1. Background

Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) isolates cause dysentery in humans and are closely related to Shigella species with regard to their virulence, biochemical, genetic, and physiopathological properties (1). Bacillary dysentery is caused by four Shigella species or EIEC, and is characterized by abdominal cramps, fever, and stool that contains blood, mucus, and pus (2). Enteroinvasive E. coli may cause invasive inflammatory colitis and occasionally causes dysentery, but in most cases, EIEC isolates cause watery diarrhea indistinguishable from that due to other diarrheagenic E. coli strains (1, 3). Several virulence factors associated with Shigella and EIEC pathogenesis have been characterized. These microorganisms possess a large plasmid, pINV, which encodes several proteins involved in the invasion of host cells (4).

The invasion plasmid antigen H gene (ipaH) is present in multiple copies located on both chromosomes, and the plasmid is responsible for dissemination in epithelial cells (5). The invasion-associated locus (ial), which is carried on a large inv plasmid, is involved in cell penetration by Shigella and EIEC (5). Previous studies have suggested that two enterotoxins, Shigella enterotoxin 1 (ShET1) and Shigella enterotoxin 2 (ShET2), are associated with altered water and electrolyte transport in the small intestine (6). Shigella enterotoxin 1 (encoded by the set gene) is found in many isolates of S. flexneri serotype 2a and only rarely in other Shigella serotypes. ShET-2 (encoded by the sen gene) was originally discovered in EIEC isolates, but is found in many Shigella and EIEC isolates (6). Two plasmid-borne proteins, VirF and VirB (InvE) are involved in transcriptional regulation of the invasion genes (7).

The serine protease autotransporters of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATEs) comprise a diverse group of serine proteases, which are produced by members of the Enterobacteriaceae. Phylogenetically, the SPATE family can be divided into two classes. Class 1 SPATEs induce cytopathic effects in epithelial cell lines and include the plasmid-encoded toxin gene (pet) and its two homologs, Shigella IgA-like protease homologue gene (sigA) and secreted autotransporter toxin gene (sat) (8). Members of class 2 are non-toxic SPATEs, including a protein involved in intestinal colonization (Pic), and Shigella extracellular protein A (SepA), a toxin that contributes to intestinal inflammation. Both of these toxins were first reported in S. flexneri 2a (8).

Molecular typing methods are frequently applied for accessing genetic relatedness among bacterial pathogens for the purpose of epidemiological surveillance. Multilocus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) is a PCR-based method used for distinguishing between bacterial isolates (9, 10). Several studies have investigated VNTR loci variations to discriminate different E. coli and Shigella isolates (9-15).

2. Objectives

Despite various reports on the prevalence and distribution of virulence genes in Shigella spp. in different parts of the world, investigations into EIEC virulence genes are still rare worldwide, and we are not aware of any paper on this subject in Iran. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the distribution of numerous virulence genes and the genetic diversity of EIEC isolates.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection and EIEC Isolate Identification

A total of 620 stool samples were randomly collected from patients with diarrhea who presented at two major hospitals (Ayatollah Kashani and Afzalipour) in the city of Kerman from June 2013 to August 2014. The stools were immediately cultured on xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD) and MacConkey agar media. The lactose-positive colonies were then re-cultured with the standard biochemical method for detection of E. coli (11). Enteroinvasive E. coli isolate detection was conducted using a PCR assay with ipaH primer. The EIEC isolates were then stored in TSB broth containing 30% glycerol at a temperature of -70°C until further analysis.

3.2. PCR Assay for Virulence Factor Genes

All isolates were tested for the presence of nine virulence genes (Table 1). To identify the virulence genes, DNA was first extracted by the boiling method (10). Singleplex PCR was performed for the detection of the ial, set1A, sen, virF, and invE genes. master mix (Amplicon, Brighton, UK) was used, and the reaction was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplification was carried out in a thermocycler (Biometra-T gradient, Gottingen, Germany). The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 30 cycles including denaturation for 1 minute at 94°C, annealing for 1 minute (the primer annealing temperatures are listed in Table 1), and extension at 72°C for 45 seconds, with a single final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. For the SPATE genes, including sat, sigA, pic, and sepA, multiplex PCR was performed according to the method previously described (8), in a final volume of 20 µL containing 17 µL of master mix and 3 µL of DNA template. The cycling conditions comprised an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 30 cycles with denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing for 1 minute, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension step at 72°C for 7 minutes.

| Gene | Primer | Amplicon Size (bp) | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ipaH | GAAAACCCTCCTGGTCCATCAGG, GCCGGTCAGCCACCCTCTGAGAGTAC | 437 | 61 | (16) |

| ial | CTGGATGGTATGGTGAGG, GGAGGCCAACAATTATTTCC | 320 | 56 | (6) |

| set1A | TCACGCTACCATCAAAGA, TATCCCCCTTTGGTGGTA | 309 | 57 | (6) |

| sen | ATGTGCCTGCTATTATTTAT, CATAATAATAAGCGGTCAGC | 799 | 53 | (6) |

| virF | TCAGGCAATGAAACTTTGAC, TGGGCTTGATATTCCGATAAGTC | 618 | 58 | (6) |

| invE | CGATAGATGGCGAGAAATTATATCCCG, CGATCAAGAATCCCTAACAGAAGAATCAC | 766 | 59 | (6) |

| sat | TCAGAAGCTCAGCGAATCATTG, CCATTATCACCAGTAAAACGCACC | 930 | 58 | (8) |

| sigA | CCGACTTCTCACTTTCTCCCG, CCATCCAGCTGCATAGTGTTTG | 430 | 58 | (8) |

| pic | ACTGGATCTTAAGGCTCAGGAT, GACTTAATGTCACTGTTCAGCG | 572 | 58 | (8) |

| sepA | GCAGTGGAAATATGATGCGGC, TTGTTCAGATCGGAGAAGAACG | 794 | 58 | (8) |

3.3. VNTR Locus Selection and Amplification

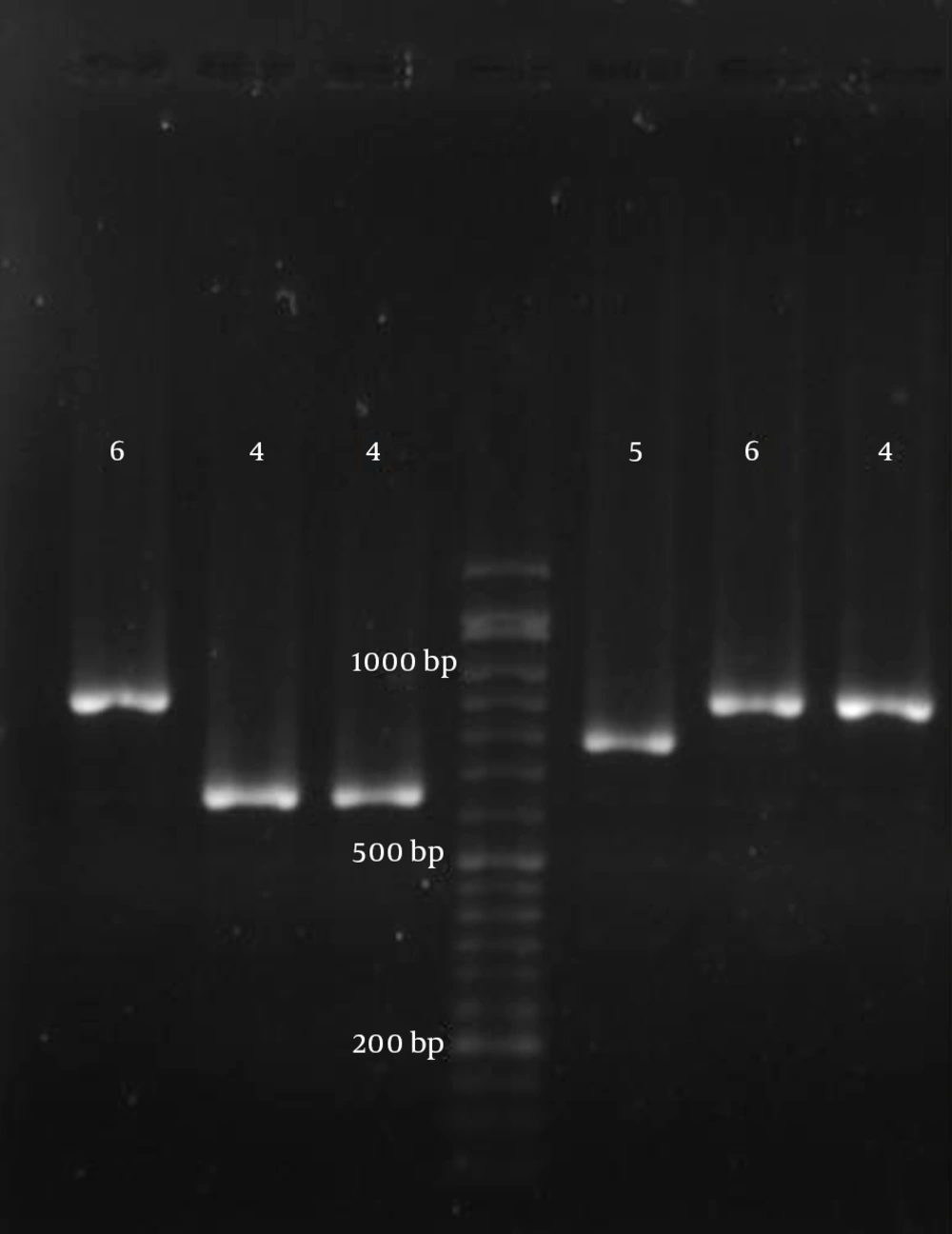

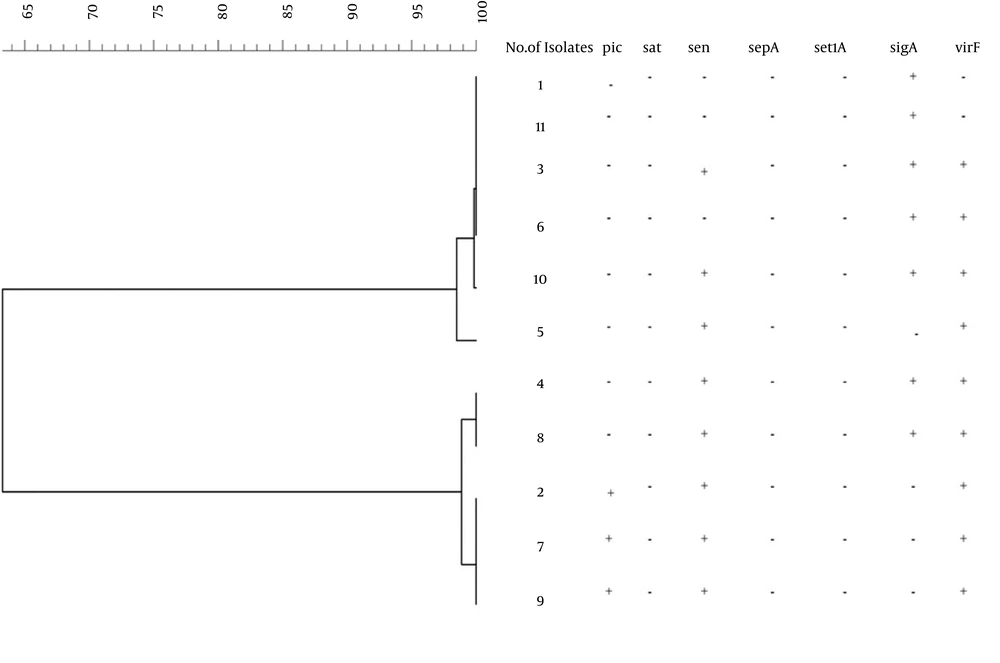

Various VNTR loci have been characterized in the genomes of E. coli and Shigella (12-14). From these, loci with appropriate repetitions and sufficiently long repeat sizes were selected for genetic typing of the EIEC isolates. Accordingly, seven different VNTR loci were selected, and PCR was performed according to the previously described method (14). The locus names, selected primers, and repeat sizes for each locus are presented in Table 2. After performing PCR, the size of each locus (amplicon size) was determined on 1.5% agarose gel, and the number of repeats was calculated (Figure 1). The results were entered into Microsoft excel 2010 software and analyzed with Bionumerics software (14). Any difference in one or more VNTR loci was considered to indicate a distinct type. A genotypic similarity of 90% was used as the cut-off value for clustering (17).

| Locus | Primer Sequence | Repeat Size (bp) | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms06 | F-AAACGGGAGAGCCGGTTATT, R-TGTTGGTACAACGGCTCCTG | 39 | 57 | (14) |

| ms07 | F:GTCAGTTCGCCCAGACACAG, R: CGGTGTCAGCAAATCCAGAG | 39 | 57 | (14) |

| ms09 | F:GTGCCATCGGGCAAAATTAG, R:CCGATAAGGGAGCAGGCTAGT | 179 | 57 | (14) |

| ms11 | F:GAAACAGGCCCAGGCTACAC, R:CTGGCGCTGGTTATGGGTAT | 96 | 57 | (14) |

| ms21 | F:GCTGATGGCGAAGGAGAAGA, R: GGGAGTATGCGGTCAAAAGC | 141 | 57 | (14) |

| ms23 | F:GCTCCGCTGATTGACTCCTT, R:CGGTTGCTCGACCACTAACA | 375 | 57 | (14) |

| ms32 | F:TGAGATTGCCGAAGTGTTGC; R:AACTGGCGGCGTTTATCAAG | 101 | 57 | (14) |

4. Results

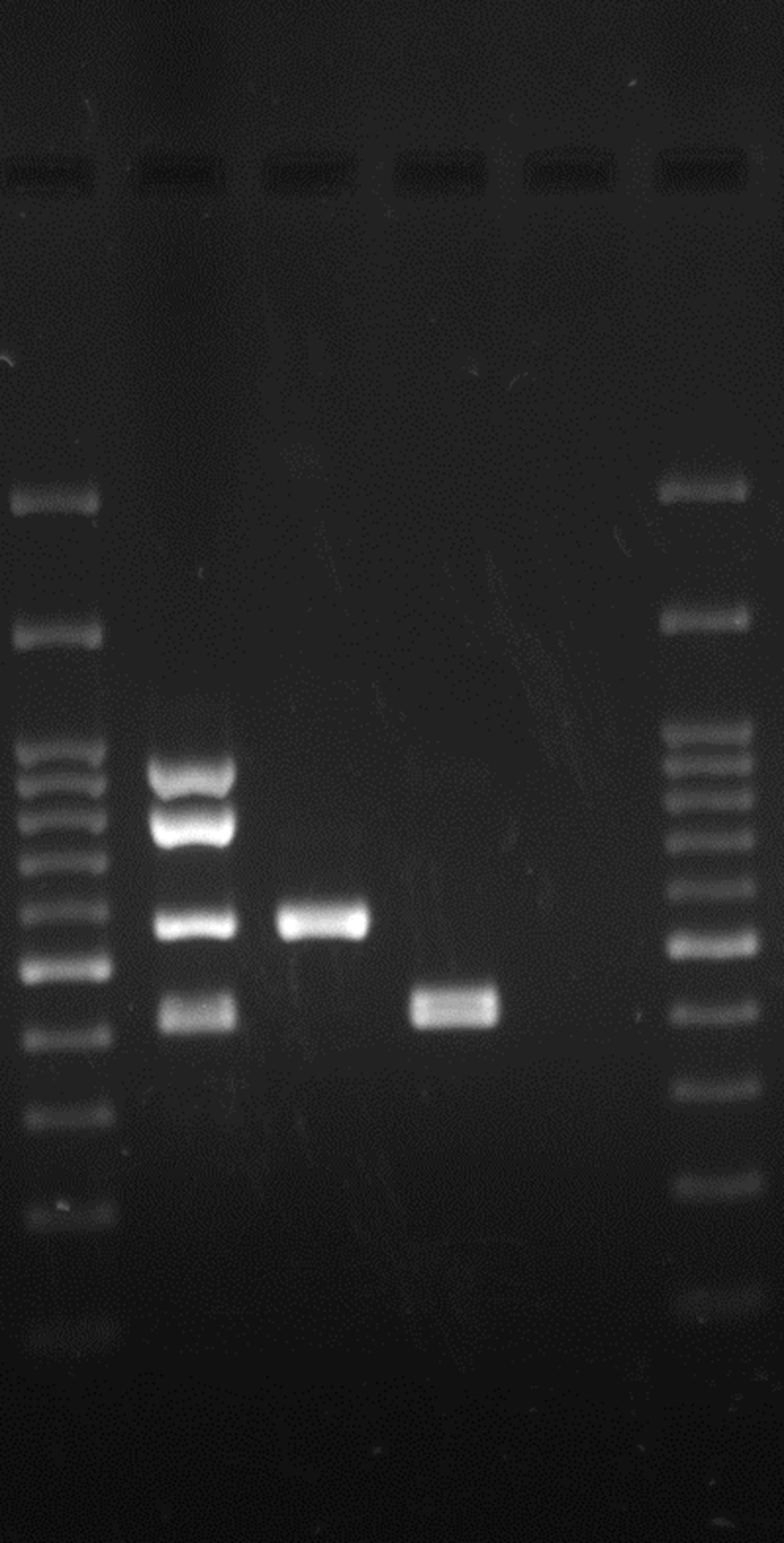

In the present study, eleven EIEC isolates were isolated from 620 stool samples from June 2013 to August 2014. The detection of the virulence genes from 11 EIEC isolates showed that all isolates were positive for ial, whereas 81.8% were positive for the invE and virF genes. The sen, sigA, and pic genes were detected in 72.7%, 63.6%, and 27.3% of the isolates, respectively (Figure 2). None of the isolates were positive for the sat, sepA, or set genes. Using MLVA, a total of 11 isolates were divided into five types. Analysis of the MLVA profiles using UPGMA showed that the EIEC isolates fell into two main clusters, using 90% similarity as the cut-off (Figure 3). In some cases, the patterns of virulence genes were not similar in isolates with the same MLVA type; however, isolates with similar MLVA patterns mostly had similar virulence patterns. For example, isolates 1 and 11, as well as isolates 2, 7, and 9, had identical patterns of virulence genes and similar MLVA patterns (Figure 3).

5. Discussion

Enteroinvasive E. coli isolates cause watery diarrhea and dysentery in humans, similar to that caused by Shigella spp. In the present study, 11 isolates of EIEC were obtained from 620 diarrhea samples, which indicates that EIEC is not endemic in Kerman. These results are consistent with the results of many studies around the world and in Iran (18-21), except for a limited number of reports (22, 23). EIEC isolates are similar to Shigella in terms of pathogenesis; however, very little research has been conducted to identify their virulence gene profiles. We studied the distribution of several virulence genes in EIEC isolates, which was mostly assessed only in Shigella spp. in previous studies. It has been reported that some of the Shigella isolates were negative for the ial gene because it is located on the inv plasmid, which is prone to loss or deletion (5, 24, 25). However, in the present study, all isolates were positive for the ial gene, and most were positive for the invE and virF genes.

This is in agreement with data obtained in previous studies on virulence gene distribution in Shigella spp. (6, 26). As expected, the set gene was not found in the EIEC isolates, while the sen gene was observed in 72.7%. The set gene has been found in S. flexneri (especially S. flexneri 2a), while sen has been identified in all Shigella spp. and also in EIEC isolates (5, 27). Pic and SigA toxins were found among our EIEC isolates. These SPATE toxins were also identified in a few previous studies on EIEC isolates (8, 28). These toxins, especially SigA, may be important for EIEC pathogenesis. In the current study, all isolates were negative for the Sat and SepA toxins. These results are consistent with those obtained by Taddei et al. (29) and Boisen et al. (8).

The genetic diversity of EIEC isolates has been studied only by a few researchers until now (4, 30, 31). We used the MLVA method for the typing of EIEC isolates. This method has several advantages, such as easy application, inexpensiveness, and repeatability (9), and it has been used for typing Shigella spp. and E. coli. In research by Liang et al. (13), MLVA showed a high level of discrimination compared to PFGE, and isolates with the same PFGE patterns were distinguished by the MLVA method (13). In research by Ranjbar et al. (10), similar to the present study, seven VNTR loci were used to distinguish 47 isolates of S. soneii. The S. sonnei isolates belonged to two clonal complexes and had little genetic diversity (10). In the current study, EIEC isolates belonged to two clonal complexes, which revealed that limited numbers of distinct clones cause the diarrhea related to EIEC isolates in Kerman. However, it may be possible to distinguish these closely related isolates with the MLVA method based on highly polymorphic VNTR loci. It should be noted that these methods require sequencing or microcapillary electrophoresis to determine the number of short repeats at the VNTR loci (12, 14). We selected VNTR loci that can successfully estimate the number of repetitive DNAs among the isolates based on agarose gel electrophoresis. Hence, our MLVA typing scheme would be a suitable tool for epidemiological studies in many laboratories with simple molecular biology equipment. In this study, isolates with the same MLVA type also had the same virulence gene patterns in most cases. However, in some cases, the virulence gene patterns of the isolates within an MLVA type were not similar. This might be a result of many virulence genes found on the large plasmid, which is prone to loss or deletions during growth under in vitro conditions.

In conclusion, it seems that EIEC is of little importance in the prevalence of diarrhea in Kerman. A number of virulence genes found in Shigella, such as sat, set, and sepA, were not found in EIEC. In our study, the incidence of EIEC was low, and a bigger sample size is needed to draw firm conclusions about the heterogeneity of EIEC isolates.