1. Background

Infections with Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Mycoplasma hominis are the most common bacterial sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) worldwide. These microorganisms are thought to induce a wide spectrum of urogenital tract diseases in men and women, including non-gonococcal urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic prostatitis, tubal obstruction, and unexplained chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. In addition, some studies have presented C. trachomatis, U. urealyticum, and M. hominis as the causal agents of human infertility (1, 2). The role of these microorganisms in male infertility is still unclear. A number of studies have specifically looked at the relationship between these infections and semen quality while some other studies have shown that these bacterial agents do not affect the parameters of semen and thus, the available evidence is conflicting (1, 3, 4).

Reducing the quality of sperm may also be associated with apoptosis of sperm cells. Apoptosis is a programmed cellular death based on a genetic mechanism. Apoptosis markers described in somatic cells were distinguished in human semen. Chlamydia trachomatis can lead to the variation of semen parameters and the induction of apoptosis in semen, thus weakening the ability of sperm to fertilize. Some studies have tried to establish a relationship between chlamydial infection and apoptosis; however, most studies have shown that the apoptosis-inducing mechanism is unclear (4, 5).

2. Objectives

This case-control study was conducted to determine the prevalence of C. trachomatis, M. hominis, and U. urealyticum in infertile couples. In addition, we established for the first time the effect of C. trachomatis infections on semen parameters and apoptosis markers among infertile men in Iran, using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay and Western blot.

3. Methods

3.1. Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1395.161.).

3.2. Study Patients and Sampling

In this study, a total number of 50 infertile couples who were admitted to the Infertility Treatment Center, Ahvaz, Iran, from August 2016 to March 2017 were selected. Infertility was defined as a failure to conceive after at least one year of unprotected intercourse. Because genital mycoplasmas are also considered as a commensal (3), we used a control group to determine the prevalence of genital mycoplasmas and compare it with our patients’ group. The sample size was determined by the statistical consultant according to the prevalence of C. trachomatis, M. hominis, and U. urealyticum in different papers. A total number of 50 semen samples and 50 endocervical swabs from infertile couples, and 50 endocervical swabs and 50 semen samples from fertile women and men were included in this study.

The mean age of patients and healthy groups was 31.4 years (range 20 - 40). The inclusion criteria for patients included the lack of antibiotic therapy for one week before sampling and sexual abstention for at least 48 hours before the tests. Infertility was tested by an andrologist and gynecologist, and people who did not have the necessary conditions were excluded from the study. People attending for checkups comprised the control group and the inclusion criteria were the lack of having a history of infertility and recent antibiotic therapy. No re-sampling was performed for this study and the remaining laboratory samples were used. We did not receive personal information from the patients’ files and only was a questionnaire completed for consented patients.Endocervical specimens were collected using sterile Dacron swabs and transported to the laboratory in 5 mL phosphate buffer solution (PBS). Semen samples were collected by masturbation into a sterile container after 4 - 5 days of abstinence. Then, the semen specimens were liquefied for 30 min at 37°C in an incubator before being analyzed. Semen analysis was performed according to the WHO criteria to determine the following variables: pH, volume, motility, sperm concentration, and normal morphology (6).

3.3. Bacteria Isolation

The culture method was performed only for M. hominis and U. urealyticum. The specimens were inoculated into the transport medium, pleuropneumonia-like organisms (PPLO broth) (Difco, USA), supplemented with inactivated horse serum (5%) and penicillin G (Sigma, US) 5000 u/L, and transported to the laboratory. One mL of each sample was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 minutes and 200 μL of the specimens were placed in PBS and stored at -70°C until DNA extraction for PCR assay. The inoculated transport medium was filtrated through 0.45-μL pore size disposable filters and the filtrates were inoculated into PPLO broth (Difco, USA) supplemented with horse serum (20%), 10 mL yeast extract (Merck, Germany) 25%, 2 mL phenol red (Sigma, US) 0.02%, penicillin G (Sigma, US) 5000 u/L, and 20 mL urea (Sigma, US) 10% (specific for U. urealyticum) or 20 mL arginine (Sigma, US) 10% (specific for M. hominis).

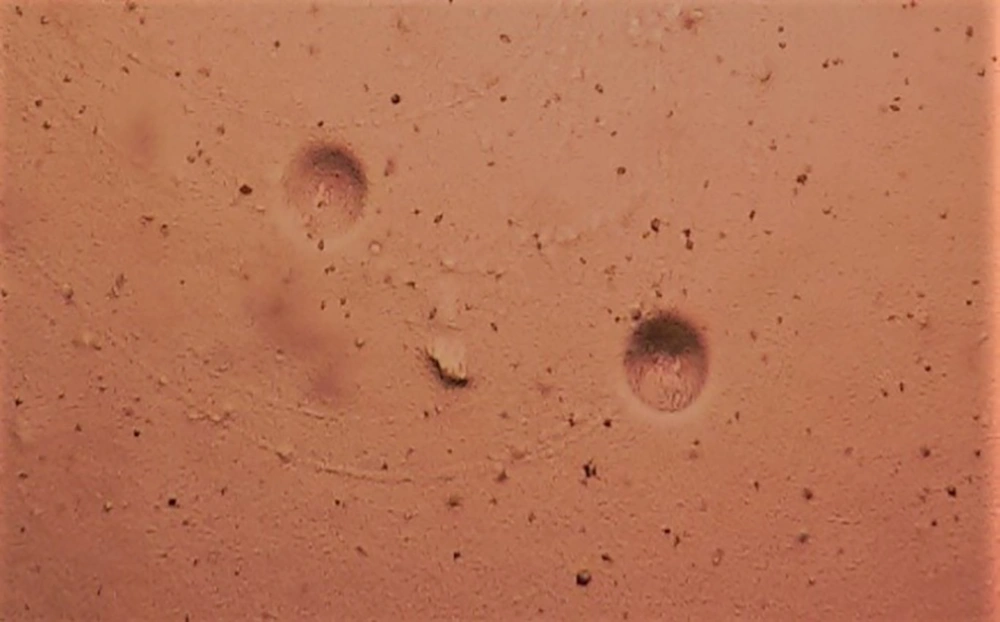

The pH was adjusted to 6.0 for the PPLO broth containing urea and to 7.5 for the PPLO broth containing L-arginine. The media were incubated in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48 - 72 hours. If growth proceeded, a color change was observed. After pH changed, 0.5 mL of the medium was transferred into the PPLO agar (PPLO broth components added to 1% agar). The plates were incubated at 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48 - 72 hours. The plates were stored for five to seven days at 37°C and M. hominis and U. urealyticum colonies were examined using a microscope (40X). Mycoplasma hominis colonies were similar to fried eggs in a solid medium (Figure 1), whereas U. urealyticum colonies were tiny and looked like mulberries. If no colonies were observed within 5 - 10 days, it was considered a negative culture.

3.4. Molecular Methods

Genomic DNA extraction was performed using high pure PCR template preparation kits (Roche Diagnosis, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The sequences of primers for C. trachomatis, U. urealyticum, and M. hominis are listed in Table 1. The PCR was performed according to the same method described in a previous study (7). To confirm the presence of Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma by PCR, sequencing was performed and it will be recorded soon in GeneBank. In addition, the genomic DNA from C. trachomatis (ATCC VR-885) was used as the positive control.

| Microorganism | Primer Sequences | Length, bp | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| U. urealyticum | Urease gene | 167 | (7) |

| F: 5’ GAG ATA ATG ATT ATA TGT CAG GAT CA 3’ | |||

| R: 5’ GAT CCA ACT TGG ATA GGA CGG 3’ | |||

| M. hominis | 16S rRNA | 334 | (8) |

| F: 5’ CAA TGG CTA ATG CCG GAT ACG C 3’ | |||

| R: 5’ GGT ACC GTC AGT CTG CAA T 3’ | |||

| C. trachomatis | MOMP gene | 180 | (9) |

| F: 5’ GCC GCT TTG AGT TCT GCT TCC 3’ | |||

| R: 5’ GTC GAA AAC AAA GTC ACC ATA GTA 3’ |

3.5. TUNEL Assay

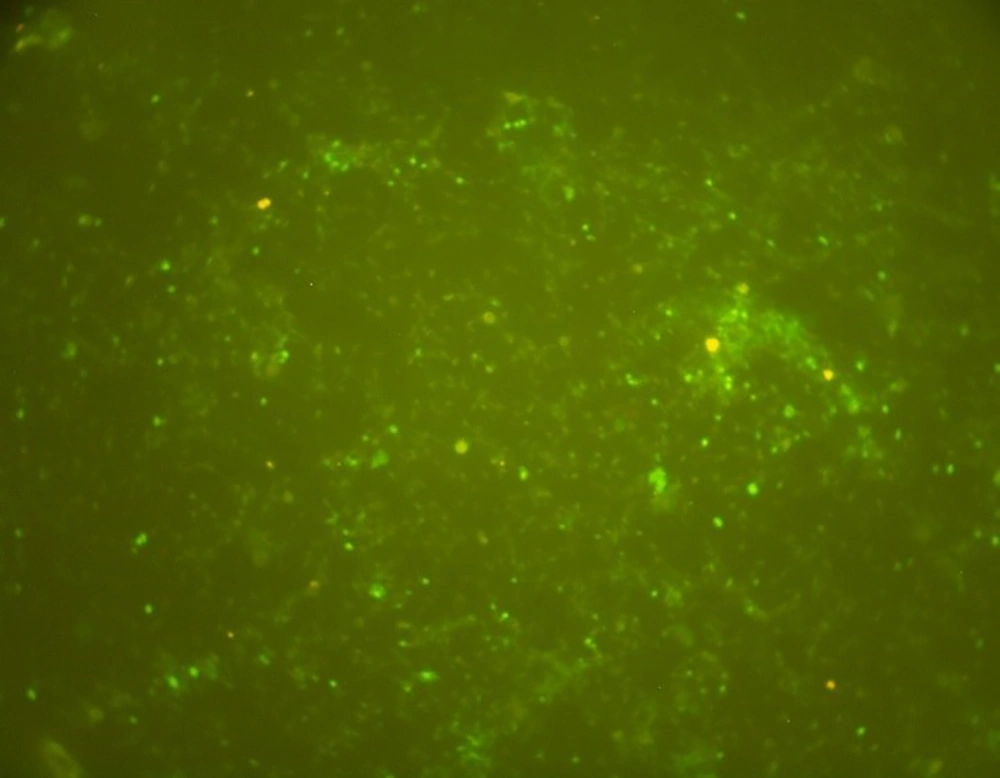

For the evaluation of DNA fragmentation in semen samples of infertile men infected with C. trachomatis, a commercial kit (in situ cell death detection kits, fluorescein, Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was used. Briefly, the semen samples fixed on the slides were washed three times for 5 min with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 containing 0.1% (w/v) sodium citrate for 2 min on ice. Slides were then incubated with a 50-μL TUNEL reaction mixture in a humidified, dark chamber at 37°C for one hour. For positive controls, spermatozoa slides were treated with RNase-free DNase I (400 U/mL, Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) at room temperature for 10 min before incubation with the TUNEL reagent. Positive TUNEL staining was observed under a fluorescence microscope (TE2000U, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using the B-2A filter (450 - 490 nm excitation filter, 505 nm dichroic mirrors, 520 nm bandpass filter). For negative controls, semen slides were incubated with the TUNEL reagent in the absence of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. Samples were washed three times with PBS and coverslips were mounted using a mounting medium (VECTASHELD®, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The sperm TUNEL index was determined by counting the negative and positive stained semen in each of the ten fields of vision (10).

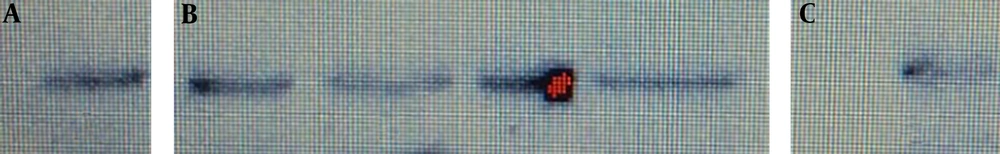

3.6. Western Blot Analysis for Caspase-3 Activity

To assess the caspase-3 activity in semen samples of infertile men infected with C. trachomatis, Western blot was used based on the same methods described in a previous study (11). Briefly, sperm pellet was washed twice with PBS and cell lysate was prepared (1:1) in Quan’s lysis buffer. This comprised lysis buffer (4 mM of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1% NP-40, 20 mM of HEPES, 10 g/mL) and protease inhibitor cocktail (10 g/mL of aprotinin, 1 mM of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 g/mL of trypsin inhibitor, 5 mM of benzamidine). After centrifugation, 30 micrograms of total lysate protein and positive control (Jurkat whole-cell lysate) for caspase-3 were loaded and separated by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE before electrophoretic transfer to nitrocellulose. Blots were incubated with anti-caspase 3 antibodies (1:500) (Abcam, Biotech, Life sciences). Specific antibodies used for these apoptotic markers by Western blot analysis could detect only active forms. After incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500 dilution) (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ), the blot was washed with ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ) and then transferred to X-ray film.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance was assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test and the chi-square test. DNA fragmentation and caspase-3 activation were assessed using t-test. All tests were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

4. Results

In our study, out of 50 endocervical samples from infertile women, U. urealyticum and M. hominis were detected in 25 (50%) and four (8%) specimens by PCR, and 13 (26%) and two (4%) specimens by culture, respectively. In addition, mixed species of U. urealyticum and M. hominis were detected in four (8%) and two (4%) swabs by PCR and culture, respectively. C. trachomatis just was determined by the PCR method in seven (14%) endocervical specimens. The sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 98.9% were obtained for PCR, while they were 52% and 88% for culture, respectively. In the fertile women group, three (6%) cases for U. urealyticum and one (2%) case for M. hominis were positive by PCR. The prevalence of these microorganisms in infertile and fertile women is shown in Table 2. In addition, out of 50 semen samples from infertile men, U. urealyticum and M. hominis were detected in 14 (28%) and 11 (22%) specimens by PCR, and five (10%) and one (2%) specimens by culture, respectively.

| Microorganism | Infertile Women, No. (%) | Fertile Women, No. (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | |||

| U. urealyticum | 13 (26) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| M. hominis | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.495 |

| U. urealyticum and M. hominis | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.495 |

| PCR | |||

| C. trachomatis | 7 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.012 |

| U. urealyticum | 25 (50) | 3 (6) | < 0.001 |

| M. hominis | 4 (8) | 1 (2) | 0.362 |

| U. urealyticum and M. hominis | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.117 |

Chlamydia trachomatis was found in 5 (10%) samples by PCR. Mixed species of U. urealyticum and M. hominis were detected in four (8%) specimens by PCR. Moreover, in the fertile men group, two (4%) cases for U. urealyticum and one (2%) case for M. hominis were positive by PCR. The sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 98.9% were found for PCR while they were 40% and 94% for culture, respectively. The prevalence of these pathogens is shown in Table 3. To confirm the presence of Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma by PCR, sequencing was performed and they were approved on the national center for biotechnology information (NCBI) site and will be recorded soon in GeneBank. The genomic DNA of C. trachomatis with the accession number of KX298123.1 was used as the positive control.

| Microorganism | Infertile Men, No. (%) | Fertile Men, No. (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | |||

| U. urealyticum | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.056 |

| M. hominis | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| PCR | |||

| C. trachomatis | 5 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.056 |

| U. urealyticum | 14 (28) | 2 (4) | 0.002 |

| M. hominis | 11 (22) | 1 (2) | 0.004 |

4.1. Semen Parameters

The semen variables in the infertile and fertile men are shown in Table 4. To assess the effects of the studied microorganisms on semen quality, the semen parameters were compared between infected infertile men and uninfected infertile men (Table 5).

| Variable | Infertile Group | Fertile Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.19 ± 0.8 | 7.18 ± 0.06 | > 0.05 |

| Volume, mL | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | > 0.05 |

| Sperm count, × 106/mL | 53.6 ± 30 | 65.6 ± 5.6 | < 0.001 |

| Progressive motility, % | 27.3 ± 17.4 | 53.5 ± 3.5 | < 0.001 |

| Normal forms, % | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 12.5 ± 1.7 | < 0.001 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

| Variable | C. trachomatis | U. urealyticum | M. hominis | Uninfected | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P Value | Mean ± SD | P Value | Mean ± SD | P Value | Mean ± SD | |

| pH | 7.1 ± 0.09 | 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.09 | 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.01 | 0.5 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| Volume, ML | 3.1 ± 1.5 | 0.6 | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 0.6 | 3.2 ± 1.7 | 0.6 | 3.1 ± 1.5 |

| Sperm count, × 106/ML | 50 ± 38 | 0.7 | 52 ± 38 | 0.8 | 51 ± 38 | 0.7 | 55.4 ± 36.01 |

| Progressive motility, % | 21.1 ± 10.02 | 0.001 | 24.6 ± 14 | 0.01 | 28 ± 12.33 | 0.7 | 28.8 ± 13.6 |

| Normal forms, % | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 0.1 | 4.4 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 | 6.5 ± 1.2 | 0.1 | 6.7 ± 1.8 |

4.2. DNA Fragmentation

The TUNEL assay results are expressed as the percentage of DNA fragmented semen. The results showed that the percentage of sperms with DNA denaturation was increased in infertile men infected with C. trachomatis compared to uninfected infertile men (6 vs. 1.5; P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

4.3. Caspase-3 Activation

Western blot in semen samples of infertile men infected with C. trachomatis showed dense bands compared to uninfected infertile men (level of caspase-3 was higher in infected patients than in uninfected patients; P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

5. Discussion

The exact relevance of C. trachomatis, U. urealyticum, and M. hominis in human infertility is unknown. Some studies have shown that these infections may adversely affect fertility in women and men; however, other studies have failed to show such effects (3, 12, 13). The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence of these microorganisms in infertile couples and the effect of these infections on semen parameters. A number of studies have confirmed that the prevalence of C. trachomatis and genital Mycoplasmas is higher in infertile men than in a fertile group (3, 11, 14). In addition, some studies have isolated these microorganisms more from infertile women than from fertile women (3, 15).

Our study demonstrated a higher detection rate for C. trachomatis, U. urealyticum, and M. hominis in semen samples of infertile men (5 (10%), 14 (28%), and 11 (22%), respectively), as compared to the control group (0 (0%), 2 (4%), and 1 (2%), respectively). The difference in the prevalence of these microorganisms in the case and control groups of men was significant (P = 0.056, P = 0.002, and P = 0.004, respectively). The same was true in swab samples of infertile women (7 (14%), 25 (50%), and 4 (8%), respectively), compared to fertile women (0 (0%), 3 (6%), and 1 (2%), respectively) (P = 0.012, P = 0.001, and P = 0.362, respectively).

The high prevalence of these microorganisms in the study showed that these agents are widespread among infertile men and women, and this is consistent with previous findings in Iran and other countries (3, 11, 14, 15); however, some other studies have demonstrated no difference in the prevalence of these infections between infertile and fertile men (16, 17). Making a definitive conclusion is difficult based on these studies, due to the diversity of the population, the variation in the sensitivity and specificity of the techniques used, the geographical and cultural characteristics of the countries, and multiple sexual partners (5). The main technique for detection of Mycoplasma is culture, but the isolation of these microorganisms is difficult and requires a specific culture medium. PCR can detect many infectious diseases, particularly those caused by microorganisms that are difficult to cultivate (18). In this study, we compared culture with PCR for the detection of genital Mycoplasma. The results showed that PCR is a faster, more sensitive (93%), and easier method than culture, similar to previous studies (18, 19).

In addition to the prevalence of these microorganisms, we evaluated the relationship between these pathogens and sperm quality in men. Previous studies on the effects of these infections on semen showed conflicting results. Some studies have reported a high incidence of Chlamydial, Mycoplasma, and Ureaplasma infections among infertile male and proven the effect of these infections on semen parameters (1, 3, 7). Nevertheless, other studies have shown that there is no relationship between these infections and semen quality (4, 20). Our study showed that C. trachomatis and U. urealyticum were associated with impaired sperm motility and this is compatible with previous studies in our country and other countries (1, 3, 7). The existing differences can be explained by the capability of these bacteria to attach to spermatozoa and their influence on vitality, morphology, motility, and cellular integrity, or host factors and cellular interactions (4).

Variations in sperm parameters and male infertility can be associated with the death of sperm cells induced by apoptosis. Apoptosis is a programmed cell death that results in cell suicide. Caspases play important roles in regulating apoptosis. Sperm cells have been reported to express distinct markers such as activated caspase-3 and DNA fragmentation. There are strong theories that the direct contact of bacteria and their toxins with sperm is an initial signal for stem cell death. In this context, the apoptosis-inducing mechanism of C. trachomatis is best-documented (21). Apoptosis of sperm has been reported following sperm exposure to C. trachomatis both in vivo and in vitro (22). Some studies have shown that the percentage of semen with DNA denaturation was increased in infertile men infected with C. trachomatis compared to uninfected men (5, 23). In addition, other studies have shown that the rate of caspase-3 activation was increased in semen samples of infertile men with C. trachomatis infection compared to uninfected men (5, 24).

Our data demonstrated that the percentage of DNA fragmentation was significantly higher in patients infected with C. trachomatis compared to uninfected infertile men (6 vs. 1.5; P < 0.05). In addition, the level of caspase-3 was higher in infected patients than in uninfected patients, which is consistent with previous findings (5, 23, 24). All of these studies support the role of C. trachomatis in sperm apoptosis induction. The limitations of our study were the low sample size and not respecting the effect of antibiotic therapy in infected patients, which are suggested to be addressed in future studies.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, using the PCR method provides a sensitive measure to detect C. trachomatis and genital Mycoplasmas and is useful for epidemiologic studies of these microorganisms. Our results also demonstrated that these bacterial agents were widespread among infertile couples in Ahvaz (the south of Iran). Chlamydia trachomatis infections could play a role in decreased sperm quality and apoptosis induction. These effects may explain the negative direct impact of these infections on male fertility.