1. Background

Enterococci have changed from commensal intestine organisms in human beings to a significant cause of infection (1). These bacteria are important causes of nosocomial infections, such as urinary tract infections, bacteremia, and endocarditis (2). Recently, enterococci have become considerably resistant to a broad range of antimicrobial agents, particularly glycopeptides, β-lactam, and aminoglycosides (3). Due to inappropriate use of antibiotics in nosocomial infections, the resistance rate is increasing (4). Enterococcus faecalis and E. faecium are two common species isolated from nosocomial infections. The prevalence of antibiotic resistance among E. faecium is higher than in E. faecalis (4). Enterococci are either intrinsically resistant to antibiotics or acquire the resistance genes (5, 6). The resistance is due to inadequate transfer of antibiotics across the cytoplasmic membranes of bacteria. Antibiotics that are effective on the cell wall of the bacteria, such as β-lactam or vancomycin, have a synergistic effect in the treatment of enterococci infections (7). The presence of high-level gentamicin resistant (HLGR) species is globally important due to their multi-resistant nature (8). Unfortunately, enterococci with high-level aminoglycoside-resistance (HLAR) (MIC > 500 µg/mL) do not seem to be sensitive to this synergistic effect, making treatment more difficult (9). HLAR in enterococci is due to aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs). The most common genes coding AME are aac(6’)-aph(2”) and aph(3)-IIIa (10). AMEs eliminate the synergism effect of aminoglycosides when combined with a cell-wall-active agent. Aac(6’)aph(2”) is the most common gene causing HLGR in enterococci, and aph(3)-IIIa is common in high-level kanamycin and streptomycin resistance (11). An increase in the prevalence of HLGR has been observed in European, Asian, and South American countries. The prevalence of HLGR isolates recently soared by 10 times, to above 50% in blood culture isolates from E. faecium, which seems to be a rising trend (12).

2. Objectives

Imam Reza hospital in Kermanshah is a referral center in the western part of Iran, with different wards and specialties. The recognition of antimicrobial resistance patterns, particularly in nosocomial infections, can serve as a guideline for selecting suitable treatments and effective antibiotics. The present study was designed to identify the prevalence of, and to compare, the aac(6’)-aph(2”) and aph(3)-IIIa genes and their antimicrobial resistance patterns among E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates from patients at Imam Reza hospital in 2011 - 2012.

3. Patients and Methods

The study was performed on 138 isolates of Enterococcus obtained from patients hospitalized in different wards of Imam Reza hospital during 2011 - 2012. The Enterococcus isolates were identified at the species level based on standard biochemical methods. The antibiotic susceptibility patterns of the isolates were determined by the disk diffusion method according to clinical and laboratory standard institute (CLSI) guidelines (13). The antimicrobial disks used were kanamycin, teicoplanin, streptomycin, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, and ampicillin (MAST, UK). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the aminoglycosides gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, and amikacin were measured by the microbroth dilution method, with antibiotic dilutions ranging from 16 to 8192 µg/mL.

3.1. PCR for Detection of AME Genes

In this study, PCR was employed to detect two AME genes: aac(6’)-aph(2”) and aph(3”)-IIIa, which have been reported to be considerably distributed among enterococci. The DNA of the isolates was extracted using the boiling method (14). PCR reactions were performed in 15 µL volumes with 1.5 mM of MgCl2, 200 µM of each dNTP, 0.5 µM of each primer, 1X PCR buffer, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase, and 100 ng of the enterococcal chromosomal DNA. After heating at 95°C for 5 min, amplification was performed over 30 cycles: 95°C for 30 s, 30 s at the specific annealing temperature for each primer, and 72°C for 30 second, followed by 72°C for 5 minutes (15). The annealing temperature was 50°C for 30 second for the genes. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis at 90 V for 60 minutes on 1% agarose gel. Finally, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide, photographed, and analyzed with the gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Singapore). The sequence of the primers and the size of PCR products are shown in Table 1.

4. Results

Among 138 isolates obtained from patients in different wards, 33 (24.1%) were E. faecium and 63 (46%) were E. faecalis. Enterococcus isolates were identified to the species level based on biochemical tests, and PCR was done in order to investigate HLGR genes.

4.1. Antibiotic Susceptibility Test (Antibiogram)

The antibiotic susceptibility patterns of the isolates were determined by the disk diffusion method according to CLSI guidelines. The rates of enterococcal resistance to antibiotics were: ciprofloxacin 20 (20.8%), teicoplanin 7 (7.3%), imipenem 9 (9.4%), tobramycin 11 (11.4%), kanamycin 77 (80.2%), erythromycin 88 (91.7%), and ampicillin 82 (85.4%). Erythromycin and ampicillin showed the highest level of resistance, while the lowest level was related to teicoplanin.

4.2. Determining MIC50 and MIC90 for Aminoglycosides

Among the aminoglycosides, the highest level of MIC50 was related to kanamycin and gentamicin. For MIC90, kanamycin, gentamicin, and streptomycin were noteworthy. Eighty-nine percent of isolates were diagnosed as HLGR.

4.3. Prevalence of Resistance Genes to Aminoglycosides

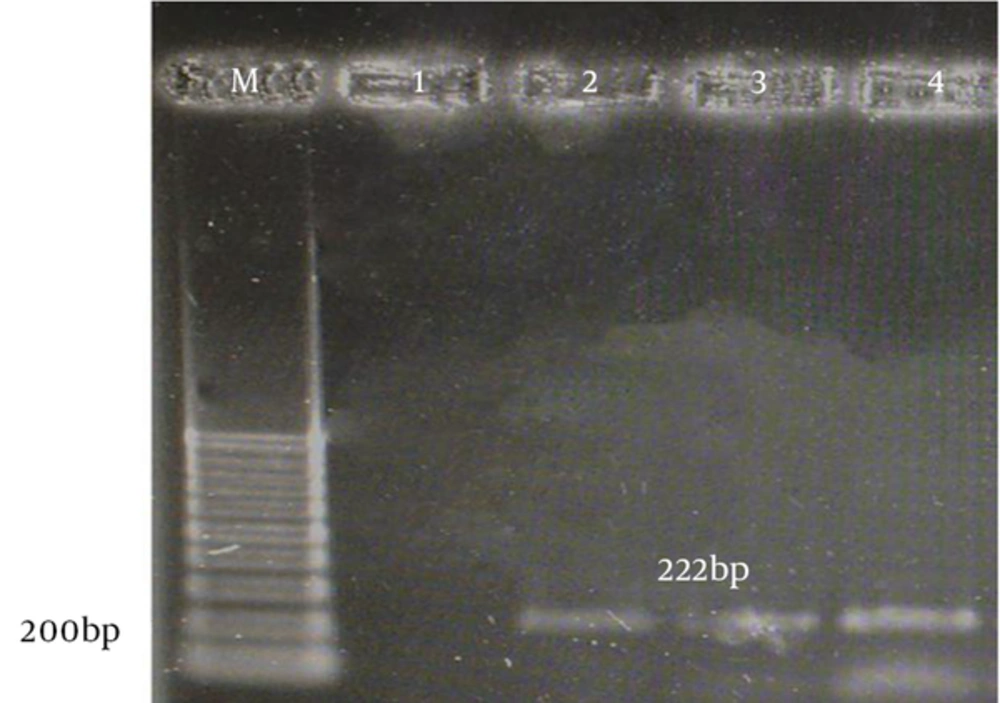

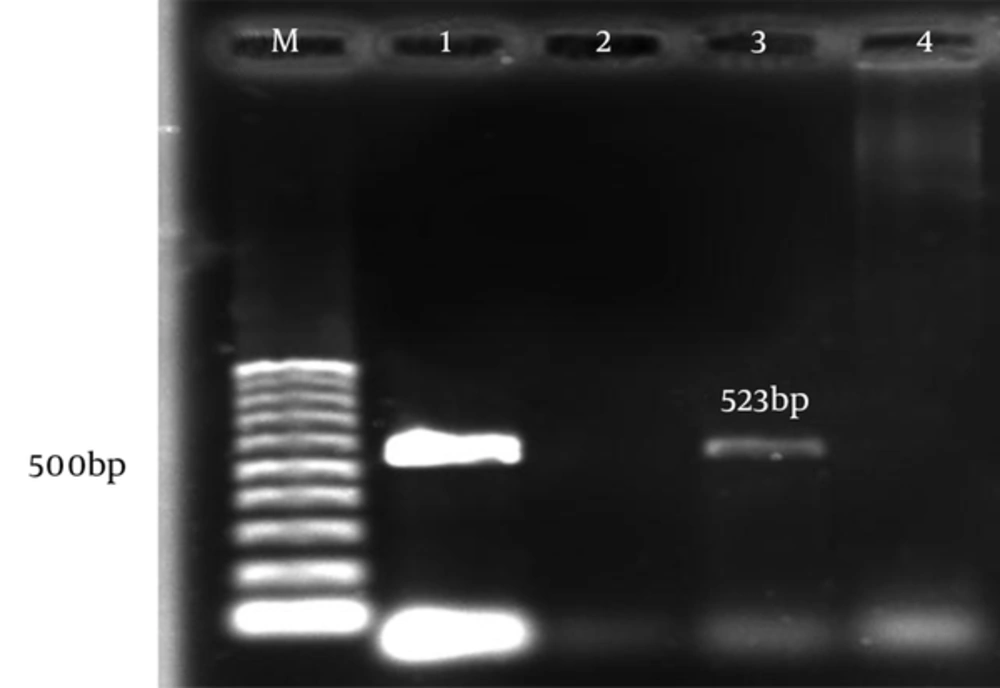

The aac(6)-le-aph(2)la and aph(3)-llla genes were determined by PCR according to specific primers. Figure 1 and 2 show the gel electrophoresis results for these genes. Based on the PCR method, the aac(6)-le-aph(2)la and aph(3)-llla genes were found in 64 (61.6%) and 22 (19.6%) of the isolates, respectively. Table 2 shows the frequency of genotypes resistant to aminoglycosides according to enterococcal species.

| Gene | E. faecalis | E. faecium |

|---|---|---|

| aac(6)-le-aph(2)la | 43 (67.2) | 21 (32.8) |

| aph(3)-llla | 5 (22.7) | 17 (77.3) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

In recent years, enterococci have become important causes of nosocomial infections throughout the world, and it has been proven that enterococcal strains are the main cause of 82% of urinary tract infections in Iran (18). Aminoglycosides are frequently used to treat enterococcal infections, which can lead to the spread of aminoglycoside-resistant isolates in Iranian hospitals (19). The increasing number of enterococcal species resistant to antibiotics are currently a challenge with regard to treatment. In the present study, enterococcal isolates obtained from Imam Reza hospital, a referral hospital in Kermanshah, were studied to determine the prevalence of E. faecalis and E. faecium among hospitalized patients. The patterns of antimicrobial resistance of the isolates and two important HLGR genes, aac(6’)-le-aph(2")-la and aph(3), were also investigated. Among the different species of enterococci that are currently recognized, E. faecalis is responsible for 85% - 95% of enterococcal infections, while 5% - 10% of infections are caused by E. faecium (20).

In a similar study in Iran, it has been reported that E. faecalis and E. faecium strains have the highest incidence, 80% - 85% and 15% - 20%, respectively (21, 22). In contrast, European studies have reported that E. faecium was the most prevalent isolate, followed by E. hirae and E. faecalis (23). Aleksandrowicz (24) showed that E. faecalis was the most frequent enterococcal species in all samples, more than 70%, followed by E. faecium (20.4%). In our study, 65.6% of isolates were identified as E. faecalis and 34.4% were E. faecium. Enterococci have become increasingly resistant to a broad range of antimicrobial agents, particularly glycopeptides, ß-lactams, and aminoglycosides (25). Among the resistance mechanisms, HLAR is widely reported, while glycopeptide-resistant or β-lactam-resistant enterococci are prevalent mostly in western countries (26). HLAR leads to the loss of synergy between cell wall synthesis-inhibiting antibiotics, such as penicillins or glycopeptides, which allows aminoglycosides to penetrate through the impermeable bacterial cell wall (27).

In the present study, most isolates were sensitive to imipenem (91.9%), and the rates of resistance to erythromycin, ampicillin, and kanamycin were 63.2%, 58.8%, and 55.1%, respectively. A Turkish study by Akhter et al. (28) showed that imipenem was considered to have the highest level of sensitivity. Compared to our study, Imanifooladi et al. (22) showed that most isolates of enterococci were resistant to erythromycin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin. With regard to aminoglycoside resistance, 8.1% of isolates were resistant to tobramycin and 55.1% to kanamycin, while 89% of all isolates were HLGR. In comparison to our study, Emaneini’s survey in Tehran showed 52% of isolates to be HLGR, and Hasani’s 2012 study in Tbariz reported that 60.45% of isolates were HLGR with MICs of ≥ 512 μg/mL (29, 30). Our study showed that HLGR isolates are more popular in Kermanshah. According to the literature, HLGR is more common in Iran, and it is predicted that gentamicin will have no place in the treatment of enterococcal infections. Isolates that express high-level resistance to amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and streptomycin were investigated for the presence of genes encoding the aac(6’)-Ie-aph (2”)Ia and aph(3’)-IIIa enzymes.

The HLAR in enterococci is usually coded by the aac(6’)-aph(2”) gene encoding the aac(6’)-aph(2”) enzyme (31). The PCR results for the isolates demonstrated that 68.3% of E. faecalis and 36.4% of E. faecium isolates contain the aac(6’)-aph(2”) gene. A similar study in Japan showed the prevalence of this gene to be 40.1% among E. faecalis and 12.9% among E. faecium samples (32). In Denmark, 32% of isolates were defined as E. faecalis, and all of them contained this gene (12). According to our study, the prevalence of aph(3) was 23.8% and 21.2% for E. faecalis and E. faecium, respectively. It can be concluded that the most prevalent gene leading to aminoglycoside resistance is aac(6)-aph(2), and in the current study, the presence of this gene was more common than aph(3) in both E. faecalis and E. faecium. The large differences among hospitals in both the use of antimicrobials and the prevalence of resistance indicate the potential for further improvement of antibiotic policies, and possibly for hospital infection-control in order to maintain low resistance levels (1). Physicians are obliged to use antibiotics appropriately and to comply with infection-control policies in an effort to prevent further spread of these resistant organisms.