1. Background

Leishmaniasis is a zoonotic disease caused by a protozoan parasite, called Leishmania, belonging to Kinetoplastida protozoa. Depending on the type of lesion in the human body, leishmaniasis is classified into cutaneous, visceral, and mucocutaneous types and is mainly transmitted by various species of sandflies (1, 2). It is estimated that 1 to 1.5 million cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis occur annually, and over 370 million people are at risk of this infection (3). As reported previously, more than 90% of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases are from Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Pakistan, Palestine, and Yemen (4). Common antimony compounds, including meglumine antimonate (Glucantime) and sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam), are considered as the first-line drugs for treating leishmaniasis. These medications prevent the production of adenosine triphosphate through affecting parasitic enzymes, especially disruption of phosphokinase (5).

In recent years, increased resistance to pentavalent antimonials has led to the introduction of new anti-leishmanial compounds, such as miltefosine, amphotericin B, ketoconazole, and paromomycin (6). Most of the medications employed to treat leishmaniasis have one or more limitations. They are mostly uneconomical and have problems like administration route, toxicity, and increased parasite resistance to these medications, which is the most important issue. Currently, increased resistance to antimony compounds is alarming and a major challenge to successful treatment (7, 8). Hence, a need to develop effective, low-cost, and orally administered anti-Leishmania compounds with low toxicity is felt more than ever. In many developing countries, people pay special attention to traditional medicines and use them to meet their health needs. Given that herbal medicines often do not have any side effects and are available and cheap, the importance of using native herbs in each region is highlighted (9-12).

Artemisia absinthium is one of the oldest medicinal plants in the world whose name has been mentioned in most of the ancient scientists’ works. Artemisia absinthium is a perennial herbaceous plant of the family Asteraceae (Compositae) and has many active and anti-cancer ingredients, including glycoside, tannin, thujone, potassium nitrate, organic acids, Artacebin, Thujylalcohol, tincture, isovaleric acid, camphene, chamazulene, p-Coumaric acid, beta-Carotene, salicylic acid, ascorbic acid, chlorogenic acid, protocatechuic acid, vanillic acid, isoquercitrin, and rutin. In addition, there is a bitter substance in the leaves of this plant named absinthin, which its essence contains Cadinene and phellandrene and has worm-killing property. This is the reason that this plant is also called worm wood.

Absinthin has also anti-parasitic, appetizing, digestive, and reinforcing properties (13-15). Extensive body of evidence has indicated that the induction of macrophages defense mechanisms against Leishmania is closely related to IFN-γ and nitric oxide secretion. Some of the herbal extracts have immune-modulatory properties and increase secretion of nitric oxide.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine the anti-Leishmania and immune-modulatory effects of A. absinthium extract on the growth of Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER) in mouse peritoneal macrophages.

3. Methods

3.1. Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.UMSU.REC.1393.102).

3.2. Preparation of Hydroalcoholic Extract of A. absinthium

Artemisia absinthium samples were collected from northwest of Iran, and their herbarium codes were obtained (9526). The percolation method was used for extraction. In short, after drying and grinding, the plant was soaked in 70% alcohol for 48 hours. The obtained liquid was dried at 37°C after passing through a filter. An amount of 800 mg/mL stock solution was prepared from the obtained extract and kept in a refrigerator. Based on a previous study, different concentrations of 6.5, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 mg/mL were prepared (16).

3.3. Cultivation of Leishmania major

The standard strain of L. major promastigotes (MRHO/IR/75/ER) was cultured in RPMI1640 medium containing 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 24°C ± 1°C. Promastigotes in stationary phase were counted and used for the study.

3.4. Evaluation of the Anti-Leishmania Effects Using the MTT and Trypan Blue Tests

The parasitic suspension containing 106 promastigotes was added to sterile ELISA microplate wells and incubated for 24 hours. Afterwards, 100 µL of different dilutions of the extract was added to the wells and incubated for 24, 48, and 72 hours. Microplates were centrifuged at 201 RCF (18 g) for 5 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and 20 μL of the working 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-Yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution was added to each well (17-22). Four hours after centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and 100 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added. After 15 minutes, optical densities (ODs) were read using an ELISA reader (Stat fax 2100, USA) at the wavelength of 492 nm with an additional 630 nm filter. Trypan blue test was also performed to assess the anti-Leishmania effect of the extract. Finally, promastigotes were counted, and calculations were conducted according to the Neubauer chamber formula using the Trypan blue test.

3.5. Extraction of Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages and Exposure to Leishmania Promastigotes

To extract macrophages, 1.5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 3% thioglycolate was injected into the peritoneum of the mice. After two days, the mice were anesthetized with ether and killed. Under sterile conditions, 8 mL of PBS was injected intraperitoneally to release more macrophages. The macrophages were washed three times with cold sterile RPMI1640 in a refrigerated centrifuge (Centurion 5413 IT 249R, West Sussex, UK) at 700 RCF (18 g) for 5 minutes. The extracted cells were counted, and the macrophages were diluted five times and counted again four times; the average of live macrophages counted was 17.75. The number of cells was calculated according to the formula as follows: the number of viable cells × 104 × 5 = cell/mL culture. This cell suspension was transferred to cell culture flasks and incubated in a humid condition in 5% CO2 at 37°C for three hours. Then, flask supernatant was evacuated and discarded. Ten promastigotes per macrophage cell were added to the wells.

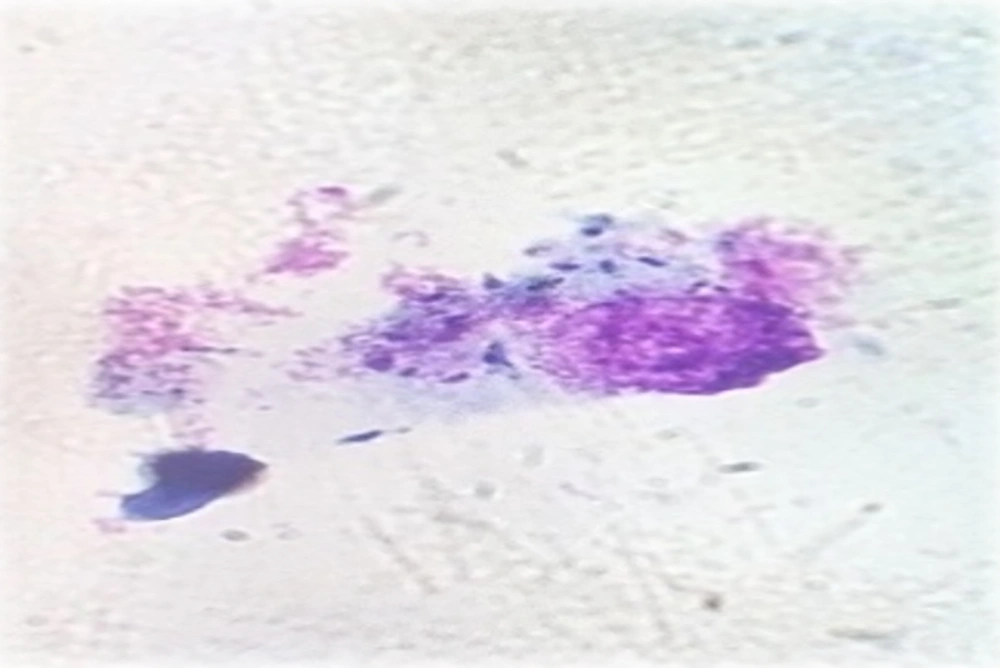

The flasks were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 hours with adequate humidity to provide an opportunity for infection of the macrophages with L. major. After 24 hours, the slides were prepared and stained with Giemsa and examined under a light microscope at magnification × 40. A total of 100 infected and non-infected macrophages were counted, and the percentage of infected macrophages was determined. Leishmania-infected macrophages were placed in the macrophage culture wells, and 100 µL of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract (12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL) was added. Also, 100 µL of Glucantime (positive control) with the concentration of 100 mg/mL (23, 24) and 100 µL of the contents of the flask without extract and medication (negative control) were added to the control wells. Cell culture plates were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 72 hours with optimal humidity, and the slides were prepared from wells and stained with Giemsa stain daily. Finally, the number of infected macrophages and the mean number of amastigotes were determined.

3.6. iNOs Measurement of Leishmania-Infected Macrophages

To measure specific iNOs from infected macrophages, cells were incubated with different concentrations of A. absinthium extract following 24, 48, and 72 hours of exposure. The supernatant was removed, and an ELISA test was performed to measure the enzyme level (iNOS) according to the kit’s instruction.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

OD of parasitic samples was entered in the Excel software, and the IC50 value was calculated using linear regression curve. The OD obtained was directly associated with the number of living and active cells.

4. Results

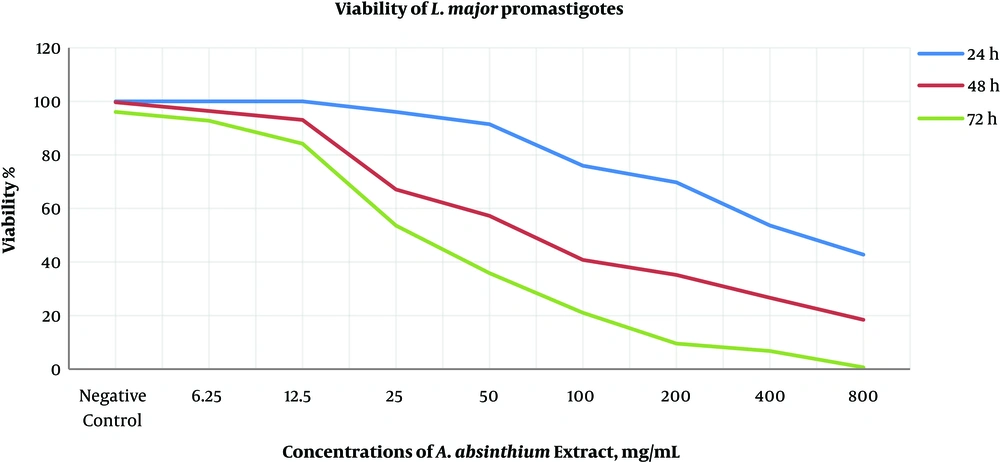

This study examined the anti-leishmanial effects of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract on the growth of promastigotes and amastigotes using the MTT assay, Trypan blue test, and Giemsa staining. First, the effect of different concentrations (6.5, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 mg/mL) of the extract on promastigotes was examined, and then the IC50 value was determined (Table 1). In the next step, after preparing peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice and infecting macrophages with stationary phase promastigotes and counting amastigotes and determining the percentage of infected macrophages, the effect of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract (12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL) and controls on amastigotes and infected macrophages was evaluated. By examining the effect of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract on promastigotes after 24 hours of exposure, we found that concentrations of 400 and 800 mg/mL had more than 50% leishmaniacidal effect, and concentrations less than 50 mg/mL had almost no effect (Figure 1). After 48 hours of exposure, the IC50 value of A. absinthium extract was calculated as 50 mg/mL. Leishmanicidal effect of concentrations greater than 200 mg/mL ranged from 65% to 80%. After 72 hours of incubation, concentrations of 12.5 mg/mL and lower were ineffective, and concentrations equal to or greater than 50 mg/mL had 50% to 98% leishmaniacidal effect. This effect increased depending on exposure time and concentration (Figure 2).

| Incubation Time (H) | Concentration (mg/mL) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Negative) | 6.25 | 12.5 | 25 | 50 | 100a | 200a | 400a | 800a | |

| 24 | 76 ± 4.33 | 76 ± 0.90 | 76 ± 2.22 | 73 ± 3.48 | 69.5 ± 7.02 | 57.75 ± 4.11 | 53 ± 1.73 | 40.75 ± 2.07 | 32.5 ± 2.87 |

| 48 | 75.75 ± 4.23 | 73.25 ± 4.21 | 70.75 ± 1.71 | 51 ± 1.82a | 43.5 ± 2.5a | 30.75 ± 3.25 | 26.75 ± 0.6 | 20.25 ± 0.85 | 14 ± 1.49 |

| 72 | 73 ± 1.82 | 70.25 ± 2.02 | 64 ± 5.16 | 40.7 ± 2.8a | 27.25 ± 4.41a | 16 ± 1.7 | 7.25 ± 1 | 5 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 0.5 |

Average Number of Live Promastigotes After Exposure to Different Concentrations of A. absinthium Extract After 24, 48, and 72 Hours Incubation

The effect of A. Absinthium extract in different concentrations and at various temperatures on L. major promastigotes. (Average percentage of infected macrophages). After 72 hours of incubation, concentrations of 12.5 mg/mL and lower were ineffective and concentrations equal to or greater than 50 mg/ml had 50% to 98% leishmaniacidal effect. This effect was increased depending on the time and concentration.

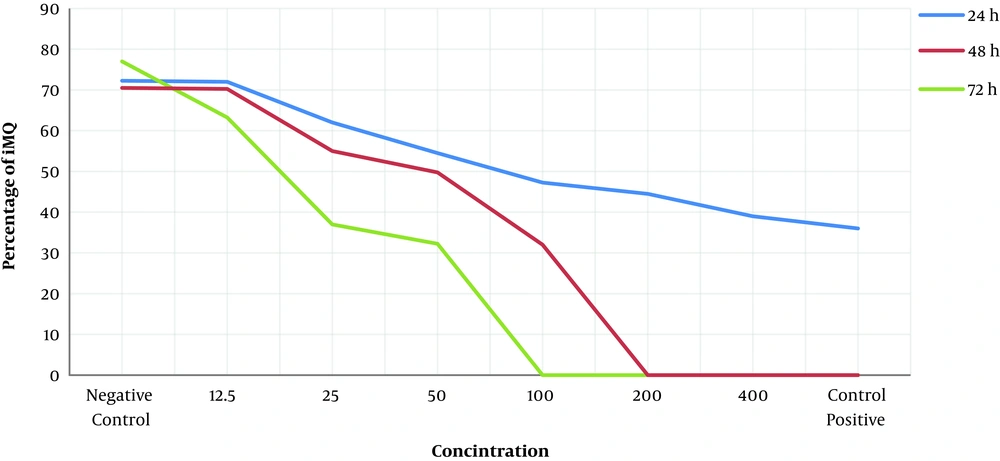

After 24, 48, and 72 hours of incubation, the effect of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract on the growth of amastigotes was examined using Giemsa staining in 5% CO2 with optimal moisture at 37°C (Figure 3). According to the IC50 value of A. absinthium extract at the promastigote stage, very high and very low concentrations of A. absinthium extract were not used. After 24 hours of incubation under appropriate conditions, concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL had 43.5%, 54%, and 58.5% leishmaniacidal effects on amastigotes, respectively. However, other concentrations had less effects. After 48 hours of incubation, concentrations of 400 and 200 mg/mL had 100% leishmaniacidal effects on amastigotes. The IC50 value of A. absinthium extract was calculated as 50 mg/mL. After 72 hours of incubation, concentrations greater than 100 mg/mL had 100% leishmaniacidal effect, and concentrations of 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/mL had 36%, 65%, and 72% leishmaniacidal effects on amastigotes, respectively.

After 24 and 48 hours of incubation under appropriate conditions, the high concentrations of A. absinthium extract and positive control (Glucantime) had no effects on non-infected macrophages. A gradual reduction in iNOs level and the lowest level of iNOs were evident at the 100 mg/mL concentration of A. absinthium after 24 and 48 hours of incubation, and the lowest level of iNOs affected by various concentrations of A. absinthium occurred at the 100 mg/mL concentration. Hence, after 24 and 48 hours of incubation, the optimal concentration of A. absinthium was 100 mg/mL, and after 72 hours of incubation, 50 mg/mL and 100 mg/mL produced the lowest levels of iNOs, respectively (Table 2).

5. Discussion

According to the World Health Organization, more than 80% of the world’s population (about 5 billion people) still use herbal medicines to treat diseases (25-29). Almost 50% of medications produced in the world are of plant origin, which are extracted directly from plants or synthesized based on herbal compounds. Plants are a potential source for anti-protozoan medications. Biological activity of plant extracts originates from compounds belonging to several chemical groups, including alkaloids, flavonoids, and steroids, which give anti-bacterial, anti-parasitic, and anti-oxidant properties to the plant (30, 31).

By examining the effect of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract on promastigotes using Trypan blue staining after 24 hours of exposure, we found that the concentrations of 800 and 400 mg/mL have more than 50% leishmaniacidal effects, and concentrations lower than 50 mg/mL had less effects. After 48 hours of exposure, the IC50 value of A. absinthium extract was 56 mg/mL and the leishmaniacidal effect of concentrations greater than 200 mg/mL ranged from 65% to 80%. After 72 hours of incubation, the concentrations of 12.5 and 6.25 mg/mL were ineffective and those equal to or greater than 50 mg/mL had 50% to 98% leishmaniacidal effects. After 48 hours, the bactericidal effects of Glucantime at the concentrations of 25 and 50 mg/mL were 36% and 54%, respectively, and other concentrations had 75% and 100% leishmaniacidal effects. This effect increased depending on exposure time and concentration such that after 72 hours, the concentration of 25 mg/mL showed to have 83% and the other three concentrations had 100% leishmaniacidal effects.

An in vitro study similar to our study was conducted on mice to examine the effect of two native plants namely Artemisia sieberi besser and Scrophularia striata boiss on the growth of L. major. The results showed that 20% and 25% concentrations of Artemisia extract completely destroyed promastigotes on the first day, highlighting the effectiveness of Artemisia in inhibiting the parasite’s growth; this result is consistent with the in vitro phase of our study (32). Another investigation has assessed the synergistic effects of mixed Achillea millefolium, A. absinthium, and walnut leaf extracts on L. major in vitro and found that plant extracts increase the immobility of parasites, which was directly associated with exposure time. That in vitro investigation, the same as the present study, confirmed the effectiveness of A. absinthium extract in inhibiting the growth of L. major (33, 34). Another study evaluated the anti-leishmanial effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Calendula officinalis on L. major promastigotes in vitro. This extract killed all parasites at a concentration of 500 µg/mL, and lower concentrations showed dose-dependent anti-Leishmania activity, and after 24 hours, the IC50 values in the alcoholic and aqueous extracts were obtained at 170 µg/mL and 215 µg/mL concentrations, respectively (35).

In concordance to our results, Azizi et al. have investigated the in vitro efficacy of ethanolic extract of A. absinthium against L. major using MTT and flow cytometry assays. They found some contrasting relationships between A. absinthium concentrations and the viability of L. major promastigotes. It could be concluded that it is likely that one or more chemical constituents within the herbal extract of A. absinthium at high concentrations control cell division and affect the relevant activity within the only one giant mitochondrion in this flagellate parasite (36). In our study, after 24, 48, and 72 hours of incubation, the effect of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract on the growth of amastigotes was examined using Giemsa staining at 37°C in 5% CO2 with optimal moisture.

According to the IC50 value of A. absinthium extract at the promastigote stage, very high and very low concentrations of extract were not used. Given that 100 mg/mL of Glucantime had the highest effect on promastigotes, this concentration was used as the positive control in the assessment of the effect of A. absinthium on amastigotes. In our study, the repeated measures analysis of variance showed a significant reduction in the number of L. major parasites in terms of time (P < 0.05), indicating the effect of Artemisia extract on reducing the number of promastigotes. Artemisia absinthium extract had also different effects at different times (P < 0.05). Further, 800 and 400 mg/mL concentrations of Artemisia absinthium extract had the same effects on the growth of L. major at different times (P > 0.05). The number of Leishmania parasites in the control medium (without medication or extract) was equal to the number of basic parasites, and it was not significant. There was also no significant reduction in Leishmania parasite growth (P > 0.05).

The results of our study showed the impact of different concentrations of the extract on the iNOs secretion from amastigote-infected macrophages. Our results also indicated that in early exposure and the innate immune system functioning, this medicinal plant activated and reinforced macrophages. In addition, the secretion of iNOs from amastigotes-infected macrophages reduced after 24-hour exposure to various concentrations of A. absinthium extract so that iNOs reached its lowest level at the concentration of 100 mg/mL. Besides, iNOs secretion decreased at 72, 48, and 24 hours, respectively, which displays an immune shift to Th1 and cellular immunity and more production of classic macrophages in the absence of iNOs. The classic macrophage (M1) can be created when this enzyme is reduced, which shifts immunity to cellular immunity (37, 38).

5.1. Conclusions

In sum, the effect of different concentrations of A. absinthium extract on the growth of L. major showed that all concentrations of this extract are able to reduce this parasite’s growth. According to our results, a significant decline was observed at different concentrations, and no significant reduction was observed in the growth of Leishmania parasites.