1. Background

The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria constitutes a semipermeable barrier that slows the penetration of antibiotics. The permeability of this barrier is known to vary greatly among species, with the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa only 8% as permeable as that of Escherichia coli (1). This decreased permeability severely restricts the uptake of nutrients and other important compounds into the cell, which consequently must be imported into cells using a collection of water-filled protein channels called porins.

The P. aeruginosa family of porin proteins, defined based on their apparent sequence homology within the P. aeruginosa genome, plays an important physiological role in the transport of substances required for metabolism. However, these proteins also exhibit an affinity for certain hydrophilic antibiotics, such as β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracyclins, and some fluoroquinolones, allowing these compounds to transverse the otherwise insoluble outer bacterial membrane (2, 3). Deletion of one or more porin proteins has been shown to reduce the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to certain antibacterial agents (4).

The P. aeruginosa porin OprD is a substrate-specific porin that facilitates the diffusion of basic amino acids, small peptides, and carbapenems into the cell (5). OprD-mediated resistance occurs as a result of decreased transcriptional expression of oprD and/or loss of function mutations that disrupt protein activity. Specific mechanisms resulting in decreased transcriptional expression of oprD include (i) disruption of the oprD promoter, (ii) premature termination of oprD transcription, (iii) co-regulation with trace metal resistance mechanisms, (iv) salicylate-mediated reduction, and (v) decreased transcriptional expression via co-regulation with the multidrug efflux pump encoded by mexEF-oprN (6).

2. Objectives

In this study, we examined the level of oprD expression in P. aeruginosa clinical isolates to determine the contribution of OprD porins in carbapenem resistance. Clinical isolates were further examined using additional molecular methods to determine the degree of variability among isolates.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolates and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates were obtained from clinical samples sent to our laboratory routinely. Species identification was performed using conventional methods. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was carried out using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method (7). Isolates were divided into two groups according to their resistance status: multiple-drug resistant (MDR) and isolated carbapenem resistant (ICR).

3.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Testing

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of ceftazidime (CAZ), gentamicin (CN), piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP), ciprofloxacin (CIP), imipenem (IMP), and meropenem (MEM) were determined using the Vitek 2 system (bioMerieux, France). The Densi-Check 2 system (bioMérieux, France) was used to calibrate the turbidity of samples against the 0.5 McFarland standard. Susceptibility tests were performed on the Vitek 2 system using AST-N174 cards, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MIC values of ≥ 32 µg/mL for ceftazidime, ≥ 16 µg/mL for gentamicin, ≥ 128 µg/mL for piperacillin-tazobactam, ≥ 4 µg/mL for ciprofloxacin, ≥ 16 µg/mL for imipenem, and ≥ 16 µg/mL for meropenem were defined as resistance (7).

3.3. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Transcript levels of oprD were analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using a LightCycler instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). Total RNA was extracted using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) and converted into cDNA for qPCR using the Transcriptor High-fidelity cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). The quality and purity of the RNA obtained was evaluated spectrophotometrically (Maestrogen Nanodrop, USA). As a result of evaluation, required volume was calculated for 100 ng cDNA. Quantitative PCR was performed in capillary glass using the LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) with primers specific for oprD, and rpsL (Table 1).

Control cDNA was obtained from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1. Amplification of triplicate cDNA samples from each isolate was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation for 10 minutes at 95ºC, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95ºC for 20 seconds, annealing at 68ºC for 10 seconds, and elongation at 72ºC for 15 seconds. A final melting curve analysis was performed using a single read at 90ºC.

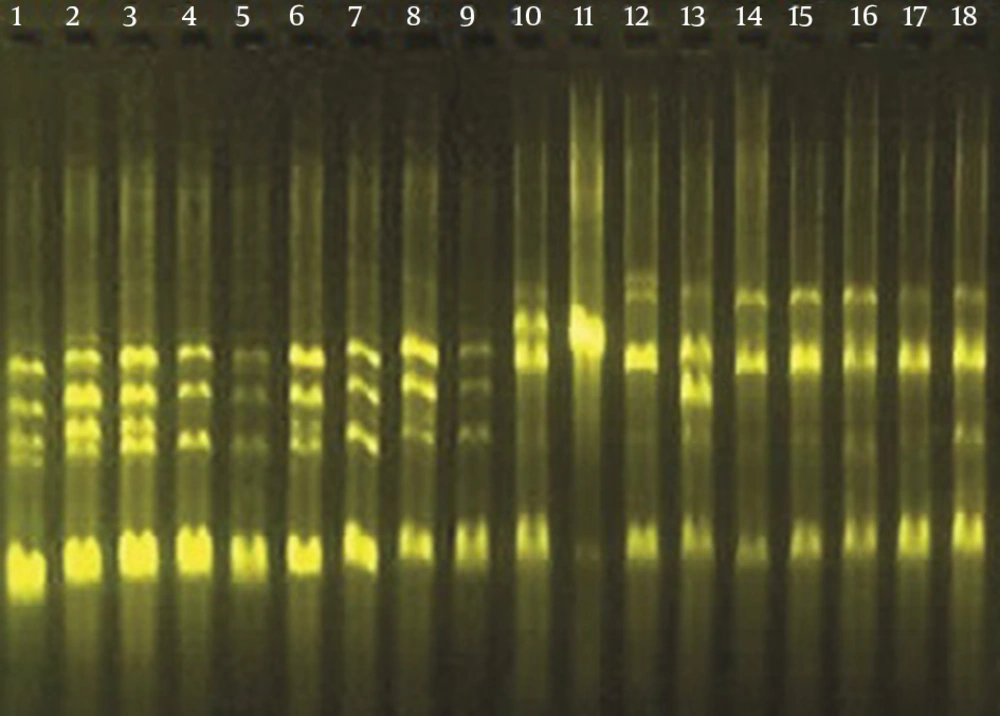

3.4. Arbitrarily Primed PCR (AP-PCR)

To evaluate the similarities among strains, arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) was performed using an M13 primer of sequence 5’-GAGGGTGGCGGTTCT-3’. PCR was carried out under the following conditions: 2 cycles of 94ºC for 5 minutes, 40ºC for 5 minutes, and 72ºC for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 94ºC for 1 minute, 40ºC for 1 minute, and 72ºC for 2 minutes. Amplification products were identified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and similarities among isolates were evaluated by comparison of the band profiles.

3.5. Evaluation of Gene Expression

Transcription data were analyzed using the LightCycler Relative Quantification software. Relative expression values (R) were determined using the ‘ΔΔCt’ method; the gene encoding ribosomal protein RpsL was used as a control (10). P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was used as a standard for normalization of relative mRNA levels. Reduced oprD expression was defined as transcription levels ≤ 70% of those of the PAO1 isolate (11).

Primer dimers and other artifacts were evaluated by melting curve analysis. To confirm that specific amplification had occurred, the melting curves of each amplicon were assessed and compared with Tm values obtained using PAO1 DNA as the template.

3.6. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS statistical software (version 17.0). Comparisons among groups were performed using a one-way ANOVA test.

4. Results

4.1. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Clinical isolates were divided into two groups based on their drug susceptibility profiles. MDR isolates were defined as those exhibiting resistance to ceftazidime (MIC ≥ 32), piperacillin (MIC ≥ 128), imipenem (MIC ≥ 16), and gentamicin (MIC ≥ 16) (12). All ICR isolates were resistant to imipenem, and an additional three isolates (33%) also exhibited resistance to meropenem. Antibiotic sensitivities and MIC data for each group are summarized in Table 2.

| Isolate | Groupa | AP-PCR Categoryb | MIC, mg/L Levels | Relative Gene Expressionc (oprD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ | TZP | CN | IPM | MEM | CIP | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | 8 | ≥ 4 | 0.165 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0.285 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 2 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0.005 |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 3 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0.002 |

| 8 | 1 | 3 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 3 | ≥ 64 | ≥ 128 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 4 | 0.001 |

| 10 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | 4 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.029 |

| 11 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | 8 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.034 |

| 12 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 32 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.04 |

| 13 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 8 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | 4 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.509 |

| 14 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 16 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.28 |

| 15 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 8 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | 4 | ≤ 0.25 | 2 |

| 16 | 2 | 6 | 2 | ≤ 4 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | ≤ 0.25 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.736 |

| 17 | 2 | 6 | 4 | ≤ 4 | ≤ 1 | ≥ 16 | 4 | ≤ 0.25 | 14.256 |

| 18 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 64 | 2 | ≥ 16 | ≥ 16 | ≤ 0.25 | 0.875 |

aGroup 1: Multiple drug resistant (MDR); Group 2: Isolated carbapenem resistant (ICR) P. aeruginosa isolates.

bAP-PCR category: Classification of P.aeruginosa isolates following AP-PCR analysis.

cRelative gene expression: expression levels were compared to fold PAO1.

4.2. Gene Expression

Relative mRNA expression levels of oprD were determined by qPCR. Decreased oprD expression was observed in 16 of 18 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates, with significant decreases detected in 13 isolates (72%). Within the MDR group, oprD expression was significantly decreased in all 9 isolates. oprD levels were decreased in 7 ICR isolates, with significant decreases found in 4 of these isolates. Detailed expression data for each group are shown in Table 2. Due to the consistently low expression seen in the MDR group, differences in mRNA expression between the groups were statistically significant (P = 0.001).

4.3. AP-PCR Analysis

The genetic similarity among isolates was determined using AP-PCR. Among the 18 clinical isolates tested, six distinct banding patterns were identified (Figure 1). Classifications of P. aeruginosa isolates based upon AP-PCR analysis are shown in Table 2.

5. Discussion

Pseudomonas aeruginosa represents a phenomenon of bacterial resistance, and most of the known antimicrobial resistance mechanisms are displayed in this species, and multiple resistance mechanisms may be expressed simultaneously within the same isolate (4). Due to the increase in multi-drug resistant P. aeruginosa infections, a greater emphasis has been placed on identifying genetic characteristics underlying bacterial resistance and the clinical implications of these mutations.

Outer membrane protein OprD is considered the preferred portal of entry for carbapenems and similar drugs such as imipenem and meropenem also enter the cell via OprD (3, 13, 14). Any loss of OprD expression from the outer membrane significantly decreases the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to carbapenems and has been shown to play a major role in the acquired resistance to imipenem and, to a lesser extent, meropenem (15). One study showed that OprD expression was decreased in the vast majority of 29 multi-drug resistant P. aeruginosa isolates (97%) and played a significant role in their carbapenem resistance (16).

Expression of oprD was decreased significantly in 13 of the 18 imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa clinical isolates examined in this study, including all 9 MDR isolates. The frequency of decreased oprD expression in MDR isolates was significantly higher than that of ICR isolates (P = 0.001), suggesting that oprD also plays an important role in the emergence of both carbapenem and non-carbapenem resistance.

The impact of OprD-mediated resistance on carbapenems can be quantified relative to its effect on the antibacterial potency of carbapenems (6). In a study evaluating isogenic wild-type and OprD-deficient mutant pairs, the loss of OprD decreased the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to meropenem 4- to 32-fold, compared with 4- to 16-fold for imipenem and 8- to 32-fold for doripenem (14). Zeng et al. (17) investigated relative gene expression in 29 carbapenem-resistant and ceftazidime- and cefepime-sensitive P. aeruginosa clinical isolates and found that the loss of oprD was directly related to carbapenem resistance. In another study, Fournier et al. (18) detected loss of oprD, as a result of mutations or gene disruptions, in 94 of 109 (86.2%) imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates.

In this study, oprD mRNA levels were decreased in 7 of 9 ICR isolates evaluated, even though significance was observed in only 4 of these isolates, in contrast with prior studies. Although our data are consistent with the basic mechanism of imipenem resistance mediated by diminished OprD protein levels in the outer membrane, the poor correlation between oprD mRNA expression and carbapenem resistance suggests involvement of additional resistance mechanisms in these isolates.

Impermeability was long thought to be the driver of intrinsic resistance in P. aeruginosa; however, resistance has since been found to involve a more complex interplay between impermeability and multi-drug efflux pumps (19). The interaction of efflux pumps with meropenem differs from that with imipenem. While it is believed that both meropenem and imipenem are able to enter the cell via the OprD pathway, only meropenem is a substrate of the MexAB-OprM efflux pump (19). Furthermore this mechanism plays a role in the emergence of resistance to fluoroquinolones and other β-lactams, increasing the likelihood of cross-resistance (20). However, despite this additional mechanism, meropenem resistance is less likely to be acquired than imipenem resistance (77 vs. 68% sensitivities for meropenem and imipenem, respectively), as it requires both the loss of oprD expression and upregulation of MexAB-OprM (6, 21). In our study, all 18 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates were resistant to imipenem, compared with only 12 isolates exhibiting meropenem resistance, consistent with previously published reports.

The relationship between OprD deficiency and imipenem resistance has been well established; however, cases of discordant OprD expression and carbapenem susceptibility, due to genetic versatility and multiple resistance mechanisms displayed in this pathogen, have been reported (6). El Amin et al. (15) identified four imipenem-susceptible isolates with significant reductions in oprD mRNA levels caused by severe oprD mutations that resulted in frame shifts or premature termination. Furthermore, they reported that the oprD mRNA levels did not always correlate with imipenem resistance, and differences in imipenem susceptibility could not be explained by oprD mutations or efflux pump genes (15). In our study, increased oprD levels were detected in 2 of the 18 imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa clinical isolates analyzed. Also we could not find any relation between genotype and resistance pattern in AP-PCR study. Further studies will be necessary to understand the mechanisms underlying this apparent discordance between oprD levels and imipenem resistance.

While OprD porin proteins play an important role in carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa, this resistance cannot be explained by OprD levels alone, and other important interactions may influence carbapenem susceptibility. Characterization of carbapenem resistance mechanisms could provide additional therapeutic targets or allow for alternative strategies to enhance the efficacy of carbapenems.