1. Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, aerobic bacillus, flagellated, motile which is the main cause of infection in patients with underlying conditions. It is recognized as a serious opportunistic pathogen. Serious infections due to P. aeruginosa are life-threatening and associated with the highest rates of mortality and morbidity. In recent years, overuse and misuse of antibiotics made this bacterium resistant to broad-spectrum antibiotics from different groups (1, 2). Generally, resistance mechanisms in P. aeruginosato antimicrobial agents can be classified into intrinsic and inherent resistance. In intrinsic resistance, natural or wild cells are resistant to antibiotics through a chromosomal origin. While the inherent resistance is due to gene acquisition such as transposons, plasmids, and integrons by horizontal transfer (1, 3, 4).

Integrons were first described at the 1980s, they are genetic elements. Integrons are a genetic set that are capable of integrating and expressing genes called “gene cassette” and displacing them. All known integrons composed of three key essential components for the procurement of exogenous genes. The int I gene encodes an integron integrase (IntI) (5). This integrase belongs to the family of tyrosine recombinase (phage integrase) integrase protein that catalyzes recombination between incoming gene cassettes. Promoter and the att I (attachment site), which directs transcription of cassette-encoding genes (6).

The most studied integrons are the resistance integrons (RIs) (7). Resistance integrons have been divided into three classes based on differences in the integrase genes, and it seems that each class can acquire the same gene cassettes (8). Class 1 integrons (linkage a Tn 402-like transposon) are widely found in clinical specimens and most antibiotic resistance gene cassettes belong to this class are strongly associated with multiple antibiotic resistance (9). Class 2 integrons are related to Tn7 transposon and associated with resistance to trimethoprim, streptomycin and spectinomycin, while class 3 integrons are rare (10). In recent years, the role of integrons has been identified as a genetic element in the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (11-15). Integrons play a key role in the expression and spread of antibiotic resistance genes (16-18). Therefore, identification of these types of antibiotic resistance genes is essential for successful infection control programs and preventing the spread of resistant strains.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the antibiotic resistance pattern and the prevalence of integron class 1 (int1) and 2 integrons (int2) in P. aeruginosa strains isolated from hospitalized patients in Markazi Province, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 100 non-duplicate isolates of P. aeruginosa were obtained from hospitalized patients in Markazi Province, Iran. The following standard conventional biochemical tests were used for the identification of all isolates: catalase and oxidase tests, growth at 42°C, pigment production on Mueller-Hinton agar, Oxidative/fermentation glucose test (OF glucose test).

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

The Kirby-Bauer’s disk antimicrobial diffusion test on Mueller-Hinton agar (Merck, Germany) in accordance with the guidelines of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute were used in order to evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility of P. aeruginosa isolates (8). Six antibiotics (MAST, UK) were employed in the study, including ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 µg), cefotaxime (CTX, 30 µg), gentamicin (GEN, 10 µg), sulfamethoxazole /trimethoprim (SXT, 25 µg), imipenem (IPM, 10 µg) and piperacillin/tazobactam (PTZ, 100 µg/10 µg). For quality control of the tests, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used as standard microorganism.

3.3. Molecular Analysis

The DNA of all the isolates was extracted from the bacterial cells by boiling method. In brief, few colonies of overnight culture of P. aeruginosa suspended in 1 mL distilled water. Then boiling for 15 min and centrifugation. The supernatant was stored at -20°C. Moreover, PCR was carried out using a specific primer for detection of class 1 and 2 integrons. To this aim, PCR mixture contained DNA template 2 µL, Mastermix 12.5 µL (Yekta Tajhiz Azma, Iran), distilled water 8.5 µL and each primer 1 µL (Gene Fanavaran, Iran) in a final volume of 25 µL. The primers used in the amplification reactions were as follows (Table 1). PCR experiments for Int1 and Int2 genes were performed (thermocycler: PEQLAB, UK) with 35 cycles consisting of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30s of annealing at 55°C and 30 s extension at 72°C. Finally, PCR products were run on 1.5% agarose gel (w/v) (Merck, Germany) with DNA Ladder 100 bp (CinnaGen, Iran) for 40 min at a constant 80 V using 1X TBE buffer.

| Gene | Nucleotide Sequence (5’ to 3’) | Amplicon Size, bp | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Int1 | F: CAG TGG ACA TAA GCC TGT TC | 160 | (19) |

| R: CCC GAG GCA TAG ACT GTA | |||

| Int2 | F: TTG CGA GTA TCC ATA ACC TG | 288 | |

| R: TTA CCT GCA CTG GAT TAA GC |

Sequences of Primers Used in PCR

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The SPSS software (IBM Corp., USA) version 21.0 was used for statistical analysis. A P value of > 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

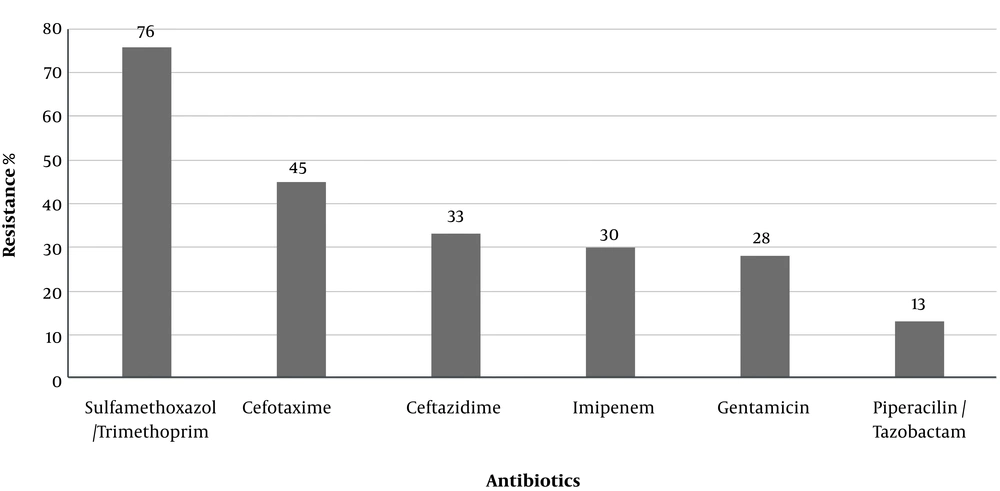

A total of 100 isolates of P. aeruginosa were collected from hospitalized patients in Markazi Province, Iran. Susceptibility patterns against the tested antibiotics are shown in Figure 1. The most prevalent antibiotic resistance included trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (76%) and cefotaxime (45%).

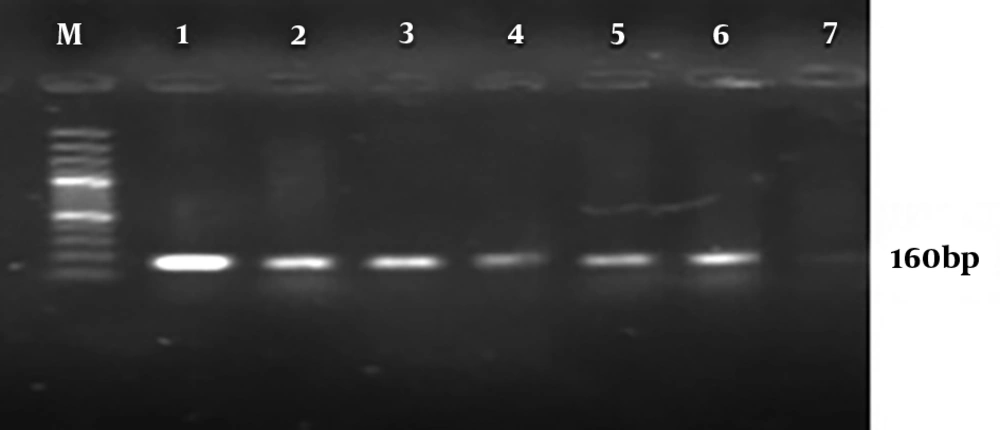

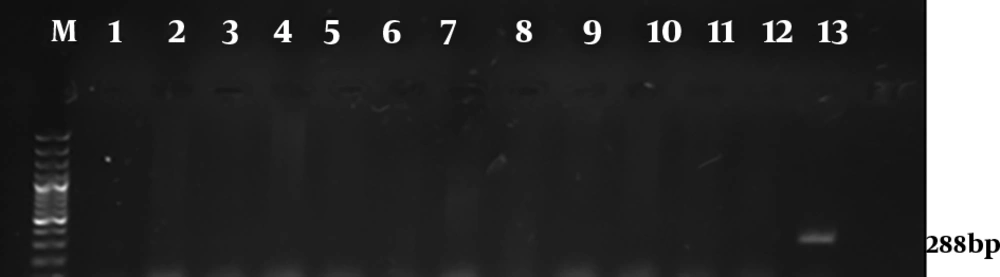

Molecular analysis for the presence of class 1 and 2 integrons showed that 95% P. aeruginosa isolates harbored the int1 gene (Figure 2), but none of them demonstrated the int2 genes (Figure 3). The results of chi-square analysis showed a significant association between the presence of class 1 integron and resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and cefotaxime. There was no significant association between resistances to other antibiotic resistance with the presence of class 1 integron (Table 2).

| Antibiotics | Integron-Positive Isolates (N = 95) | Integron-Negative Isolates (N = 5) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | ||

| IPM | 65 (68.42) | 2 (21.05) | 28 (29.47) | 3 (60) | 0 | 2 (40) | 0.848 |

| SXT | 13 (13.68) | 8 (8.42) | 74 (77.9) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 0.021 |

| CTX | 8 (8.42) | 45 (47.37) | 42 (44.21) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 3 (60) | 0.018 |

| GEN | 67 (70.52) | 2 (2.1) | 26 (27.36) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 0.798 |

| PTZ | 65 (68.42) | 17 (17.91) | 13 (13.68) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.324 |

| CAZ | 63 (66.31) | 0 (0) | 32 (33.68) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 0.231 |

The Correlation between Presence of Class 1 Integrons and Antibiotic Resistancea

5. Discussion

The genus Pseudomonas contains more than 140 species in which P. aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that causes severe acute and chronic infections (20, 21). In recent years, overuse of antibiotics leads to a significantly increased bacterial resistance to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a growing concern for the public’s health (2, 22). The presence of mobile genetic elements (Integrons) can be regarded as one of the most important factors for the occurrence and transmission of bacterial resistance. The present study investigated antimicrobial resistance profile and prevalence of class 1 and 2 integron resistance gene cassettes in P. aeruginosa strains isolated from hospitalized patients in Markazi Province, Iran.

Based on the results of this study, the highest resistance level was observed in our study to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (76%). Drug resistance has been vigorously studied in P. aeruginosa strains isolated from clinical specimens, several of these studies are discussed here. Similar investigations were conducted in many parts of Iran for resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole of P. aeruginosa that ranged from 57/58% to 96/4% (23-25). This study showed that gentamicin and imipenem were effective antibiotics for P. aeruginosa so that only 28% and 30% isolates were resistant to gentamicin and imipenem, respectively. Reports on Iran show that the resistance rates to gentamicin and imipenem are as follows: Arak 24% and 23%, Zanjan 55.1% and 63.8%, Yazd 63.2% and 62.5%, Tabriz 62% and 46.5% (26-29), respectively. Results of these studies were variable since it depended upon the times or places that the pertinent studies were performed.

In this study, class 1 integron of P. aeruginosa isolates was detected in 95% of isolates and class 2 integron was not found. The frequency of different classes of integrons was investigated in published Iranian studies from different regions of Iran. In a study that was conducted in 2015 by Hosseini Pour et al. (30), 92% and 52% of strains had class 1 and 2 integrons, respectively. In the study conducted by Khosravi et al. (31) in 2017, the prevalence of class 1 and 2 integrons was evaluated among 93 P. aeruginosa burn isolates. Their results showed that class 1 integron was detected in 95.7% of isolates, while none of them harbourd class 2 integron (31). These studies, have similar results to our study. But the results of the following studies differed from our study results. In 2018 Ebrahimpour et al. (29) reported that 30% of P. aeruginosa isolates carried class 1 integrons.

In a study conducted by Yousefi et al. (32) in 2010, class 1 integron was detected in 56.3% of the isolates. In a study by Khorramrooz et al. (33), class 1 integron was detected in 35.6% of isolates, whereas class 2 integron was not found. The frequency of class 1 integron in other parts of the world, in previous studies in Nigeria and Brazil, was reported 57%, 41.5%, respectively (34, 35). In a study by Xu et al. (36) in China in 2009, 45.8% and 19.5% of isolates had class 1 and 2 integrons, respectively.

The results of this study, in comparison to similar studies, showed a high prevalence of class 1 integron isolated. The reason for the difference in reported percentages in various studies can be due to differences in geographical location, bacteria strains, overuse and misuse of antibiotics. It should be noted that in the present study, a significant correlation was observed between class 1 integrons and resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and cefotaxime, which could be the reason for the presence of resistance genes to these drugs in this class of integrons. In cases that there was no significant correlation between these genes and other antibiotic resistance, the resulting resistance can be achieved through other ways such as the presence of the resistance genes in resistance plasmids, etc.

5.1. Conclusions

The high presence of class 1 integron in this study and since the integrons are mobile genetic elements and they can transfer between the various species of bacteria involved in Hospital infections, using effective infection control activity and appropriate therapies are necessary to prevent dissemination of them. It is recommended to conduct more detailed studies on the nature of integrons and other resistance mechanisms in these species to provide better therapeutic and control strategies in the future.