1. Background

Leishmaniasis as one of the emerging and neglected infectious diseases has been largely distributed in the world. Khuzestan province is situated on the border of Iran and Iraq, having a tropical climate with high prevalence rate of leishmaniasis in the five past years (1). Although, it is believed that three species of Leishmania parasites have been incriminated as the causative agents of human leishmaniasis in Iran, other mammals’ Leishmania species have been isolated and identified from sandflies, rodents, and humans (2).

Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) is an endemic disease in more than 80 countries in the world including Iran (3, 4). Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis is distributed in more than half of Iranian provinces and Khuzestan province in the southwest has been affected by the disease with new and unknown foci. The life cycle of Leishmania parasites in ZCL depends on some criteria such as sandfly species as vectors, wild rodent species as reservoir hosts, and the geographical locations as natural important foci of the disease (5, 6). Among different species of wild rodents, a few are identified as the main species of ZCL reservoir hosts in Iran. A number of rodent species are widespread; some of them in Asia and some others in smaller areas (7).

There are many important species of rodents from different ZCL regions in Iran such as Rhombomys opimus, Meriones libycus, M. persicus, Tatera indica, Nesokia indica, M. hurrianae, and Rattus norvegicus which have been reported as the main hosts of ZCL parasites. But there is no sufficiently precise and consistent evidence to confirm that all of the species are main reservoirs of ZCL in Iran and other regions (4, 8-20).

Currently, T. indica has drawn more attention not only as a principal ZCL reservoir but also due to our recent finding revealing that four subspecies of T. indica exist in Iran based on morphological and molecular characteristics. In spite of the expectation that two of which exist in Khuzestan province, only one subspecies was found (21).

2. Objectives

The objective of this investigation was to find the potential and/or prominent reservoir hosts of ZCL and define the role of T. indica in the transmission of Leishmania major in southwestern Iran. Another objective of this study was to explore (i) genetic variation, (ii) polymorphism, and (iii) genetic similarity as effective factors in maintaining equilibrium of mutation due to natural selection or genetic drift in the population of L. major isolated from sandfly species as vectors, wild rodent species as reservoirs and human at the border of Iran and Iraq (22).

3. Methods

3.1. Origin and Sampling of Leishmania From Reservoir Hosts

Rodents were collected from the active colonies of rodent burrows around the villages in the study area using 40 wooden and wire live traps in 2012 - 2014. Cucumbers and dates were used as baits for each location of ten villages in four districts of Khuzestan province. The areas’ altitude was 18 meters above the sea level (a.s.l) with geographical coordinates as: 31.3273°N; 48.6940°E; (Figure 1). The rodent traps were set up in active colonies in 6 cities (12 villages) of Khuzestan Province early in the morning. The traps were left for several days in each location. However, T. indica was captured only from 6 villages. The samples was collected from the colonies of rodents’ burrows located around the villages where ZCL was endemic using 50 wooden and wire live traps for each location.

The traps were checked and the baits were changed consecutively. Collected rodents were transferred to Pasteur Institute of Iran and maintained to be identified morphologically as well as molecularly.

3.2. DNA Extraction and Amplification of Leishmania Infection

The ears of each rodent were scratched and two impression smears were taken. Routine laboratory procedures and molecular methods of impression smears prepared from rodents’ ears were followed according to the Parvizi et al. (2008) protocol to detect Leishmania infection. Leishmania sampling from rodents, isolation of parasites, impression smears from each ear of rodents, light microscope observation, culturing in Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle (NNN), and inoculation in Balb/C from the captured rodents were followed by the methods of Mirzaei et al. (2011) (17).

Whole genomic DNA of T. indica was extracted using Genet Bio kit (Takapoo Zist), Phenol-Chloroform (CinnaGen Co. Tehran. Iran) and ISH Horovize methods based on Parvizi et al. (13). The DNA of all T. indica samples was extracted and the ITS-rDNA gene fragment of Leishmania parasites was amplified using PCR to find the precise species of Leishmania parasite causing leishmaniasis. The forward primer IR1 and the reverse primer IR2 were exerted for the first-stage of PCR; while for the second-stage of the nested PCR, the forward primer ITS1F and the reverse primer ITS2R4 were used (23, 24).

3.3. Sequences and Phylogenetic Analyses

The positive PCR products obtained from Leishmania parasites were directly sequenced, aligned, and edited to determine Leishmania species and haplotype variations in individual rodents using Sequencher 4.1.4TM for PC. Phylogenetic analysis was performed in MEGA 6 software. Maximum likelihood (ML) and neighbor-joining (NJ) were the two statistical methods to draw trees and determine the genetic relationship of Leishmania species with different original hosts using alternative Kimura 2-Parameter (K2P) models (25). The DnaSP5 software was used to indicate polymorphisms and haplotype diversities.

4. Results

4.1. Morphological and Molecular Identification

Among 121 rodents sampled from six districts around 12 villages and sites in Khuzestan province, Iran, in 2012 - 2014, 45 were identified as T. indica (Table 1 and Figure 1). All T. indica samples (20 female, 25 male) were identified first morphologically and then molecularly using Cyt b gene in the method of Parvizi et al. 2008 (13). Tatera indica was captured more in Behbahan than other locations; but no significant difference was found in Leishmania infections based on different locations. 41 live-captured T. indica samples were examined for Leishmania infections using both conventional and molecular methods; but only 4 dead captured T. indica were used to isolate and detect Leishmania parasites in molecular methods.

| Location | Habitat | T. indica | Age Groups | Season | Total (+ve) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Town | Leishmania (+ve) | 0 - 2 (+ve) | 2 - 4 (+ve) | > 4 (+ve) | Spring | Summer | Early Fall | Last Winter | |||||||

| Ahvaz | F (+ve) | M (+ve) | F (+ve) | M (+ve) | F (+ve) | M (+ve) | F (+ve) | M (+ve) | F (+ve) | M (+ve) | 10 (2) | ||||

| Jadeh Hamideyeha | 2 | 5 (1) LR | 1 | 2 | 4 (1) | 1 | 2 (1) | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Jadeh Abadana | 1 | 2 (1) LR | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Shushtar | Ghalehnoub | 0 | 1 (1) L | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (10) |

| Ramhormoz | Darkhouyina | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Shush | Sorkhehb | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Behbahan | Kharestana | 7 (1) LR | 10 (1) LR | 3 (2) | 5 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 21 (3) |

| Germezb | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ab Amirb | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Heyat Abadb | 1 (1) R | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Dezful | Gavmish Abadb | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 (1) |

| Bonyeh Abadb | 2 | 1 (1) R | 1 (1) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Seyed Nurb | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total No (+ve) | 20 (2) | 25 (5) | 9 (4) | 17 (2) | 19 (1) | 10 (0) | 8 (1) | 8 (1) | 13 (4) | 2 (1) | 3 (0) | 0 | 1 (0) | 45 (7) | |

| 45 (7) | 45 (7) | 45 (7) | 45 (7) | 45 (7) | 18 (1) | 18 (1) | 21 (5) | 21 (5) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |||

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; L, left ear; R, right ear; LR, right and left ear.

aRodent burrow, desert.

bRodent burrow, around villages.

4.2. Detection of Leishmania Infection Using Molecular Analyses

Seven out of 45 T. indica were found with Leishmania infection (Table 1). Live-captured T. indica were more infected with Leishmania (7 out of 41) than those captured dead (zero out of 4). No significant difference was found in Leishmania infection between left and right ears of T. indica. But concurrent Leishmania infection in both ears was more prevalent.

This is the first time to detect Leishmania parasites focusing only on T. indica in large scales of Khuzestan province. Leishmania major firmly was identified first time in 7 T. indica by amplifying 460 bp fragment of ITS1-5.8S rRNA -ITS2 gene, RFLP, sequences, aligning, and comparing our sequences with homologous ones from the GenBank database. In addition, this finding was important because Khuzestan province has up to 1609 kilometres shared border with Iraq. Twenty one sequences of ITS-rDNA of Leishmania parasites were analyzed for genetic polymorphism and genetic similarity. Leishmania were isolated from reservoir hosts of rodents, sandflies, and humans. 16 sequences of L. major, 4 sequences of L. tropica, and one sequence of L. infantum were employed for phylogenetic analysis trees reconstruction, and determination of the evolution of Leishmania parasites.

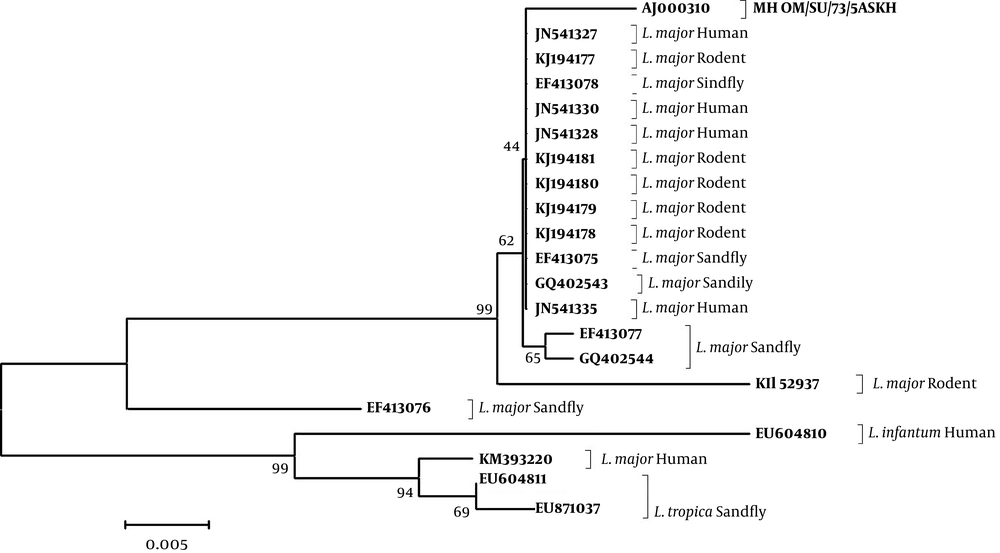

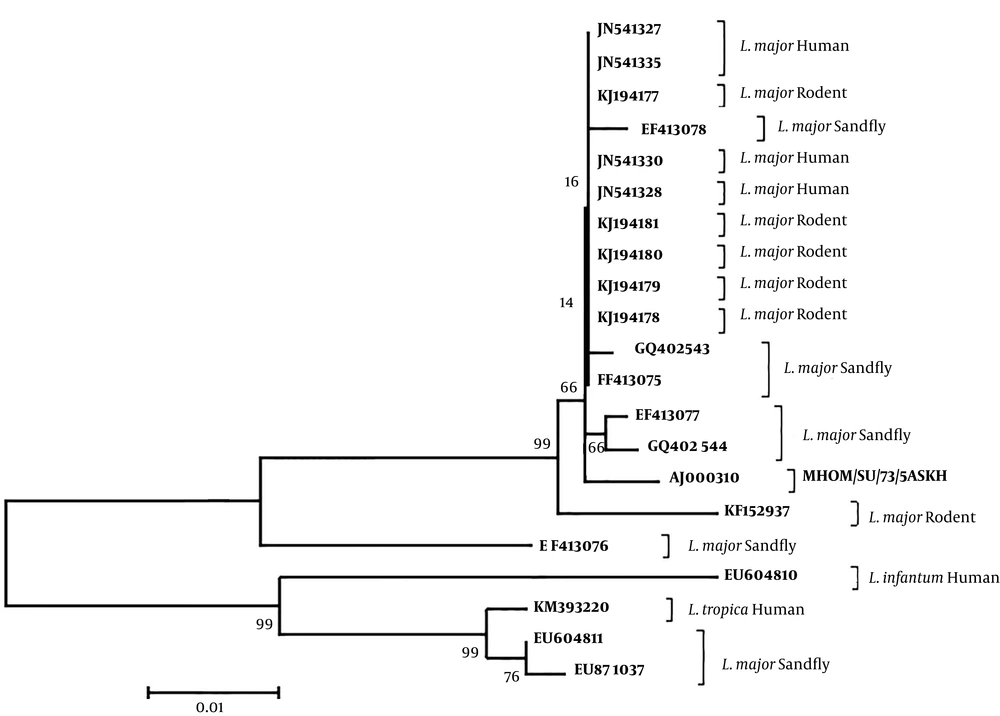

In terms of evolutionary relationships, molecular phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood and neighbor-joining methods revealed that taxa and two old world Leishmania species (L. major and L. tropica) had share common ancestors (Figures 2 and 3). In topology of trees, more variations were observed in L. major isolated from sandflies, followed by those from rodents and humans. L. tropica had more diversity than L. major and placed as out group (Table 2).

| Variables | Uninfected, (n= 38) | Infected, (n = 7) | OR (CI 95 %) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | ||||

| 0 - 2 | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 1 | 0.105 |

| 2 - 4 | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0.27 (0.026 - 2.916) | 0.284 |

| > 4 | 18 (94.7) | 1 (5.3) | 0.052 (0.003 - 0.81) | 0.035 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 17 (85.0) | 3 (15.0) | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 21 (84.0) | 4 (16.0) | 1.05 (0.090 - 12.228) | 0.969 |

| Season | ||||

| Spring | 17 (94.4) | 1 (5.6) | 1 | 0.480 |

| Summer | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | 7.1 (0.43 - 111.15) | 0.170 |

| Late fall | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 20.35 (0.22 - 1861.4) | 0.191 |

| Early winter | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Habitat | ||||

| RBAVb | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 1 | 1 |

| RBDc | 23 (82.1) | 5 (17.9) | 2.96 (0.33 - 26.1) | 0.328 |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

bRodent burrow around village.

cRodent burrow desert.

5. Discussion

Research on rodents as leishmaniasis reservoirs has revealed a diverse array of transmission cycles where epidemic cutaneous disease caused by L. major occurs near colonies of reservoir gerbil rodents in Asia including Khuzestan province on the border of Iran and Iraq (19). Rodents are not always well distinguished in literature; although distinguishing closely-related members of T. indica species is complex, it is important for transmission cycle and epidemiological aspects (13, 26). This is crucial to separate reservoirs that are biomedically important from the rodent species that are competent reservoirs but without reservoir capacity to cause much ZCL disease (7, 24). The ecological associations with infected reservoir hosts or humans, and the descriptive eco-epidemiology could suggest a potential reservoir role. Modeling of transmission cycling associations is required to identify the reservoirs that are a real public health priority (6, 27).

Most ZCL infections are diagnosed clinically and microscopically in patients; but in reservoir hosts, a combination of molecular, biochemical, and serological tests can demonstrate significant numbers of Leishmania infections in endemic areas of ZCL foci (28, 29). The incidence of ZCL associated with the transmission of L. major by rodents has declined in many foci where living standards have been improved (4). Only one report on Leishmania infection in one T. indica has been presented in a very small area of Khuzestan province named Roffaye, although it is not clear how authors confirmed L. major without sequencing and aliment and molecular analyses (19). Rhombomys opimus as the main reservoir host of ZCL has been trapped frequently in many areas of Iran while they were more with Leishmania infections; despite expecting the same situation in the case of T. indica as the second main reservoir host of ZCL in south of Iran, the minority of T. indica were found with Leishmania infection in the conducted investigations (17, 30, 31).

Despite low Leishmania infection in T. indica, the prevalence of human disease and infections is relatively high in some districts of Khuzestan province, so that these districts appear to have a transmission cycle typical of the ZCL, while T. indica were incriminated as the reservoir hosts of L. major (1, 10, 17, 20). Using cross tab, chi-square, and adjusted logistic regression statistical tests, some epidemiological factors such as age, gender, season, and habitat were analyzed to compare any epidemiological factor affecting Leishmania infection in T. indica. No significant factor was found to change the situation of disease; however, small changes in some factors were shown (Table 2). Statistical analyses showed the first age group of T. indica had significantly high Leishmania infection. This may be due to that younger T. indica search for food and show more activities around the rodent borrows and this can increase the chance for biting by sandflies.

Using ITS-rDNA gene and two statistical methods (NJ and ML), a few old world Leishmania species were identified in Iran and elsewhere under similar conditions (22, 32-34).

The number of pairwise differences among sequences was compared with the expected number of segregating sites in Leishmania species and using Tajima’s D index analysis, a negative evolution process was found; also, the number of observed mutations was lower than the number of expecting mutations. Majority of mutations were not informative but unique. The gape in alignments of ITS-rDNA gene increased with the number of different haplotypes while by ignoring or removing the gap, the number of haplotypes decreased (Table 3).

| Host | Parasite Sp. | No. Seq | No Nucleotide2 | S (%) | K | Per Seqb | πc | Per Siteb | Tajima’s D | Singleton Variable | Parsimony Variable | H | Hd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Gap | Without Gap | With Gap | Without Gap | ||||||||||||

| Rodent | L. major | 6 | 373 (336) | 5 (1.488) | 1.66 | 2.18 | 0.0049 | 0.006 | -1.33 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.33 |

| Sandfly | L. major | 6 | 373 (333) | 15 (4.504) | 5.2 | 6.56 | 0.015 | 0.019 | -1.22 | 15 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0.93 |

| L. tropica | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Human | L. major | 4 | 373 (337) | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 1 | 0.83 | 0 |

| L. tropica | 3 | 373 (332) | 17 (5.120) | 11.33 | 11.33 | 0.034 | 0.034 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| L.infantum | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Total | All | 21 | 373 (306) | 33 (10.784) | 7.6 | 9.17 | 0.025 | 0.029 | -0.64 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 10 | 0.97 | 0.68 |

Abbreviations: S, segregation of variable nucleotide sites; K, average number of pairwise nucleotide difference between pairs of sequences; H, No. of haplotype; Hd, haplotype diversity.

aNumber of sequence used in this study.

bThe amount of genetic variation.

cNucleotide diversity, Tajima’s D: the D test statistic proposed by Tajima, (35).

Using the maximum likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model, a tree with the highest log likelihood (-838.0810) was constructed. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained by applying the neighbor-joining method to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the maximum composite likelihood (MCL) approach. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (5 categories (+G, parameter = 0.2030)). The tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 21 nucleotide sequences. There were a total of 373 positions in the final dataset (Figure 2). Using the neighbor-joining method, the optimal tree with the sum of branch length of 0.13416000 was drawn. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown next to the branches. The tree was drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Kimura 2-parameter method in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The rate variation among sites was modeled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter = 1). The analysis involved 21 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 306 positions in the final dataset (Table 3, Figures 2 and 3). Phylogenetic trees for L. major are supported on their specific clades and L. tropica on own clades.

The current report established that T. indica is not the only reservoir host of ZCL circulating in Khuzestan province. Our investigation raises the possibility that the role of some rodents or other mammals in the incidence of ZCL might be due to some changes in the transmission rate of L. major. Phylogenetic analysis of ITS-rDNA gene is recommended for firm identification and separation of Leishmania species.