1. Background

Staphylococcus aureus is a commensal and a major opportunistic pathogen that causes a wide variety of diseases in humans and animals, with a high impact on public health and the livestock industry (1, 2). This organism is recognized worldwide as a major pathogen causing mastitis in lactating cows, sheep and goats (3). Although the udder is considered to be the main source of infection, other areas such as the nares are probable sources of contamination for udder and milk in dairy farms (4). Recently, isolation of S. aureus from the nares of farm animals has been frequently reported (5-7).

Antimicrobial resistance profile of S. aureus is also of great concern. β-lactams, macrolides and tetracyclines are commonly used antibiotics for the treatment of staphylococcal infections and the level of resistance to these antibiotics is growing quickly among staphylococci (8). Resistance genes for penicillin (blaZ, which encodes β-lactamase), methicillin (mecA, which encodes a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein [PBP2a]), erythromycin (ermA and ermB, which encode ribosomal methylases), and tetracycline (tetK and tetM, which encode a tetracycline efflux pump and a ribosomal protection protein, respectively) have been frequently reported among isolates of S. aureus (9-11).

Several studies have provided evidence of transmission of antibiotic-resistant S. aureus (of particular concern Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)) among animals, farm environments, and farmers (12-14). Additionally, transfer of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to humans (or their resistance genes) via the food chain (15), poultry (16), meat and dairy products (17, 18), has already been reported. This may represent a zoonotic risk factor for human colonization or difficult-to-treat infections. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to detection of antibiotic-resistant S. aureus in order to achieve an effective treatment for S. aureus infections. In human medicine, S. aureus nasal carriage has been extensively studied in patients and healthy individuals (19, 20). In Iran, resistance and nasal carriage of S. aureus in healthy children (21) and health care workers (22) have also been studied. The latter research also concluded that S. aureus could be transmitted from health care workers to hospitalized patients. However, neither the S. aureus nasal carriage rate nor its antimicrobial susceptibly patterns are known in ruminants.

2. Objectives

The aims of the present study were to determine the frequency of nasal carriage of S. aureus among healthy ruminants and to investigate the genes involved in resistance to penicillin (blaZ), methicillin (mecA), tetracycline (tetK and tetM) and erythromycin (ermA and ermC) by the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

During the period between January 2011 and May 2012, a total of 201 nasal swab samples were taken from healthy ruminants including 79 cattle, 78 sheep and 44 goats housed in three different areas (Khorramabad, Noor Abad, and Urmia) of Iran. For all animals, cotton swabs were inserted into the anterior nares of both left and right nostrils and were softly rolled against the inner walls. The Urmia University of Veterinary Ethical Committee approved the animal protocol for this study (K2-427). One swab was used to take a sample from both nostrils and then stored in Tryptone Soy Broth (TSB) (Merck, Germany) at 4°C prior to laboratory analysis. Cultures were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and then streaked directly on plates of Mannitol Salt Agar (MSA) (Merck, Germany) and incubated at 37°C for 18 to 48 hours (23). The suspected S. aureus colonies were purified on sheep blood agar plates and then identified by standard biochemical tests including Gram staining, catalase reaction, oxidase reaction, mannitol fermentation and coagulase production (24). Staphylococcus aureus isolates were stored in TSB containing 15% glycerol at -20°C until needed.

3.2. DNA Extraction

For DNA extraction, S. aureus isolates were grown over night at 37°C in Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI, Merck, Germany). Cells were pelleted and suspended in 200 μL of sterile Tris-Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TE) buffer (pH 8.0). Next, DNA was extracted using the Genomic DNA purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, Germany) with some modifications. The extracted DNA was then stored at -20°C.

3.3. Genotypic Determination of Staphylococcus aureus

Identification of the S. aureus species was confirmed by PCR amplification of the nuc gene using primers and protocol described by Brakstad et al. (25).

3.4. Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification of the Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Polymerase Chain Reaction amplification of antibiotic resistance genes was carried out in a CORBETT thermocycler (Model CP2-003, Australia) using PCR master kit (SinaClon, Iran) with 25 μL mixtures including 12.5 μL of 2X master mix, 1 μM of each primer and 4 μL of extracted DNA. Sterile water was added instead of nucleic acids for the negative control. The mecA PCR program included denaturation at 94°C for five minutes followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for one minutes. A final extension at 72°C for five minutes completed the amplification (26). The blaZ amplification was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for five minutes followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds with a final extension of 72°C for 10 minutes (27). The PCR conditions for tet (K and M) and also erm (A and C) genes were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for three minutes followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds with a final extension at 72°C for four minutes (28). The PCR primers used to detect the studied antibiotic resistance genes were synthesized by the SinaClon Company of Tehran, Iran (Table 1).

| Target Gene | Sequence 5' - 3' | PCR Product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| mecA | |||

| F | AAAATCGATGGTAAAGGTTGGC | 532 bp | (26) |

| R | AGTTCTGCAGTACCGGATTTGC | ||

| blaZ | |||

| F | AAGAGATTTGCCTATGCTTC | 518 bp | (27) |

| R | GCTTGACCACTTTTATCAGC | ||

| tetK | |||

| F | GTAGCGACAATAGGTAATAGT | 360 bp | (28) |

| R | GTAGTGACAATAAACCTCCTA | ||

| tetM | |||

| F | AGTGGAGCGATTACAGAA | 158 bp | (28) |

| R | CATATGTCCTGGCGTGTCTA | ||

| ermA | |||

| F | AAGCGGTAAACCCCTCTGA | 190 bp | (28) |

| R | TTCGCAAATCCCTTCTCAAC | ||

| ermC | |||

| F | AATCGTCAATTCCTGCATGT | 299 bp | (28) |

| R | TAATCGTGGAATACGGGTTTG |

3.5. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

The PCR products were separated on 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) containing 0.5 µg/mL ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). Electrophoresis was performed in 0.5x Tris/Borate/EDTA (TBE) buffer at 100 V for one hour. The resulting PCR products were visualized under UV light using a transilluminator (BTS-20M, Japan) and the 100 bp DNA ladder plus was used as the molecular size marker.

4. Results

Among the 201 nasal samples of ruminants tested in this study, 26 were positive for S. aureus recovery. The amount of S. aureus-positive nasal swabs corresponding to cattle, sheep and goats were four (5.06%), 11 (14.1%) and 11 (25%) isolates, respectively.

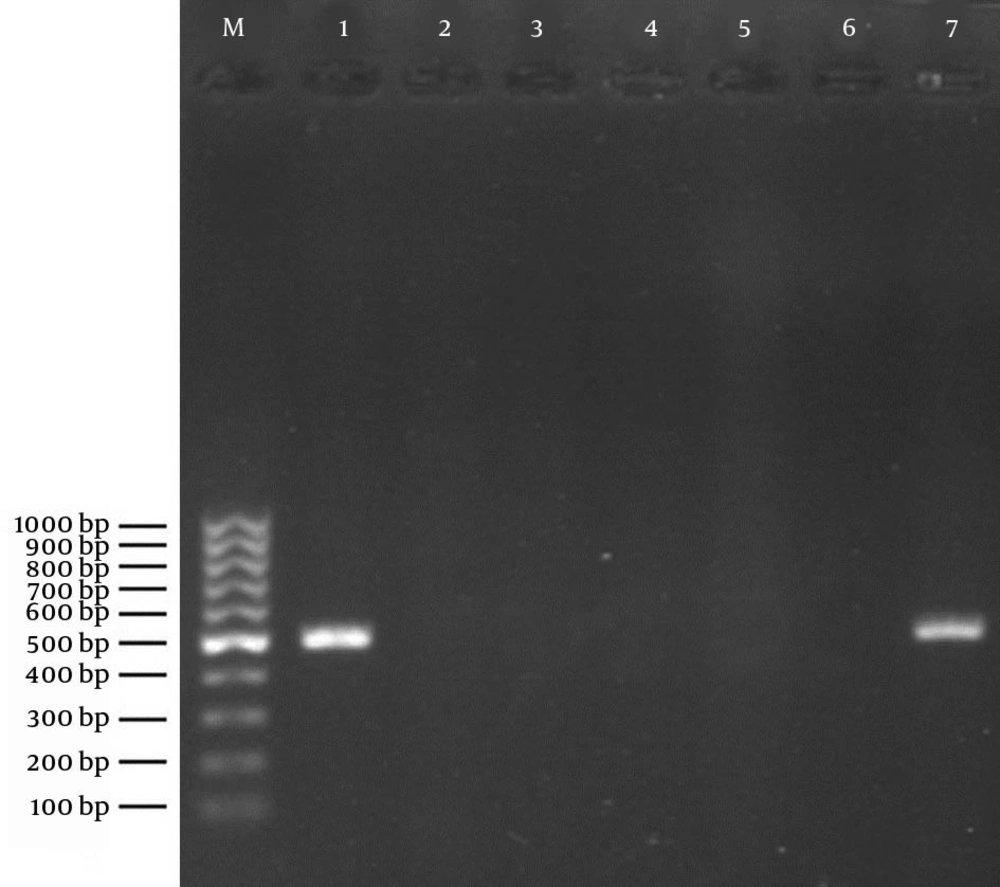

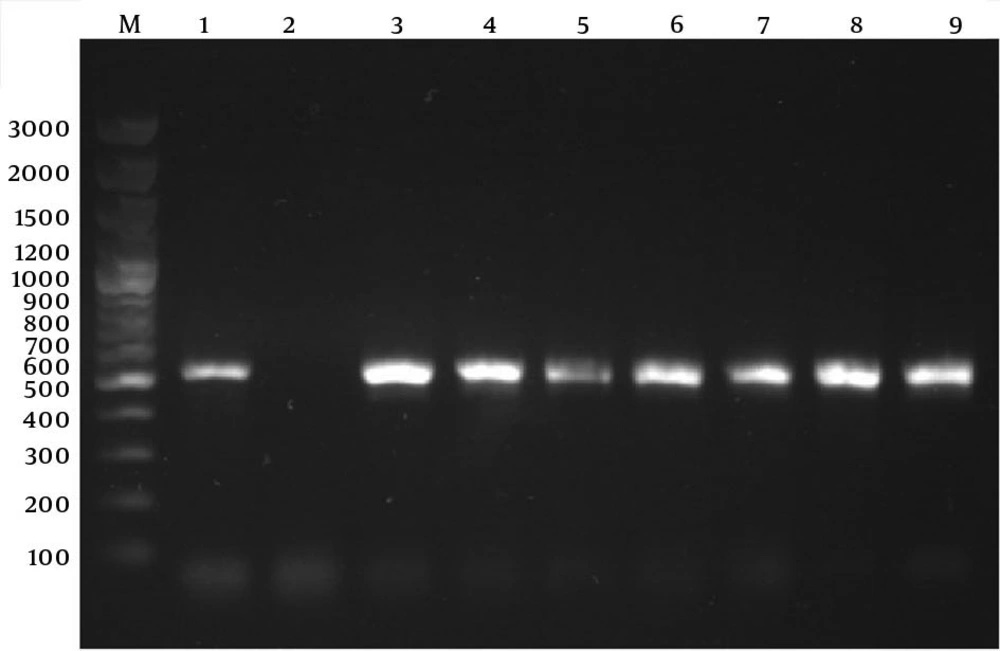

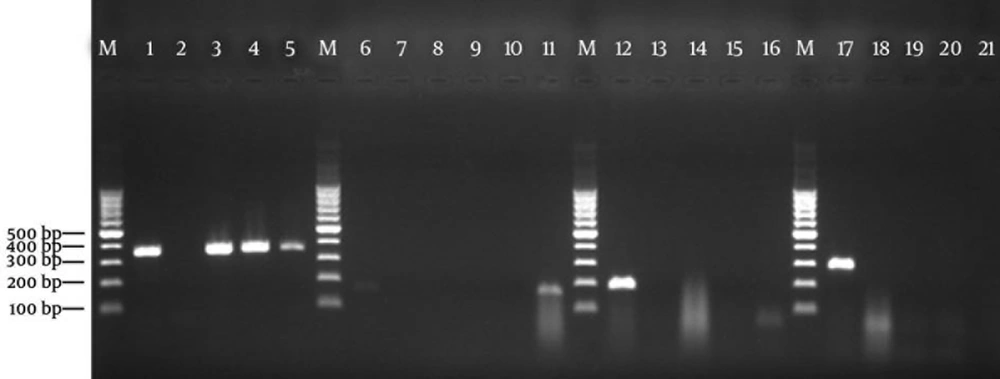

Using the PCR assay, detection of determinants of resistance to methicillin (mecA), penicillin (blaZ), tetracyclines (tetK and tetM), and MLSB (ermA and ermC) was done through successful amplification of a unique DNA fragment of the expected sizes (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Lane M: 100 bp DNA marker (Fermentas, Germany); Lane 1: positive control of amplified 532-bp DNA (S. aureus ATCC 33591); Lane 2: negative control (reaction mixture without DNA); Lanes 3 - 6: representative S. aureus nasal isolates negative for mecA; Lane 7: the only S. aureus isolate positive for the mecA gene.

Lanes M: 100 bp DNA marker (Fermentas, Germany); Lane 1: positive control for tetK gene of amplified 360-bp DNA (S. aureus ATCC BAA-39); Lane 2: negative control (reaction mixture without DNA); Lanes 3 - 5: S. aureus isolates positive for tetK gene; Lane 6: positive control for tetM gene of amplified 158-bp DNA fragment (S. aureus T0131); Lane 7: negative control (reaction mixture without DNA); Lanes 8 - 10: representative S. aureus nasal isolates negative for tetM; Lane 11: the only S. aureus isolate positive for tetM gene; Lane 12: positive control for ermA gene of amplified 190-bp DNA (S. aureus T0131); Lane 13: negative control for ermA gene; Lanes 14 - 16: representative S. aureus nasal isolates negative for ermA gene; Lane 17: positive control for ermC gene of amplified 299-bp DNA (S. aureus 71193); Lane 18: negative control for ermC gene; Lanes 19 - 21: representative S. aureus nasal isolates negative for ermC gene.

| Animal Origin | Number of Isolates | Antibiotic Resistance Gene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaZ | mecA | tet (K, M) | erm (A, C) | ||

| Cattle | |||||

| 2 | + | - | - | - | |

| 2 | + | - | tetK | - | |

| - | - | - | - | - | |

| Sheep | |||||

| 8 | + | - | - | - | |

| 1 | + | + | tetK | - | |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Goat | |||||

| 6 | + | - | - | - | |

| 1 | + | - | tetM | - | |

| 4 | - | - | - | - | |

5. Discussion

The colonized S. aureus in the ruminant’s nasal cavities may be considered as a probable source of staphylococcal infections (4, 6, 29). In this study, a total of 26 S. aureus isolates were identified from 201 nasal swabs (12.9%) of ruminants including cattle, sheep and goats, by culture as well as species specific PCR. The frequency detected in the present study was, however, lower than the 43.7% reported for the same species in Saudi Arabia (23).

The present study indicated a relatively low prevalence of S. aureus nasal carriage (5.06%) in healthy cattle. This finding agrees with earlier reports from Norway and Sweden that evaluated potential sources of S. aureus in dairy herds (6, 30). However, this study showed a higher percentage of S. aureus nasal carriage in healthy sheep and goats. Such results are also similar to those previously reported for Norwegian dairy goats (6, 29) and dairy sheep (4, 6). Although the percentage of S. aureus nasal carriage in cattle was remarkably lower than those observed in sheep and goats, yet the reason for this is not clear. This variation could at least partly be due to differences in nasal physiology and self-care behaviors such as nose licking in cattle.

The high prevalence of S. aureus in the nasal cavity of small ruminants may be a predisposing factor for subsequent Intra-Mammary Infection (IMI), which needs additional comparative studies. In this regard, the nasal cavity of small ruminants has been proposed as the primary reservoir of S. aureus by some researchers (4, 6, 29).

Emergence of drug resistance organisms, especially MRSA, is a particular concern to both animal health and public health. There is now increasing evidence that MRSA can colonize and cause infection in companion animals as well as animals of the food chain (31). Furthermore, a few studies have reported a lower prevalence of MRSA in bovine and ovine mastitis (32, 33). Therefore, efforts should be made to characterize possible reservoirs in order to reduce the spread of MRSA. It has been shown that MRSA can colonize nares of ruminants (23). Similar to the results of other studies (34, 35), MRSA was not isolated from any of the cattle nasal swabs. However, this finding was inconsistent with the findings of Spohr et al. (36). In contrast to a previous study (37), none of the nasal isolates from goats carried the mecA gene. In the present study, only one out of 26 (3.84%) isolates harbored the mecA gene, which originated from sheep. This result is consistent with the findings of Gharsa et al. (7) where five of 163 healthy sheep (3%) carried MRSA in their nares. As, zoonotic transfer of MRSA has been reviewed between different animals and humans (38), more research should be done in this field in different parts of Iran to apply necessary management and health measures to prevent the spread of MRSA strains.

In the current study, a total of 20 out of 26 S. aureus nasal isolates possessed the blaZ gene. In similar studies conducted in Tunisia to assess S. aureus nasal carriage in sheep (7), cattle and goats (41), lower rates of blaZ-carrying S. aureus were identified. Differences in antibiotic regimens used in treating infections may explain these discrepancies among countries. Extensive use of β-lactam group of antibiotics for the treatment of animals in Iran (39) might explain the development of penicillin resistance among microbial strains isolated from farms animals in several reports from Iran (40, 41). These results indicate the need for effective transmission control of penicillin resistance in ruminants.

In Iran, tetracycline class of antibiotics remain as the first-line treatment of infections in livestock (42). Of the 26 isolates tested, four (15.4%) were positive for the presence of tet (K and M) genes, of which two isolates were obtained from cattle, while the other two isolates were from sheep and goats. Our results are in contrast with the results of Gharsa et al. (43), where no tetK and tetM genes were detected in cattle and goats nasal S. aureus isolates, yet similar to those reported for sheep isolates (7). It should be noted that the tet+ isolates harbored tetK more frequently than tetM, indicating that the tetracycline resistance mechanism is commonly mediated by the tetracycline efflux pump. This can be explained by their typical genetic locations, for example the tetK gene on small multicopy plasmids and tetM on conjugative transposon Tn916, which contribute to the spread of these determinants (44).

In this study, the ermA and ermC genes were not detected in any of the S. aureus isolates. This finding is consistent with previous studies on S. aureus isolates from nasal cavity of cattle and goats (34). However, in a study carried out by Gharsa et al. (7), 5.47% of the S. aureus isolates from nasal cavity of healthy sheep were positive for the ermC gene (7).

In general, the resistance gene patterns observed for S. aureus isolates from the nasal cavity of ruminants seems to reflect the patterns of drug therapy in these animal species. This was confirmed by veterinarians in the studied regions where the treatment plan of ruminant clinical infections is mainly based on using roughly 50% penicillin, 30% tetracycline, 20% other antibiotics including tylosin and gentamicin, and seldom use of macrolide antibiotics.

The presence of resistance genes among nasal isolates of S. aureus from ruminants in this study indicates that these species can serve as a cause of infection for humans. Transmission of S. aureus and its methicillin resistant variant between animals and humans has been frequently reported via direct contact (45) or indirect routes such as the environment and food chain (14, 46).

In conclusion, our findings show that the nares of healthy ruminants may represent a reservoir for antibiotic resistant S. aureus, underscoring the need for further extensive research to devise contextual control and prevention strategies. To our knowledge, this is the first survey in Iran examining the prevalence and resistance characteristics of S. aureus nasal isolates from ruminants.