using t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. The correlation between HBV DNA and HBsAg levels were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software version 20. Also, statistical graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism version 6.

4. Results

In this study, among the 151 treatment naive CHB patients, 121 (80.1%) were HBeAg-negative and 30 (19.9%) were HBeAg-positive. Among HBeAg-positive patients, five cases were in the IT phase and 25 were in the IC phase. HBeAg-negative patients were generally older than HBeAg-positive cases (P < 0.01). There was no statistically significant difference in sex, liver inflammation and fibrosis, serum AST, ALT and bilirubin between the two study groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1). The proportion of patients with moderate to severe fibrosis on liver biopsy was higher in HBeAg-negative cases than HBeAg-positive patients yet this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.29) (Table 1). Hepatitis B virus DNA and HBsAg levels were significantly higher in HBeAg-positive CHB cases than in HBeAg-negative CHB patients (P<0.01) (Table 1). Ninety percent of HBeAg-positive patients had HBV DNA and HBsAg levels higher than 6 log 10 IU/mL and 4 log 10 IU/mL, respectively whereas, around 25% of HBeAg-negative cases had HBV DNA and HBsAg levels above 6 log 10 IU/mL and 4 log 10 IU/mL, respectively (P < 0.01). Hepatitis B virus DNA and HBsAg levels correlated in both HBeAg-negative (r = 0.43, P < 0.01) (Figure 1a) and HBeAg-positive patients (r = 0.54, P < 0.01) (Figure 1 b).

| All Patients (n = 151) | HBeAg-Negative Patients (n = 121) | HBeAg-Positive Patients (n = 30) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.82c | |||

| Male | 110 (72.8) | 89 (73.6) | 21 (70.0) | |

| Female | 41 (27.2) | 32 (26.4) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Age, y | 40.9 ± 14.2 | 43.5 ± 13.4 | 30.5 ± 13.0 | < 0.01d |

| Liver fibrosis | 0.29c | |||

| Mild | 77 (57.0) | 59 (54.6) | 18 (66.7) | |

| Moderate to severe | 58 (43.0) | 49 (45.4) | 9 (33.3) | |

| Liver inflammation | 0.35c | |||

| Mild | 49 (38.9) | 42 (41.2) | 7 (29.2) | |

| Moderate to severe | 77 (61.1) | 60 (58.8) | 17 (70.8) | |

| Serum ALT | 0.25c | |||

| Normal | 40 (26.5) | 35 (28.9) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Abnormal | 111 (73.5) | 86 (71.1) | 25 (83.3) | |

| Serum ALT, IU/L | 68.3 ± 49.3 | 69.0 ± 53.3 | 63.4 ± 27.4 | 0.42d |

| Serum AST, IU/L | 45.8 ± 26.4 | 46.7 ± 28.1 | 41.5 ± 17.6 | 0.33d |

| Serum direct bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.4±0.3 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.08d |

| Serum total bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.07d |

| HBV DNA level, Log IU/mL, Median (IQR) | 5.5 (7.2) | 5.1 (6.0) | 9.0 (9.1) | < 0.01e |

| HBsAg level, Log IU/mL, Median (IQR) | 3.8 (4.7) | 3.6 (4.0) | 4.6 (5.0) | < 0.01e |

5. Discussion

Different studies have reported that HBeAg-positive CHB patients had higher HBV viral load than HBeAg-negative CHB cases (13, 14). In the present study, HBV DNA and HBsAg levels were significantly higher in HBeAg-positive than in HBeAg-negative CHB cases. In the study by Chu et al. (15), among CHB patients, HBV DNA level of more than 20,000 IU/mL was detected in 96% of HBeAg-positive cases. In our study, a significant proportion of HBeAg-positive patients had HBV DNA levels of more than 6 log 10 IU/mL while a small proportion of HBeAg-negative patients had HBV DNA levels of more than this cutoff value. Other studies demonstrated that HBsAg levels were higher in IT-patients and IC-patients compared to patients in low-replicative and HBeAg-negative CHB phases (16, 17).

In the present study, we did not find any significant difference in ALT, AST and bilirubin levels between the two studied groups. A previous study reported higher levels of ALT, AST and bilirubin in HBeAg-negative CHB patients compared to HBeAg-positive CHB individuals (18) whereas, a Chinese study showed higher levels of ALT in HBeAg-positive CHB than in HBeAg-negative CHB individuals (19). Although we found no significant difference in inflammation and fibrosis on liver biopsy according to the patients’ HBeAg status, HBeAg-positive patients had lower fibrosis score than HBeAg-negative patients. A study from China found that hepatic necroinflammation grading and fibrosis staging in the HBeAg-negative group were more advanced than in the HBeAg-positive group (19). In another study, the HBeAg status had no association with the grade of liver inflammation and the stage of liver fibrosis in CHB patients (20).

It seems that there is a correlation between serum HBsAg and HBV DNA levels although the results regarding this issue are conflicting. We found a positive correlation between HBV DNA and HBsAg levels in both studied groups. The studies by Chan et al. (21) and Ramachandran et al. (22) showed that there was a stronger correlation between HBV DNA and HBsAg levels in HBeAg-positive CHB patients than in the HBeAg-negative CHB patients. In another study, there was a correlation between serum HBV DNA and HBsAg levels only during the IC phase (23). According to a study from Iran, there was no correlation between HBV DNA and HBsAg levels in CHB patients (24). On the other hand, in a European study, there was a correlation between HBsAg and HBV DNA levels in patients infected with HBV genotype D but no such correlation in patients infected with HBV genotype A (16). The main limitation of our study was the small number of HBeAg-positive patients, especially patients in the IT phase. The reason for this limitation was the low percentage of HBeAg positivity among Iranian HBV-infected patients. We propose a study with a larger sample size of HBeAg-positive cases who are in the IT and IC phases.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive CHB patients are distinct considering HBV DNA and HBsAg levels.